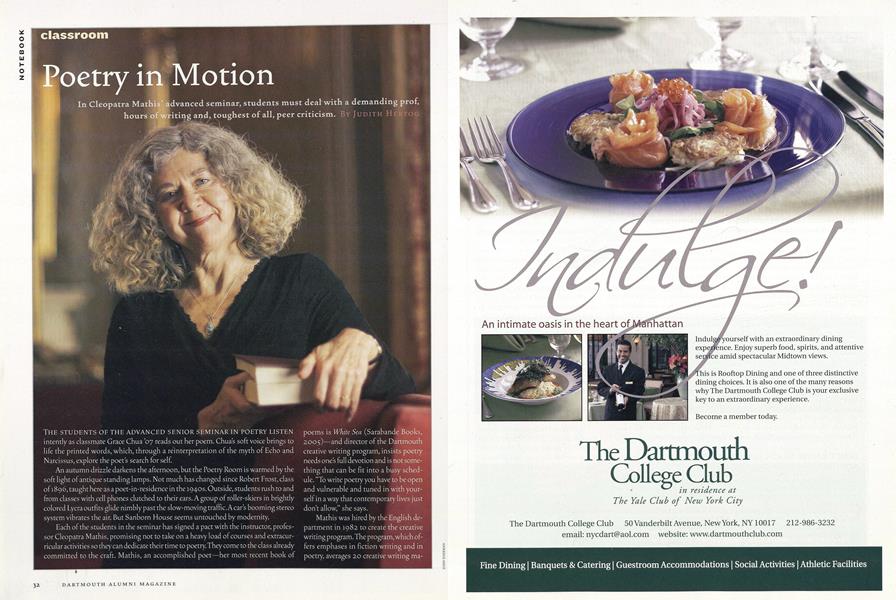

Poetry in Motion

In Cleopatra Mathis’ advanced seminar, students must deal with a demanding prof, hours of writing and, toughest of all, peer criticism.

May/June 2007 Judith HertogIn Cleopatra Mathis’ advanced seminar, students must deal with a demanding prof, hours of writing and, toughest of all, peer criticism.

May/June 2007 Judith HertogTHE STUDENTS OF THE ADVANCED SENIOR SEMINAR IN POETRY LISTEN intently as classmate Grace Chua '07 reads out her poem. Chua's soft voice brings to life the printed words, which, through a of the myth of Echo and Narcissus, explore die poets search for self.

Each of the students in the seminar has signed a pact with the instructor, professor Cleopatra Mathis promising not to take on a heavy load of courses and extracurricular activities so they can dedicate their time to poetry. They come to the class already committed to the craft. Mathis, an accomplished poet—her most recent book of poems is White Sea (Sarabande Books, 2005) and director of the Dartmouth creative writing program, insists poetry needs ones full devotion and is not something that can be fit into a busy schedule. "To write poetry you have to be open and vulnerable and tuned in with yourself in a way that contemporary lives just don't allow," she says.

Mathis was hired by the English department in 1982 to create the creative writing program. The program, which offers emphases in fiction writing and in poetry, averages 20 creative writing majors each year, making up about one third of all English majors. The senior seminar is the most advanced course in the program, and all participants are creative writing majors or minors.

Students are required to write two poems each week and carefully revise half of those so that by the end of the term they have at least nine poems close to completion. Mathis describes herself as a demanding teacher and harsh critic, but says she is also very protective. She strives for an environment where students feel safe to take the emotional risks needed to write well. "I try to support my students emotionally as much as I can," she says. "With undergraduates that is particularly important because they are trying so hard to discover not just themselves as writers but to discover who they are as people."

As the hours progress and the sky turns from pale gray to night blue, the students read from their poems about suicide, passion, alienation, love, regret, redemption and death. Rena Mosteirin '05, an English major who will graduate this year and plans on becoming a professional poet and poetry teacher, hands out "Hungerstrike," a poem she rewrote the previous night. (It will later appear in an issue of The Stonefence Review, Dartmouth's quarterly literary magazine.) "I'm asking you to help me do some slashing to get this down to four lines," she says cheerfully. Everyone laughs, looking at the two full pages just distributed.

After Mosteirin has read her poem to the class, she sits back to listen to the discussion. To encourage authors to open themselves up to criticism, Mathis does not allow them to defend or explain their works while they are being discussed by classmates.

The group dissects the poem and puzzles over the connection between seemingly unrelated narratives: a hunger strike, the death of a boyfriend, a relationship, a scheduled MRI scan and a conversation between the narrator and a homeless man named Waterhead:

And then I said Waterhead, what do youwant?What do you really want, more than anything?And he puffed a little on his joint to get itstartedand smiled and said Strawberrymilkand we sat there in the pink glow of theword.

