What does it take to be an outstanding photojournalist? An editor reflects on the genius of Heinz Kluetmeier '65 and James Nachtwey 70.

THE IMAGE IS A DASHING ONE. The photog comes riding into town, loads his many cameras, gets the shots no one else will get, gets the girl, rides off into the sunset. When they made a movie about the photojournalist, they got Clint Eastwood to play the role. Clint Eastwood.

I've been around photogs for a few years now, and I can tell you—the image is pretty accurate. What's unsaid and unasked, however, as with any consideration of image rather than substance, is this: What makes the photog different from the rest of us? And what makes one photog better than his colleagues?

Two of the very best photojournalists in the field today are Greeners. Their beats could not be more different: Heinz Kluetmeier '65 is one of the planet's preeminent sports photographers while James Nachtwey '70 has made his fame in war zones of a different sort: Bosnia, Rwanda, those venues. I've had the privilege of watching both men work, and while I haven't figured it out—why are Kluets and Jim the best of the best?—I've picked up clues.

Heinz and I were on assignment in China in 1988 for Sports Illustrated. We were supposed to sweet talk some government bureaucrats so SI could send in the troops later in the year, with the intention of producing a special issue on sports in China. Heinz and I are both winter-sports fans—we went to Dartmouth, after all, and Heinz is from Minnesota to boot—and so we got it in our heads that we'd also work our way into northern China and prepare a feature on the nation's "icy sports," as the Chinese called skating and sledding. This could be tricky. The far-northern provinces were, back then, hardly up to speed as far as economic development went, and the last thing a Chinese official wanted to allow was an opportunity for anyone, least of all snooping Americans, to view his country as backward. We heard "no" many times as we pressed our suit with the suits during banquet after banquet in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Beijing.

But Heinz wouldn't take no for an answer. I watched him schmooze and seduce during the festivities, and he was really something: gallant, polite without ever being obsequious, slightly ironic (I think for my entertainment). Finally, with the sands running out before our flight home and with our assigned task a complete success—all plans finalized for SI's assault—word came from Beijing that those two pesky journos from the West could go north. This led to some wild doings. I remember waiting at 4 a.m. on a below-zero train platform somewhere up theremust have been Harbin—for a midnight train that never came, then running after another train that was slowing down but not stopping, throwing Heinz's gear aboard and jumping for it, sleeping for an hour in the overhead baggage racks because all seats were already taken with drowsy Chinese, arriving somewhere elsemaybe that was Harbin—and bribing some guy who had a car to take us to some castle where we were supposed to stay, checking in without checking in because, it seemed, we were the only souls in the castle and the door was open. I remember as well being at yet another fancy luncheon—l got real tired of shark-fin soup on that trip—and watching Heinz as he noticed the afternoon light (his light; photogs get proprietary about light) fade beyond the window. He felt he needed a shot of a kids' skating club that was on the ice outside. But he couldn't offend our hosts. I can't quite recall how Heinz hurried the toasts, but he did, and he made his picture before dusk setded.

The thing is: Kluets, though diplomatic and charming, is not a diplomat. He's a photojournalism So a trip to China, no matter the stated raison d'etre, is a waste of time if he doesn't bring back a picture story.

I remember watching Jim Nachtwey on the far end of such a story. The final "selects" were being made by Life magazine editors in anticipation of layouts being produced by the art department. Jim had gone to Thailand, this time, and had documented life and death in an AIDS hospice. In his photographs were drama and pain, some harshness and some tenderness. Each image was beautifully composed; none was gruesome. There was no cheapness in the pictures, and no sentimentality.

I can attest: Editors are, generally, at a place between ambivalent and annoyed about having photographers in the layout room when selects are being chosen. It was evident, though, that things were different with Nachtwey. Life's photo editor at the time, David Friend, who is now editor of creative development at Vanity Fair, solicited Nachtwey's opinion not just about individual images, but about the overarching story, the thread of the piece. I asked David later about this, and he said, "Jim's a rarity these days. He's in the tradition of Eisenstadt, Mydans, Bourke-White. Jim thinks differently about photographs—and Heinz does this, too. He thinks in terms of stories. He goes into these horrific places and makes pictures that are each as artfully composed and revelatory as any photographer's, but it's never just a single image with him. He brings back a narrative. The bullets are flying, and he navigates through these hell zones with a zen-like understanding of how the story is progressing—what's the next shot to make, and the next after that. His colleagues are just in awe of what he produces. An editor would be an idiot not to ask Nachtwey how he sees the story, once the photos are done. Because he sees the story whole. He knows what's important."

Dedication to task, perseverance, putting themselves in the right place at the right moment, and an uncanny instinct for filling the frame—that's the part you call talent—these are several things shared by Nachtwey, Kluetmeier and a very small handful of other photojournalists working today. As Friend said, they are esteemed by their colleagues—and there can be no truer measure of a professional's stature.

