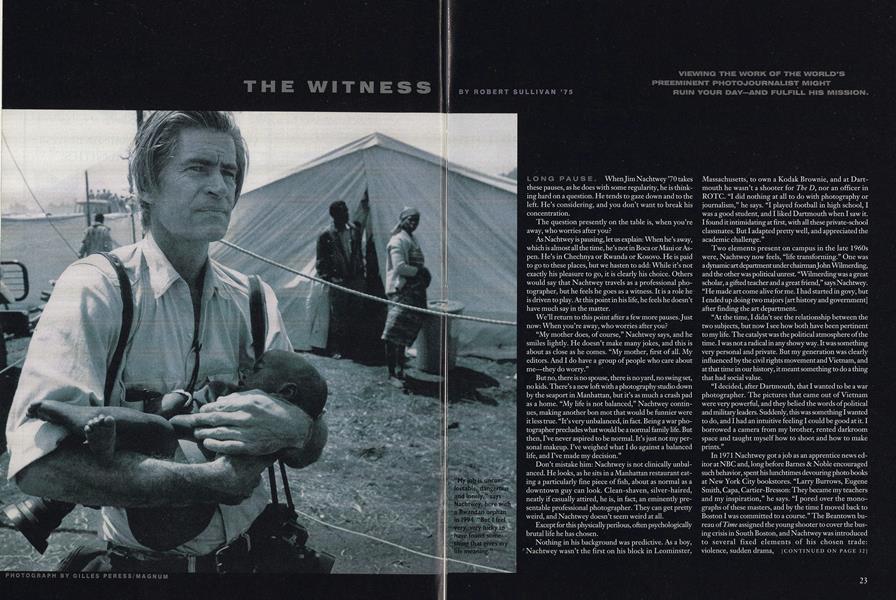

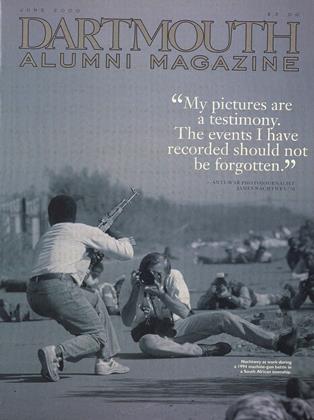

The Witness

Viewing the work of the world’s preeminent photojournalist might ruin your day—and fulfill his mission.

JUNE 2000 ROBERT SULLIVAN '75Viewing the work of the world’s preeminent photojournalist might ruin your day—and fulfill his mission.

JUNE 2000 ROBERT SULLIVAN '75VIEWING THE WORK OF THE WORLD'S PREEMINENT PHOTOJOURNALIST MIGHT RUIN YOUR DAY—AND FULFILL HIS MISSION.

LONG PAUSE, When Jim Nachtwey '70 takes these pauses, as he does with some regularity, he is thinking hard on a question. He tends to gaze down and to the left. He's considering, and you don't want to break his concentration.

The question presently on the table is, when you're away, who worries after you?

As Nachtwey is pausing, let us explain: When he's away, which is almost all the time, he's not in Boca or Maui or Aspen. He's in Chechnya or Rwanda or Kosovo. He is paid to go to these places, but we hasten to add: While it's not exactly his pleasure to go, it is clearly his choice. Others would say that Nachtwey travels as a professional photographer, but he feels he goes as a witness. It is a role he is driven to play. At this point in his life, he feels he doesn't have much say in the matter.

We'll return to this point after a few more pauses. Just now: When you're away, who worries after you?

"My mother does, of course," Nachtwey says, and he smiles lightly. He doesn't make many jokes, and this is about as close as he comes. "My mother, first of all. My editors. And I do have a group of people who care about me—they do worry."

But no, there is no spouse, there is no yard, no swing set, no kids. There's a new loft with a photography studio down by the seaport in Manhattan, but it's as much a crash pad as a home. "My life is not balanced," Nachtwey continues, making another bon mot that would be funnier were it less true. "It's very unbalanced, in fact. Being a war photographer precludes what would be a normal family life. But then, I've never aspired to be normal. It's just not my personal makeup. I've weighed what I do against a balanced life, and I've made my decision."

