The Day I Saw The Bullet Cry

How a third-string tackle called the greatest sneak play in Bob Blackman’s coaching career.

Nov/Dec 2000 John Murphy ’58How a third-string tackle called the greatest sneak play in Bob Blackman’s coaching career.

Nov/Dec 2000 John Murphy ’58How a third-string tackle called the greatest sneak play in Bob Blackman's coaching career.

ADECADE AGO, I STAGED A REUNION of football coach Bob Blackman's lettermen from the first five years he coached at Dartmouth. It was a little selfish of me to focus on the years just ahead and behind my own class, but I wanted to know everyone. I rented a banquet hall in a hotel in New York City. Nearly 40 players showed up, all in various stages of middle age, some not having changed a bit. Including Coach Blackman.

Some of us hadn't seen each other for 35 years, but we quickly realized we had something more than the past in common. Dave Bradley'58, our quarterback, told us about his recurring dream of Blackman screaming at him for calling the wrong play. The wife of Sam Bowlby '60 described how right before the reunion Sam awoke from a nightmare slugging his pillow and screaming, "I missed the block! I missed the block!"

Just before dinner, someone blew a whistle. It was Coach Blackman. He'd brought his camera and he wanted a group picture. He pointed everyone in the direction of the stairs. "Linemen over there," he barked. "Backs over there."

Suddenly we were back in boot camp with The Bullet. The memories took over.

BLACKMAN, WHO DIED IN MARCH, had arrived in Hanover in the spring of 1955 from the University of Denver, winner of the Skyline Conference. I was on the first Dartmouth team he coached. I didn't make the road trips until the following year, so I missed the bus ride back from Colgate after Blackman's first Dartmouth game, the one where we led by 20 points at halftime but lost 21-20.I heard it was a long ride, with Blackman stopping every 30 miles to vomit.

Our new leader took over Dartmouth and our young lives like no one else. The Ivy League allowed coaches only one day in the spring to get together with the team. Blackman's meeting lasted from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. on a Sunday in March. He detailed his expectations. In that one day, Blackman gave new meaning to the word "driven."

He instructed us on everything. Players were forbidden to let their shirts hang out. God forbid you thoughtyou'd be like Lennie Moore of the Baltimore Colts and tape your cleats to your socks. "Get a pair of cleats that fit," Blackman would say. If you ran off the field and threwyour helmet in disgust, Blackman would scold, "I know you screwed up. You know you screwed up. Why let everybody in the stadium know?" Then he'd blast you with the worst insult of all: "You're acting like you're still in high school!"

Blackman was a perfectionist. Before every practice, each player received a mimeographed sheet with charts and timetables on it, telling him what he was going to be doing every minute he was on the field: "2:00 to 2:15, calisthenics, warm up; 2:15 to 2:45, linemen, quarterback, halfbacks, one-on-one handoff drill." After every game, the coaches assembled a booklet, sometimes with as many as 35 pages, for every player. In it were descriptions of what that player was doing—and what he was supposed to be doing—on every play. You weren't allowed any excuses. It was a true meritocracy. If you didn't get much playing time, you knew why. And so did everyone else.

Blackman was as innovative as he was demanding. He was the first to use stunting defensive linemen. His V formation predated so many things that college teams are just now getting used to it. Today they call it the wishbone. When we were receiving kicks, Blackman always had two players who waited for the ball, and they worked a reverse on every kickoff and punt return. There was either a fake reverse or a real reverse, depending on which side of the field the play was supposed to go and where we were supposed to block.

When we were kicking off, we had three kickers running toward the ball, which was always placed on the hash mark. One of the players was actually going to kick it, and the other two were making believe it was an onside kick. For hours we'd practice the onside kick, end over end, and Blackman would show how miraculously the ball always took the biggest hop just after it went the obligatory 10 yards. That miracle hop helped us tie Yale my senior year.

Blackman got the name "Bullet Bob" from J.C. Parkes '57, who also named the coach's Oldsmobile the "Bulletmobile," a.k.a. "The Car that Runs on Desire." Parkes would forget a play and immediately become the object of Coach's derision: "Holy smokes, J.C., how do you expect to be a doctor when you can't even remember who you're supposed to block?" Parkes got even by outlining, in the huddle out of Blackman's earshot, what he'd like to do with various body parts of The Bullet during surgery. He also got even by thinking up songs like this one:

One more week and we'll be freeFrom this awful miseryBye bye, Blackman.

No more shocks, no more joltsPunt returns or Wilbur VolzBye bye, Blackman.

NOW ALL THESE YEARS LATER, Parkes, who did become a doctor—an orthopedic surgeon for the New York Mets—sang The Bullet's praises at our reunion. So did Dave Bathrick '58, a professor of German literature at Cornell, and Bob Adelizzi '57, a banker. I spoke last.

