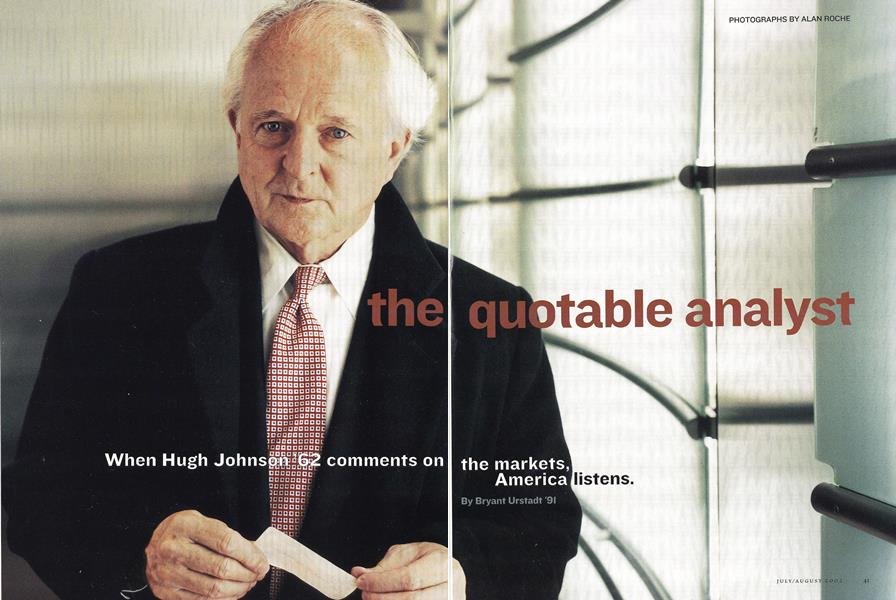

The Quotable Analyst

When Hugh Johnson ’62 comments on the markets, America listens.

July/Aug 2002 Bryant Urstadt ’91When Hugh Johnson ’62 comments on the markets, America listens.

July/Aug 2002 Bryant Urstadt ’91When Hugh Johnson '62 comments on the markets, A merica listens.

It was the first of three appearances Johnson would make on financial news outlets that morning, which is typical for him, when you include print and radio.

"I'm here at CNN every other week," says Johnson, who has blue eyes and a half dome of gray hair. "Then I do Reuters and Bloomberg. Sometimes I fit in CNBC, too, but then I have to go out to New Jersey."

A make-up girl named Jackie has just finished applying a light tan to Johnson. "I get a lot of regulars," she says. "Hughs one of the nicest."

Johnson, 61, is the chairman and chief investment officer at First Albany Asset Management, where he oversees $600 million in portfolios. But he is also one of those cultural oddities: Once someone points him out to you, you start to see and hear him everywhere. I became aware of his ubiquity after about the 10th time my father, Jeffrey Urstadt '62, a classmate of Johnson's, opened the paper or turned on the radio and said something along the lines of, "Hey! There's Hugh!"

If Johnson is not musing on the markets for television, he may be doing a phone interview with NPR's Marketplace or WCBS radio. He can show up in The Wall Street Journal, Money, Barron's, Business Week or The New York Times. Time and USA Today have recently included Johnson in a panel of experts discussing the future of the market.

From time to time he may appear to the American public to have gone to ground. More likely, he is peppering foreign shores with his predictions, for an Australian radio station, for the Agence France Presse or for the paper of record in Slovenia. He is prized by anchors and reporters for the quality of his research and his ability to distill complex events, among other traits. "I talk to him an awful lot," says USA Today reporter Adam Shell. "He can really summarize and capture a week's events very quickly And he'll tell me if things don't look great. He crunches his own numbers and he never goes off the deep end. He's not always saying everything is about to shoot through the sky."

Part of the reason Johnson is so well prepared is that he spends most Sunday afternoons at his home in Albany, New York, kicking back and doing the numbers. "It's like my workbench," he says. "I'll take a report like 'The Consensus Forecast for the Economy,' which surveys 50 analysts, and ask myself: 'What does this imply statistically for corporate profits, short-term interest rates and priceto-earnings ratios?' It's better than watching football."

He may have reached the apex of his quote-giving career on September 17, the first day of trading after the destruction of the twin towers. So many reporters from newspapers and television and radio stations called Johnson for a comment on what it would all mean for Wall Street that he couldn't answer every call, and it has always been a point of pride with him to answer every call. In the green room he does his best to remember whom he spoke with. "Lets see. There was Katie Couric and News Hour, ABC and CNBC, as well as somewhere between five and 10 newspapers," he recalls. "Then there was radio. I didn't know who I was talking to half the time," he says.

