Just before sunrise on March 1 a band of Hutu rebels descended on Buhoma, a tourist village at the northwest edge of Uganda's Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. They opened fire with automatic rifles and grenades, killing a game warden and three park rangers, setting buildings and vehicles on fire, and taking 31 foreign tourists hostage.

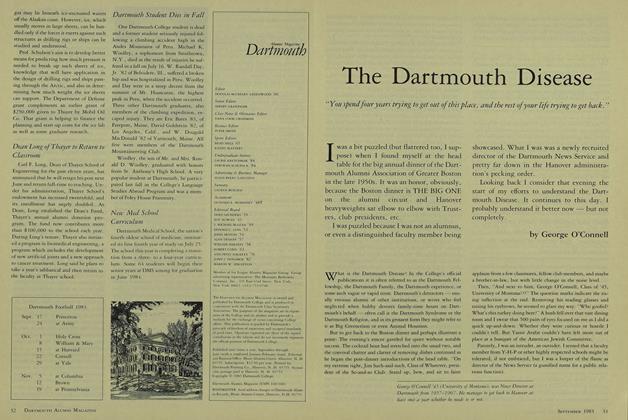

The tourists had come to Bwindi to see the endangered mountain gorilla. With violence and political instability in neighboring Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda had been considered the last place in the world safe for viewing the rare subspecies and Bwindi, a national park since 1991, was Uganda's jewel. Of the 600 mountain gorillas believed to be in existence, half live in Bwindi.

The rebels, who call themselves the Interahamwe ("Those who kill together"), are remnants of the army that murdered more than half a million Rwandans in 1994. They had reportedly regrouped in the jungles of the Congo. Bandit and rebel violence had spread across the borders into Uganda, but before March 1 it hadn't surfaced in Bwindi, even though the Congolese border is less than an hour's walk from the park entrance.

The rebels herded the tourists into a part of the encampment reserved for Abercrombie and Kent, an upscale tour group. Apparently singling out the English-speakers, the rebels marched 16 of the foreigners into the forest. And there, in the national park whose name means "place of darkness," the rebels bludgeoned and macheted eight of them to death.

The brutal killings shocked the world and made international news. To a small group of researchers and others concerned with the endangered gorillas, the tragedy held implications beyond the headlines.

A LITTLE OVER A YEAR AGO I spent two months in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest with Professor Michele Goldsmith, a postdoctoral teaching fellow in Dartmouth's anthropology department. Professor Goldsmith had earned her doctorate studying western lowland gorillas in the Central African Republic. She had come to Bwindi to study the dietary and behavioral ecology of mountain gorillas (Gorillagorilla beringei) and chimpanzees {Pan troglodytes scheinivurthii). During an off-term I assisted her with her research. From mid-December to February we recorded gorilla behavior, mapped gorilla nest sites, and collected and analyzed dung samples. Our research continued the work Professor Goldsmith had started the year before. Bwindi is the only place in Africa where mountain gorillas and chimpanzees are sympatric where they live together. She was testing the hypothesis that this co-habitation would result in behaviors that were measurably different from either species living alone. This was the only noncaptive research being conducted on the relationship between these two elusive apes.

The region's volatility became apparent early in our trip. On Christmas night bandits raided the park's management center, where Professor Goldsmith and I were sleeping. Sweating, I lay flat on my back as footsteps sped past the window of our hut and bullets from Kalashnikov AK-47s scattered the dead leaves of the trees outside our hut. For two and a half hours gunfire rang out in the darkness. The sky flashed with light over the border toward Rwanda. I wondered if it was war or lightning.

The next morning a park guard informed us that the intruders had been not rebels, but vandals from the Congo who had come to steal a motorcycle. In light of the recent killings I wonder if that was true.

Five days after the raid, we moved our base camp to a lower elevation on the western edge of the forest near Buhoma. Our new camp, overlooking the brown, swollen Kashasha River, was more remote and, I hoped, safer. The danger in and around the park, we'd been told, was likely to come from armed thieves, not the warring factions just over Uganda's border. It was doubtful that we'd encounter thieves here, a five-hour hike in from Buhoma.