Don't mistake him: Nachtwey is not clinically unbalanced. He looks, as he sits in a Manhattan restaurant eating a particularly fine piece of fish, about as normal as a downtown guy can look. Clean-shaven, silver-haired, neatly if casually attired, he is, in fact, an eminently presentable professional photographer. They can get pretty weird, and Nachtwey doesn't seem weird at all.

Except of this physically perilous,often psychologically bruatal life he has chosen.

Nothing in his background was predictive. As a boy, Nachtwey wasn't the first on his block in Leominster, Massachusetts, to own a Kodak Brownie, and at Dartmouth he wasn't a shooter for The D, nor an officer in ROTC. "I did nothing at all to do with photography or journalism," he says. "I played football in high school, I was a good student, and I liked Dartmouth when I saw it. I found it intimidating at first, with all these private-school classmates. But I adapted pretty well, and appreciated the academic challenge."

Two elements present on campus in the late 1960s were, Nachtwey now feels, "life transforming." One was a dynamic art department under chairman J ohn Wilmerding, and the other was political unrest. "Wilmerding was a great scholar, a gifted teacher and a great friend," says Nachtwey. "He made art come alive for me. I had started in govy, but I ended up doing two majors [art history and government] after finding the art department.

"At the time, I didn't see the relationship between the two subjects, but now I see how both have been pertinent to my life. The catalyst was the political atmosphere of the time. I was not a radical in any showy way. It was something very personal and private. But my generation was clearly influenced by the civil rights movement and Vietnam, and at that time in our history, it meant something to do a thing that had social value.

"I decided, after Dartmouth, that I wanted to be a war photographer. The pictures that came out of Vietnam were very powerful, and they belied the words of political and military leaders. Suddenly, this was something I wanted to do, and I had an intuitive feeling I could be good at it. I borrowed a camera from my brother, rented darkroom space and taught myself how to shoot and how to make prints."

In 1971 Nachtwey got a job as an apprentice news editor atNBC and, long before Barnes & Noble encouraged such behavior, spent his lunchtimes devouring photo books at New York City bookstores. "Larry Burrows, Eugene Smith, Capa, Cartier-Bresson: They became my teachers and my inspiration," he says. "I pored over the monographs of these masters, and by the time I moved back to Boston I was committed to a course." The Beantown bureau of Time assigned the young shooter to cover the busing crisis in South Boston, and Nachtwey was introduced to several fixed elements of his chosen trade: violence, sudden drama, [continued from page 23] danger."The whole thing was very divisive and ugly, but I had the sense that history was changing and I was reporting an important historical event, which mattered greatly to me," he recalls. "And I sensed I was handling it pretty well. Once, I was covering an anti busing parade in Southie and I got off the main street. I was surrounded by a gang of very threatening high school kids. One punched me in the face. But I eased out of that situation. I somehow handled it. My first instinct was to jump them and fight, but I realized the film would have been destroyed. I got out, I got the film out. I had the sense right then that this was a role for me to play."

David Friend, former photo editor at LIFE and now editor of creative development at Vanity Fair, says Nachtwey's behavior in the field is as special as it is instinctive: "The bullets are flying, and he navigates through these hell zones with a zen-like understanding of how the story is progressing—what's the next shot to make, and the next after that. He sees the story whole as he kind of floats through the war."

"It feels very fast," Nachtwey says, trying to explain. "It all happens very fast, and you're composing a shot in an instant, then moving. I've been a target a few times, and I kept moving. I was very lightly wounded by a land mine in El Salvador, got some shrapnel in Lebanon, had a tear gas canister from a shotgun blown into my knee by riot police in Korea. Someone opened my lip in Indonesia. You keep moving if you can."

Nachtwey, who works for Time and Magnum Photos, has seen colleagues killed and has recorded landscapes that—same time, next day—were obliterated. "I try not to be reckless, but even still, I have been lucky."