Johnson is interrupted when Cafferty calls him over with a friendly, "Hello, Hugh!" and Johnson takes his seat. Once in place, he sits with absolute calm, perhaps because he has been appearing on CNN for about 16 years. He's wearing a navy blue two-button suit from Brooks Brothers, black cap-toe shoes, a white shirt and a red tie with a pattern of little blue squares.

On the air, Cafferty introduces Johnson and says, "Can we read anything into the fact that the markets seemed to fight off the news yesterday?" Johnson can. "Well, there's an old adage—and you have to be careful of old adages—that bull markets climb a wall of worry," he says. He goes on to point out that the leading indicators had been improving, the outlook was positive and that "we're going to see a recovery in the economy and in earnings." Then he was off to Reuters for a 7:30 interview.

Johnson's first major at Dartmouth was economics, fittingly enough. But his major, and his life, changed when he took professor Willis Doney's introduction to 17th-century philosophy. Under Doney (who, according to Johnson, "would have four cigarettes going at any one time. Usually there was one in his hand, one hanging off the desk, one behind his ear and one in the ashtray") Johnson studied the works of Hume, Kant, Berkeley, Descartes and Hobbes. "I immediately switched majors," says Johnson. "He opened my mind to the world of ideas."

His senior year, the head of the department, Francis Gramlich, took Johnson aside after class, telling him, "You simply must study and teach philosophy at a graduate level." Working as a broker on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange Johnson spent five years taking evening classes at New York University toward a doctorate. He never finished. "One night I was sitting with a bunch of guys and we spent a few hours discussing the referencing of the word 'I,' " recalls Johnson. "I realized I needed something different."

But the philosophy stuck with him. "They never mentioned short-selling at NYU," says Johnson. "But philosophy did teach me how to think. It provides one with the tools to approach any subject in a careful, rigorous way."

When he started managing his own firm—Hugh Johnson and Cos.—he hired an associate named Bill Pundman, a star football player from the University of Missouri who had a hearing problem. In 1974 Victor Hillary, a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, called Pundman for a quote. They had difficulty communicating, and Pundman transferred the call to Johnson. A talking head was born. Little changed when Johnson joined First Albany in 1978.

"Of course," Johnson says, "it's not all just fun for me. Getting up at 4 in the morning is real work, but it builds my credibility and it builds the firm's credibility."

As Johnson walks through a pre-dawn

Times Square to Reuters, he remarks, "You have to be a teacher at heart to do this. You have to enjoy taking complex configurations, dissecting them and laying them out in a straightforward way. I used the word 'liquidity' back there. I probably just should have said 'money.'"

At Reuters Johnson is slated to do two segments, one for an Internet broadcast and one for its London-based financial channel. For the online piece, reporter Francesca Segre stands behind a camera and grills Johnson about the long-term effects of the low interest rates and proposed tax cuts Johnson, sitting in a tall directors chair, with the electronic Nasdaq billboard behind him, says, "There's going to be a lot of money out there. Historically, that's led first to recovery and then to inflation."

Margot Risi, the segment producer who books Johnson, is also in the room. "A lot of analysts can give you the surface," she says. "Hugh gives you more levels. His analysis just goes that much deeper. Plus, at this point, he's so widely quoted that he's just got a ton of credibility."

After Reuters Johnson walks up Park Avenue toward a 9 a.m. spot at Bloomberg and offers a lighthearted reason why his predictions, though not "shooting to the sky," do tend to be bullish. "It's a congenital defect," he says. "My father was an optimist. And 70 percent of the time, stocks are rising, so if you're going to guess, you may as well guess up."

Johnson heads up to the Bloomberg studio and sits down by a monitor to wait for his appearance with anchor Dylan Ratigan, host of Moneycast. Ratigan calls him over, saying, "Hugh, can you come on over here, my friend, please, sir?"

Then they are on the air. "How are you?" asks Ratigan. "I'm great," says Johnson.

There is an extremely long pause, while Ratigan searches for some novel twist on the market, which.is not even open yet, and which he has already been dissecting for three hours.

"Um, I'm trying to think of a real good question for you. Because I see you a lot."

"Yeah, the market," says Johnson, trying to be helpful. Ratigan finally breaks through, saying, "Basically, give me...I need action. That's my bottom line. I'm not going to get tricky with you. Tell me what I should do right now."

Johnson has the action. He says he thinks things look positive, recommends a portfolio consisting of 56 percent equities, and suggests moving from value stocks to cyclicals such as Target and Harley-Davidson.

He is done by 9:30. Johnson heads to Grand Central for a train back to Albany, where portfolios await his acumen.

Street Smarts As a student, Johnson (in Times Square) changed his major from economics to philosophy, which provides "tools to approach any subject in a careful, rigorous way," he says.

On a Tuesday not too long ago, just past 6 in the morning, Hugh Johnson '62 was sitting in the green room at CNN's financial news studio near Penn Station, waiting to tell Jack Cafferty, the host of Money Morning, what was going to happen that day.

BRYANT URSTADT is a freelance writer based in New York City. He haswritten for a variety of publications, including Rolling Stone, The New Yorker and The New York Times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Matter of Principle

July | August 2002 By Rick Green -

Feature

FeatureFENG SHUI COMES TO DARTMOUTH

July | August 2002 By ROBERT NUTT '49 -

Outside

OutsideRunning With Wild Abandon

July | August 2002 By Jay Heinrichs -

Interview

Interview“We’ve Got To Go For It”

July | August 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMHeaven and Hell in the Middle East

July | August 2002 By Alex Hanson -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

July | August 2002

Bryant Urstadt ’91

-

Feature

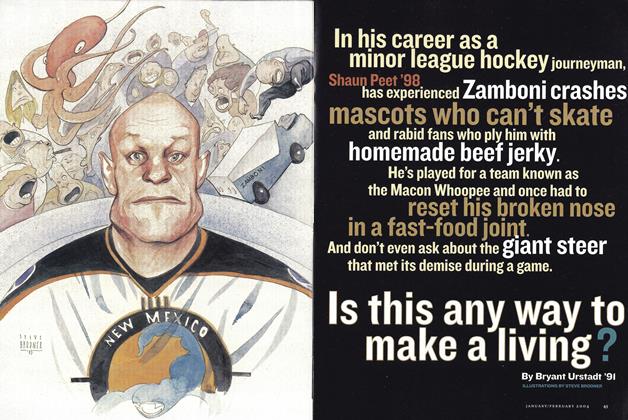

FeatureIs This Any Way to Make a Living?

Jan/Feb 2004 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

FeatureFree Bird

Jan/Feb 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSShrimp, Sirloin, Sass

July/August 2006 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

FeatureCold Warrior

Jan/Feb 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

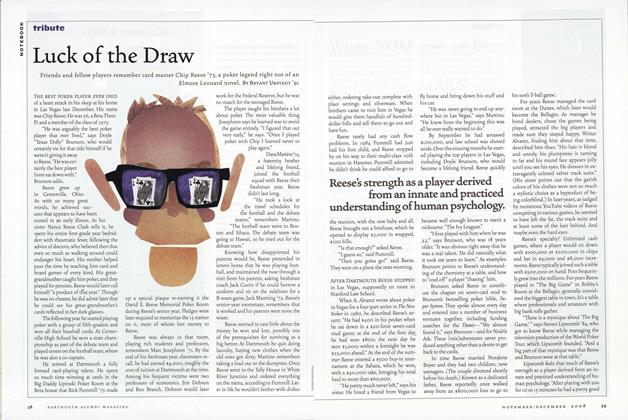

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELuck of the Draw

Nov/Dec 2008 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

FACULTY

FACULTY“This Is Gonna Work”

Sept/Oct 2009 By Bryant Urstadt ’91

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWar Memorial Planned in Center

MAY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureNewly Elected Members of the Alumni Council

OCTOBER 1965 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Started Writing Muscular Prose

OCTOBER 1989 By Chuck Young '88 -

Feature

FeatureADDICTED TO CONVERSATION

MARCH 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

FEATURES

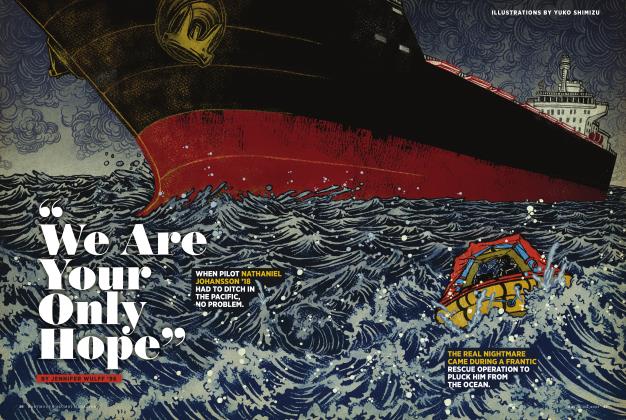

FEATURES“We Are Your Only Hope”

MAY | JUNE 2023 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham