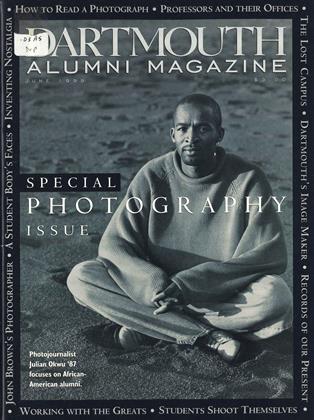

Culturally loaded and tantalizingly complex, photographs deserve a place in the liberal arts curriculum. They are central to the essential task of understanding modern life.

IT DOESN'T TAKE A CUM LAUDE DEGREE to find photographs in abundance at Dartmouth. The Hood Museum of Art has a collection of more than 1,000 fine examples from throughout the 160-year history of the medium. There are untold more hundreds of remarkable photographs elsewhere on campus, like explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson's lantern slides of the Arctic tucked away in the Special Collections section of Baker and, in the stacks of the Dana Biomedical Library, Civil War-era photographs documenting war wounds. Thousands more exist in the files of the College's photographic records department and in the medical school's photography and illustration collection. And there are more photographs being made every day: some by the official photographer of the College, some by the studio art majors who use the College's darkrooms to develop their own visions, some by budding photojournalists at The Dartmouth.

When I arrived for my first day of classes as a visiting art history professor last fall, I was greeted by far more willing students than could be accommodated in my survey course on the history of photography. When I asked them what their majors were, I heard everything from literature to earth sciences and engineering. A faculty colloquium that I moderated in the winter not only filled the seminar room but attracted participation from a wide variety of disciplines—including professors of art history, comp lit, drama, film studies, French, history, religion, and studio art, as well as curators of the Hood Museum.

This widespread diffusion of interest in photography at Dartmouth should not be surprising. Photographs appear to us not only as objects claiming to be art but also as images with an amazing variety of uses, functions, and interpretations. And while the meanings of cam era pictures may seem obvious at first glance, photography is far from the "universal language" that it was once considered to be. Culturally loaded and tantalizingly complex, photographs are central to the essential task of understanding modern life, which is increasingly visual in its manifestations.

The trouble, if one wants to call it that, is that the visual culture of photography (and of all other lens-based media) is too big a subject to fit entirely into any one discipline. Douglas Crimp, a critic who helped promote photography into the front ranks of contemporary art in the early 1980s, once wrote that "photography is too multiple, too useful to other discourses, ever to be wholly contained within traditional definitions of art. Photography will always exceed the institutions of art, always participate in non-art practices, always threaten the insularity of art's discourses." The same could be said about photography within academic life. It is, by nature, an interdisciplinary subject, since it exceeds traditionally organized categories of knowledge, which are based on the primacy of a verbal and literary culture.

But calling photography a "subject" is perhaps a wrong approach. Rather than seeing it as the end of intellectual inquiry, we might more usefully consider it a medium through which students can discern how knowledge is constituted across a broad range of disciplines. The study of photographs yields rewards that are not merely aesthetic. It introduces ideas about how representation is coded by culture, about how lenticular vision reflects a particular (and, for many cultures, peculiar) relationship between observer and observed, and about how reality and veracity often make strange bedfellows.

Take, for example, a picture titled The Fisherman, Ojibway Indian, Northern Minnesota, from the Hood Museum's collection. Taken in 1908 by Roland W. Reed, its brown tones and hazy atmosphere speak to us of an earlier era, one in which men like the fisherman in the picture communed as one with nature. As an apparent document of Ojibway life, it evokes admiration for the Native American and sadness at what we might imagine to be his impending disappearance in the face of Manifest Destiny. But Reed's picture is a fantasy, a kind of latter-day Last of the Mohicans done in the style of Pictorialism, which tells us that the picture is less a document than a work of art. By 1908 the locomotive of Manifest Destiny had long since passed Minnesota by; like his contemporary Edward S. Curtis, Reed was simply manufacturing nostalgia using Native Americans as his actors.

