Running With Wild Abandon

A nice stroll through the woods? Why bother when you can run them thar trails!

July/Aug 2002 Jay HeinrichsA nice stroll through the woods? Why bother when you can run them thar trails!

July/Aug 2002 Jay HeinrichsA nice stroll through the woods? Why bother when you can run them thar trails!

Trailrunning isn't even really a sport, but its the best one I know. It's tourism without crowds, hiking without a pack, the most unextreme of extreme sports. Jogging up the Appalachian Trail behind my friend Jay Davis '90, I show off by shouting a bit of verse from Richard "Men of Dartmouth" Hovey, class of 1885: 'Again among the hills! The shaggy hills! The clear arousing air sounds like the call "of bugle notes across the pines, and thrills my heart as if a hero had just spoken."

Jay just smiles indulgently. In another sport, I would have had something thrown at me. But Jay knows my pathetic level of fitness: By the time we reach Velvet Rocks, all he hears from me is gasping.

Jay and I had agreed to meet at the Hanover Co-op, a convenient but risky departure point. The New York Times has declared it the best supermarket in America; more than one weakly constituted runner has given in to the temptation of free coffee, cheese and pastry samples, and suffered afterward. I browsed the magazine section while Jay changed out of his work clothes in the restroom. A teacher and administrator of a teacher-certification program at Dartmouth, he's one of those hyper-fit grads who stay in Hanover and use the area as a glorious gym.

We cut through the parking lot and onto Chase Field, where the Appalachian Trail takes a momentary jog through campus. Our four-mile-an-hour pace wasn't going to set any records, but it was double the speed of a day hiker, allowing us to squeeze in a good eight miles of rugged terrain in just two hours. Jays mission was to give me a nostalgic tour of the hills surrounding Hanover, exploring Velvet Rocks, Balch Hill, Oak Hill, Storrs Pond, Pine Park and the golf course, returning to campus in time for me to nap before dinner.

Any sport conducted at four miles an hour will never make it to prime time, though some of trailrunning's more elite participants accomplish noteworthy feats in pursuit of pain. An annual marathon scales 14,111-foot Pikes Peak in Colorado. A few athletes have set up permanent residence in isolated Silverton, Colorado, in order to train year-round for the Hard Rock 100—a sufferfest that totals 33,000 feet in vertical gain. The starting line of the Everest Marathon is at 17,000 feet. (We won't talk about those crazy adventure races—the Eco-Challenge, the Marathon des Sables race across the Sahara—which aren't trailruns so much as made-for-TV obstacle courses.) Increasingly, though, trailrunning has spread to the masses, supporting a $300 million business in specialized shoes. According to the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association, more than 1.3 million runners trained on trails at least once a week in 2001.

But long before "extreme sports" became a figure of speech, Dartmouth students and alumni were speed-hiking the trails north and south of campus. In the 1920s the first records were set on the 50mile trail between Hanover and Moosilauke. And in the 1960s the ski team began holding a late-October time trial up Moosilauke's Gorge Brook Trail. Students who couldn't make the run (3.4 miles, 2,500-foot elevation gain) in 60 minutes were kicked off the cross-country team; nowadays coach Ruff Patterson uses the run to fine-tune his students' training. It has become a sort of painful fete for local alumni as well; about a dozen show up each year. Perhaps because the course itself is arduous enough, the competition is relatively laid-back. While the elite students and alumni can reach the summit in 38 minutes (the record is 35 and change), no one abuses me for my 49.

Increasingly, though, trailrunning at Dartmouth is not so much about times and sufferfests as about long, lovely runs through the woods. Coach Patterson leads his team on the regions prettiest runs every Sunday in the fall. The students rise virtuously early, encountering in the bathroom classmates who are just coming in from Saturday night partying. You can see the nordies loping through the woods between Hanover and Moosilauke before hunting season. It's a social scene; everybody runs slowly enough for conversation, employing the trailrunner's trick of asking meaningful life questions on the uphills.