Amid the unrelenting rain and humidity, I collected data from this lower elevation, which we compared to our findings higher in the forest, where there are fewer chimpanzees and less available fruit for gorillas. I mapped nest sites, looking for clues that proximity to chimpanzees was affecting gorilla nesting patterns. Gorillas, like all great apes, build nests each night. All adults and juveniles within the group build their own nests, and group members generally nest within the same area. Although gorillas, for years, were believed to be terrestrial quadrupeds, gorillas in Bwindi nest in trees as well as on the ground. One nest site was typical: Around four meters up, where a monstrous acacia tree stretched in yoga-like posture, twigs and leaves were matted into a concave nest some two meters across. An older nest lay tangled in dry leaves near the first. In the dense vegetation the nests are almost impossible to see.

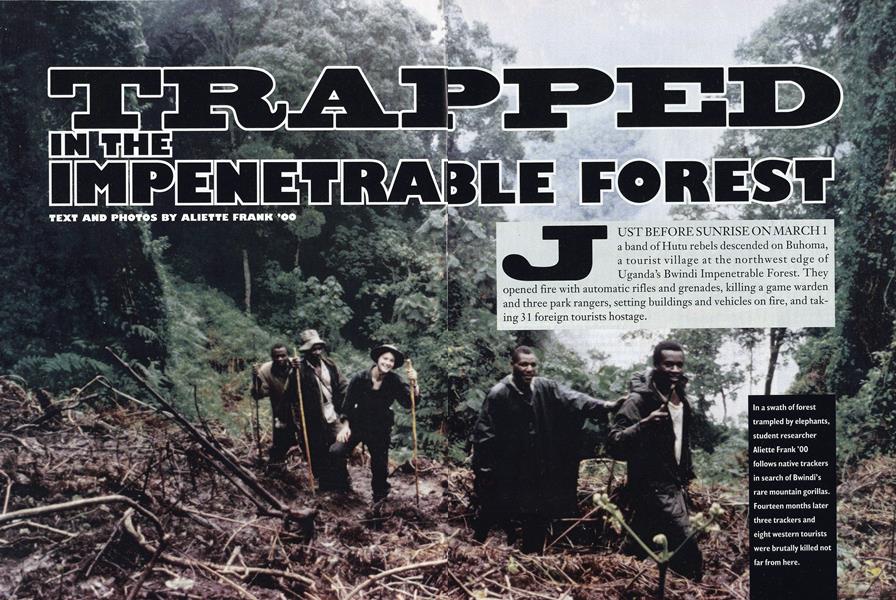

Native Ugandans employed by the park served as our trackers. Typically, when I followed the trackers, I tried to keep them between me, the nests, and the gorillas. Occasionally, though, a gorilla appeared behind or to the side of me. Four-hundred-pound silverbacks, whose heads were five times the size of mine, chastised me. One silverback in a group the alpha male is likely to make a charge when people approach, giving the female gorillas and the young time to flee. I learned from the trackers how to react. Hold your ground. Don't run. Avoid eye contact. Keepbreathing. Don't faint. On one occasion two silverbacks howled, leapt, spun, and roared toward me with piercing shrieks. I froze, averted my eyes, and prayed. The shrieks and the charge ended with a bluff not five meters from me. One of the silverbacks beat his chest and gave the soggy ground a tremendous whap with his open hand. A one-year-old launched himself onto a pile of leaf rubble and watched. Puckering his lips, the shaggy youngster batted a wrist-thick stalk of ebikwa and sat pretending to feed on the wild celery. He glanced back at the silverback. My hands faltered with the lens of the camera I was trying to keep hidden. This group of gorillas has been poached in the past, the trackers had told me, and they might mistake a camera lens for the barrel of a gun. The infant shambled on his knuckles toward me. About three meters away he coughed a warning which seemed half-aggressive, half-curious. He paused and looked at me with shining, umber eyes. I returned the gaze, a mistake: looking in the eye of a gorilla is a sign of aggression. He turned and disappeared.