I presented Kay, The Bullets wife, with a dozen roses. Then I talked about how each person in the room would agree that the most profound influence on each and everyone of us during our four years at Dartmouth came not from the professors we had two or three times a week for one semester. It came from Blackman and his assistant coaches—-Jack Musick, Wilbur Volz, Elmer Lampe—who over and over again taught us about organization and planning, creativity and tenacity, follow-through and accountability, and that hard work would be rewarded.

"Lets'get this right out in front, Bob," I said. (That was the first time I ever called him Bob.) "You never went to the Rose Bowl." I paused to let it sink in. "You took Pasadena Junior College to the Junior College Rose Bowl, and we all soon learned that the biggest dream in your life was to bring a team to Pasadena and win the Rose Bowl on New Year's Day. Of course, the Ivy League doesn't send a team to the Rose Bowl, so we all knew one day we might lose you to the Big Ten as you pursued your dream. But how many coaches who have been to the Rose Bowl can point to the College Football Hall of Fame and the success you've had and the influence you've had on the lives of so many men, of Dartmouth and on all of us, everywhere you've coached?

"Coach Blackman, please step forward."

As he approached, I reached under the podium and held up a silver cup. I read the inscription: "To Coach Robert Blackman, with deep appreciation, from your players on the Dartmouth Football Teams, the Classes of 1956,1957,1958, 1959 and 1960."

I handed him the cup, walked over to his wife and picked up the bouquet I had given her a few moments before. I placed the bouquet inside the cup that Blackman was holding.

"In case you didn't notice, Coach," I said. "Finally. A Rose Bowl."

That was when I saw the tears.

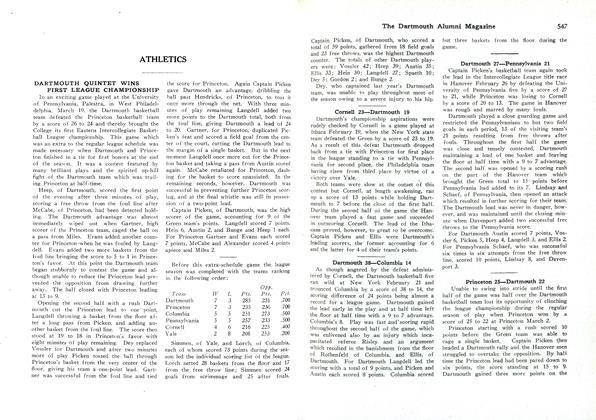

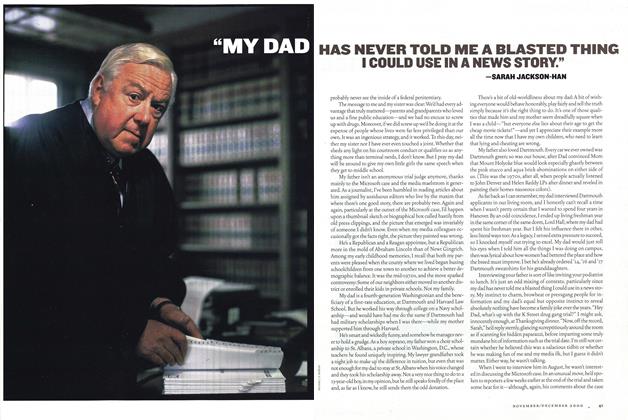

Big Green Glory Mementos fromBob Blackman's first five years atDartmouth include the 1958 championship plaque. Group photo wastaken at the reunion; player picturedat bottom center is the author.

JOHN MURPHY is a trial lawyer in Hartford,Connecticut. During four years on the footballteam, he never rose above third-string left tackle. As a senior, he won the Manners MakythMan Award, which he says is given to theplayer "most willing to hang around for fouryears and hold onto blocking dummies for themore skillful members of the team."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

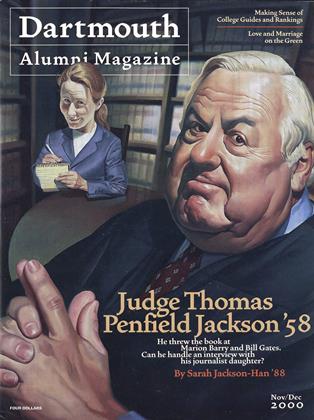

Cover StoryFather In Law

November | December 2000 By SARAH JACKSON-HAN ’88 -

Feature

FeatureAnd the Bride Wore Green

November | December 2000 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Junkie

November | December 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureWISDOM OF THE GUIDES

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureOVER-RATED

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureWHAT STUDENTS SAY

November | December 2000