Seventy years ago Bravig Imbs '27 shook the campus with hisprovocative novel, The Professor's Wife. What happened to the authorafter that was the stuff of darker fiction.

JANE RAMSON STILL LIVES IN HANOVER at the age of 90- something, having been in the town virtually all her life. But don't try to find her in the phonebook, because Ramson isn't her real name. It was the name given her by Bravig Imbs (which was only partly his real name) in the notorious novel that rattled the cages of just about everyone in town back in 1928. The book was called The Professor's Wife and neither of the two bookstores that Hanover boasted back then would carry the thinly disguised study of Dartmouth life. But banning it didn't prevent just about everybody from getting a copy.

Of course, the administration at the time this was President Hopkins's era denied that there was any official embargo and claimed it was the merchants' own choice. That's what Parkhurst told the Boston papers. Yes, word leaked out of Hanover that there was a hot book at large.

Let's accept the official denial. After all, the college in the book wasn't called Dartmouth. In fact, it wasn't called anything. And the college president was named Heron, not Hopkins. The names of everyone in the book from Heron to Jane Ramson to her family dog did, however, inspire what virtually became a cottage industry in Hanover at the time: drawing up who's-who keys.

Studious types at Sanborn and Baker would, of course, call The Professor's Wife a roman a clef (rhymes with fray), and everybody in it is supposed to be somebody. Back in 1929 this magazine reported that "the lampoons are obvious." That's why Bravig Imbs, of the class of 1927, and only 24 when the book was published, got banned in Hanover. And that's why—out of respect for the real Jane Ramson we're not going to reveal her identity as we tell the strange tale of Bravig Imbs, a minor star in Dartmouth's firmament.

Imbs is gone and so are all the characters except Jane Ramson. The book has been out of print for decades. There's a copy under lock and key along with the keys in the College's archives, but the copy in the stacks was stolen a long time ago. There are probably a few copies around Hanover, hidden on shelves behind more important books. Perhaps a copy will even turn up someday in Jane Ramson's estate. She was, after all, The Professor's Wife's daughter.

The jacket blurb called it "a novel that mingles real and imaginary characters in brilliant and provoking fashion." Most people in Hanover bought, at least, the "provoking." A contemporary news clipping from the Boston Transcript, under the headline "Dartmouth Man's Book Is Banned in Hanover," called it a lampoon of the family of a prominent Dartmouth professor. One review said: "This extraordinary novel, with its mingling of real and imaginary characters, will surely lead to much talk and conjecture." Well, they got that right. The old files in the new Rauner Special Collections contain no less than three different keys, mostly written by real professors, keys that match Imbs's imaginary characters with real-life professors and townspeople. One keyster even identified the fictional professor's wife's dog Scarot as the real-life Hanover pooch Chicot, "a horrible little dog." All this, despite the fact that right there in the front of the book it says:

NOTEThe scene of this story is any Americancollege town, and the characters, aside fromcelebrities who are called by their actual names,are all fictional creations.

Now, this book report doesn't purport to be a literary critique. Maybe you'll read the book if you can find a copy and judge it for yourself, by today's standards. Most readers today won't recognize anyone. I didn't, although I did study with a couple of the alleged players back in the 1940s when nobody talked about the book, at least in public. Don't expect dirt in TheProfessor's Wife. Don't expect sex, or even heavy breathing. Nobody says a four-letter word. This is a character study of a genuine character, the professor's wife. Okay, so she hated the book, but you won't. It's amusing, and it tells you a lot about those post-Victorian times.

Along with several real-life contemporaries such as Robert Frost and Rebecca West, there are at least 50 characters in the book, major and minor, representing a cross-section of College departments. There's little doubt but that the most interesting character of all was the real life author who's in the book as its fictional narrator. When he enrolled at Dartmouth with the class of 1927 it was as Wilbur Eugene Imbs. But within a couple of years he had a nom de plume: Bravig Imbs. Somebody said "bravig" is Norwegian for broad bay, but it wasn't a Norwegian who said it. Anyway, that's what he was called when, years later, his obituary appeared in Time magazine a full column no less, including his picture. Time, helpful as always, said "Imbs rhymes with rims."