Ed Barnes, a Time reporter who has covered killing fields alongside Nachtwey, knows how lucky. "In Afghanistan during the fighting for Kabul we were on the front lines with Massoud's forces, and Nachtwey was always pushing to get one step closer to the picture, trying to make it to the next trench. Most of the time the Afghans just fought artillery duels but one day it looked like Massoud was about to make a major assault. It was rare for the two sides to fight pitched battles, so the pictures would have been important. Jim kept pushing forward until the unit he was with got cut off by the Taliban. They fired a rocket-propelled grenade directly at him. It landed at his feet but didn't explode. The Arabs have a word for that kind of luck, it is called baraka, and it means that one has a mission and a personality that Allah watches over. Jim has baraka. And, of course, there is much more to it than luck."

Nachtwey's baraka followed him from the streets of Irish South Boston to those of Belfast, then throughout the world. Back in the New York City offices of various magazines, his reputation grew as an artist, a throwback to the storied combat photographers, a sure bet—perhaps the best bet in the business—and a bit of an obsessive. "He never seems to drift from the core of the story," says Barnes. "While other journalists may sit around after a bad and bloody day and vent, Jim is always the guy planning for tomorrow. He doesn't seem to look back. He reminds me of Ahab with a heart, whose personal Moby-Dick is the one great picture of war."

In fact, Nachtwey's nemesis is not the missing picture. It's injustice.

He is asked, at lunch, how much longer he'll do what he does.

Long pause.

"I think I have years to go yet," he says finally. Another pause. "Yes, of course, this takes a lot out of you," he says. "It's emotionally difficult. I have come close to despair on several occasions, dangerously close to losing my faith in humanity. In Rwanda in particular, I grew very depressed and that lasted for at least two years.

"My job is uncomfortable, dangerous and lonely. But I feel very, very lucky to have found something that gives my life meaning."

He does not mean photography, he means serving as a witness. Nachtwey's photos, all of them, have points of view, and Nachtwey doesn't apologize for this. "There's a tension between the objective and the subjective in reporting," he says. "The feelings you have about what you've witnessed—anger, disbelief, compassion those feelings have to be channeled into your photographs. In front of you are objective facts, but photography is a process of selection: howyou perceive the light, whatyou leave out of the frame These are all factors in creating a certain effect, and I want to create an effect."

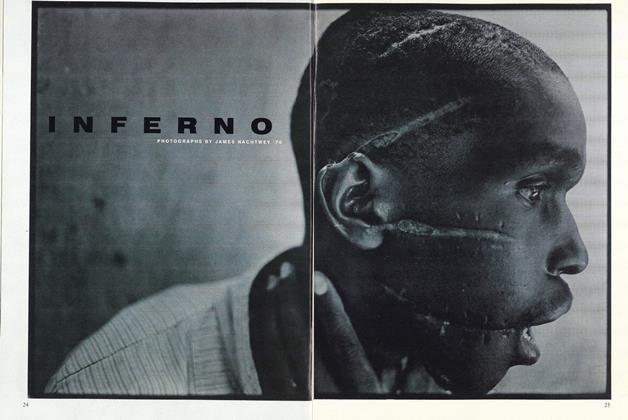

For overwhelming effect, there is now Inferno, Nachtwey's anchor of a book (Phaidon Press). It is immense (480 pages), often unbearable and heartbreaking. "It's about the last decade of the 20th century," says Nachtwey. " When I discovered a gulag of orphanages in Romania in 1990,1 had no idea I was starting on a book. But then famine in Somalia in 1992—a war-induced famine, starvation as a means of mass destruction—then India in 1993, the Sudan in 1993—starvation again as a weapon of mass destruction—then Bosnia, 1994 in Rwanda, Chechnya, Kosovo. Before the breakup of the Soviet Union, conflict had a different nature. Even proxy wars more or less resembled war. But now there is a shift in the level of hatred, and the vast majority of victims are civilians. The book is about crimes against humanity. All of these are, simply put, crimes against humanity."