Trailrunning does have its hazards, of course. I've run into a tree when not looking (twice) and once pulled a tree down onto myself while taking a hairpin turn. Running along Cummings Pond in Lyme with John Donovan, former director of Dartmouth's Outdoor Programs, we got lost in a deerfly-infested swamp with no shirts and no water, smacking the insects off each others bare, sweaty backs before finding our car after 13 miserable miles. Once I plotted an epic run with Tyler Stableford '96, president of the Mountaineering Club. We would run the entire Franconia Ridge in the White Mountains, all 27 miles, covering four peaks ranging in height from 4,000 to 5,200 feet. But too many other Dartmouth students wanted to join in. (It's a fault endemic to the campus: Any untried experience is considered a good one.) Not wanting to be responsible for the lives of thinly clad students on terrain notorious for its horrible weather, Tyler and I abandoned the plan. Instead, I decided to run solo, 28 miles from Route 25A in Wentworth to my home in Hanover. My wife dropped me off, and I made it to my yard in seven hours and one second, running over Cube, Smarts, Holts Ledge (the Skiway) and Moose. I did it in basketball shoes that proved to be too small and lost several toenails, one of which my son took to school for display in a science exhibit.

I've never run out of surprises. Twice over a three-year period I was attacked by a territorial goshawk. Once, while running down a logging road on Moose Mountain, I almost trampled a couple in flagrante delicto. They were doing it right in the middle of the trail. Without thinking, I leaped over them, murmuring "Excuse me" while the woman looked up with saucer eyes. The couple is doubtless still in therapy.

Nothing nearly that exciting happened on my run with Jay Davis. He kept a gentle pace up the leaf-strewn trail, chattering as if he were still in the office. "It's really the best kind of training," he said. "The climbs give you interval training, while the unevenness of the trail slows you down on the flats and downhills. Most of the time your heart is at 70 percent aerobic capacity." Endurance athletes spend serious money on heart monitors to keep their bodies performing at this level—a rate that trains them to burn fat and keep from bonking over long distances. By the time we got to Velvet Rocks, though, my own heart rate was redlining. I was close to bonking, and Jay was kind enough to pause. We stood in the greeny gloom and listened to the silence. Just 20 minutes from campus, I could hear nothing but my own fast-beating heart. I caught my breath just enough to point out the stand of pines where John Ledyard, class of 1776, bedded down in Dartmouth's first-ever recreational camping trip.

"Well!" Jay said, and he began jogging downhill.

We zigzagged down the trail to Wheelock Street, past the cabin of a man who carves wooden bowls for a living, and up the trail to Balch Hill. Looking west we could see the snowy slopes of Killington. There's a bench at the top of Balch where you can sit and lord over the campus. I looked at it longingly.

"Okay?" Jay said, and he began running again.

We swooped down through the woods, bushwhacking a bit as Jay sought a direct path to the dirt Grasse Road along the Second Hanover Reservoir. We took the trail up to Oak Hill, leaving suburbia behind, following the cross-country ski trails laid out by former ski coach John Morton. Those trails give Dartmouth home-court advantage, in the same way the warped floor boards in the Boston Garden used to assist the Celtics. Oak Hill was originally a downhill ski area, and its precipitous slopes have caught opposing cross-country teams unawares for years. We ran down the switchbacks to Storrs Pond and circled it up to the elementary school, where we paused to look up at our hilly circumnavigation. Then on to the newly expanded and reshaped Country Club. Jay led me up and over the links and down through Pine Park, mercifully skirting notorious Freshman Hill, until Baker Tower came into view and I ran out of juice. Our run became a painful slow jog as Jay led me to the Hopkins Center and we parted ways. I glanced at my watch: two hours, exactly. I limped into the Inn.

So it isn't a sport. It's a, what, a pastime, a lovely diversion, a woodland tete-a-tete, a pleasingly excruciating form of striving in which one attempts to look perfectly relaxed—the sort of demeanor that, come to think of it, defines the Dartmouth ethos. If only all our revisits could be done this way; if only we could have our courses, our pro- fessors, our whole time on campus restored to us, at fast speed, in two afternoon hours. I stumbled past the rocking chairs of the Inn porch and felt a part of my past restored, renewed, condensed.