Born in 1904 of Scandinavian descent, Imbs was raised in Chicago. When he got to Dartmouth his finances were such that he had to take on several jobs, but slinging hash at Commons wasn't one of them. For one thing, he was a good enough violinist to give lessons. And he was a good enough talker to get a job as the live-in butler in the brand new Occom Ridge house of the then head of the English department. That's right, hitler. Imagine a work-study student doing that today. Imbs was 19 at the time, a bit older than a typical freshman, but apparently he knew to serve from the left, clear from the right. He probably knew a good deal more. Like wine things, even if it was Prohibition.

People came and went in the professor's house, including some Big Names. Probably Rebecca West, certainly Robert Frost. It's likely that Imbs performed his duties satisfactorily. It's also likely that he was taking notes.

Then it was 1925 and Imbs dropped out of Dartmouth. Maybe it was money, maybe he thought he'd learned enough. He took a cattle boat to Europe where, according to Time, he "soon mingled with fan-loving expatriates in Montparnasse." This was long before Language Study Abroad, but he learned the lingo as he went. "The French liked the tone of his voice and thought his Yankee accent charming." That's Time magazine again. He wrote some poetry and a couple of books, including a short autobiography, Diary of Another Young Man. Back then, between the wars, if you were an American ex-pat hanging around Paris it was pretty much de rigueur to join a cultural clique, a salon, and Imbs got in the most famous one, Gertrude Stein's. Its notables included James Joyce and Virgil Thomson and Elliot Paul and Sylvia Beach and, for a time, Pablo Picasso, not to mention Alice B. Toklas.

Sometime later The Atlantic Monthly described Imbs as "...a young novelist fresh from Dartmouth College who served a short term as majordomo" to Gertrude Stein. Well, there's his butlering experience again. Alice B. Toklas, who was herself a kind of literary majordomo, put it this way: "We liked Bravig, even though as Gertrude Stein said, his aim was to please." Toklas said that in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, which, of course, was Stein's work.

Just as he had in that Hanover household, Imbs listened, and learned a great deal from Stein, sifting through her attitudes and utterances. He described one occasion:

"We talked over the afternoon and in the good Parisian way, tore the people to shreds and then sewed them together again by enumerating their virtues. Gertrude's principal diversion was analyzing character, taking people apart, as though they were so many clocks, in order to find the secret springs which motivated their action."

Stein also read drafts of Imbs's writings, pulling no punches in her criticisms. "You have the gift of true brilliancy," she once told him, "and less than anyone should you use crutch phrases. Either the phrase must come or it must not be written at all. For me, if I have something to say, the words are always there. And they are the exact words and the words that should be used. If the story does not come out whole, tant pis.... In my own writing, as you know, I have destroyed sentences and rhythms and literary overtones and all the rest of that nonsense, to get to the very core...the communication of intuition.... All there is to good writing [is] putting down on paper words which dance and weep and make love and fight and kiss and perform miracles."

According to Imbs, when Stein had read The Professor's Wife she asked him to change "one or two words."

At about this time, on an extended vacation in the Baltics, Imbs fell for a young woman who spoke only Russian and German. They were married within weeks and returned to Paris, where Valeska Imbs is said to have read Proust to acquire a mutual language. By 1929 a daughter, Jane, joined the family.

Stem and, more importantly, Alice Toklas were not keen on Valeska or on children. Ostensibly to give Stein more time to write, Toklas decided to shrink the salon by editing out its low-profile members. In his autobiography Imbs remembered that he became persona non grata at rue de Fleurus via a phone call, at a point when Valeska was expecting a second child and was moving to the countryside in anticipation:

"'Hello, I wish to speak to Mr. Bravig Imbs.' 'Speaking.'

'This is Alice Toklas.'

'How pleasant of you to telephone...' (Neither Alice nor Gertrude had ever telephoned me before, but they had just had a telephone installed and were doubtless keen to use it.)

'Miss Gertrude Stein has asked me to inform you that she thinks your plan of sending Valeska to Belley, considering Valeska's condition, a colossal impertinence, and that neither she nor I ever wish to see either you or Valeska again. Miss Gertrude Stein was polite enough to restrain herself last evening, but she thinks your announcement of sending Valeska to Belley without any other friend in the region than ourselves was the coolest piece of cheek she has ever encountered. We never want to see you again,' and bang went the receiver."

Imbs's friendship with Stein was never completely restored, though there were subsequent meetings and a few years later Gertrude contributed a letter when Imbs applied for a Guggenheim which wasn't forthcoming. Bravig would encounter Gertrude out walking her poodle, Basket. "Our meetings were always cordial but she was not as pleasant as she had been before my marriage. She knew I needed money and I think she was afraid I would ask her for some.... Gertrude was generous and often gave money, but she preferred to be generous with painters who could be generous in return, with their drawings and paintings. Then, too, I was no longer a successful young novelist, but a novelist who had failed to place his second book and Gertrude did not want any dead wood in her salon."

