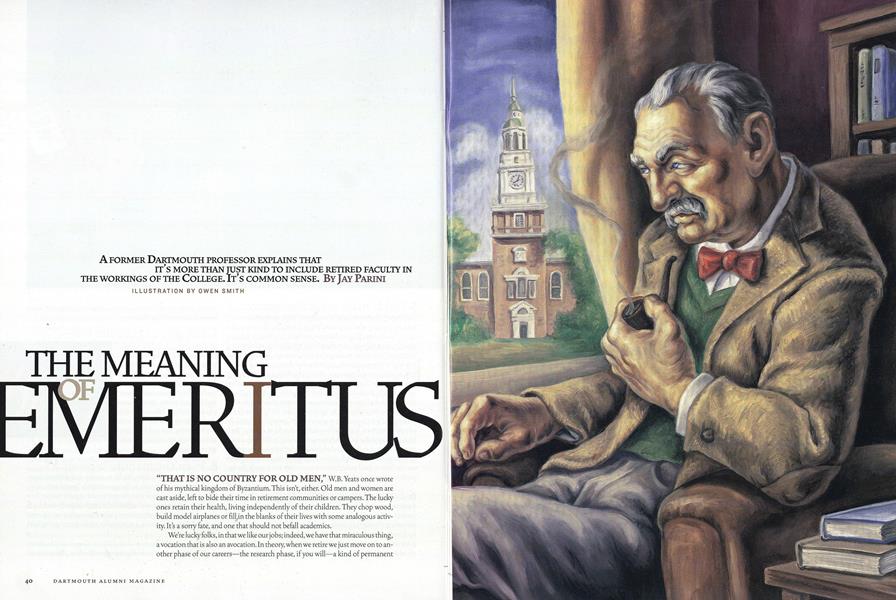

The Meaning of Emeritus

A former Dartmouth professor explains that it’s more than just kind to include retired faculty in the workings of the College. It’s common sense.

July/August 2001 Jay PariniA former Dartmouth professor explains that it’s more than just kind to include retired faculty in the workings of the College. It’s common sense.

July/August 2001 Jay PariniA former dartmouth professor explains that it's more than just kind to include retired faculty in the workings of the College. It's common sense.

"THAT IS NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN," W.B. Yeats once wrote of his mythical kingdom of Byzantium. This isn't, either. Old men and women are cast aside, left to bide their time in retirement communities or campers. The lucky ones retain their health, living independently of their children. They chop wood, build model airplanes or fill in the blanks of their lives with some analogous activity. It's a sorry fate, and one that should not befall academics.

We're lucky folks, in that we like our jobs; indeed, we have that miraculous thing, avocation that is also an avocation. In theory, when we retire we just move on to another phase of our careers—the research phase, if you will—a kind of permanent Guggenheim leading up to those golden, open stacks in heaven. The problem is that it rarely turns out that way.

In 30 years of teaching, I've become attached to many older colleagues, only to see them disappear after their final graduation, the dubious badge of emeritus pinned to their gowns. But there is no merit in emeritus, not in most U.S. colleges or universities. Emeritus means goodbye, hasta la vista. The familiar faces are suddenly absent from department meetings. The retired no longer pace the hallway, answer the phone or offer candid words of advice. Students forget their names. Former colleagues barely seem to recall their presence. Then younger colleagues come on board, and they've never even heard of Professor So-and-So, once so popular with students and famous in the field.

If one catches sight of an emeritus professor, in the library or at some concert, one merely gives a furtive, rather guilty, nod. "You should be dead by now," we seem to say. And that's despicable.

That emeritus faculty members can play a crucial role in the lives of younger colleagues was made evident to me when I was a young English instructor. My first teaching job was at Dartmouth, where, during my first term, a retired professor named Maurice Quinlan stopped by my office in Sanborn House. Maury was a friend of a friend, and he had once taught at Dartmouth—40 years or so before me. He'd moved around a lot, ending his career at Boston College. He was a distinguished teacher and the author of several well-regarded books on 18th-century literature. After retiring he'd taken up residence in a small house in the Hanover area, having had fond memories of his early days of teaching there. He used the Dartmouth library most days, working on scholarly projects to the end. A lifelong bachelor, he retained a lively wit and immense geniality into his 80s.

We became good friends, and I found myself increasingly eager for his guidance. I would take my syllabus to him before each term began, and he always gave me first-class advice. He knew what worked and what didn't. Once I revised a syllabus three times under his direction—much to the benefit of my students. Maury sat in on several of my classes, offering a kind of benign critique; I had nothing at stake, except excellence. He was never going to vote on my tenure. He wasn't going to put in any official word on my behalf. He offered mentoring, in the purest sense.

