Optimus Maximus

Skeptics told professor Paul Christesen ’88 his “Antiquity Today” class wouldn't draw students. Then it became the largest classics course in 25 years.

May/June 2008 Judith HertogSkeptics told professor Paul Christesen ’88 his “Antiquity Today” class wouldn't draw students. Then it became the largest classics course in 25 years.

May/June 2008 Judith HertogSkeptics told professor Paul Christesen '88 his "Antiquity Today" class wouldn't draw students. Then it became the largest classics course in 25 years.

THE ANCIENT PAST TENDS TO BE SO ALIVE IN OUR MODERN IMAGINATIONS that we often forget that what we know is limited. Movies, books and paintings have created such a vivid image of the past that it seems possible to step right into a gladiator fight at the Coliseum or to join Socrates and Phaedrus for a drunken debate on the nature of love. But, as classics professor Paul Christesen argues, much of what we think we know about ancient Rome and Greece is actually projections of our own concerns and values onto antiquity. A movie such as Spartacus, for example, says more about America in the 1950s than about Rome. This is what makes the study of an- tiquity so interesting, says Christesen, who teaches "Antiquity Today," one of his department's most popular courses: "It can tell us a lot about who we are and what we think about the world today."

In Antiquity Today" Christesen challenges students to abandon their idealized images of antiquity and look at what is really known about ancient Rome and Greece. The classical texts that we know today probably make up less than i percent of all ancient literature, he points out to his students. "Papyrus couldn't last more than 30 years, so texts that weren't recopied regularly would be lost within a generation." Through cultural comparison between ancient civilizations and todays society, Christesen wants students to scrutinize values and assumptions they take for granted.

Christesen came to the study of antiquity via a 10-year detour running his family's bicycle business. But his passion for history persisted and he pursued a Ph.D. at Columbia University, where he wrote a dissertation that explored how value systems affected the structure of the economy. Contrary to traditional economic theorists, Christesen is convinced that human behavior is shaped more by cultural values than by monetary self-interest. "The old assumption was that people are driven by gain, but that is simply not true," says Christesen, pointing to himself as an example.

In 2001 Christesen joined the classics department. When he proposed to offer 'Antiquity Today" as an introductory course, some members of the department expressed concern that the course would not attract enough students, but more than 275 students enrolled, making it the largest classics course taught on campus in 25 years. The course, now capped at 150, usually has a waitlist.

"In the past classics was taught as a given," says Christesen. "Nobody questioned the rationale for studying antiquity. Rome and Greece were idealized, and any educated individual had to study classics." In the 1960s and 19705, as colleges started to make more room for the study of non-Western cultures, classics went from being the center of academic life to being just another department. "The field went through a period of disorientation," says Christesen."There was this sense of loss among classicists." Christesen isn't among those nostalgic for the days when ancient Greece and Rome were consid- ered the pinnacles of civilization. He says Roman and Greek culture are still important because they influenced Western cultures, but not because they were greater than other cultures.

"Some students come in thinking it was all wonderful," he says. "That's why I start the course by talking about violence to disabuse them of the notion that these were all wonderful people who walked around talking philosophy all day."

Christesen organizes the course to oscillate between the foreign and the familiar. Whenever students start feeling too much at ease he presents them with an aspect of ancient Rome and Greece that is radically foreign to todays values. To illustrate Roman society's shockingly casual attitude toward violence, for example, Christesen cites graffiti found on a Pompeian wall advertising the comfortable awnings that provide shade to the audience as they watch gladiator fights, the slaughtering of exotic beasts and crucifixions. The bloodier, the better: Trained lions were used to kill and eat defenseless prisoners and thousands of human beings and animals were typically slaughtered during major imperial gladiator games. Through an exploration of attitudes toward violence, honor, political structure and sexual identity in ancient Greece and Rome, Christesen invites students to rethink their own values. "This is a liberal arts institution, which means that we want people to liberate themselves and consciously rethink who they are," he says. "Everyone is shaped by their culture and their history. The person sitting next to you might have a completely different worldview from you, and hearing what they have to say may be incredibly important to your understanding of the world."

To encourage discussion Christesen often opens a class by randomly calling on a student for a personal opinion on the day's topic.

"Professor Christesen is my model for teaching at its best," says David J. Knight '10, who is interested in a teaching career and who is considering a double-major in religion and classics. Knight recounts in awe that when he once e-mailed Christesen at 3 a.m., he received an immediate reply.

Christesen has received several awards recognizing his dedication. He was the Class of 1962 Faculty Fellow of 2004-05 and received the 2007 Huntington Memorial Award for newly tenured fa- culty. In 2006 the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching named him New Hampshire Professor of the Year. "I really believe in the transformative power of education," says Christesen.

One example of that power is Brett Lowe 'OB, a government major. He first took "Ancient Greek Athletics" with Christesen because, as a football player, he was intrigued by the topic. Lowe says he expected to feel affinity to ancient Greek culture because of its appreciation of both body and intellect, but he was startled to learn that the Greeks exercised in the nude, well oiled, and that for them athletics were a celebration of male beauty and homosexual eroticism. "We're shaped by our background and what our society says is the norm," he says, having shrugged off his initial surprise.

