Heaven and Hell in the Middle East

Anthropology students get a unique glimpse of a rarely seen Al Qaeda recruitment video.

July/Aug 2002 Alex HansonAnthropology students get a unique glimpse of a rarely seen Al Qaeda recruitment video.

July/Aug 2002 Alex HansonAnthropology students get a unique glimpse of a rarely seen Al Qaeda recruitment video.

IN A DIMLY LIT CLASS

room a television screen flickers to life and, in a few minutes, is showing images the general public probably won't ever see.

On the screen is Osama bin Laden, alleged mastermind of the September 11 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington. Standing at a microphone as if he's addressing a crowd, bin Laden reads a prayer and praises the suicide bombers of the USS Cole, the destroyer attacked in October 2000 while it was moored in Aden, Yemen.

Then a fast-moving montage of images originally broadcast on CNN and other networks show acts of violence committed against Muslims, followed by scenes of American leaders such as Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton meeting with Arab leaders such as Kind Fahd of Saudi Arabia. "How could it be permitted that Americans are allowed to wander freely in the 'land of the two holy places?'" says bin Laden, implying that leaders in the Middle East are more interested in helping America than they are their own people.

The video—90 minutes of searing, often violent images and vengeful, overtly religious narration—is one of the tools bin Laden used to recruit young, devout Muslim men who resent repressive, secular governments in the Middle East and Central Asia—young men whose resentment could then be channeled into rage against the United States.

Dale Eickelman '64, a professor of anthropology who specializes in the Middle East, obtained a copy of the video late last year. He showed it in his winter-term course "Thought and Change in the Middle East and Central Asia."

Eickelman won't say how he got the tape or from whom. "The source is aware of the purposes to which I am putting it," and agrees with those purposes, he says. "I think that it is important to have a clear idea of the nature of the enemy, and to try to understand how this enemy, Al Qaeda, tries to appeal to its primary audience."

But Eickelman isn't showing the video to anyone outside his class. His students have the context necessary to understand it, he says. They didn't watch the video until well after the mid-term exam, when they were immersed in the issues facing the Middle East.

Eickelman's course explores an increasingly fragmented Muslim world. With rising levels of education, greater ease of travel and proliferation of media, Muslims are exposed to a range of views far wider than what was available 20 or 30 years ago, Eickelman says. The torrent of new ideas and interpretations is breaking down established authority in Muslim countries, and bin Ladens terrorist network is a prime example of the sort of fringe groups that are finding room to operate. That means winning hearts and minds, exactly the aim of the recruitment video.

"It was definitely very well thought out," says Jaclyn Taub '05 after watching the video. "I can see how people definitely believe him."

In the video, bin Laden appeals to the viewers devotion to Islam, sense of shame at the condition of the Muslim world and appetite for retribution. Throughout the video, religious songs and poems and recitations from the Koran, Islam's ancient holy book, strike chords of lamentation and, later, of revolt.

One sections shows images of starving Iraqi children. Immediately after comes footage of then-President George H.W. Bush walking with American troops in the desert, then a similar image of Saddam Hussein with his troops. The placement of the images suggests that Bush and Hussein are of the same cloth, tyrants who have done nothing to ease the suffering of Iraq's children. It's a technique used throughout the video.

"In what religions name do they besiege those children...? Why do the Iraqi children have to be punished?" says bin Laden, shown sitting in the shade.

This is part of the videos first section, titled "The Situation," which depicts violence against Muslims in Chechnya, Lebanon, Kashmir, Indonesia and elsewhere. In subsequent sections, titled "The Cause" and "The Solution," bin Laden explains that Muslims are too preoccupied with worldliness and must devote themselves to strict Islamic law and armed struggle against Israel and America.

Stirring religious music plays over images of Al Qaeda soldiers training in Afghanistan, conducting mock raids on homes in which targets shaped like human torsos have crosses painted on them. A song calling on Muslims to rise up and fight plays over nighttime footage of glowing artillery streaking into the night sky.

"This is a boy's film," Eickelman tells his class. It was made to appeal only to boys and young men by showing them a sort of desert Never-Never Land.

The Peter Pan, of course, is bin Laden, who at the beginning of the tape speaks like a religious scholar, decrying the spiritual weakness of Muslims. By the tapes end, he has been transformed into a calm, calculating military leader, dressed in fatigues, with a rifle visible behind him. "Only blood is going to wipe out the shame and dishonor among Muslims," he says, late in the video.

In discussions after the video, students remark on the effective use of footage from news sources such as CNN, the BBC and the Qatar-based Arab network Al Jazeera. But having seen other views of life in the Muslim world, they are quick to poke holes in bin Laden's apocalyptic views.

What the video offers Muslim youth is not a better way of life, but an honorable way to die. "It isn't really a solution," says Allison Schumitsch '02. "You never get a clear idea of where this movement is going."