Mosteirin plays with a strand of hair, not showing any emotion as her classmates try to figure out if the hunger strike indicates this is a political protest poem and whether the young man who died is a soldier. The group is gentle in its critique—cushioning each criticism with praise—but to remain calm while your innermost thoughts and feelings are up for discussion is a difficult feat.

"The moment before I read a poem to the class I think to myself that everyone is going to hate it," says Mosteirin. "But I like that fear of not knowing what peo- ple will think of your poem. If you don't make mistakes you're not growing. You can just play it safe and follow the style of a poet you like, but this is a time for us to take risks, to experiment, to find our voice and ourselves."

Mathis agrees that at this point in their lives young writers tend to write in order to explore their own psyche and to work out personal questions, but she thinks serious writers need to move beyond the personal: "Whatever drives people to start writing in the beginning is not what will keep them writing," Mathis says. "What will keep them writing is a real love of the art and the craft. Not just that inspired moment in the moonlight when you write down something because you're in love and you want to express that."

This doesn't mean Mathis dismisses the initial rush of inspiration that motivates beginning writers. "It's the teacher's job to move students beyond that," she says, "to create interest in poetry, to make them excited about what the art is capable of doing and to make them want to be an artist, someone who cares deeply about the work of crafting a poem."

Mathis emphasizes that art is communication and that to reach others, the concerns of the self need to be subsumed for the sake of art. "Art is a gift to the world, not a gift to yourself," she says.

Although a good number of graduates from the creative writing program go on to complete M.F.A. programs and become professional writers, many others choose non-literary careers such as law and medicine—which does not mean they have abandoned their interest in poetry. Mathis often receives letters from former students letting her know how important writing and reading still are to them. "That's the big reward," she says, "not how many people went on to graduate school or became published poets."

In this time of computers and instant communication, Mathis believes it is important for people to read. Modern life is too hurried, she says, and allows no time for the things that really matter. "My feeling is that none of us is spending the time we need to pursue activities that give us back something of ourselves, and I think that's what good art does," she says. "It gives a moment of quiet, solace and reflection." a

DON'T KNOW MUCH ABOUT POETRY? CLEOPATRA MATH IS RECOMMENDS THESE BOOKS: Contemporary American Poetry, edited by Poulin and Waters (Houghton Mifflin, 2000). "This is a user-friendly anthology, with a good concentration on the poets who are re- sponsible for the great energizing of American poetry in the 1950s and 1960s, which con- tinues to this day." A Poetry Handbook, by Mary Oliver (Harcourt Brace, 1994). "A lovely introduction to the writing life." The Autumn House Anthology of Contemporary Poetry, edited by Sue Ellen Thompson (Autumn House Press, 2005). "This anthology focuses on recent contemporary poetry." The Eye of the Poet: Six Views of the Art and Craft of Poetry, edited by David Citino (Oxford University Press, 2002). "Six varied poets discuss the writing of poetry and what values it holds for the reader."

JUDITH HERTOG is a freelance writerand frequent contributor to DAM who lives inNorwich, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

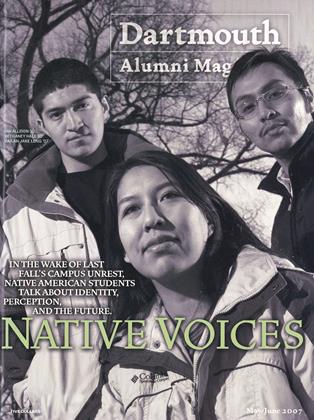

Cover StoryNative Voices

May | June 2007 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’05 -

Feature

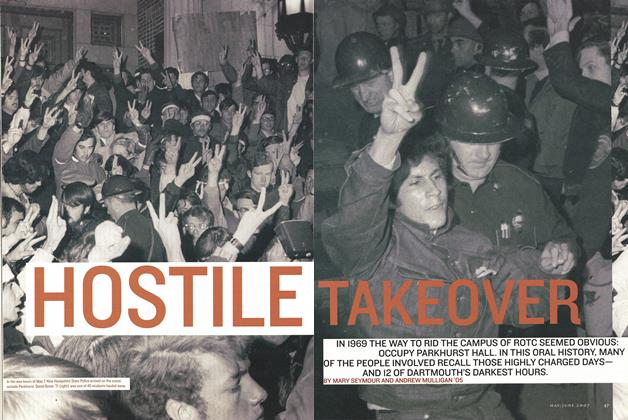

FeatureHostile Takeover

May | June 2007 By MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05 -

Feature

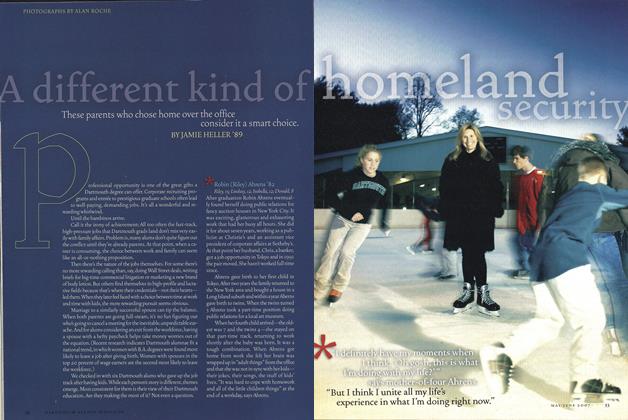

FeatureA Different Kind of Homeland Security

May | June 2007 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2007 By Joe Novak '52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Pursuit of Happiness

