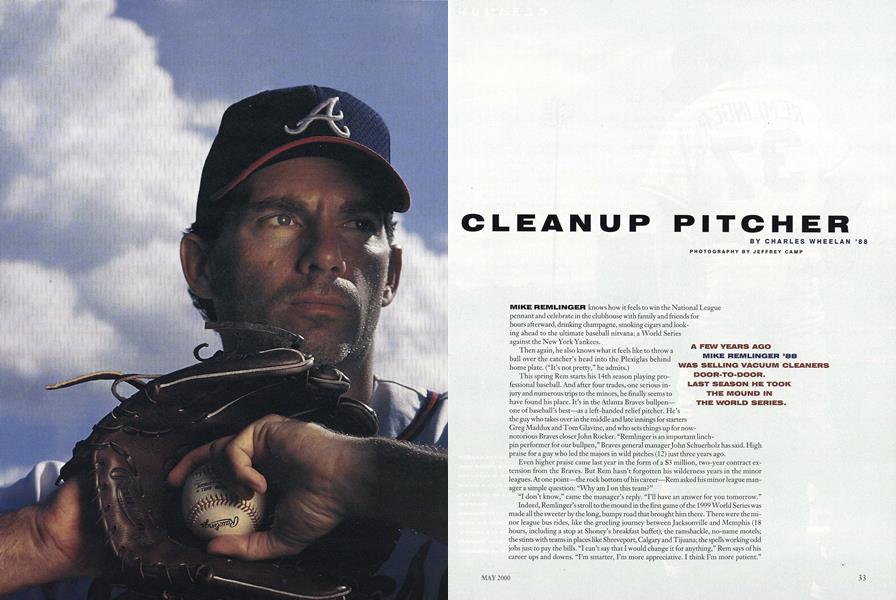

Cleanup Pitcher

A few years ago Mike Remlinger ’88 was selling vacuum cleaners door-to-door. Last season he took the mound in the World Series.

MAY 2000 Charles Wheelan ’88A few years ago Mike Remlinger ’88 was selling vacuum cleaners door-to-door. Last season he took the mound in the World Series.

MAY 2000 Charles Wheelan ’88MIKE REMLINGER knows how it feels to win the National League pennant and celebrate in the clubhouse with family and friends for hours afterward, drinking champagne, smoking cigars and looking ahead to the ultimate baseball nirvana: a World Series against the New York Yankees.

Then again, he also knows what it feels like to throw a ball over the catcher's head into the Plexiglas behind home plate. ("It's not pretty," he admits.)

This spring Rem starts his 14th season playing professional baseball. And after four trades, one serious injury and numerous trips to the minors, he finally seems to have found his place. It's in the Atlanta Braves bullpenone of baseball's best—as a left-handed relief pitcher. He's the guy who takes over in the middle and late innings for starters Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine, and who sets things up for nownotorious Braves closer John Rocker. "Remlinger is an important linchpin performer for our bullpen," Braves general manager John Schuerholz has said. High praise for a guy who led the majors in wild pitches (12) just three years ago.

Even higher praise came last year in the form of a $3 million, two-year contract extension from the Braves. But Rem hasn't forgotten his wilderness years in the minor leagues. At one point—the rock bottom of his career—Rem asked his minor league man- ager a simple question: "Why am I on this team?"

"I don't know," came the manager's reply. "I'll have an answer for you tomorrow."

Indeed, Remlinger's stroll to tie mound in the first game of the 1999 World Series was made all the sweeter by the long, bumpy road that brought him there. There were the minor league bus rides, like the grueling journey between Jacksonville and Memphis (18 hours, including a stop at Shoney's breakfast buffet); the ramshackle, no-name motels; the stints with teams in places like Shreveport, Calgary and Tijuana; the spells working odd jobs just to pay the bills. "I can't say that I would change it for anything," Rem says of his career ups and downs. "I'm smarter, I'm more appreciative. I think I'm more patient." And most important, he will never again have to sell vacuum cleaners door-to-door.

A left-hander recruited out of PlymouthCarver High School in Massachusetts, Remlinger did great things in a Big Green uniform. Fie was a hard thrower, says Mike Walsh, Rem's Dartmouth coach. But his greatest weakness, then and now, was control. "You knew he was going to hit you with about every fifth pitch, so as a batter you never wanted to dig in," says Bill Hanekamp, a fellow '88 Big Green teammate.