The pleasant lunch is two days in the past, and Nachtwey is now embarking on a mission he finds "much more terrifying than war." He's setting forth on a book tour. Upstairs at the Barnes & Noble on Union Square, he stands nervously aside as writer Luc Sante, who wrote the foreword for Inferno, finishes an introduction: "Nachtwey translates cries into pictures.. ..He shows the humanity and specificity of his subjects... .He never allows himself the protection of cynicism. .. .It is my great privilege to introduce..."

Nachtwey takes the podium and leads the standing-room-only audience through a series of wrenching slides: "Something happened to me inside these orphanages. The victims were staring me in the face and it shook my faith. I did not want to see this... .You do suffer compassion fatigue, but what allows me to overcome the emotional response is the knowledge that the images will raise compassion....When I discovered this family in Somalia the father could go no further and, after taking this picture, I put the family in my vehicle and took them to the feeding center... This girl was tied to a bench in an Indian brothel where her mother was working inside.. ..Being a witness, I think it is very important to be honest, to be eloquent and to be powerful. Now, these next pictures are quite often difficult to look at, but I see them as a challenge This picture from Bosnia shows a bedroom as a battleground. Here's a place where people have their most intimate moments, where life itself was conceived, now turned into a killing field.. ..In the past I had a very clear idea of what was happening, but Rwanda was different. These were the people who had actually committed the genocide, and now the cholera epidemic was taking the innocent along with the guilty indiscriminately... .These people were dying in such numbers they had to be buried with bulldozers. .. . Anywhere you were in Grozny, at any time of the day, you could be taken out. Shells were literally falling everywhere... .This is in No Man's Land. A good friend and colleague had been taken, and I walked across with another friend and a flag and we got him out of there and back behind Chechnyan lines. When they took him, they had thought he was someone he wasn't...."

Long pause.

"I have been a witness, and these pictures are my testimony. Thank you."

During the Q&A, Nachtwey says at one point, "I'm not a photographer for the sake of photography. I didn't choose to be a photographer. I chose to be a war photographer. With a camera, I could be a witness. I could make these pictures that...."

Short pause.

"I don't want to let people off the hook. I don't want to make these pictures easy to look at. I want to ruin people's day if I have to. I want to stop them in their tracks and make them think of people beyond themselves." Longer pause.

"I don't give myself a lot of down time. I don't feel I have a lot of time. I feel I have to be as useful as I can while I can. "Mine is not a balanced life."

Some in the audience take it as a punchline and laugh for the first time this evening. Others, sensing an extraordinary degree of truth, are uneasy, unsure. But even in their disquiet, they are grateful for Natchwey. With their applause which is solemn, prolonged and deeply felt they thank him for ruining their day.

"My job is uncom- fortable, dangerous and lonely," says Nachtwey, here with a Rwandna orphan in 1994. "But I feel very, very lucky to have found something that gives my life meaning.

"My job is uncomfortable, dangerous and lonely," says Nachtwey, here with a Rwandna orphan in 1994. "But I feel very, very lucky to have found something that gives my life meaning.

TESTIMONY On May 23 the International Center of Photography in New York City opens JamesNachtwey: Testimony, a month-long exhibit of the photojournalism work. Featuring more than 150 images taken since 1981, the exhibit will also honor Nachtwey as this year's recipient of the Center's Infinity Award for Photojournalism. (This year marks his third Infinity Award; Nachtwey is also a five-time recipient of the Robert Capa Gold Medal Award and has been named Magazine Photographer of the Year six times.) Admission is $6. For more information, contact the International Center of Photography at (212) 860-1777.