Jay Heinrichs is aformer editor of Dartmouth Alumni Magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Matter of Principle

July | August 2002 By Rick Green -

Feature

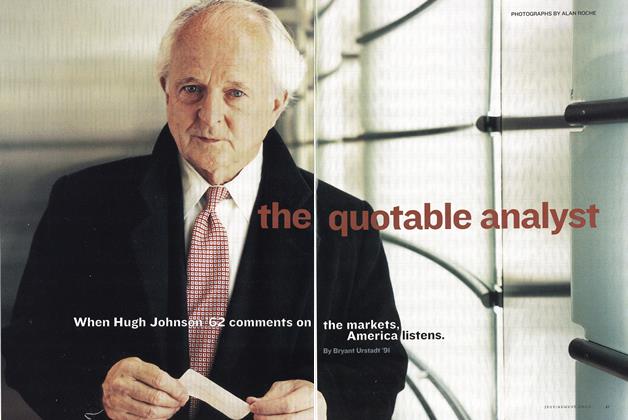

FeatureThe Quotable Analyst

July | August 2002 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

FeatureFENG SHUI COMES TO DARTMOUTH

July | August 2002 By ROBERT NUTT '49 -

Interview

Interview“We’ve Got To Go For It”

July | August 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMHeaven and Hell in the Middle East

July | August 2002 By Alex Hanson -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

July | August 2002

Jay Heinrichs

-

Cover Story

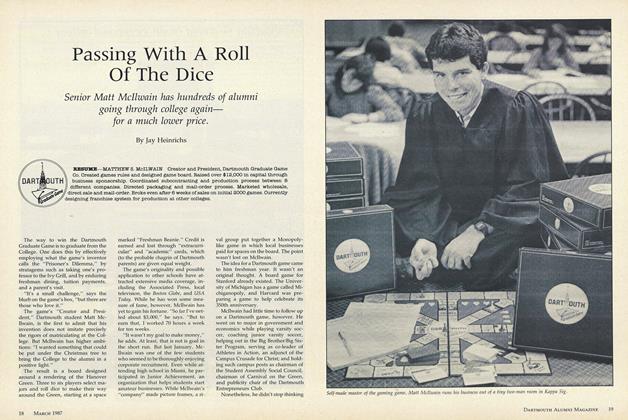

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

MARCH • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE MEDICAL SYSTEM’S EMERGENCY SURGEON

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleThe Dean Of Spin

OCTOBER 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleENGINEERING THE FUTURE

FEBRUARY 1991 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleStatement of Ownership, Management and Circulation (Required by 39 U.S.C. 3685).

OCTOBER 1994 By JAY HEINRICHS -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Night Out on the Net

December 1994 By Jay Heinrichs

Outside

-

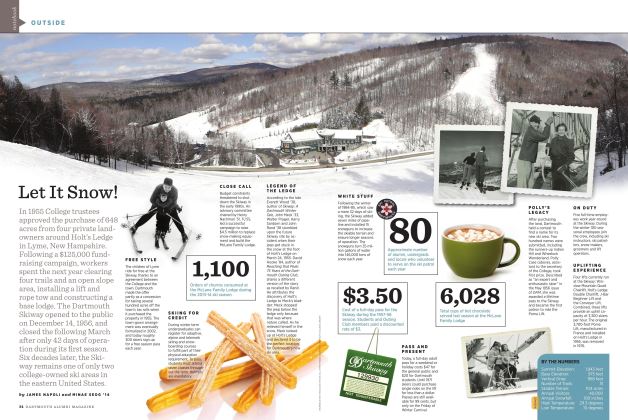

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDELet It Snow!

JAnuAry | FebruAry -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Creek Kid

MAY | JUNE By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEStill Trippin’

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By ED GRAY ’67 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEConfluences

MAY | JUNE 2014 By MICHAEL CALDWELL ’75 -

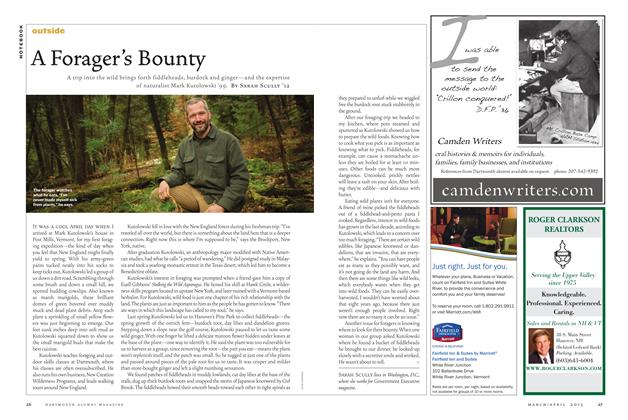

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEA Forager’s Bounty

Mar/Apr 2013 By Sarah Scully ’12 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDENordic Exposure

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2023 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13