Remlinger went 22-12 in three seasons at Dartmouth, leading the team to its first Eastern Intercollegiate Baseball League championship in more than 25 years and then to the NCAA tournament, where he threw a four-hit shutout against Big 10 champion Michigan. In only three seasons, Remlinger set Dartmouth records for innings pitched (239), season strikeouts (132), career strikeouts (337) and career wins (22). By the spring of his junior year, Rem, fingered by Baseball America as the top left-hander available in the major league amateur draft, made the professional plunge. The San Francisco Giants picked him 16th in the first round of the 1987 draft. (He finished his Dartmouth economics degree in 1991 after returning to campus several times during his offseasons.)

Remlinger rocketed through the Giants organization, spending only five days in rookie ball and a month in single A. In one of his early appearances in AA, he struck out the first nine batters and threw a perfect game through seven innings before leaving the game to rest his arm. He finished his first professional season 6-3 with a 2.90 ERA.

But before making it to the majors, disaster struck. "The next spring I got hurt," Rem says. Looking back, doctors say his persistently sore elbow was probably a partially torn ligament, an injury that might be treated with surgery if it happened today. (Braves reliever Kerry Ligtenberg had such a procedure done last year.) But at the time, the Giants insisted that Rem not have surgery. Instead, the lefty embarked on a long stretch of uncertainty and frustration, sitting out the year to nurse his elbow.

"When I came back the following spring, I was nowhere near the pitcher I had been," he says. "I wanted to be what I was, or I didn't want to play. Sol struggled emotionally and psychologically a lot. Instead of being able to accept it, I fought it." Rem desperately tried to get his velocity back, but in the process he lost both his control and his confidence.

Still, he displayed flashes of brilliance. In June of 1991, Rem was called up to make his major league debut against Pittsburgh. He tossed a three-hit shutout win to become only the 37th pitcher in major league history to throw a shutout in his first major league appearance. But the minor leagues were just a few wild pitches away. The Giants traded Rem to Seattle at the end of the season, and the Mariners promptly shipped him off to play AAA ball in Calgary. There he began a slide toward the nadir of his career. "I was playing as bad as I could," he recalls. "I was playing for a manager who I absolutely hated, and he hated me. I hated going to the field every day. It wasn't fun." And neither were Rem's numbers. He went 1-7 in Calgary in 1992 with a 6.65 ERA. Even worse, he spent the off-season in Phoenix selling vacuum cleaners door-to-door to pay the bills.

Remlinger continued to tangle with the manager from hell, Calgary's Keith Bodie. "I was playing for a guy who saw me as a firstround draft pick who had had everything handed to him and wasn't that good. And he was right," says Rem. "He took every opportunity he had to stick it in my face and basically screw me."

For the first time, Remlinger contemplated life without baseball. After one of their frequent tangles, Bodie asked the pitcher if he wanted his release. "Well, no," Rem replied. "What am I going to do?" But several months later, Bodie asked again if he wanted to be released, Rem was ready. "Yeah," he shot back. "You're sitting there telling me I suck. You don't know when I'll play again. What am I on your team for?"

In the end, Remlinger wasn't released. ("Evidently someone in this organization still thinks you can pitch," Bodie told him.) Instead, Rem headed to the AA team in Jacksonville, a demotion for which he was eternally grateful. No more cold Canada. "I'm going to the beach," thought Rem, "and I'm leaving you."

A silver lining of the two-year Calgary stretch was that Rem met Ronelle Shedd through a mutual friend. They were married in October of 1993 before moving back to Plymouth for the winer to be near Remlinger's ailing father. Like most professional players struggling to play in the big leagues, he had signed two contracts, one that pledged a certain salary if he were called up to the majors, and one that promised a lot less money—about $5,000 a month for the six-month season—while he was playing in the minors. So only a few months before his Dartmouth Fifth Reunion, Rem found himself shoveling snow and working construction during the day and then trudging to the gym for several hours every evening to work out—a combination that eventually became debilitating. "I'd wake up cold at night, and I couldn't even pull the covers up because I couldn't unbend my hands," he says. "I'd have to wake up in the mornings and just soak my hands under hot water to get them to open up."

The spring of 1994 brought two changes. One was a Mets uniform: Rem had become a minor league free agent and New York picked up his contract. The second transformation took place inside Remlinger's head. "I gave up trying to be what I had been and just tried to be what I could be," he explains. He would settle for "throwing darts"—pitching slower but with better control. The new approach worked. Rem climbed back to the majors for the first time since 1991 and felt like he was pitching consistently well for two months. Then, as if the baseball gods were conspiring against him, the players went on strike. He headed south to play ball in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. It was there—in a single pitch—that Mike Remlinger got his fastball back. "It came out and jumped," he recalls. "That was the way I had always pitched up until I got hurt. I went from throwing probably 85-86 miles an hour to throwing 90-91 again, in one pitch."