When writing didn't pay Imbs's bills there was always his violin, which he would play in the cafes of Paris. At one point before his marriage he hiked down the Loire to the sea, playing the violin for food and drink. "I had a pair of fine hiking boots," he related, "dark blue corduroy knickers and a light blue corduroy suit a favorite costume at Dartmouth to which I now added a Basque beret." His daughter Jane recalls that in the early thirties they were "desperately poor." But a decade later Imbs turned up as the subject of a "Talk of the Town" item in The New Yorker. It seems he was shepherding the designs of one Mme. Bruyere at a Manhattan fashion show on assignment from the Dorland advertising agency, where he worked in Paris.

Advertising, music, translations lmbs was certainly entrepreneurial, but it was for The Professor's Wife that Dartmouth remembered him and not exactly fondly during his short life. All those people felt, well,parodied.

Close scrutiny of the archival keys reveals that there was widespread agreement on just who Imbs was lampooning. From key to key the names match about 90 percent. After all, it was pretty safe for the literary sleuths of the time to speculate that Imbs's "Col. Steinlich" was really Dartmouth's Col. Dietrich, a teacher of fencing and skiing. Professor McWhood of the music department became "MacWhoog," archaeology's Lord became "Hoard." Pretty close. "Maurice Hampden" stood in for Morris Longhurst, another member of the music department. There's even a young man supposedly modeled after Norman Maclean '24, later an author in his own right. (Maclean, of course, wrote about fish, which is safer than professors and their wives.) Author Imbs, who tells the tale in the first person, calls himself "Eric" in the book. Eric the butler. Sounds Scandinavian.

Here's a switcheroo. When The New York Times reviewed the book it decided that the main character was not Delia, the professor's wife, but the professor himself, Myron Ramson. The Times said the book was a political statement about a liberal being out of touch with reality. "The strange thing about this liberal is his complete disinterest in contemporary life as it appears outside the pages of contemporary books." Do you suppose that shook up a few professors back then?

Anyway, here's a flavor of Imbs's writing, a few random quotes from The Professor's Wife. Imbs "Eric" begins his book talking about "Cedar Ridge," for which please read Occom Ridge:

The Ramsons' place was called Otterby. The name was Mrs. Ramson's idea; she got it out of her favorite author, James Barrie; I remember what a shock it was when she told vie she thought Barrie was a greater writer than Shakespeare. "He has the light touch, "shesaid, "that Shakespeare never had."'

Let's acknowledge that occasionally an Imbs sentence will run on until it becomes uncomfortably tangled. For example:

Like most women, she was fussy, and since it was her money thatwas building the house, what she said had some weight, and the housemust have been torn up six times before it was finished, and evenwhen it was finished she wasn't satisfied with the garden gate, but itwas impossible to keep from showing off and entertaining any longer.

And another.

Since the affair was held in the Garden Room, and as it was a musicale a rare thing in Otterby Mrs. Ramson felt she had to wearsomething special, and as her new dresses had not yet arrived herdressmaker was an impoverished Virginia lady of high degree livingin the Blue Ridge Mountains, "fast as good as a Paris modiste," and one of her best examples of economy when she was giving instructions on married life to the brides on Saturday flower-arranging mornings—she wore her black velvet dress with black lace sleevesand a black-and-lace cap like the doges of Venice.

Remember, Imbs was only 24 when The Professor's Wife was published. Maybe he'd read a lot of Victorian authors. My theory: the real-life Delia Ramson talked that way.

Long before Truman Capote's In Cold Blood, Imbs mixed real people with his pseudonymous characters. Robert Frost comes to dinner on Cedar Ridge:

Finally, everyone having finished with coffee and cigarettes, therewas the lull Myron had been impatiently waiting for, and he launchedhis special request and the request of all his guests that Mr. Frost readfrom his own works. On the table at his side were, neatly piled, the slender volumes.

Frost accepted simply and without hesitation. He did not use thebooks but recited from memory. "I think," he said, "I will begin withmy last poem, 'New Hampshire.' It is a kind of outburst. I wrote itwhen I was fed up with Greenwich Village."

