Quote/unquote "Robert Reich's essay is based on the faulty premise that going to a selective institution will somehow address income and wealth disparity in. the United States," —DICK RAMSDEN P'84, P'86

Selectivity vs. Opportunity

I apreciated the thoughtful essay by Robert Reich '68 on education ["The Opportunity Divide," Mar/Apr] and completely support his recommendations to recruit students from financially and otherwise diverse backgrounds. I was a limited-income, academically underprepared (for Dartmouth), Southern female student shortly after coeducation began. My first year at Dartmouth was very tough. An LSA in Mexico with pro- fessor Sara Castro-Klaren, organic chemistry classes with professor Dick Shafer and friendships throughout those years helped me regain my confidence and enabled me to stay on, graduate cum laude, and five years later graduate with honors from Dartmouth Medical School. It has taken me 15 years to pay off the debts associated with this education, but I am pleased to have done so, and am now in a position to (modestly) help and support others with similar backgrounds and goals. I hope that admissions at Dartmouth continue to be need-blind, adequate scholarships are available, and active, unique efforts are made to keep students there, especially in the early years. On a national level we need something like the GI Bill (but without another world war) to help low and middle income students with both undergraduate and graduate education.

P.S. I enjoyed Mindy Chokalingam's "badly drawn" cartoons [Jan/Feb] and wanted to let her know that her undergrad insights could have been written for us in the mid-'70's and that except for the Labrador, SUV and The New Yorker (yikes!), we aren't all like the alumni she depicted!

Minnetonka, Minnesota

Contraryto Robert Reich's Belief that "increasing competition [in higher education] will exacerbate the widening inequalities" that have "corrosive effects on democracy, social solidarity and the moral authority of a nation," competition is what encouraged so many members of my parents' and grandparents' generations to work exceedingly hard and provide greater educational opportunities for their children.

Unfortunately, Reich fails to recognize that many successful Dartmouth alumni are not the offspring of uppermidle-class Ivy League graduates like him, but of parents who attended public universities and poor immigrant grandparents who never attended college. Rather than placing the burden on top schools to sacrifice high academic standards in an effort to achieve equality of opportunity, it is the duty of those noncompetitive applicants to make the best of their current skills and work diligently to provide greater opportunities for their own offspring.

Ithaca, New Yorkajs59@cornell.edu

AS AN EDUCATION CONSULTANT AND co-author of How to Get Into the Top Colleges (Prentice Hall, 2000), I was naturally interested in Robert Reich's "The Opportunity Divide." The information he offered to support his argument regarding college admissions trends and their effect on the ever-widening inequality gap tells only one part of the story. I disagree with his assessment of the root of the evil.

larly accept candidates from low-opportunity backgrounds with comparatively weak SAT scores and grades (not to mention great financial need) over those whose numbers are impressive but have had greater opportunity for success—I see this time and again. Princeton recently abolished all loans in its financial-aid packages, making it a cinch for those admitted to attend, regardless of financial circumstances (Dartmouth and other colleges have changed their financial-aid packages to similarly benefit low-income students in recent years). Combating the legal abolishment of affirmative action in admissions, "public Ivies" such as UC Berkeley have instituted alternative policies specifically aimed to benefit minorities and I have witnessed college admissions trends and aided hundreds of students in the application process for manyyears; furthermore, I am in contact with admissions and financial-aid officers at a wide range of colleges. While I concur that education plays an increasing role in separating the haves from the have-nots in our society, I disagree with Reich's premise that the selective colleges help to promote the interests of the franchised over the disenfranchised. On the contrary, the most selective colleges do not engage in "bidding wars" for middle to upper-class superstars, but instead reserve their aid for the neediest students. In the interest of diversifying their classes, the top colleges regularly other students of low opportunity.

Fortunately, most of the top colleges are doing all they possibly can to find, admit and grant aid to promising students from the most disadvantaged backgrounds. The root of our problem lies not within the admissions practices at institutions of higher learning, but within the poor quality of our institutions of "lower learning." Making it easier for children from poor families to gain access to post secondary education is a matter of improving our public elementary and high schools, so that these students can show they have the kind of promise that the colleges are desperately trying to unearth. Present a poor, yet promising, student to most colleges and they will gladly spend their resources to help him or her attend.

