Could colleges learn from car dealers?

WHAT IF YOU were buying a new car, and like most Americans paying for it gradually? Nothing down, let's say, and then 36 monthly payments.

What if the first 12 payments were each $399, but when the second year began the dealer sent you a notice? He was increasing your monthly payments to $419. Blame inflation, he explains.

What if he didn't stop there? At the beginning of the third year he informs you that you are now to start paying $435. In the same letter he proudly points out that you are getting a bargain. The first increase had been five percent. This one was only four percent.

So far as I know, no car dealer has ever done that kind of financing. Colleges, on the other hand, do it all the time.

Certainly Dartmouth does. The parents of a current Dartmouth senior, if they are paying full tuition, spent $20,805 for their son's or daughter's freshman year. (I'm ignoring room rent, food, etc.) Sophomore year was a little more expensive. Then they paid $21,846 in tuition. That's an extra $1,041, just over five percent. Junior year was almost identical. They paid $22,896, up another $1,050, another five percent. Finally, the proud senior, graduating next month. Here they got a modest bargain. Tuition went up only to $23,790,arise 0f$894, only four percent.

These hikes are not enormous; anyone who can afford full Ivy League tuition can probably squeeze out a few thousand more. (In the case of '99 parents, $6,117 more.) Psychologically, though, I think it's a terrible plan. Up, up, always up. A good thing this isn't Poland, where college lasts five years.

It's not as if there were no choice. There are several. Some colleges offer parents the option of paying for the whole thing in advance. Just look at the first-year tuition bill and mail in a check for four times that amount. You escape all future increases.

Dartmouth offers this option, as do Harvard, Brown, and about 110 other colleges. Oddly enough, it's not very popular, at least here. Only 20 of the more than 2,000 fulltuition students at the College have been prepaid. The size of that first check may have something to do with it. The parents of a '99 who elected to prepay would have had to send off a check for $83,220. And the parents of an '02 would make it out for $95,160. It may be that a lump sum that big is hard for most people to swallow.

There is another option much rarer, and to my mind, a lot more interesting. It's usually called "guaranteed tuition," and various forms of it are available at about 30 of the roughly 1,700 American colleges and universities.

The basic idea is very simple. Whatever the tuition happens to be when a first-year student arrives, the college promises to keep it at that figure until he or she graduates. A few colleges make this promise to the whole freshman class; more commonly some freshmen join the plan and others don't.

Take Baylor University in Texas. Here it's an option much like getting an extended warranty with a car. You pay extra. This year at Baylor most freshman paid $308 per credit hour; next year they will pay more. A minority, however, paid $349 per credit hour, and they will still be paying $349 when they are seniors. If Baylor meanwhile makes big increases in tuition, those pay-ahead freshmen will come out ahead. If it raises tuition slowly, they will at best break even. They could even lose. "Basically, it's a hedge against inflation," says Donna McGinn, director of student account services at Baylor.

Another mode is more dramatic and daring. The whole entering class gets the guarantee. Tuition goes up yearly, just as it does at every college.* But only the new freshmen get the new bills. The sophomores, juniors, and seniors go right on paying what they did when they were freshmen. It makes a neat reversal of the up-up-up system.

None of these tuition plans is wildly popular. As I mentioned, Dartmouth has only 20 pre-payers. Baylor finds that just about one percent of its students elect guaranteed tuition. McMurry University, also in Texas, is having second thoughts about its guarantee system.

But wait a minute before you conclude I'm talking foolishness. I haven't told you yet about Huntington College in Indiana. Like Baylor, Huntington offers guaranteed tuition as an option. Unlike Baylor, it gets a huge response. Forty-five percent of Huntington's students have elected it and they do not start out with a special high rate in order to elect it. Freshman year they pay die same tuition as the 55 percent not on the plan. Starting sophomore year, they of course are paying less, since the 55 percent will all have had a tuition hike.

What's the catch? I can't see that there is a catch, except for a one-time fee equal to ten percent of that year's tuition.

And that's it. Level tuition thereafter. According to John Paff, the college's director of public relations, the family of a '99 who joined the plan saved $2,465 in tuition, about two and a half times the entrance fee. And they had the pleasure of level tuition.

I'm not thinking that we should immediately try the plan here. I'm perfectly aware that any money parents save on tuition, the College will have to find somewhere else. What I am thinking is this. It seems as if colleges and universities ought to be able to do as well as car dealers in pricing our product.