ROBERT SULLIVAN, an editor at LIFE since 1993, recently joined Time magazine. His latest book is Atlantis Rising (Simon & Schuster).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Class of 2000 Takes Off

June 2000 By STEPHANIE EDWARDS ’00 -

Feature

FeatureInferno

June 2000 -

Article

ArticleMinding the Public's Business

June 2000 By President James Wright -

First Person

First PersonTaking Chances

June 2000 By Retina Barreca ’79 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1972

June 2000 By Bill Price -

On the Hill

On the HillCampus News and Notes

June 2000 By Jen Whitcomb '00

ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

-

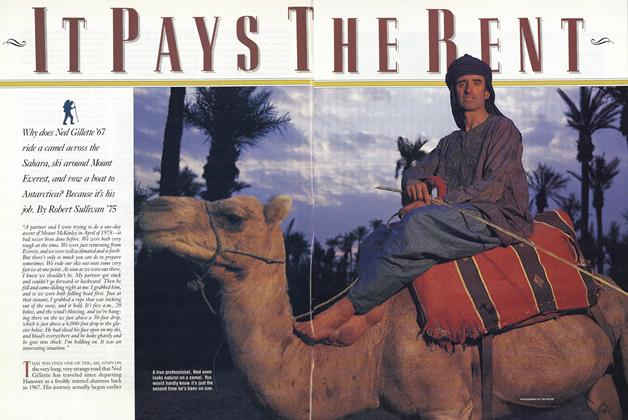

Cover Story

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

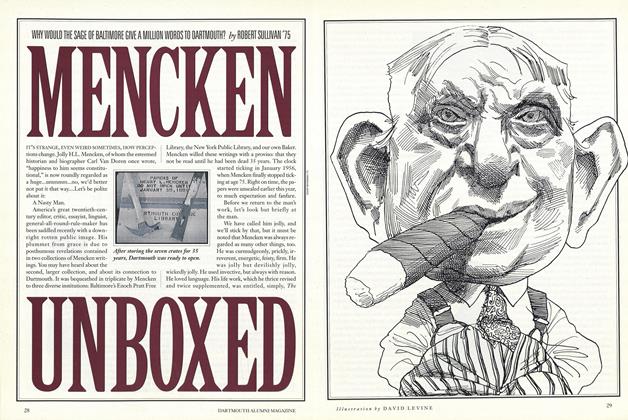

Feature

FeatureMENCKEN UNBOXED

OCTOBER 1991 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

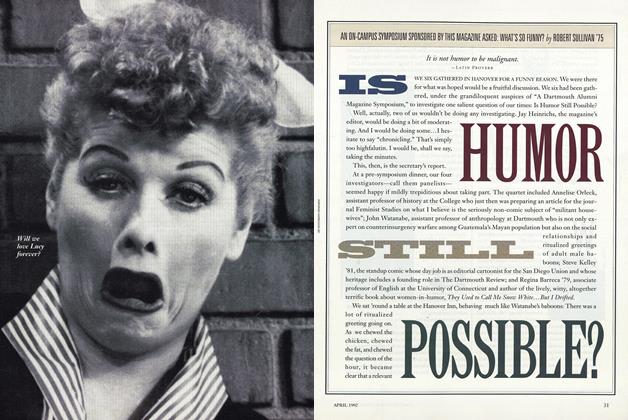

Cover Story

Cover StoryIS HUMOR STILL POSSIBLE?

APRIL 1992 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

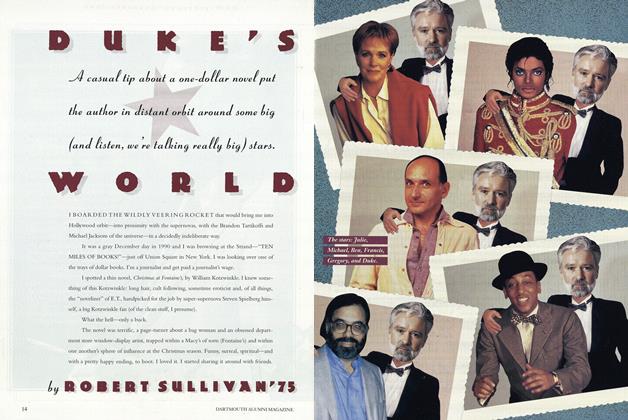

Feature

FeatureDUKE'S WORLD

February 1993 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySanta: The Dartmouth Connection

DECEMBER 1996 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhat Does Dartmouth Cry For?

MARCH 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75