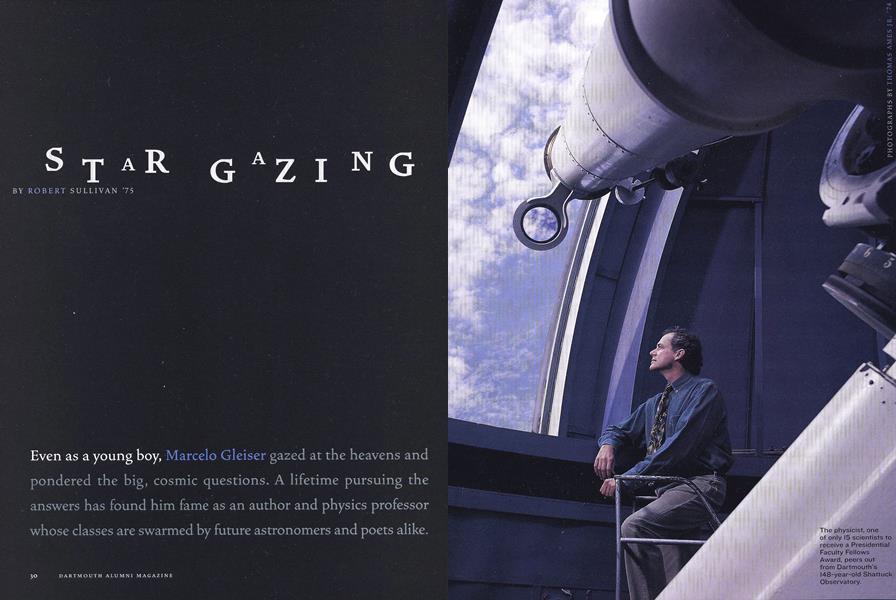

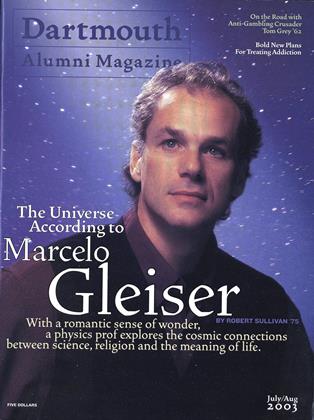

Even as a young boy, Marcelo Gleiser gazed at the heavens and pondered the big, cosmic questions. A lifetime pursuing the answers has found him fame as an author and physics professor whose classes are swarmed, by future astronomers and poets alike.

" The most beautiful and most profound emotion we can experience is the sensation of the mystical. It is the source of all true science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead. To know that what is impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty which our dull faculties can comprehend only in their most primitive forms—this knowledge, this feeling, is at the center of true religiousness." —ALBERT EINSTEIN

Professor Marcelo Gleiser of the physics and astronomy department, one who is famous on campus for blending the clinically scientific and the out-there mystical in his so-called "Physics for Poets" courses—an evangelist who teaches cosmology to engineers, English majors and economists as well as to science geeks-did not feed me that quote. But, indirectly, he led me to it. He inspired me, through his personal and deep passion, to read a little Einstein, plus a little more about Einstein than I had read theretofore. I came across the above passage and said to myself, well, there's Marcelo. That's the whole thing, isn't it? No wonder Einstein's his guy.

"I've got an autographed picture of him," says Gleiser as he sits during a leisurely lunch at La Cote Basque in midtown Manhattan. A youthful 44-year-old Brazilian, he has, on this gray winters day, just come from his literary agent's office where they have been discussing Gleiser's next book, his third, which Gleiser, in a departure, plans as a novel. He is enjoying a tres bon repast and, just now, is talking of Einstein in the reverent tones that my friends and I would use when talking of, say, Ted Williams and the science of hitting a baseball. "My maternal grandfather was one of Einstein's hosts when he visited our country. Einstein would often combine scientific and fundraising trips, the fundraising being for the Zionist movement," Gleiser explains. "My grandfather was a major player in the Zionist movement, and hence the meeting of the two. So when I was 13, I got this autographed picture of him."