In several moments of intense personal anxiety—when, for example, I was coming up for tenure—I sought Maury out in something like desperation. He was invariably kind, wise and stern. "If a college doesn't want to give you tenure, it's not a college where in the long run—you would be happy to teach," I recall him saying. The severity of his approach was essential: He had experienced versions of my situation, and he seemed to know exactly what I should do. You can't buy that kind of counsel.

I had been to see Maury only a few weeks before he died. I had brought him a manuscript of an article I was writing, and—in his typically generous manner—he had marked it up. "I'm afraid I've scratched a lot out," he said. That was an understatement. He'd scratched out most of it, and most of it deserved scratching out. But the parts that remained were underlined, with "good" in the margins. In several places he had written "develop" or "expand." I knew instinctively what he meant by those cryptic commands, since we'd had enough conversations leading up to them. The pity was that they couldn't continue.

My point should be obvious by now. The retired professor holds a great treasure: experience. It's the kind of thing that only trial and error can produce. The wisdom and institutional memory that old heads carry are desperately needed by younger faculty members, who should not have to continuously reinvent the wheel. Forgeting is the easiest thing in the world to do, and the hardest to recover from. So it's not mere kindness to "include" emeriti in the workings of an institution. It's common sense.

I recently spent a year as a visiting fellow at Christ Church college at Oxford University, and I was struck by the wisdom of the British attitude toward retired faculty members. The difference between those "on staff" and those "formerly on staff" seemed slight. Retired fellows still came to lunch and were fully conversant with the politics of the college, with teaching issues and with the scholarship of their younger colleagues, which they seemed ready and willing to discuss. They had pride of place at the high table in the main hall each evening.

One of my favorite colleagues was a retired scientist, a lovely man in his late 70s, who spent all day in the laboratory at the university and rarely missed a meal in the dining hall. He still informally helped graduate students, as needed, and taught the occasional seminar in biochemistry. He traveled the world to attend conferences. He was working on several important projects. He still is, as far as I know.

I don't see why such a model couldn't work in American institutions, and alumni might even enjoy subsidizing the cost, since we are talking about their former teachers. Scientists should retain full access to labs and research facilities. All retired professors should, if they wished, retain an office in their former department, not in some game preserve on the edge of campus for hoary-headed creatures. They should have access to the same secretarial help and professional-development funds that were always available to them. They should be invited to attend faculty and department meetings, be encouraged to teach regularly, and be asked to advise students (either formally or informally, depending on their wishes) in their special areas of interest. More to the point, they should be respected for what they are: honored citizens in a community of scholars.

Many retired professors would, undoubtedly, choose separating and forgetting, preferring to retreat to southern Florida and occupy themselves with golf and casual reading. They might well hesitate to assume duties without the level of remuneration to which they had grown accustomed—or they might simply worry about being a nuisance.

But that scenario might we'll change over time. The energy for effecting this change would have to come from both sides of the retirement line—from institutions, which would make the appropriate gestures, and from emeritus faculty members, who would make the appropriate recommitments to scholarship and (necessarily to a lesser degree) to teaching.

I'm sure that many younger faculty members would cringe at the thought of Professor X stomping up and down the hallways again—that's perfectly human. But the cult of youth has, in some ways, damaged the academy.

Especially in the humanities, excellence in scholarship often demands decades of preparation and immense patience. Young scholars in search of tenure and grants are too often encouraged to publish immature work—work naively absorbed in whatever passing approach and accompanying jargon happen to be fashionable. The ancient symbol of the revered, old scholar, full of wisdom and years, with a shrewd, ironic, generous perspective that could improve the field, seems lost.

I deeply admired an elderly professor who taught me at Lafayette College in the 19605. He was then nearly 70, having been spared retirement at 65 by an institution that respected his unique wisdom and abilities. His name—he died well over a decade ago—was W. Edward Brown, and he taught classics and comparative literature. More than anyone else I've ever known, he was steeped in European literature, from ancient Greece and Rome through the 20th century. He read closely, in their original languages, the great French and Russian novelists of the 19th century. He could locate a passage by Dante, in Italian, in a few moments. He had translated some of Rilkes most difficult poems, and he knew scenes from Goethe's Faust by heart. During the years when he was teaching, he published very little indeed, he'd probably not get tenure today. However, when he finally retired, he devoted himself to a final, fruitful decade of writing publishing several monumental works on Russian literature that revealed a well-tempered mind seasoned by decades of reading and deepened by experience.

One can, of course, overestimate the benefits of age, which may serve only to confirm prejudice and harden bad habits. But genuine wisdom necessarily involves a refining process that takes time. I've talked to enough retired professors to know that what they have to offer is valuable beyond calculation. The system, as it's currently set up, does not encourage faculty members to grow and develop beyond the age of retirement. The few who buck the system, who thrive as scholars beyond their last day in the classroom, are exemplary. We should emulate them, revere them and encourage our institutions to put in place the structural, financial and emotional supports that would encourage everyone to see—really to see—that emeritus status is a goal worth aiming for.