May | June 2007 By Daniel Becker ’84

Judith Hertog

-

Article

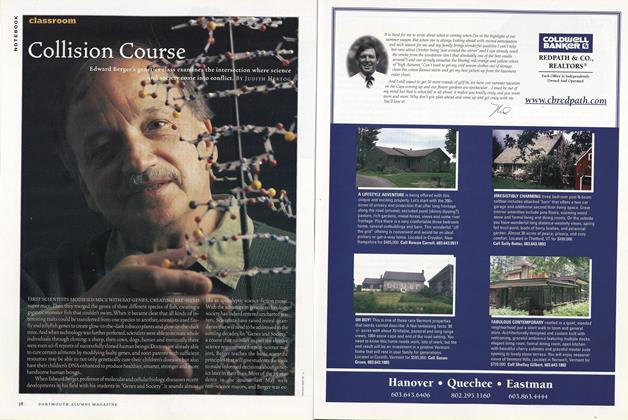

ArticleCollision Course

Sept/Oct 2007 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

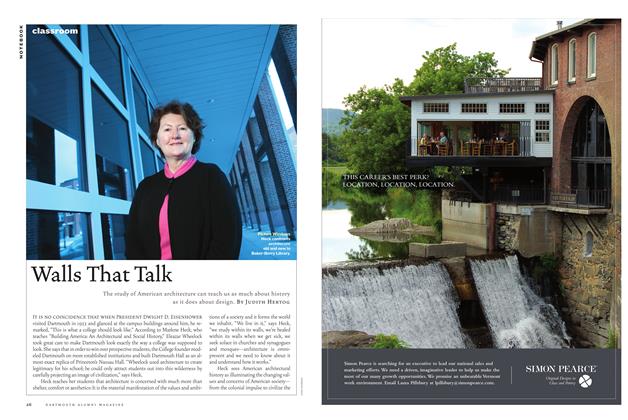

CLASSROOMWalls That Talk

May/June 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMAll About Algorithms

Sept/Oct 2010 By Judith Hertog -

Article

ArticleDarkroom Magic

Nov/Dec 2010 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMStar Struck

Mar/Apr 2012 By Judith Hertog -

Classroom

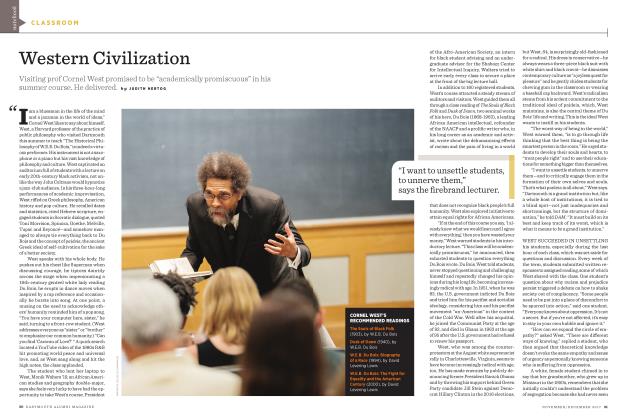

ClassroomWestern Civilization

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By JUDITH HERTOG

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

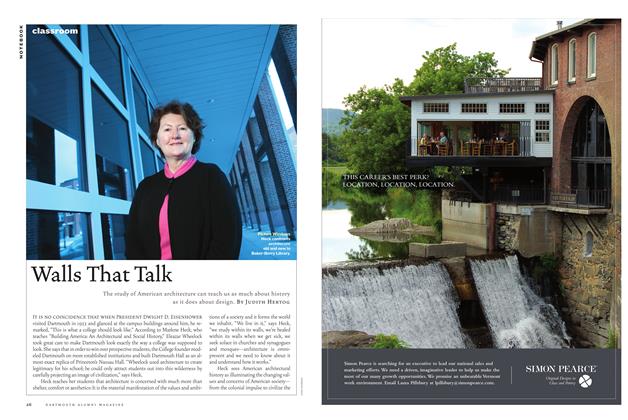

CLASSROOMWalls That Talk

May/June 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMOutside The Box

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By JUDITH HERTOG -

Classroom

ClassroomLearning By Doing

May/June 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhy the Play’s Still the Thing

May/June 2001 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMDigital Dilemma

Jan/Feb 2012 By Kristen Hinman ’98 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWall Papers

July | August 2014 By LISA FURLONG