THE GORILLA GROUPS WE STUDIED in the low elevations were classified as "tourist groups." These apes were in the process of being habituated to human contact but were still too aggressive to be viewed by the 5,000 yearly tourists in Bwindi. At that time, just two gorilla groups had been fully habituated to tourists.

Habituation is a key part of the plan to protect the gorillas here. The Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is a surprisingly small island of trees covering just 331 square kilometers. The park contains a series of steep hills rising to 8,000 feet, covered in centuryold trees. In sharp contrast, Bwindi is surrounded abruptly by open, cultivated land in one of Africa's most densely populated regions. The park was modeled on the success of a 1978 project that established gorilla tourism in Rwanda. The goal is to protect the gorillas and their habitat by drawing a link between the forest and the welfare of the people living around the park. Tourism creates jobs for local citizens. Ten percent of the tourism proceeds in Bwindi are targeted for education, small development programs, and gorilla conservation. Ironically, though, habituating gorillas to humans may actually be decreasing the gorillas' chance of survival. As the tourism program expands, the gorillas are losing their natural fear of humans. "Fear," Professor Goldsmith explained to me, "was the only thing keeping them in the forest." And staying in the forest meant safety.

Over the past couple of years the gorillas have increasingly slept outside park boundaries on plantations, smashing banana trees to eat the pith, and growing more fearless of humans. The risk of poaching, always a danger, has in creased creased as a result. The increased human contact has created another worry, too. Human-borne diseases have been diagnosed in gorillas, likely transferred from neighboring farmers who have been using the edge of their cropland as a latrine.

This coexistence poses a classic environmental dilemma: a growing local population requires cropland for subsistence, but the survival of the gorillas and their habitat provides opportunity for badly needed revenue. "Their survival or demise is our survival or demise," says Debby Cox of the Jane Goodall Institute. During the time I was there, flooding and cholera pushed the subsistence farmers near Bwindi even closer to the edge of starvation, heightening the tensions between locals and park officials. The tensions complicate an already fundamental challenge: the park lacks resources of many kinds money, staff, equipment, expertise. Uganda as a whole lacks the infrastructure for even basic health and education programs. And now the Rwandan conflict between the ethnic Hutu majority and the ethnic Tutsi minority has spread to attacks on tourists.

Much of the reporting in the United States following the recent tragedy in Bwindi focused on the political motives of the Hutu rebels, who oppose American and British support of Uganda's military and anyone else perceived to be sympathetic toward the Tutsi. "The rebels that came to Bwindi were familiar with tourism," says Norm Rosen, an anthropology professor at Cal State-Fullerton who has helped coordinate conferences on the mountain gorillas. "They knew how to affect Uganda's pocketbook. etbook." Seventy percent of the Uganda Wildlife Authority's revenue came through Buhoma. Because mountain gorillas have been considered the flagship species for tourism in the region, all Ugandan park pocketbooks, as well as those in other central African countries, will no doubt be affected.

"The rebels threatened that if Westerners ever came back, they wouldn't bother taking hostages. They would just kill them," Elizabeth Garland, an American student who escaped the massacre, said in an interview with National Public Radio. Following the massacre, the U.S. State Department issued a warning against all travel in western Uganda. Tour companies, including Abercrombie and Kent, suspended their Bwindi trips until further notice. Apparently, though, not everyone was taking the danger seriously; much to park personnel amazement, tour operators in Kampala reported that tourists were asking for canceled gorilla permits three days after the massacre.

Was the massacre really a complete surprise? "The barbarism of the Interahamwe is nothing new to Rwandans," says Liz Williamson, director of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund in Rwanda. British papers claimed that the rebels had warned the Ugandan government of an attack, but the government had remained silent, fearing the news would harm its tourism industry. A conversation I'd had with Rutaro, a local Ugandan tracker I worked with in Bwindi, has come back to haunt me. "When you are back home you will hear, 'The rebels are in Buhoma,'" Rutaro had told me.