The scientist became the young Gleiser's idol. "Einstein may not have been much of a father, which is hard for me because I take fatherhood very seriously, but I admire him a lot in so many other things. His philosophy. He understood that the world was full of mysteries, big questions." Gleiser pauses. "It's all a quest for understanding, isn't it? Einstein knew that. Newton knew it. They never ignored religion, and neither do I. A key theme in my research and teaching is about how structure arises—how something complex comes from something very simple. How such complex, intelligent organisms—us—come from such dumb patterns. Some people might say that sounds like a religious question. Religion has many answers; science has one answer, if you're lucky enough to find it. Science is just trying to understand how nature works; there's no hidden agenda. But isn't it looking at the exact same things- nature,our universe—that religion is?

"Look, if you're only going to discuss Newton as a scientist, you're missing it."

The interplay and tension among institutionalized religion, the mystical, the mythical, physics and cosmology are hallmarks of Gleiser's teaching and writing—indeed, his being—and it has been working on him since his boyhood. Those youthful years were spent in Rio de Janeiro, which bequeathed him an accent, a hint of which is still in evidence now, 18 years after he landed on American soil. How Gleiser's family came to host Einstein in Rio is an interesting tale, rendered here in shorthand.

"My family's was a typical Eastern European Jewery immigration story," Gleiser says. "They were Ukrainian and escaped after the Bolshevik Revolution. The ship they were on came to Ellis Island, but quotas had been filled by 1923 and—poof—the whole boat went down to South America. My paternal grandfather Jacob Gleiser, started his life in South America playing piano in silent movie theaters in Sao Paulo, then made his fortune as a salesman and an entrepreneur. He was into everything: carpets, then a TV factory, even a bank."

The family established itself in Rio and was quite well off. Says Gleiser: "Except for the fact that in the 1970s I was a real Copacabana boy—beach volleyball, all that stuff—my story was similar to those of most New York Jews: an intellectual house, expected to excel in school, a lot of music, two or three languages. I started playing guitar when I was 12 and still love to play. I loved classical, popular jazz, Brazilian music. I was definitely drifting toward music."

It is supposed, retrospectively, that no matter what endeavor the bright,young Gleiser poured himself into, he might have found success. As it happened, Bossa Nova's loss was physics' gain. "I loved music but also found that I was most fascinated by big questions, metaphysical stuff. What about life after death? My mother had died when I was 6, so I knew loss. I liked vampires, things that could live forever. By the time I was about 10 I had already grown very disappointed by religion, especially by the bloody history of religion. I needed another answer. I was given one of these big illustrated books, something called, like, The Complete Natural History. And there it was: science, a rational light.

"Now, there are two kinds of scientists, the algebrists with their deductive logic, and the geometers, with their spatial intuition. I found I was much more the second kind, and learned later that I was in good company. Einstein was like that, too."

In the modern age, the education of a prodigy is the worlds business. It was academes highways (or flight paths) that carried Gleiser out of Rio to, first, London, where he got his Ph.D. at King's College in 1986, thence to the American Midwest. "I went to Fermilab in Chicago during my lastyear as a student. My original plan was to finish my Ph.D. and go back to Rio, as did the vast majority of Brazilians studying abroad. Then at Fermilab,wherel was part of the theoretical astrophysics research group—working on very mathematical theories that tried to unify all forces of nature—I was offered a post-doctoral fellowship that I couldn't refuse. My plan shifted to, 'l'll stay as long as it works out.' " He met his first wife in the Windy City, and their family would grow to include two sons and a daughter. Gleiser s next posting, from 1988 to '91, was at the University of California at Santa Barbara, and then he signed on at Dartmouth as an assistant professor.