Lowe recalls being particularly struck by a passage from The Iliad. In it Achilles, disillusioned with war, decides to sail home. His friends try to persuade him to rejoin the battle and promise him fame and immortal glory (kleos) if he proves himself a valiant warrior. Achilles replies that in the face of death, glory doesn't mean a thing, and that he'd rather be peacefully at home with his family.

Lowe says that he too feels peer pressure to pursue fame and glory, even if he's not sure that's what he really wants. He has just accepted a job in finance and worries it won't make him happy. "Is it worth sacrificing your youth, your time and the things you enjoy for money and status?" he asks. Even Achilles eventually decided to rejoin the battle, died a hero's death and went down in history as the greatest of all Greek warriors, whose glory still speaks to our imagination today.

Don't Know Much About Classics? "The best way to get to know the Greeks and Romans is to read what they had to say about themselves," says Christesen. He suggests: Robert Fagles' translations of Homer's The lliad (Viking, 1990) and The Odyssey (Viking, 1996) and Virgil's The Aeneid (Viking, 2006) Greek Lyric Poetry, from authors such as Sappho and Archilochus, assembled and translated by Martin West (Clarendon Press, 1993) Catullus: The Complete Poems, translated by Guy Lee (Oxford World's Classics. 1990) Any of the plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides or Aristophanes, starting with Sophocles' Antigone or Aristophanes' Frogs Plaptus Pot of Gold, translated by E.F. Watling (Penguin Books. 1965) Herodotus' The History, translated by David Grene (University of Chicago Press, 1987) Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War Livy's History of Rome

Judith Hertog is a regular contributor to DAM. She lives in Norwich, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

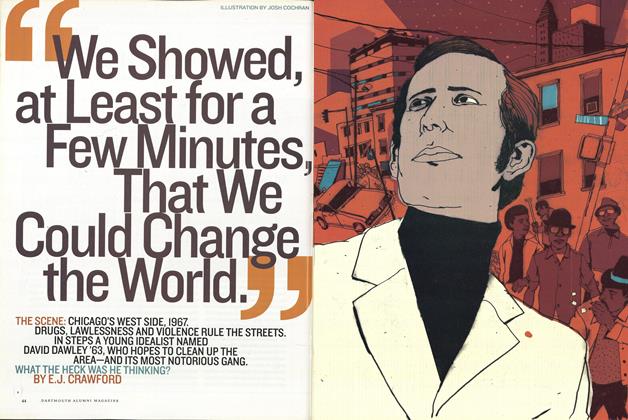

Cover Story“We Could Change the World”

May | June 2008 By E.J. CRAWFORD -

Feature

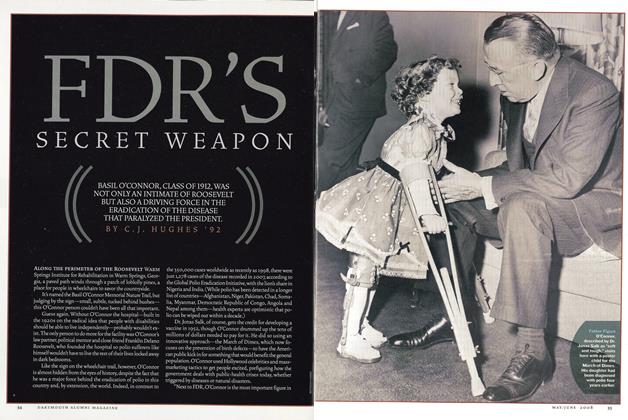

FeatureFDR’s Secret Weapon

May | June 2008 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

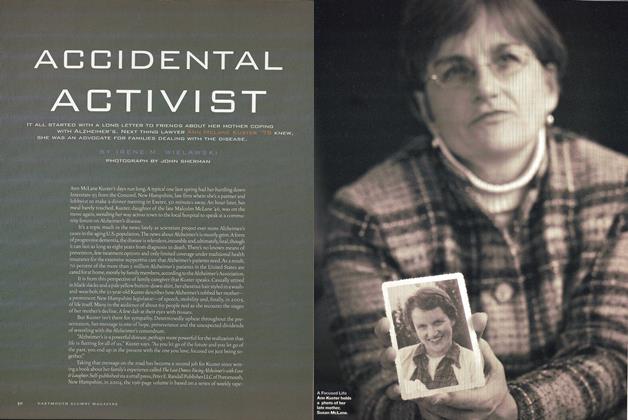

FeatureAccidental Activist

May | June 2008 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2008 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2008 By Kit Wilson '89 -

Tribute

TributeThe “Prone Ranger”

May | June 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08

Judith Hertog

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNot Lost in Translation

Sept/Oct 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNuts and Bolts

Mar/Apr 2010 By Judith Hertog -

Article

ArticleDarkroom Magic

Nov/Dec 2010 By Judith Hertog -

Article

ArticleSimian Sensibility

Nov - Dec By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMReality Show

NovembeR | decembeR By JUDITH HERTOG -

TECHNOLOGY

TECHNOLOGYA Monitored State

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By JUDITH HERTOG

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMA Body in Motion

MAY | JUNE 2018 By GEORGE M. SPENCER -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNot Lost in Translation

Sept/Oct 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNuts and Bolts

Mar/Apr 2010 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhen Rights Encourage Wrongs

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By JUDITH HERTOG -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Human Condition

Sept/Oct 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMFrom the Page to the Stage

Mar/Apr 2002 By Karen Endicott