There was a holy silence while he recited in a gray, monotonous voice,the soft candlelight lighting his gray hair that curled in a careless fallover his forehead, shadowing his halfclosed eyes. When he came to thewords "sons of bitches," Mrs. Ramson quivered violently. But no onesaw her apologetic smile and she fell to listening once again, more enwrapt than before, her nervous fingers slowly rolling a cigarette to ruin.

"New Hampshire" was indeed published in 1923, just about the time Bravig was butlering in Hanover. But it is Frost's longest poem it goes on for pages and pages and it's hard to imagine Frost ever committed it to memory. It is, however, one of his few poems in which he refers specifically to Dartmouth, although he mentions Harvard as well. And, to be picky, Frost uses the singular "son of a bitch" in the poem, not the plural, though either one would certainly have been enough to set Delia quivering.

Let's wind up with an excerpt to be filed under the Department of Self-Praise, a folder any 24-year-old published author is entitled to stuff.

After the dinner was over, I heard Miss [Rebecca] West talkingto Mrs. Ramson at the "heart of the house" in the hall. She had beensaying admiring things about the house, and then I listened withwide-open ears.

"That butler of yours, where did you pick him up, in England?"she asked.

"Oh, no, he's just a lad from Chicago," said Mrs. Ramson. "Heuses Barrie's Admirable Crichton for a butler's handbook, and wethink he gets on rather well."

"I am more and more amazed at your country," said Miss West. "I never knew that such an intelligent servant class existed."

Wouldn't you like to if Rebecca West actually said that to the real Mrs. R?

Imbs had a good ear and a good eye and he knew character. Besides telling tales out of school, as it were, perhaps his only real fault was writing a few sentences that were too long. Possibly he should have stayed at the College the whole four years and polished his prose. But then he might not have had the opportunity to attach himself to Gertrude Stein.

Well, what became of Bravig Imbs, after Delia Ramson and Gertrude Stein and Mme. Bruyere?

Shortly before the war came, Bravig, a pregnant Valeska, and Jane moved to New York where Bravig got a job at Women'sWear Daily and did translation work on the side. They lived on Washington Square and managed to be part of a sort of mini-salon that included, among others, Virgil Thomson and Anais Nin and Henry Miller. Miller was always hungry, explains Jane Imbs Trimble, "and Valeska was a good cook." She adds, "It was a cheerful, social period. We were brought up with very liberal views, but we were a stable family in a group of unstable artists."

But when war began Imbs itched to get into it, though he was now 36 and the father of three children. He joined the Office of War Information and worked in London with Radio Free Europe, broadcasting to France. He followed the invasion force to Normandy, still broadcasting, giving lessons in English to the French, playing his favorite jazz. The war ended and plans were laid for Valeska and Jane, Peter, and Rosemary to join him in France.

Back to Time magazine, June 10, 1946:

"The mountain road from Grenoble to Marseilles was soggy from the spring rain. An American jeep skidded on a curve, crashed against a tree and overturned. Its driver, an American more loved in France than known in the U.S., was instantly killed. His name was Bravig Wilbur Eugene Imbs.

"To France, it was a tragic loss. Since June 1944, when slender, blond, esthete Imbs...established the first free radio of the OWI in Cherbourg, he has been the darling of the French airwaves, broadcasting as many as five shows a week throughout France. He spoke knowingly of American jive, presented France's best recorded jazz hot, got as many as 400 fan letters a week....At 42, Bravig Imbs had lived a life as full of joie devivre as a French novel."

My guess is, Bravig Imbs didn't much care where novels ended and real life began.

Bravig takes the waterswith Alice B. Toklas andGertrude Stein at Aix-lesBains in 1927. He also tookStein's literary advice—tillToklas pulled the plug. Thenovelist eventually turnedto advertising and radio.

Imbs's love affair with France was mutual. He followed the troops into Normandy after D-Day and became, said Time, "the darling of the French airwaves." In this country his name is all but forgotten.

"We likedBravig..."

"More lovedin France..."

ROBERT NUTT is a freelance writer and contributing editor for thismagazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryAre Americans Saving Enough?