During all this time of learning and research, he was finding himself—his vision, his voice—within his chosen field. He still enjoyed mulling the biggest questions, and he wrestled with what a scientist might term the Sagan Imperative, which maintains that science is, by nature, godless. Formal religion had already let Gleiser down, and yet he retained a romantic sense of wonder. "Obviously, in my field, Carl Sagan was a big person," says Gleiser. "And I admire a lot of his work. But there was a bad side of him, I think, in this dogmatism, the anti-religion crusade he had. I'm not any kind of religious person—I don't believe in God—but I think a key attitude that a scientist should have is doubt. We can get all the way back to the instant of the Big Bang but we can't know that instant—and I'm happy we don't know it, the true source of origin. God can be seen at the gaps; the wiggle room is in the questions. What is the mind? What is the soul? Is there a purpose in life? It's as Kundera said: The key questions are the ones, children ask. And many have no answer."

Make no mistake: Gleiser is as adept at answering the direct questions as he is at posing the big, woozy ones. As a science professor he must be, and to his hardcore physics freaks, such as those in his advanced graduate course on the physics of the early universe, which involves not only particle physics but cosmology and statistical mechanics, he explains the nuts and bolts. But to the poetically inclined masses who flock to his interdisciplinary science/ social science courses, co-taught with history department colleague Rich Kremer, it is Gleiser's metaphysical approach that is alluring. "It's hard to find a scientist who is skilled at being able to communicate complicated ideas to a non-scientist," says Kremer, Gleiser s co-conspirator in the introductory courses, which look at the physical world along with creation myths, the rise of nations and other matters relating to the human condition, presenting science as part of an evolving cultural process, as a search for a deeper understanding of the world around us. The courses are always fully subscribed at around 180 students. "Scientists can easily lose an audience, and Marcelo gets that point. So in our classes he will always use visual materials, he will draw a diagram or a picture to illustrate a very large point, and this proves a marvelous way for undergraduates to follow him wherever he's going.

"And we'll debate," adds Kremer. "We both want to be in the classroom all the time, even if it's the other guy's turn to lecture. If one of us makes a bad mistake or phrases a question the way only a scientist or historian would, then the other might interrupt and rephrase it, or challenge the point. Marcelo and I understand one another very well, so it's all fun. The subject comes alive."

Prior to 1994, Gleiser's renown was effectively bounded by the Upper Valley. But in that year Gleiser experienced a personal Big Bang when his application to the National Science Foundation led to the Clinton administration naming him a Presidential Faculty Fellow. That's a truly hotshot award, and it put Gleiser on the mapon both sides of the equator.

"That changed a lot of things for me," Gleiser says. "It was a huge surprise. I'll tell you, it was big on campus, but it was really big in Brazil. They hear 'President Clinton' and it's, like, 'Wow!' TV cameras started showing up to get interviews for stations back home. When I went back there, I found out how big the whole thing was to them." As Gleiser suggests, he began to exist on two planes, as if he were caught in some weird cosmological warp. He was a "Yo, Marcelo!" celebrity on the streets of Rio—the Carl Sagan of Brazil, which isn't exactly like being the Pele of Brazil, but neither is it chopped liver—yet he was living in a sleepy place called New Hampshire, somewhere north of Boston in a country that will grant anyone 10 minutes of fame, but only the privileged few their full 15.

Gleiser found, during his regular trips to the homeland, that he didn't mind his new stature in Brazil one bit. In fact, it could be useful in forwarding his ideas. He did what any modern-day breakout college professor might do: He got himself a TV show, and wrote himself a book. Scientists and Food Channel marketers alike might call this the same thing: the Julia Child Phenomenon, i.e. the medium is the maker of what the person is, in the public consciousness. Before Julia, cooks worked in the kitchen, not on television. Today, of course, if you're not on the Emeril/Mario/Bobby Network, you're no kind of chef—not really. Vis-a-vis science, the Julia-sized pioneers have been Sagan and Stephen Hawking, the latter of whose famous public television series featured prominently, in Episode Three, this latest wunderkind named Marcelo Gleiser. "I talked about a big puzzle of physics," Gleiser says. "I was talking about why there is more matter than antimatter in the universe. According to the laws of physics, they should appear in equal parts. But if they did, we wouldn't be here to ask questions. So we are a consequence of some fundamental imperfection in the cosmos, a slight excess of matter over antimatter. The question is: What caused this imperfection?" PBS Nation lapped up the arcana like milk.