Between 98 and 99 percent of colleges raisedtuition this year. Who didn't? The nine campusesof the University of California didn't. They reduced tuition (by a not-very impressive $91).The five UMass campuses also didn't. Over thepast three years they have cut in-state tuition by$242. The striking case is Marlboro College inVermont. Marlboro's tuition thisyear is $20,300. Next year it will be $18,800, down a cool $1,500.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

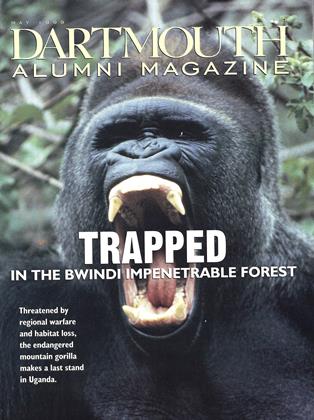

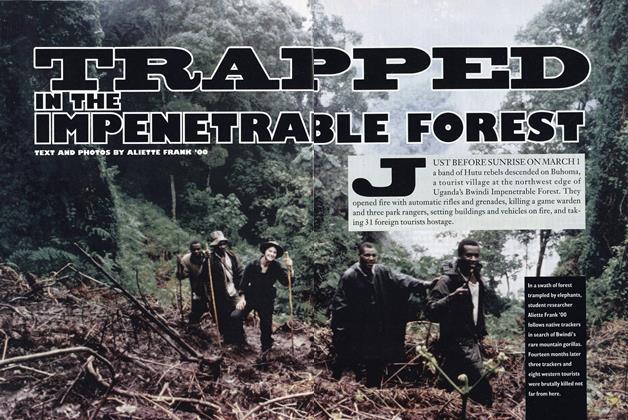

Cover StoryTrapped in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

May 1999 By ALIETTE FRANK '00 -

Feature

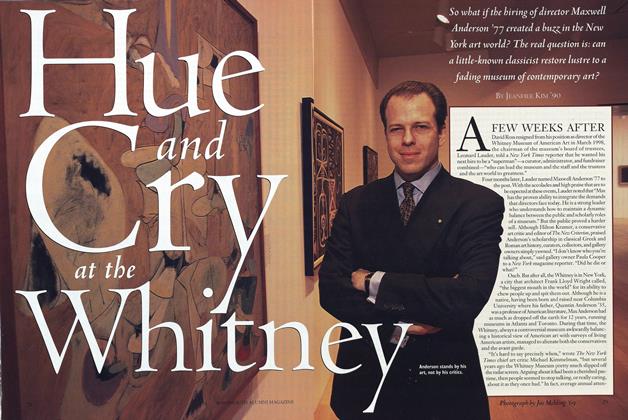

FeatureHue and Cry at the Whitney

May 1999 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Feature

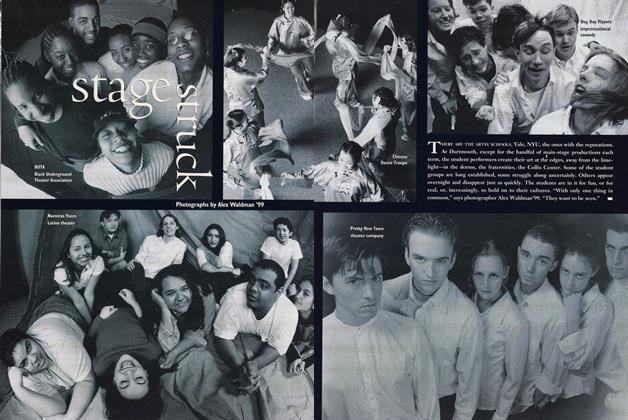

FeatureStage Struck

May 1999 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

May 1999 By Don O'Neill -

Article

ArticleThe Masculine Mystique

May 1999 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleWhat History Can and Cannot Teach

May 1999 By James Wright

Noel Perrin

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

MARCH 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThe College in the Suburb

May 1974 By NOEL PERRIN -

Books

BooksWhich Came First?

March 1976 By NOEL PERRIN -

Cover Story

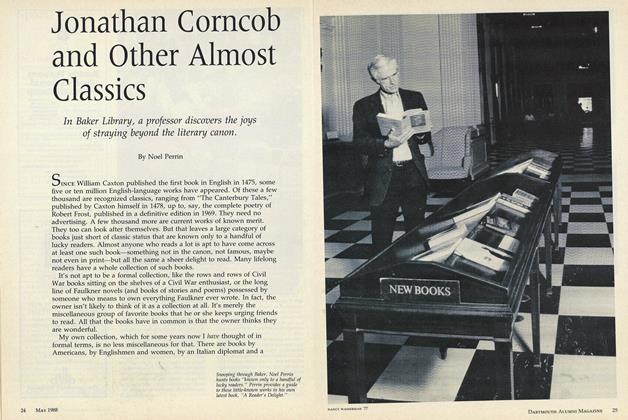

Cover StoryJonathan Corncob and Other Almost Classics

MAY • 1988 By Noel Perrin -

Sports

SportsThe College's First Fan Picks a Winner

December 1989 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleArtists 22, Philistines 14

OCTOBER 1999 By Noel Perrin