January 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeaturePuppets in the Ivy League

January 1999 By Rich Barlow '81 -

Feature

FeatureA Few Runs at the Skiway

January 1999 By Mark Schiffman '90 -

Feature

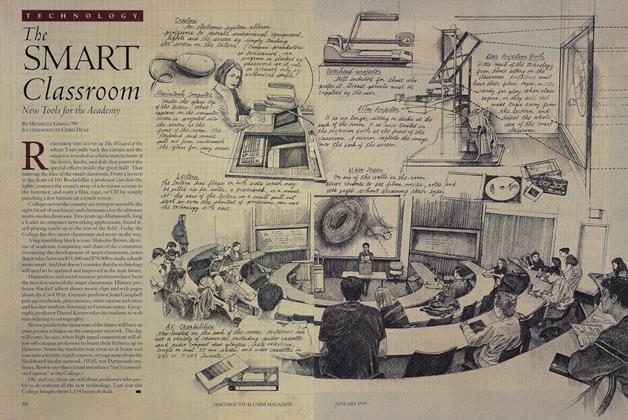

FeatureThe Smart Classroom

January 1999 By Michelle Gregg '99 -

Article

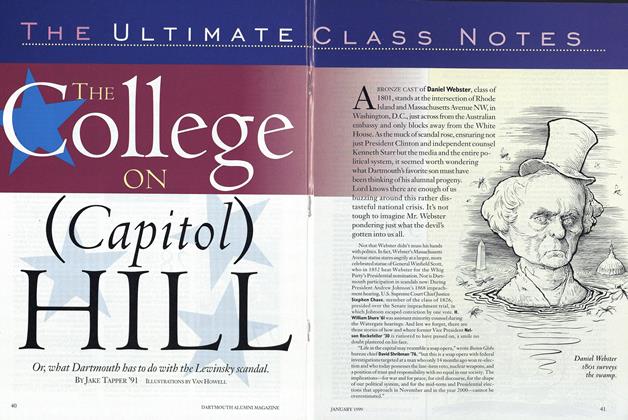

ArticleThe College On (Capitol) Hill

January 1999 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Article

ArticleTales from Uncle Anton

January 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89

Robert H. Nutt '49

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

July 1955 -

Article

ArticleGive Me a D...hmmmmm

May 1994 By Robert H. Nutt '49 -

Article

ArticleDAM GOOD NEWS

June 1994 By Robert H. Nutt '49 -

Article

ArticleTallying the Alumni Fund

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Robert H. Nutt '49 -

Article

ArticleBig Outdoors

OCTOBER 1994 By Robert H. Nutt '49 -

Article

Article3-D in 2-D

April 1995 By Robert H. Nutt '49

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCAMPUS NERVE CENTER

DECEMBER 1963 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Millennial Mindset

Mar/Apr 2011 -

Feature

FeatureKnow Your Place

December 1992 By George J.Demko -

COVER STORY

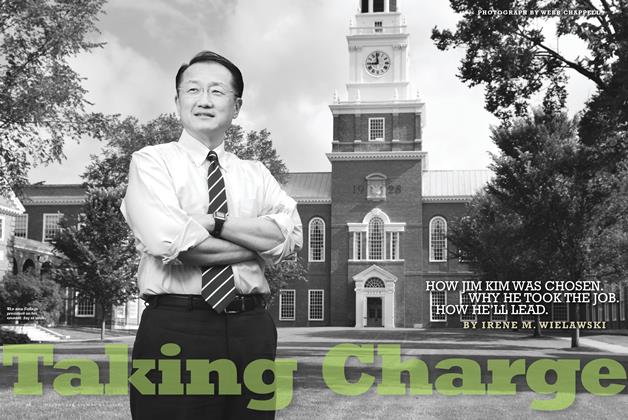

COVER STORYTaking Charge

Sept/Oct 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

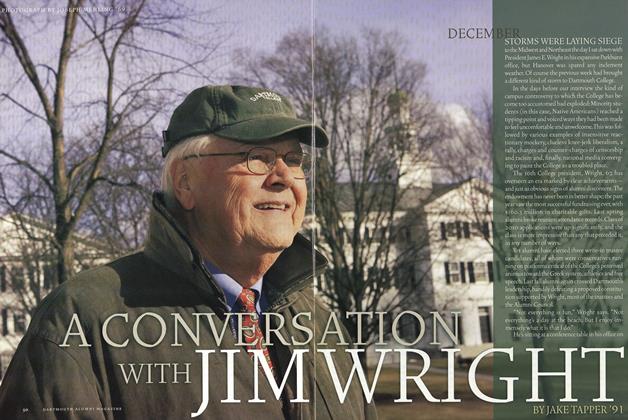

FeatureA Conversation With Jim Wright

Mar/Apr 2007 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOn Mount Washington, where the Geum Peckii blooms and blows

APRIL 1982 By Peter Heller