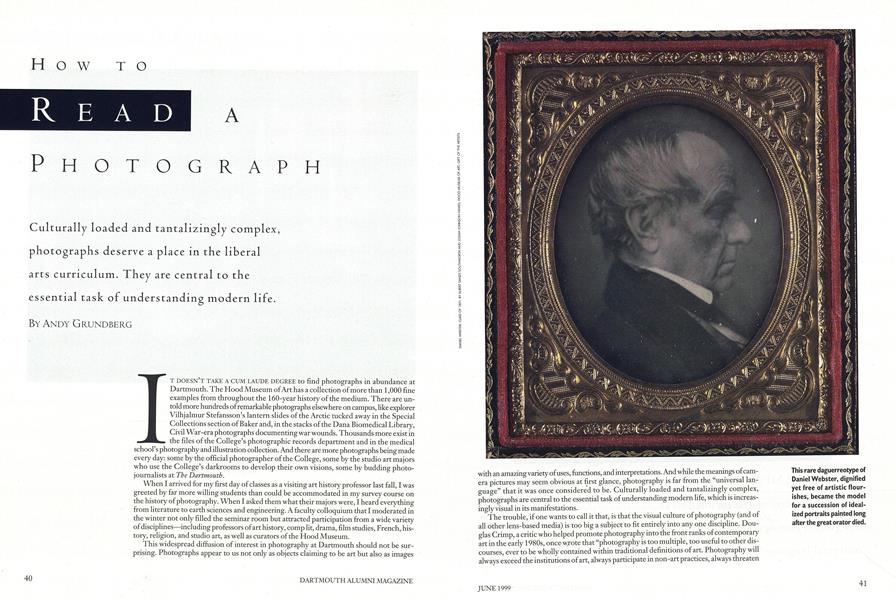

Another intriguing example of ethnographic interest is the Hood Museum's invaluable daguerreotype of Daniel Webster. A gift to the College from the renowned Boston studio of Southworth and Hawes, the image once resided in the College's collection of portraits of distinguished founders, alumni, and presidents. After Webster's death it may have served painters as a model for the jurist's visage, allowing for a long procession of Webster portraits in oil. The photograph, however, is different in kind from the paintings. It shows the actual man as he appeared before the lens shortly before his death in 18 52, his appearance dignified but hardly idealized, free of any artistic flourishes such as gathering clouds or campus spires in the background. Given the daguerreotype's remarkable intimacy, we view the picture as if Webster were somehow immanent within the plate, his life preserved by the remarkable "mirror with a memory."

I would not dispute the claim that both of these pictures are examples of the art of photography and therefore belong in an art museum. Nor would I dispute the notion that the Special Collections trove of Edward Curtis's multi-volume work The North American Indian belongs in a library—although it, too, is a work of art. The germane point is that these and many other photographs lead us far afield from the conventional concerns of art history style, influence, canonical importance. Students of American history, government, Native- American studies, and film studies could well provide fresh and intriguing insights into the manifold meanings of these pictures, placing them in critical frameworks that reconsider the relationships between images, their makers, and their viewers.

The challenge for Dartmouth is to provide the kind of access that will allow for such a multitude of interpretations, as well as a critical framework that will inform them. During my time on campus I became aware of a number of intriguing attempts to meet this challenge. Photographs have been discussed in courses devoted to French Surrealist literature, for example, and the Hood Museum has collaborated with professor Marianne Hirsch on an exhibition and symposium about family photographs and memory. These examples suggest that photography already has a pervasive presence within the curriculum, albeit one that is so suffused as to be nearly unnoticeable.

Clearly the museum, the library system, and the College's academic departments and programs are all linked by photography, and their ongoing cooperation and collaboration is a precondition for extending the role photography now plays in the curriculum. This should not be any harder than locating photographs on campus. They, and we, simply need to keep in mind that looking at photographs isn't about eye candy; in today's superheated visual culture, understanding how to interpret photographs is a necessary critical skill, and one that all Dartmouth should possess.

