Water Under Fire

There’s arsenic in America’s drinking water. A toxicologist measures the debate about how little is too much.

July/August 2001 Joshua HamiltonThere’s arsenic in America’s drinking water. A toxicologist measures the debate about how little is too much.

July/August 2001 Joshua HamiltonThere's arsenic in America's drinking water. A toxicologist measures the debate about how little is too much.

IN MARCH THE ENVIRONMENTAL Protection Agency (EPA), under its new Bush-appointed director, Christie Todd Whitman, revoked a law signed by President Bill Clinton in January that would have lowered the allowable standard for arsenic in United States drinking water from 50 parts per billion (ppb) to 10 ppb. The 50 ppb standard, which has been in place since 1942, is associated with risks to human health.

The move immediately pitted Whit- man and President Bush against environmentalists. Initially accusing Clinton of rushing through the new standard at the last minute/Whitman and Bush contended that there was still considerable scientific controversy about what should be an appropriate standard for the level of arsenic in drinking water. Critics, such as the Natural Resources Defense Council and other environmental groups, responded that there was indeed convincing evidence that the current level was putting people at risk of cancer and other diseases. Subsequently, Bush said his principal concern was that there had not been sufficient cost-benefit analysis in setting the new standard—estimated to cost up to $5 billion in capital investments alone if instituted nationwide.

The arsenic debate typifies the way controversies over environmental health risks proceed in our society. Often these debates are turned back to scientists, who are expected to deliver definitive answers. But science by its very nature always involves a level of uncertainty, and finding answers through research can be a slow process. Scientific uncertainty can become a political tool used to support different sides of an issue. It is instructive, then, to examine the current arsenic debate to see what we know, and what we do not know, about arsenic and its impact on public health.

The Bush administrations statement that Clinton had rushed the new standard through at the last minute is clearly inaccurate. The EPA has been working on a new arsenic standard for more than a decade. (Most of the Western world has had an arsenic drinking water standard of 10 ppb for years, and the World Health Organization has proposed 10 ppb as a worldwide standard.) In 1996 the EPA asked the National Research Council (NRC), an independent scientific review group within the National Academy of Sciences, to review the arsenic standard and make recommendations to the EPA. The 1999 NRC report urged the EPA to immediately lower the allowable level, and suggested a range of between 5 and 10 ppb. Based on this report and its own independent evaluation, the EPA recommended a new arsenic standard of 5 ppb in January 2000. After feedback from Congress, industry, private advocacy groups and the public, that recommendation was revised upward to 10 ppb in January 2001. This is the regulation Clinton signed before leaving office.

The question of whether there is definitive evidence for a particular arsenic standard is more complicated. There is virtually universal consensus within the arsenic research community that 50 ppb is too high. The NRC review of epidemiology studies from various parts of the world where people drink arsenic-laden water found that 50 ppb was at or close to the level at which there are measurable health effects.These include increased incidences of blood vessel and heart disease, type 2 diabetes and various types of cancer.

Other independent studies have reached similar conclusions. An epidemiology team headed by Margaret Karagas from Dartmouth's Toxic Metals Research Program recently reported a doubling of the skin cancer risk for people exposed to arsenic at 50 ppb and higher in New Hampshire. My own laboratory group recently demonstrated that at concentrations equivalent to drinking water levels of 50 ppb to as low as 5 ppb, arsenic can act as a potent endocrine disruptor in cultured animal cells. The glucocorticoid receptor that arsenic disrupts plays a role in suppressing cancer, regulating blood sugar and maintaining blood vessel function.

If 50 ppb is too high, how low should we go with the new standard? Here is where scientific uncertainty kicks in, and where we must begin to make societal and cost-benefit decisions. We do not have direct evidence for or against human health effects at doses below 50 ppb, but can only estimate them based on various mathematical models. We also do not know whether arsenics toxic effects only kick in above a certain "threshold" dose or whether the effects are 'directly proportional to dose even at very low doses, so we must make certain assumptions in the absence of data.

Typically, either doubling or halving the dose of a chemical has only a small effect on the toxic effects of that chemical. Since 50 ppb of arsenic causes measurable health effects, we would prudently want to decrease the level to well below 20-25 ppb. On the other hand, there is no point in reducing the standard to 3 ppb or below, since the technology available to most small municipal water systems can only detect arsenic above that level.

It is not surprising then that the EPA ended up considering a new range of between 5 and 10 ppb as being both achievable and yet still allowing a margin of safety for protecting human health. The primary reason the EPA's initial recommendation of 5 ppb was adjusted upward to 10 ppb during last years comment period was an economic consideration—it is almost twice as expensive to meet the 5 ppb standard as it would be to meet 10 ppb, and we currently have no scientific information to suggest that 5 ppb will necessarily be more protective than 10 ppb.

This is where another level of uncertainty kicks in, for ultimately science can only provide us with probabilities, not certainties. It is important to understand that statistical pronouncements, such as, 'At 3 ppb, there will be 1 in 1,600 excess cancer deaths from arsenic," are only mathematical predictions.These are the possible effects of low doses of arsenic, based on what we know about the effects of high doses. The EPA and most others calculating low-dose risks use the most conservative mathematical models and assumptions; the actual risk is likely to be lower, maybe even zero.