I'm not just talking about their camera-toting colleagues. The toughest moment on any given assignment for the word guy is when the action ends. The photographer packages his film and ships it to the lab, then heads for the bar. The word guy takes his notes to his room and sits down to work, envy and resentment blackening his heart. Unless, of course, he has been working alongside such as Heinz or Jim. Then there is no bad feeling. Those guys—they've earned their beers.

ROBERT SULLIVAN, a former senior editor at Sports Illustrated, is assistantmanaging editor at Life. Inferno, a new collection ofJames Nachtwey's photographs, will he publishedby Phaidon in October. Aretrospective of Nachtwey'scareer is scheduled at the International Center for Photography in New York fromOctober through the end ofthe year.

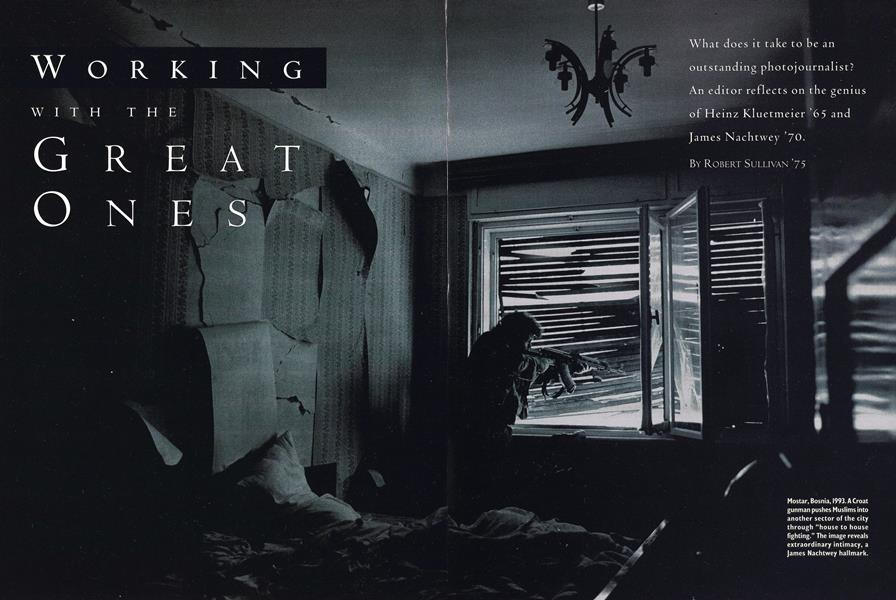

Mostar, Bosnia, 1993.A croat qunman pushes Muslims into another sector of the city through "house to house fighting." The image reveals extraordinary intimacy, a James Nachtwey hallmark.

1992 Olympic gold medal breaststroker Mike Barrowman comes up for air. Kluetmeiers techniques both under water and above push sports photography to an art form.

Diplomacy and perseverance led to this rare shot of a skating club in China's closed northern provinces. One of Kluetmeier's most memorable images also involved ice: the victorious U.S. men's hockey team celebrating at the Lake Placid Olympics.

Thailand, 1996. A woman in the final stages of the disease finds comfort in a Buddhist monastery converted into an AIDS hospice. The assignment was a change of pace for Nachtwey, who is known for documenting political strife around the world.

"HEINZ WOULD not take no for an answer. He couldn't offend our hosts, but he somehow hurried the toasts and made his picture before dusk settled."

"AN EDITOR would be an idiot not to ask Nachtwey how he sees the story. He sees the story whole. He knows what's important."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