"What will they do when they come?" I'd asked.

"They will cut our heads and kill us. You think they will come with their guns and leave us? No We will fight them with machetes and arrows and spears, and we will throw rocks. Ha ha! We have no weapons. We can only run and hide in the forest."

As Rutaro spoke he'd motioned to the forested hills in the distance, where hundreds, perhaps thousands of rebels now stalk and are being stalked by the Ugandan militia. Beyond Rutaro, rows of sweet potatoes and beans, staple Ugandan crops, streamed along the terraced hillsides. "But then," he said, "we will die of starving."

Starvation, even in normal years, is a constant threat in this poverty-stricken region. During my time in Bwindi, I tasted hunger, too. In early January Professor Goldsmith hiked out of the forest and made the 12-hour drive to Kampala, where she was dropping off a Ph.D. student at the university. We had decided it would be safer for me to remain in the forest and continue our research, away from the accident-prone Ugandan roads. I'd continue to follow the gorillas with the trackers employed by the park. Professor Goldsmith planned to return about five days later with food.

The trackers, hired to stay with me, ended up periodically leaving, either returning drank or not at all. I grew afraid, hungry, and sick as the days stretched past a week and there was still no word from Professor Goldsmith. I didn't dare hike out of the forest. I'd heard reports of cholera and dysentery outbreaks in Buhoma, and that the markets there were selling no food. I thought of the word Nyirmachabelli, "Woman who lives alone in the forest." It is the epitaph on the gravestone of Dian Fossey, the author of Gorillas in the Mist who was killed by poachers just south of here in Karisoke, Rwanda.

For days my eyes were glued to the horizon. Two weeks after her departure, Professor Goldsmith's figure finally appeared across the dark corduroy mounds of potato fields. Flooding and landslides had delayed her return from Kampala and had blocked the roads into Buhoma.

We left Uganda a month early. At least we had the luxury of being able to leave. The people of Bwindi are still there. Just two days after this year's massacre, reports from Buhoma said the village had no food.

Buhoma and the neighboring communities are only memories to me. Now they are only sparks in the memory of the people there as well. Inside the Abercrombie and Kent tents in Buhoma, I had mulled over words that Grant Anderson, the manager of the camp, told me, "In Africa, things just happen. If not today, then tomorrow." The Hutu rebels had set these tents aflame. Paul Wagaba. the warden with whom we worked, was killed and burned. According to early reports, rebels looted and burned the village buildings, burned villagers, and left jobless everyone who survived, including those who tracked, monitored, and protected the gorillas. Buhoma's entire infrastructure will have to be rebuilt, as will the confidence of the local people. "Basically, this one morning, all the prospects, hopes, and aspirations that were built up by tourism...all the things that structured hope in these people's lives, have disappeared," said Elizabeth Garland, the student who escaped the massacre.

Loss and the need to rebuild are not new to this generation of Ugandans. The country has made a remarkable resurgence since the dark days of Idi Amin and his successors in the 1970s and early 1980s. The people of Uganda have shown resiliency and the willingness to balance short - and long-term needs. But what about the gorillas? "Without the park or support of the local population, the forest and the gorillas would probably last less than five years," says Ted Dardani '84, who worked with the World Wildlife Fund to help establish conservation programs and construct buildings in Bwindi. "It's up to us," he says. "And 'we' is not just the white mzungus and colonialists. It is the local people as well. It's all in all our hands."

The research being done by Professor Goldsmith and others has ground to halt. Park officials project at least six to 12 months before research or tourism resumes.