I commend Dartmouth for doing its best to admit (need-blind) a wide range of promising students from diverse backgrounds and hope this trend at our top colleges will continue.

San Francisco, Californiakklein1@earthlink.net

ROBERT REICH ASSERTS THAT "reputable four-year institutions" are increasingly selective and applicants from lower-income families are being left out. He is half right. Over the last 2,5 years most institutions have greatly expanded their markets, by both going coeducational and reaching out to students who in times past might not have applied, particularly low-income and minority students. One would assume that this is to be applauded; somehow for Mr. Reich it is a source of alarm.

Reich believes that selective institutions are not spending enough on financial aid, nor focusing it sufficiently on lower-income students. Here he is wrong. One call to the Consortium on Financing Higher Education (COFHE) a research group of 31 of the nations leading private colleges and universities that was founded by President Kemeny at Dartmouth in 1974 and now is based at MIT—would have shown this to be a fallacy. The truth is that the fastest growing expenditure over the past decade at selective, private institutions has been financial aid. Helped by growing endowment values, it has grown much faster than student charges.

As a former trustee and chief financial officer at Brown University, let me cite some facts, not hearsay. In the past decade, Browns undergraduate grant aid has grown 9.7 percent per year compounded; tuition and fees have grown at 5.3 percent compounded. This year Brown will spend $33 million on undergraduate grant aid. Only about 27 percent of that comes from endowment income specifically designated for financial aid. The largest source of support for grant aid is tuition. If this is true at Brown, with an endowment of $1.5 billion, it is even more prevalent at less fortunate private institutions. If anyone is being shortchanged, it is not the lower-income financial-aid applicants Mr. Reich is so concerned about, but the middle-class families who go to extraordinary lengths to pay todays tuitions-not only their own, but to support the grant aid of others.

Mr. Reich's essay is based on the faulty premise that going to a selective institution will somehow address income and wealth disparity in the United States. I would suggest to Mr. Reich that success in life does not depend on where you go to school. It is important that you succeed in a course of study somewhere. Having some intelligence and skills is the price of admission to a job; from that point forward it is how effective you are that determines success. Where you went to college is usually forgotten and irrelevant.

If Mr. Reich truly wishes to help the less fortunate, he should focus on their preparation in the K-12 years and espouse real competition in public education, from charter schools to vouchers. He should also get behind reform of Social Security so that low-income families, who have no property rights under the present system, can build family wealth through individual accounts invested in real assets, wealth that can be passed on to a spouse and children.

Director of COFHE, 1974-77Lyme, New Hampshireramlyme@aol.com

Robert Reich has been a frequent and articulate advocate for how the United States can include all of its citizens in the prosperity that has come about because of globalization. Unfortunately, going after selective educational institutions does little to further the goal of assuring that the United States s growing prosperity reaches every corner of the population. How selective a few educational institutions are does not affect the diffusion of the skills necessary to succeed in a global economy.

The selectivity statistic is simple enough. It arises from the math: A school is selective when more students apply than are accepted. A low acceptance rate (or a high rejection rate) equals selectivity. The key to being selective is for a relatively. large number of students, for whatever reason, to apply even as many of them know the odds are low that they will be accepted.

It is easy to see why an administrator might favor increasing the selectivity of her institution. Selectivity statistics are one the few objective measures of the perception of the relative attractiveness of colleges. Why do students and their parents persist in tossing application money in the direction of highly selective colleges? After all, as Reich pointed out, "the assumption of a direct correlation between selectivity and future earnings is not borne out by the research." One of the primary attractions of selectivity is that it winnows through the masses. Smart, capable students find attractive the prospect of going to school with students of similar abilities.

The reality is that not many schools are very selective. According to the 1997 edition of The Best Colleges, published by The Princeton Review, of the 310 colleges profiled, only 16 had an acceptance rate of less than 25 percent.