If Gleiser was getting a little airtime to ask his big questions in this hemisphere, he was becoming an action hero to South American adolescent physics jocks via a weekly kid-friendly science show called Globo Ciencia. And when his first book for a lay audience, TheDancing Universe: From Creation Myths to the Big Bang, was published in Portuguese in 1997, it sold 20,000 in its first two months, storming Brazil's bestseller lists.

It was well-regarded in North America, too, in its English-language version. As was Gleiser's second book, published last May, which was a sequel of sorts titled The Prophet and the Astronomer:AScientific Journey to the End of Time. Gleiserwas establishing himself as an egghead who could parse cosmology in a comprehensible fashion, a go-to guy for beat writers and NPR whisperers who needed a nifty—and informed—soundbite. He wrote as he taught, engagingly, and with a large store of metaphors: "A small fraction of a second after the 'beginning,' many kinds of particles and their antiparticles, in equal amounts, roamed about and collided with each other in tremendous heat, as in a cosmic minestrone soup." In the mold of Sagan, Hawking and the recently deceased Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, he was busily proving that a scientist can have it both ways. He can reach out to the laity and still be, at bottom, a serious guy. Consider: His books have found a general, not to say pop, audience, while his essay "Emergent Realities in the Cosmos," concerning British philanthropist and promoter of a science-religion exchange John Templeton Strong, was recently selected by editor Oliver Sacks for the anthology Best American Science Writing 2002.

Gleiser s life is not without its disappointments. Professionally, he was unhappy when a proposed deal for a PBS presentation of The Dancing Universe fell through. Personally, he was distressed that his first marriage failed, not least because he is overarchingly passionate about his role as a father. These days he flies from Manchester to Chicago regularly throughout the year to see his kids, who live with their mother.

In October 1998 Gleiser remarried. His wife, Keri, once signed up for a Gleiser course—she's Dartmouth class of '97—and now has signed on for life. That life will be spent in Hanover and Plainfield, where the couple recently completed work on a house of their own design. "It's Maxfield Parrish country; you can see Mt. Ascutney from our place," says Gleiser. "It was remarkable how we found the land. We were out apple picking, and there was this wonderful piece of land, 12 acres, that seemed perfect. Turned out it was available. Remarkable." Gleiser never uses the word miraculous. "We love it here. We cross-country ski, we walk. We camped out a little while back, and actually saw the aurora."

If his nights are spent gazing at—and no doubt contemplating—the heavens (if not Heaven), then his days are spent teaching and his evenings, writing. He is hard at work on the third book, which he has, on this winter afternoon in New York City, just told his new agent that he intends as a fiction based on the life of 17th- century German astronomer Johannes Kepler. Gleiser is asked if he has read the acclaimed John Banville novel, Kepler. "Yes," he says, "but I didn't think it was good. He's not a scientist. I hope to do a better book. I've been spending a large part of the winter writing— or trying to—my Kepler, and it's been a wonderful but very demanding task. Fiction is very tough."

There is the sense, always in the margins of the conversation, that Gleiser would happily embrace a Brazil-sized media success in the States. He speaks of how he recently took part in a forum where he met Dava Sobel, whose Longitude was an astonishing bestseller in 1995. "It was a literary evening at the Cornelia Street Cafe in Greenwich Village," Gleiser says. "It was on the subject of 'translation.' Dava spoke about translating letters from Galileos daughter, and I spoke about how science can be viewed as a translation, away of humanizing the workings of nature.

"Davas really something," Gleiser adds admiringly. It's amazing what's happened to her." A U.S. success along the lines of Sobers would not be unwelcome.

Should it come, Gleiser will use it for what he perceives as good: doing the translation, bringing science to the masses, helping ever more people wrestle with—embrace—the big questions, the ones he so loves to confront, the ones Einstein felt were "the center of true religiousness." Gleiser is asked, as a long, stimulating lunch nears its end, which courses he prefers to teach, the hardcore or the soft. He considers for a moment, and smiles slightly, "Nowadays, I get more pleasure talking to my poets. It's more of a challenge. The other guys, they speak the language. With the poets, it involves a double translation. That makes life more interesting."