ANDY GRUNDBERG, a critic, curator, and teacher best known for his writings in The New York Times, was recently in residence at Dartmouth's Hood Museum of Art to promote the use of its collections in the curriculum. A new and expanded edition of his collected essays, Crisis of the Real, willhe released later this year by Aperture.

This rare daguerreotype of Daniel Webster, dignified yet free of artistic flourishes, became the model for a succession of idealized portraits painted long after the great orator died.

Roland Reed's photo of an Ojibway fisherman doesn't reflect reality. It is a fantasy done in the style of Pictorialism. Experts now read the image as a work of art rather than documentation.

WHILE THE MEANINGS of camera pictures may seem obvious at first glance, photography is far from the "universal language."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryAs We See It

June 1999 By Julian Okwu '87 -

Article

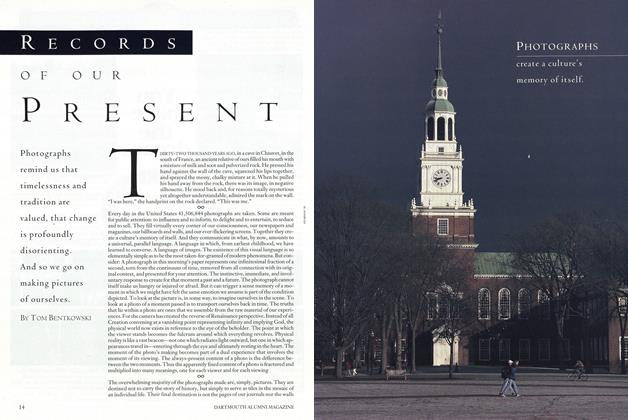

ArticleRecord of Our Present

June 1999 By Tom Bentkowski -

Article

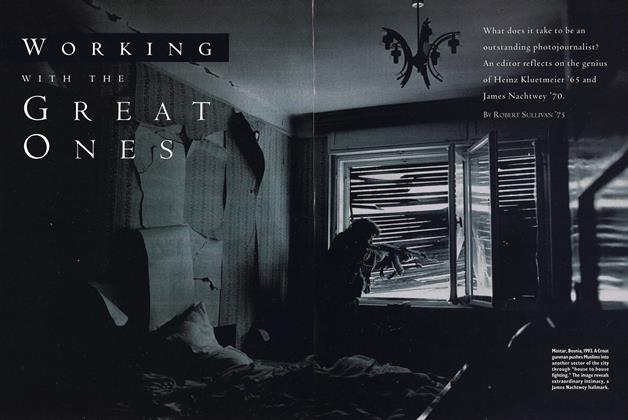

ArticleWorking with the Great Ones

June 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

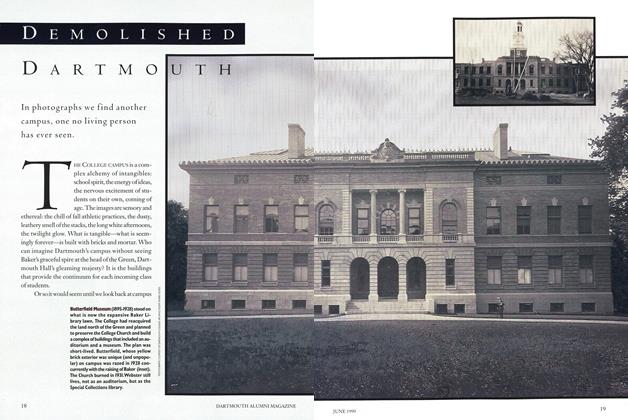

ArticleDemolished Dartmouth

June 1999 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

June 1999 By Jeffrey D. Boylan, R. James "Wazoo" Wasz -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

June 1999 By Mark Soane, Rick Bercuvitz