So what is the right number, and how do we decide? Once we have factored in what we know about health effects at the high end and what we know about technological limitations at the low end, setting the actual number comes down to societal judgments—what is reasonable, and what we can afford. How do we balance equally legitimate economic and human health concerns in an environment of competing societal needs and finite resources? We will never have "definitive" scientific answers regarding arsenic or any other complex environmental problem, and the final regulatory decision is ultimately a collective societal decision, not a purely scientific one.

However, it is important that we base regulatory decisions on the best available data on hand, then review and revise them as new data come to light. In this case there is growing evidence that arsenic is contributing to human disease at the current national drinking water level of 50 ppb. Most scientists agree that we need to lower the standard.

It is completely legitimate—in fact, valuable and necessary in a democratic society-to evaluate the cost-benefit impact of such regulatory decisions. Based on what we know about arsenics health effects and the various practical and financial considerations involved, I believe that the EPA's previous recommendation of 10 ppb is a prudent and achievable arsenic standard.

Yes, the dollar cost of meeting the new standard is not small, and the cost is disproportionately distributed to certain geographic (and political) regions. But so are the human health costs, both in terms of the societal costs of arsenic-related illnesses and the dollar costs of those illnesses on individuals.and on our society. And while the cost of remediation is known, we are only now beginning to glimpse the human health impact of arsenic in the United States. I think we are seeing the tip of the iceberg. It will take five to 10 years to fully implement a new standard. It is time to act now.

Time to Act Professor Hamiltonsays arsenic standards rescinded bythe Bush administration are "prudentand achievable."

Joshua Hamilton, an associate professorof pharmacology and toxicology at DartmouthMedical School, is director of Dartmouth's Centerfor Environmental Health Sciences.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

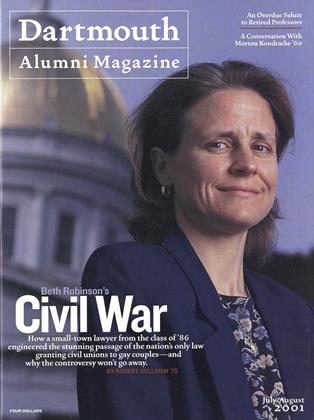

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Civil Action

July | August 2001 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of Emeritus

July | August 2001 By Jay Parini -

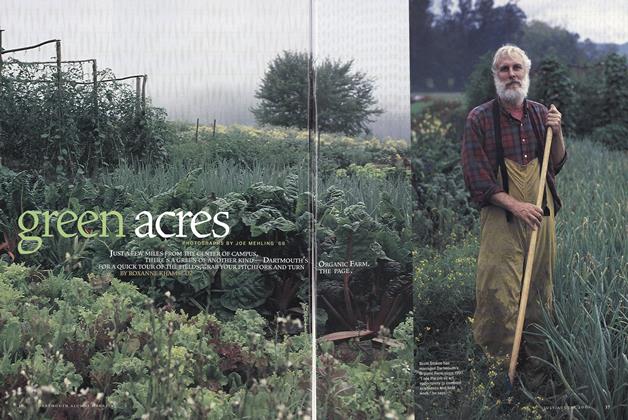

Feature

FeatureGreen Acres

July | August 2001 By ROXANNE KHAMST ’02 -

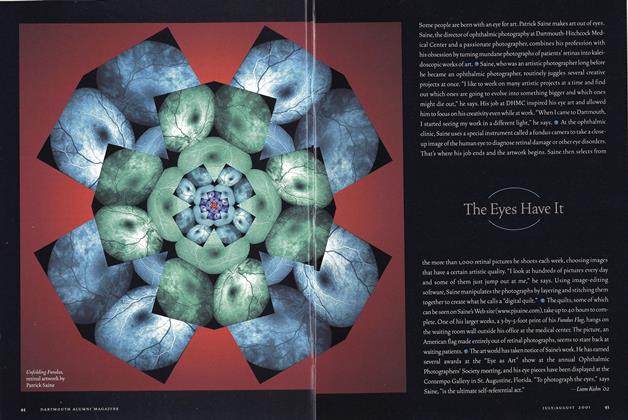

Feature

FeatureThe Eyes Have It

July | August 2001 By Liam Kuhn ’02 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYA Breed Apart

July | August 2001 By Marcus Coe ’00 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

July | August 2001

Faculty Opinion

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMillennial Mindset

May/June 2007 By Aine Donovan -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONLive Free or Die?

Jan/Feb 2009 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONThe Perils of Innovation

Nov/Dec 2010 By Chris Trimble and Vijay Govindarajan -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONEggheads vs. Meatheads?

Nov/Dec 2005 By DAVID KANG AND ALLAN STAM -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSlow Medicine

May/June 2009 By Dennis McCullough, M.D. -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONI Read, Therefore I Think

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2016 By DEVIN SINGH