THE RETIRED PROFESSOR HOLDS A GREAT TREASURE: EXPERIENCE IT'S THE KIND OF THING THAT ONLY TRIAL AND ERROR CAN PRODUCE.

Jay Parini is a poet, novelist and professor of English at Middlebury CollegeHe taught English at Dartmouth from 1975 to 1982. His most recentbook is Robert Frost: A Life (Henry Holt, 1999).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

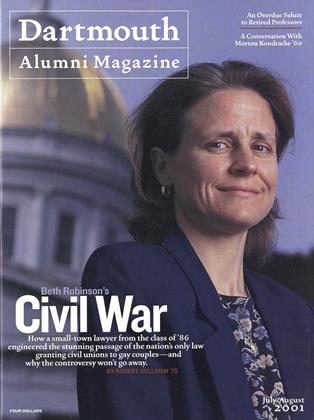

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Civil Action

July | August 2001 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

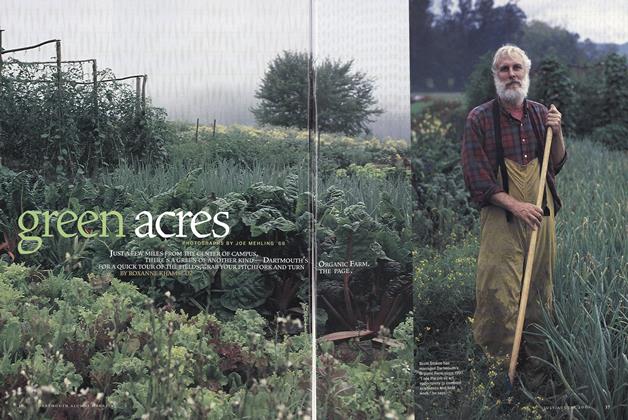

Feature

FeatureGreen Acres

July | August 2001 By ROXANNE KHAMST ’02 -

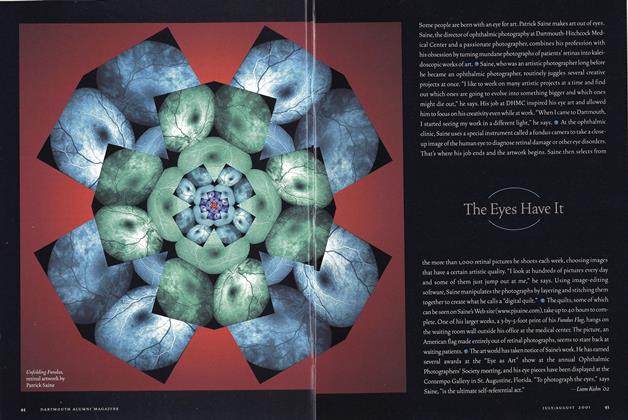

Feature

FeatureThe Eyes Have It

July | August 2001 By Liam Kuhn ’02 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July | August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYA Breed Apart

July | August 2001 By Marcus Coe ’00 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

July | August 2001

Jay Parini

-

Feature

FeatureRichard Eberhart at Eighty: The Long Reach of Talent

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Jay Parini -

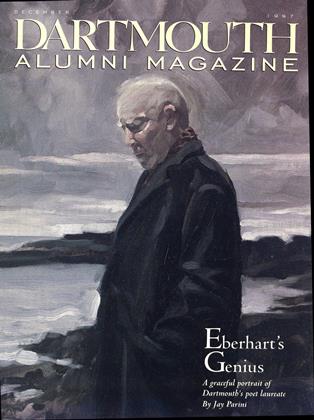

Front Cover

Front CoverFront Cover

DECEMBER 1997 By Jay Parini -

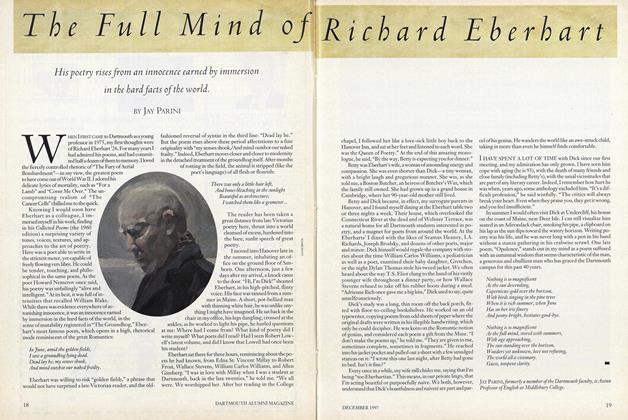

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Full Mind of Richard Eberhart