The spring of 1995 required yet another change-of-address card. This time the mail would be forwarded to Cincinnati; the Reds swapped a little-known outfielder, Cobi Cradle, for Remlinger. Before the trade, Rem and his wife spent exactly one night together in the new house they had found in New York. The deal left them stuck with several months' rent and assorted deposits.

In Cincinnati Remlinger did his best to impress the Reds, and that became perhaps his worst problem. "Now instead of being happy throwing 90-92 [mph], I wanted to throw 100-102," he says. "I was juiced up and I wanted to prove to everybody that I was the best thing they'd ever seen and I deserved to be here." He wasn't, and he didn't. Rem spent the next two years shuttling between the majors and the minors, learning quickly that the worst words you can hear as a marginal major league player are "The manager wants to talk to you."

In 1997 Remlinger made the Reds' major league roster out of spring training and saw his salary jump to $300,000. While he would never again see the inside of a minor league bus, the Cincinnati years were quintessential Remlinger: raw talent overshadowed by control problems. In the last game of the 1997 season against the Montreal Expos, Rem retired 20 straight batters before a two-out double by Jose Vidro bounced off left fielder Mike Kelly's glove and broke up the perfect game. The same year he led the majors in wild pitches.

The Reds held on to Remlinger for another year, but he was not getting the job done as a starter. Still, baseball economics being what they are, his market value rose to $1.1 million at the end of the 1998 season, making Rem too expensive to keep. So the Reds sent the pitcher and Ail-Star second baseman Bret Boone to Atlanta last spring in exchange for pitcher Denny Neagle, outfielder Michael Tucker and minor league pitcher Rob Bell. Boone and Neagle were the big names in the trade, but Rem was more than a footnote. Indeed, he was a perfect fit for the Braves. Atlanta scouts had seen promise in Remlinger, who had allowed only 16 percent of inherited runners to score—third best in the National League. The Braves needed a lefty reliever and, as a major market team, they could afford him.

The remarkable depth and talent in the Braves bullpen offered two immediate benefits. First, Rem could learn from a playoff-seasoned pitching staff that included some of the starters he used to study on videotape. Second, and perhaps more important, he would not be in a position to push himself to do too much. Rem made clear to manager Bobby Cox and pitching coach Leo Mazzone—both of whom offered an upbeat, relaxed, encouraging style of leadership—that he was there to do whatever was asked of him, whether that meant throwing three pitches in a game or three innings.

Perhaps best of all, Rem's sore shoulder responded well to a shot of cortisone, enabling him to throw pain-free for the first time in five years. "You take all those things and roll them into one big ball, and that's why I was able to do what I did last year," he says.

By mid-June Rem had made 28 appearances and was the only Atlanta pitcher with an ERA under 2.00. "For a guy who'd been dubbed a pitcher with control problems, Remlinger has done a good job of hiding it," declared the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. From there, the season just got better. Remlinger did not lose a regular season game after May. In August he went 4-0, appearing in 14 games and throwing 17 1/3 perfect innings. He finished the regular season 101 (the most wins for a Braves reliever since 1971) with 2.37 ERA in 73 appearances.

Rem carried that momentum into the playoffs, making two appearances in the series against Houston and five against the Mets in the National League Championship Series. The crowning achievement came in game six, when Rem pitched 12/3 innings (giving up one earned run) en route to an 11th-inning Braves win to take the National League pennant. "This is what you've been dreaming about since you were a little kid, playing in your backyard growing up—going to the World Series," Remlinger recalls.

The World Series would prove a disappointment, both for Remlinger and the Braves. The Yankees swept the series in four games, and Rem gave up a game-winning home run to Chad Curtis in the 10th inning of game three. Rem, who is so competitive that he sometimes finds himself racing his wife to the refrigerator, remembers the pain of falling behind the Yankees overshadowing the excitement of being in the World Series. "I'm not pitching in the World Series," he remembers thinking. "I'm pitching in a game we're losing."

It is a bump he has since shrugged off. "It was Christmas all year for me," he reflects. "From the day I signed my contract, to the day I started the season wearing.an Atlanta Braves uniform, to the day I stood on the mound in the World Series—even when we lost." It is not a surprising comment from someone who talks a great deal about staying grounded. "I think the biggest thing is just appreciating what you have," he says.

Christmas might extend into this fall for the Remlingers. Thanks to that new contract, Rem, Ronelle and their 21-month-old son Chance have settled comfortably in a six-bedroom house outside Atlanta. And though the season has only just begun, Rem looks forward to making his contribution to the highly touted Braves as they gun for another World Series—and a chance to win it all.