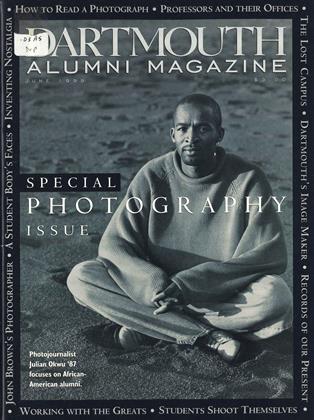

Cover Story

Cover StoryAs We See It

June 1999 By Julian Okwu '87 -

Article

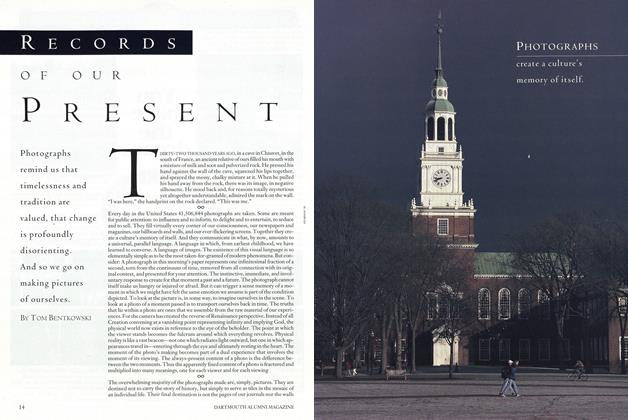

ArticleRecord of Our Present

June 1999 By Tom Bentkowski -

Article

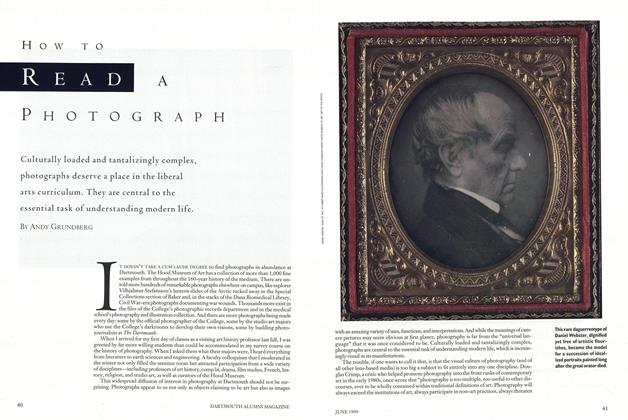

ArticleHow to Read a Photograph

June 1999 By Andy Grundberg -

Article

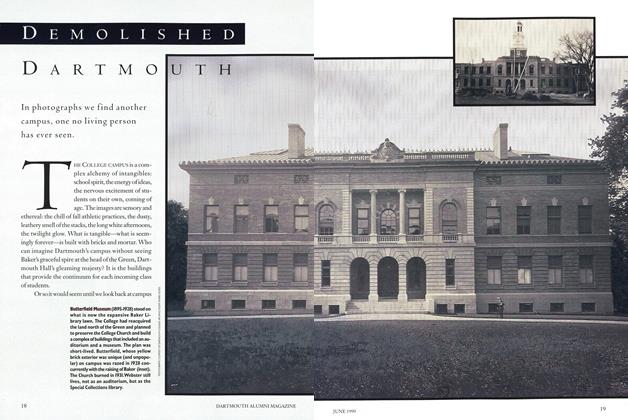

ArticleDemolished Dartmouth

June 1999 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

June 1999 By Jeffrey D. Boylan, R. James "Wazoo" Wasz -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

June 1999 By Mark Soane, Rick Bercuvitz

Robert Sullivan '75

-

Cover Story

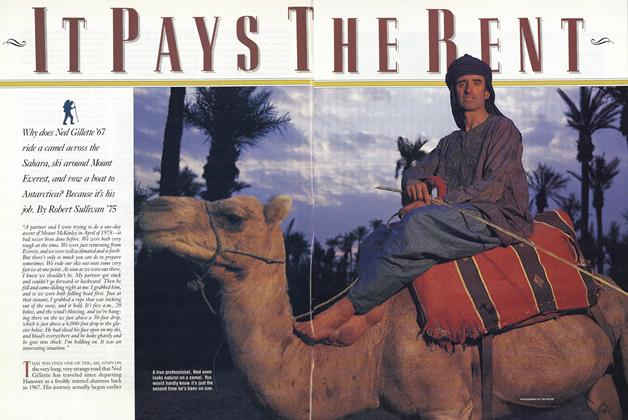

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

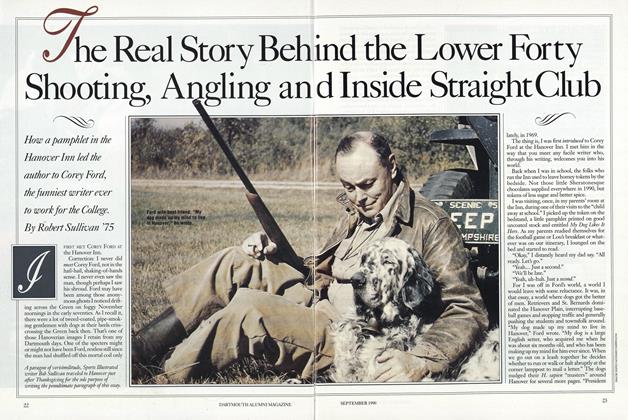

FeatureThe Real Story Behind the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Higher-Ed Book Biz

JUNE 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

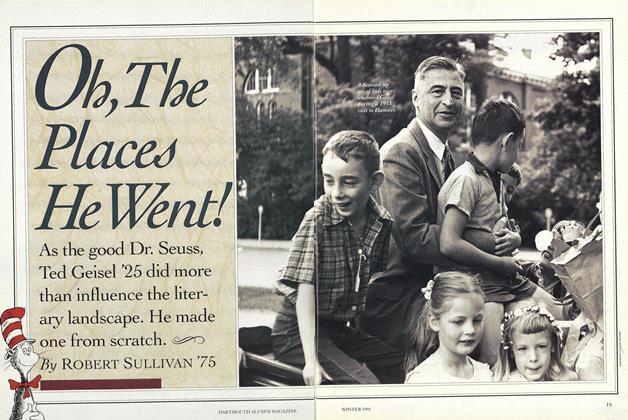

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleFootball From Down Under

December 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureOld School New School

March 1998 By Robert Sullivan '75