DECEMBER 1997 By Jay Parini -

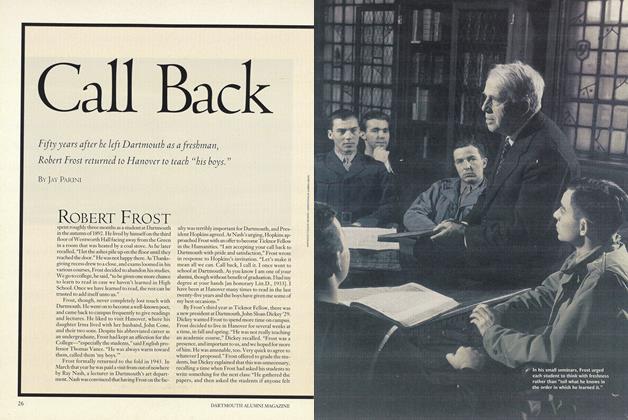

Feature

FeatureCall Back

May 1998 By Jay Parini -

Feature

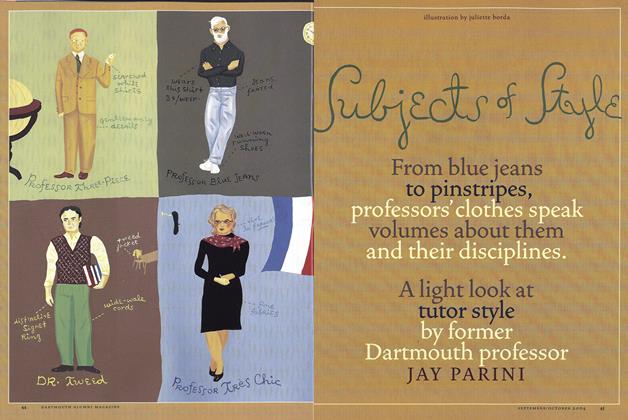

FeatureSubjects of Style

Sept/Oct 2004 By JAY PARINI

Features

-

Feature

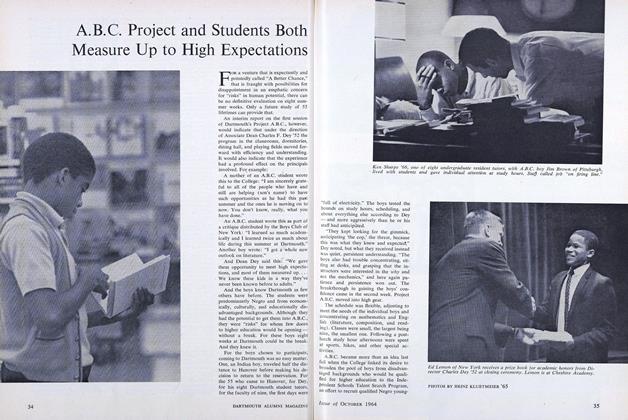

FeatureA.B.C. Project and Students Both Measure Up to High Expectations

OCTOBER 1964 -

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Year Begins June 14

JUNE 1969 -

Feature

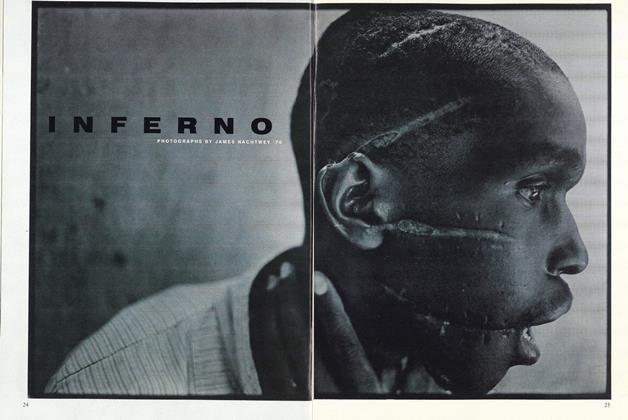

FeatureInferno

JUNE 2000 -

Feature

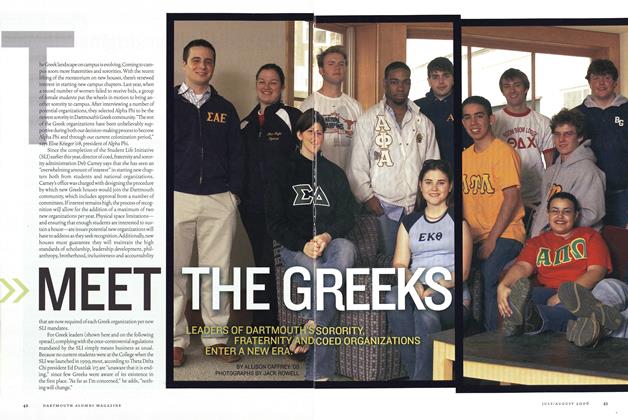

FeatureMeet the Greeks

July/August 2006 By ALLISON CAFFREY ’06 -

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

NOVEMBER 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGeared for Success

OCTOBER 1984 By Jim Kenyon