AS THE SEASON GETS UNDER WAY, REM IS EXPECTED TO PLAY A MAJOR ROLE IN ATLANTA'S BULLPEN. PHOTOGRAPHED FEBRUARY 24, 2000 AT THE BRAVES' SPRING TRAINING CAMP IN ORLANDO.

FROM DARTMOUTH...

...TO BUSH LEAGUES...

...TO BIG LEAGUES...

...TO THE WORLD SERIES.

A FEW YEARS AGOMIKE REMLINGER '88WAS SELLING VACUUM CLEANERSLAST SEASON HE TOOKTHE MOUND INTHE WORLD SERIES.

REM ASKED HIS MINORLEAGUE MANAGERA SIMPLE QUESTION:"WHY AM I ON THIS TEAM?""I DON'T KNOW,"CAME THE MANAGER'SREPLY. "I'LL HAVEAN ANSWER FORYOU TOMORROW."

"THIS IS WHAT YOU'VE BEEN DREAMING ABOUT SINCE YOU WERE A LITTLE KID—GOING TO THE WORLD SERIES."

CHARLES WHEELAN is the Midwest correspondent for The Economist. He lives in Chicago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

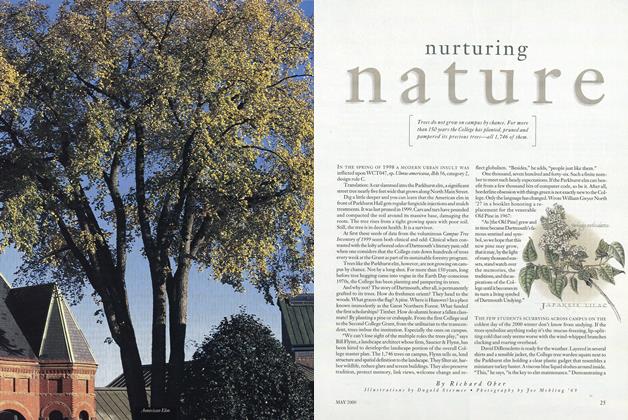

Cover StoryNurturing Nature

May 2000 By Richard Ober -

Feature

FeatureLive From New York!

May 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Private Lives of Public People

May 2000 By Jennifer Avellino ’89 -

SYLLABUS

SYLLABUSScreening Reality

May 2000 By Kathleen Burge ’89 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Excellence

May 2000 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleYou Are Here

May 2000 By Noel Perrin

Features

-

Feature

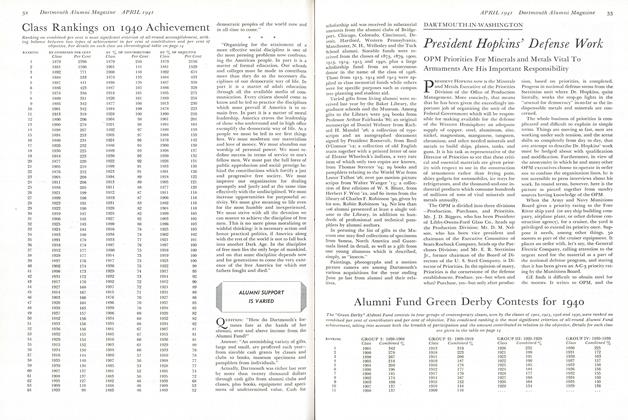

FeatureAlumni Fund Green Derby Contests for 1940

April 1941 -

Feature

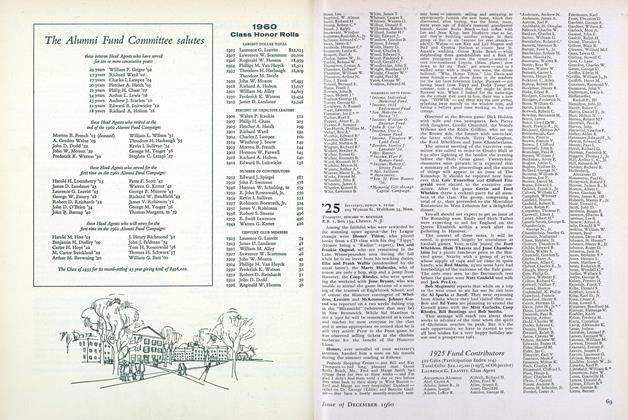

Feature1960 Class Honor Rolls

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureBetting man's choice: Dartmouth. Then Harvard, Columbia, Cornell

OCTOBER 1972 -

Feature

Feature"What We Are After"

May 1960 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Feature

FeatureA CITY VOICE CRYING IN THE WILDERNESS

JUNE 1963 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Feature

Feature"Ladieees and Gentlemen.

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Jim Tonkovich '68