Selectivity is not why children from poorer backgrounds do not attend college. In every state as well as most larger communities there are public access institutions that accept virtually every qualified applicant. The United States has more than 1,000 junior colleges and 2,000 four-year institutions. If someone is qualified to go to college and wants to go, there is a school that will take him.

Los Altos, Californiateda@eos.com

Green Space Matters, Too

With the northward expansion of the College ["North Campus Takes Shape," Mar/Apr], I only hope College planners keep this in mind: Open spaces such as Tuck Mall are just as important to students as new buildings.

Fort Irwin, Californiakyle.b.teamey.98@alum.dartmouth.org

Brains and Brawn

"The Sporting Lief" [May/June] pumped me. I hope that is sufficient sports lingo to say that these articulate young female athletes are as awesome to me as any athlete I ever climbed onto the gridiron with (I was All-Ivy, All-New England, All-East and Honorable Mention All-American many moons ago). They totally refute the myth that one can't be simultaneously athletic and introspective, especially the young women who grappled successfully with the double-edged specter of competition in their statements. It makes me tear up to know that my daughter, an 'O4, is at the erg machines, in the tanks and on the river in the wee hours of the morning with such thoughtful and powerful young women.

Houston, Texasadamsarc@net1.net

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

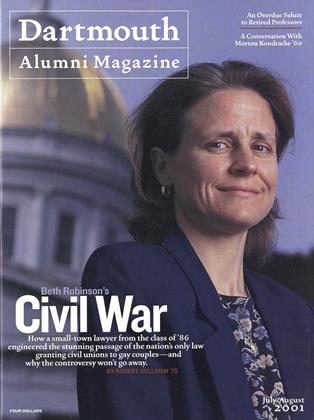

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Civil Action

July | August 2001 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of Emeritus

July | August 2001 By Jay Parini -

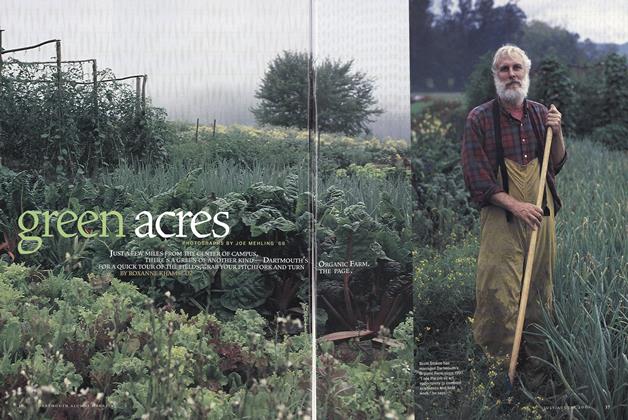

Feature

FeatureGreen Acres

July | August 2001 By ROXANNE KHAMST ’02 -

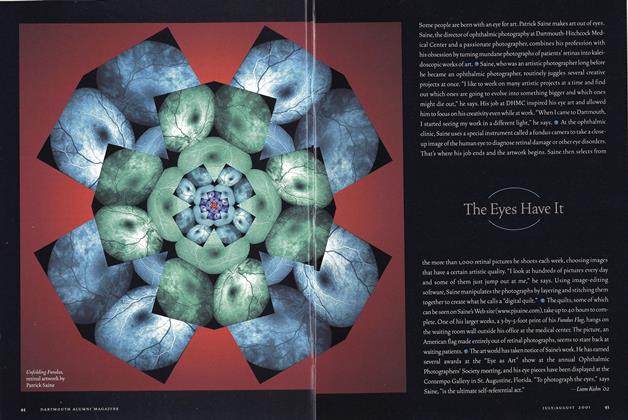

Feature

FeatureThe Eyes Have It

July | August 2001 By Liam Kuhn ’02 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July | August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYA Breed Apart

July | August 2001 By Marcus Coe ’00

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

JANUARY, 1928 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

November 1946 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

NOVEMBER 1963 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JANUARY 1969 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

December 1976 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

NOVEMBER 1984