The uncertainty about the future is just a part of working in Africa, Professor Goldsmith said to me once. "C'estI' Afrique." But I can't stop thinking about that brief interaction I had with the infant gorilla, when our eyes met. "So what will I tell my grandchildren, or even my children for that matter, about you?" I ask him in my mind. "Will you have a future?" The young gorilla is silent. He does not have an answer. Neither, it seems does anyone else.

In a swath of forest trampled by elephants, student researcher Aliette Frank '00 follows native trackers in search of Bwindi's rare mountain gorillas. Fourteen months later three trackers and eight western tourists were brutally killed not far from here.

Gorillas normally eatjust vegetation andberries. This young200-pound female hastaken to stripping treebark, behavior that hasput the apes at oddswith local bananafarmers. It was hopedthat sightings such asthis would bring hardcurrency from tourismto an impoverishedregion providing jobsfor the locals and fundsfor preserving thegorillas' habitat.

Far from the areasopen to tourists, Franksets her camera onself-timer to captureherself drinking a"camp cocktail," abowl of boiled water.Some of her workinvolved habituatingwild gorillas for regularcontact with humans.During part of her stay,Frank, like famed researcher Dian Fossey,was Nyirmachabelli, a"woman who livesalone in the forest."

Before the rebels' attack, tuxedoed bellhops and spacious canvas tents offered upscale tourists an incongruous entree to the Impenetrable Forest.

With tourists in mind,park managers openeda view of the Virungamountains along theRwanda-Congo border.Regional warfare hasclouded a key question:Will tourism save theBwindi gorillas orcontribute to theirextinction?

ALIETTE FRANK is currently turning her journal entries from the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest into a book.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHue and Cry at the Whitney

May 1999 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Feature

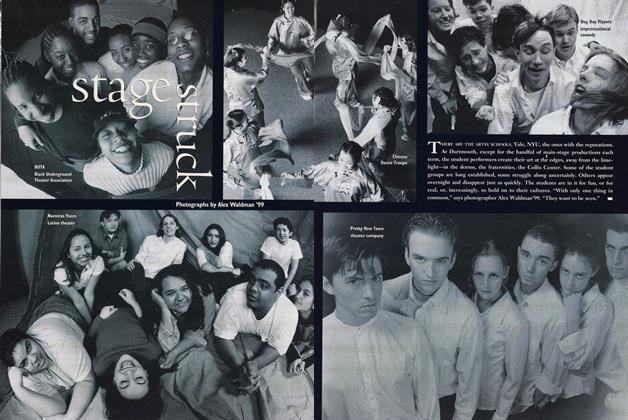

FeatureStage Struck

May 1999 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

May 1999 By Don O'Neill -

Article

ArticleThe Financing Game

May 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe Masculine Mystique

May 1999 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleWhat History Can and Cannot Teach

May 1999 By James Wright

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Institute

MAY 1971 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO IMPROVE YOUR VISION NATURALLY

Sept/Oct 2001 By GLEN SWARTWOUT '78 -

Feature

FeatureGOTHAM GAMBIT:

December 1956 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Cover Story

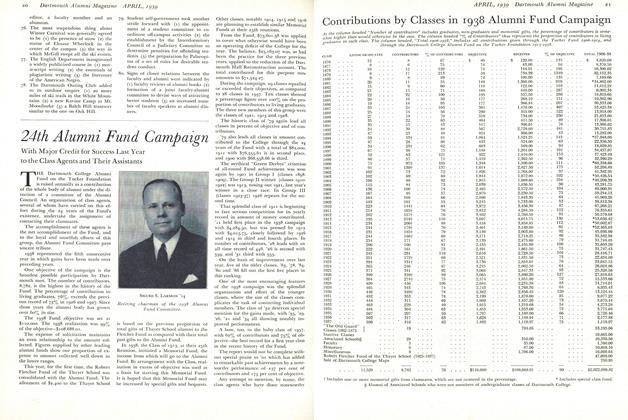

Cover Story24th Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1939 By Luther S. Oakes '99, Edward K. Robinson '04, Fletcher R. Andrews '16, 2 more ... -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

DECEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham