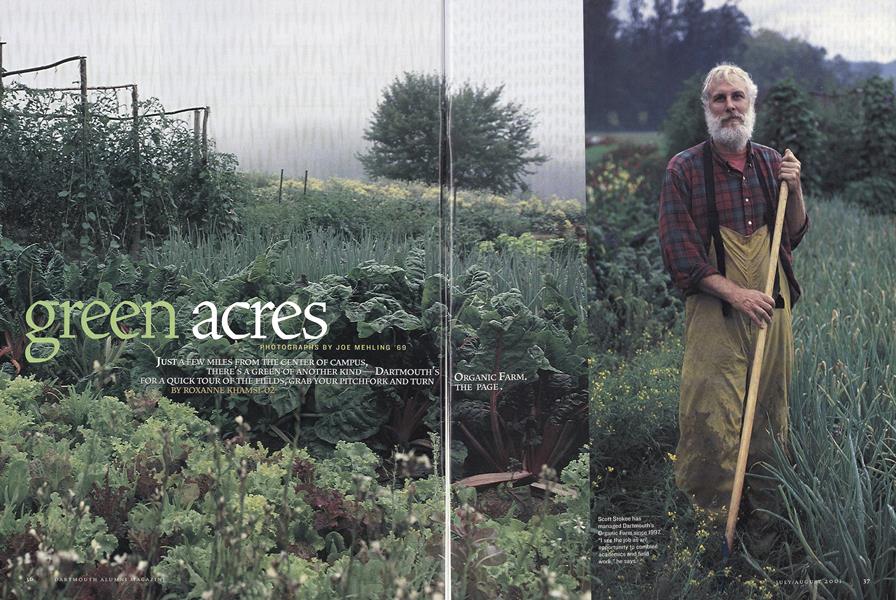

Green Acres

Just a few miles from the center of campus, there’s green of another kind.

July/August 2001 ROXANNE KHAMST ’02Just a few miles from the center of campus, there’s green of another kind.

July/August 2001 ROXANNE KHAMST ’02Just a few miles from the center of campus, there's green of another kind-Dartmouth's organic farm. for a quick tour of the fields, grab your pitchfork and turn the page.

The farm is a grassroots protect.

The idea of establishing an organic farm at the College came from students involved in an upper-level environmental studies course ("Environmental Problem Analysis and Policy Formation") in 1988. As part of an assignment to explore ways in which Dartmouth could become more environmentally sustainable, they produced a report titled "Reduce, Reuse, and Educate: A Solid Waste Management Program at Dart- mouth." Seven years later the report inspired a new set of students to ask the administration to support an organic farm. It did. The College opened the farm in 1996 and gave it three years to prove itself. Five years later the farm has grown into a permanent program under the Outdoor Programs Office. Since its opening the farm's role as a site for both academic innovation and social opportunity has broadened. Here's a sampling:

1. No green thumb is required.

Many students who participate in farm activities had little experience with agriculture before coming to the College. "I'm from the city. I'd never even gardened before," says Katy Tooke '02, a native of Boston who is one of the farm's more active students. "As I've gotten more involved, I've gone from a volunteer who is told what to do to someone who's involved in the decision-making process." While participating as a farm intern, Tooke helped order seeds, plan the crop rotation and coordinate vollunteers' schedules. And through the engineering department she arranged an independent-study project to explore designs for a new greenhouse at the farm. The greenhouse would rely on solar energy, reducing the need for fossil-fuels in colder weather. Using a computer program to integrate weather data gathered from the College s photovoltaic center, Tooke compared different parameters of her greenhouse model to see which dimensions would minimize energy needs.

2. It's even certified.

The two-acre farm undergoes annual certification by the New Hampshire Department of Agriculture to ensure that the agricultural practices in the fields and in the greenhouse comply with standardized organic methods, which means synthetic fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides are a no-no.

3. Like many small farms, practice means more than profit.

While original plans called for the Organic Farm to be self-supporting, that's not possible on only two acres. The College subsidizes the farm—the annual operating budget is approximately $50,000—because it is viewed as an important program for undergraduates. Student farmers do sell vegetables, fruits and flowers at a weekly produce stand they operate outside of Collis student center. The farm also sells produce to Dartmouth Dining Services, the Hanover Inn and the Ravine Lodge. But veggie sales don't cover the cost of production, even with free labor. During the summer, farm days begin at 7 a.m., when students join Stokoe in harvesting, washing and boxing crops such as broccoli, snap peas and several varieties of lettuce for the cafeterias. "We raise less than one-tenth of our budget from our produce," says Stokoe. "Our goal is not to be a producing farm. Our goal is to contribute to the education and development of our students."

4. Students can live on the farm.

The College owns a house on the farm, which overlooks the fields and Connecticut River about three miles north of campus. Each term three students live there in return for $975 and a commitment to work at least six hours a week on the farm. "Farming requires that you live with the environment and watch the crops closely—its a 24-hour activity," says Emily Neuman '99, who, since graduation, has gone on to work at several other organic farms.

5. Fields make great classrooms.

Dartmouth professors take advantage of what the farm has to offer. Last summer professor Ross Virginia held the laboratory portion of his ecological agriculture course there. Students in his class carried out an experiment to determine whether the intercropping of broccoli and lettuce produced a yield advantage. During the first few labs, students carefully hand-weeded their crops and learned how to measure soil moisture levels. They later analyzed weekly measurements of leaf size and plant height as well as nitrogen levels in the soil. Professor David Peart brings his "Biological Diversity" class to the farm several times each summer to survey the wide range of species present in an agricultural site. "It is important to understand how human-managed systems impact biological diversity" says Peart. Some of his students choose to conduct their final projects at the farm (surveying the insects in the field, for example). But not every class that heads to the farm has a scientific spin. Professors who teach nature writing and religion courses also use the farm to put land cultivation in context and provide the opportunity for spiritual connection with the outdoors.

6. Some of the projects are, well, nutty.

Students going on the environmental studies foreign study program in Africa gain a better understanding of the crops they will encounter during their term abroad. In a far corner of the field, by the river, the distinctive leaves of a tobacco plant soak up sunshine. In an adjacent plot the delicate stems of a peanut plant struggle with the relatively cool Northeastern climate. Elsewhere there's cotton, sorghum and millet, all staple crops in the region of Africa where students will be studying.

7. Things can get quite hot- in the compost pile.

Stick around the Organic Farm long enough, and you're bound to hear talk about "closing the loop"—code for reducing waste through recycling. The farm makes its own compost from plant debris as well as kitchen scraps from the house. Students hand machete fresh green matter from the field, such as bolted lettuce and broccoli plants, to create a compost pile 5 feet tall with a 25 square-foot base. Microorganisms do the hard work, slowly converting the waste back into nutrient-rich organic matter for later use in potting mix and field fertilizer. The process heats the pile to sweltering internal temperatures of between 140 and 150 degree Fahrenheit.

8. Even the manure is green.

Organic farmers use many tricks to enrich soil without man made fertilizers. One nifty technique involves "green manure tilling a cover crop back into the soil to add organic matter. Last year students undersowed soybeans beneath crops of sweet corn and white clover. The experiment yielded more than ears of corn. It showed that nurturing a sustainable earth means going back to its roots.

Scott Stokoe has managed Dartmouth's Organic Farm since 1997. "I see the job as an opportunity to combine academics and field work," he says.

Student volunteers assist with planting and harvesting—and selling the produce at the Collis market.

Roxanne Khamsi is a biology major from Brookline, Massachussetts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

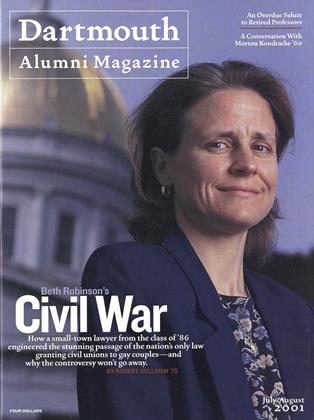

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Civil Action

July | August 2001 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of Emeritus

July | August 2001 By Jay Parini -

Feature

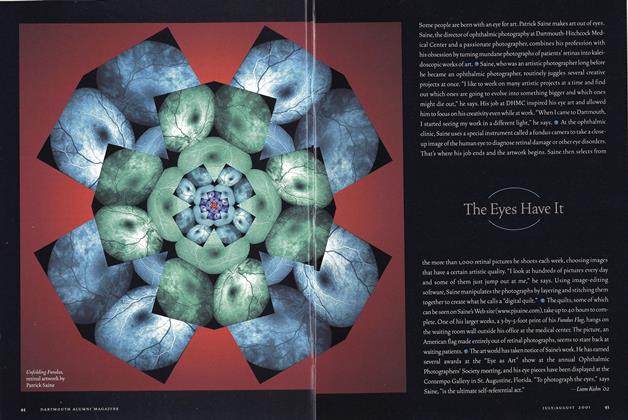

FeatureThe Eyes Have It

July | August 2001 By Liam Kuhn ’02 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July | August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYA Breed Apart

July | August 2001 By Marcus Coe ’00 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

July | August 2001

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobert Harris Upham 1832

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureEvaluating Kitsch

November 1982 By Alan Gaylord -

Feature

FeatureA World of Difference

May/June 2009 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’04 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2008 By John Kemp Lee '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GET YOUR NAME INTO THE GUINNESS BOOK OF WORLD RECORDS

Jan/Feb 2009 By LARRY OLMSTED, MALS '06 -

Feature

FeatureAre Marriage and College Compatible?

March 1960 By MARGARET MEAD