Aly Rahim 02 comments that experts on terrorism and the Middle East have said universally that bin Laden and other Islamic extremists are motivated by their hatred of the decadent West. "This video underscores what actually attracts a terrorist," he says. "It's really disaffection with their local regimes."

"The source of the hatred isn't miniskirts," he adds.

Eickelman's students see the Muslim world in a richer context than the casual television viewer does. They know that "Islam is as much a Western religion as Christianity and Judaism, and that the children of Abraham have much more in common than Americans normally acknowledge," Eickelman says after class. They also know that more thoughtful Muslims are advocating nonviolent change'. "Islam—and Muslims—are not the enemy," he says. "Bin Laden is the poster boy, so to speak, for a certain sort of terrorism. He has more in common with the Baader-Meinhof gang, the Red Army faction and Irgun than with many other Muslim groups."

If enough context were provided, the video could be shown to a wider audience, students say. "It would be a difficult thing to show," Schumitsch says, but with subtitles and scholarly commentary, "I don't see any reason why you couldn't do that."

One reason the video might remain invisible is that the media have been heeding appeals from the government not to air or print complete statements from bin Laden, out of fear that they might contain messages to Al Qaeda cells and that the news media would be giving him a platform for his views.

But would an American audience get something out of it? "Some of the stuff that is ugly for Americans to hear is news," Eickelman says. "I think one of the steps in knowing about the world is really listening to what people are saying."

The sights and sounds in the bin Laden video are unpleasant indeed, not least some of the final images. These show children engaging in the same military training as adult Al Qaeda fighters. Eickelman, who translated some of the narration, says those scenes convey an ominous message: Islamic militants are beginning a long, violent struggle against the United States.

The Face of Terror Grasping binLaden's appeal may help Americansthwart future attacks, according toprofessor Eickelman.

COURSE: Anthropology 27: "Thought and Change in the Middle East and Central Asia" PROFESSOR: Dale Eickelman '64 PLACE: 317 Silsby, four hours per week GRADE BASED ON: Mid-term, oral presentations, role-playing exercises, discussions and short papers Readings: The MiddleEast and Central Asia:An Anthropological Approach by Dale Eickelman (Prentice-Hall), Being Modern in Iran by Fariba Adelkhah (Columbia University Press) and Taliban: The Storyof the Afghan Warlords by Ahmed Rashid (Yale University Press)

Alex Han son is a staff writer at the Valley News in West Lebanon, New Hampshire.This article is reprinted with permission of the Valley News.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Matter of Principle

July | August 2002 By Rick Green -

Feature

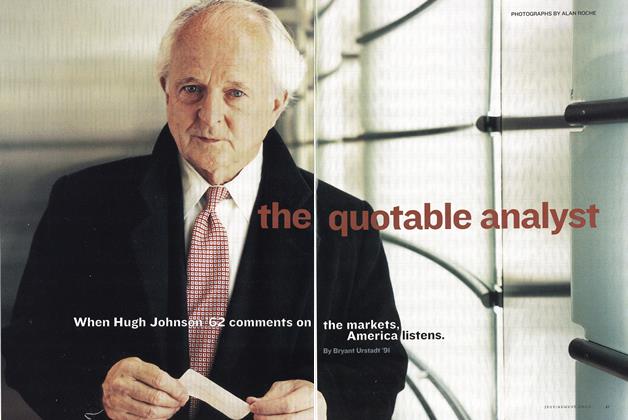

FeatureThe Quotable Analyst

July | August 2002 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

FeatureFENG SHUI COMES TO DARTMOUTH

July | August 2002 By ROBERT NUTT '49 -

Outside

OutsideRunning With Wild Abandon

July | August 2002 By Jay Heinrichs -

Interview

Interview“We’ve Got To Go For It”

July | August 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

July | August 2002

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMA Body in Motion

MAY | JUNE 2018 By GEORGE M. SPENCER -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNot Lost in Translation

Sept/Oct 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

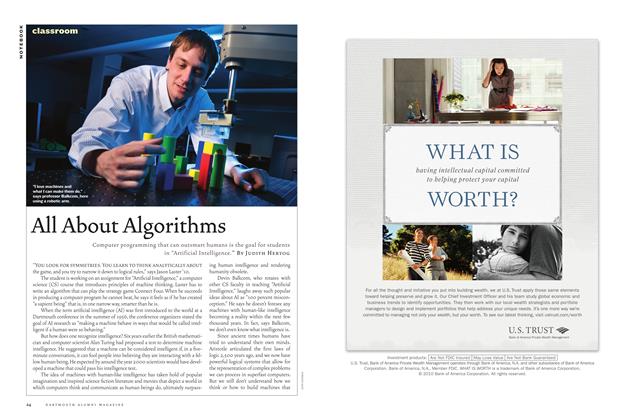

CLASSROOMAll About Algorithms

Sept/Oct 2010 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMThe Risk of Regulation

July/August 2012 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhen Rights Encourage Wrongs

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By JUDITH HERTOG -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhy the Play’s Still the Thing

May/June 2001 By Karen Endicott