The physicist, one of only 15 scientists to receive a Presidential Faculty Fellows Award, peers out from Dartmouth's 148-year-old Shattuck Observatory.

Gleiser plans to follow up the success of his two nonfiction books with a novel about 17th-century astronomer Johannes Kepler.

ROBERT SULLIVAN is the editor of LIFE magazine and LIFE Books.

"I'm not any kind of religious person- I don't believe in God—but I think a key attitude that a scientist should have is doubt."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDinner at Dartmouth

July | August 2003 -

Feature

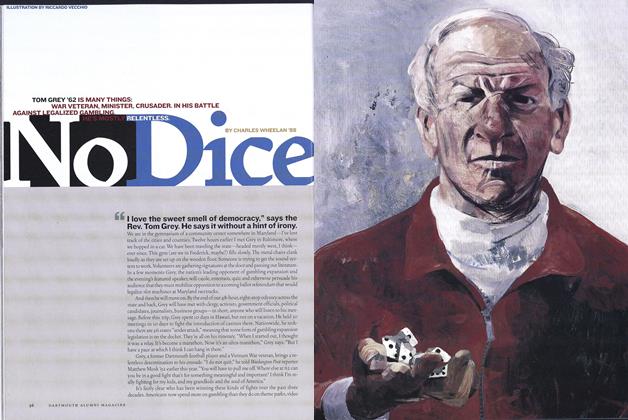

FeatureNo Dice

July | August 2003 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

July | August 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Article

ArticleThe Big Day

July | August 2003 By Julie Shane '99 -

Article

ArticleFighting Addiction

July | August 2003 By Julie Sloane '99 -

Interview

Interview"A Diversity of Ideas"

July | August 2003 By Karen Endicott

ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

-

Sports

SportsFifty-one Minutes

May 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Higher-Ed Book Biz

JUNE 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleDuke's World Revisited

June 1993 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySanta: The Dartmouth Connection

DECEMBER 1996 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

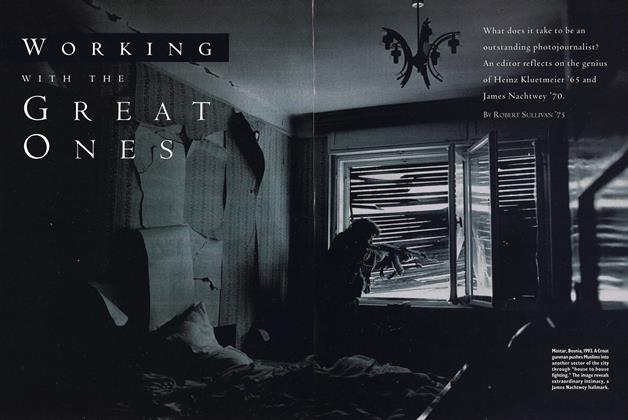

ArticleWorking with the Great Ones

JUNE 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

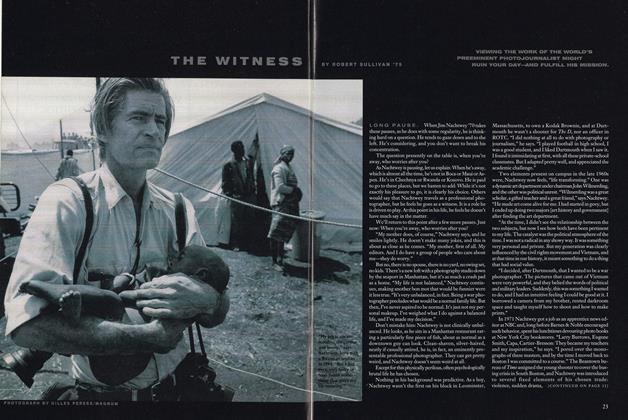

Cover StoryThe Witness

JUNE 2000 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

Features

-

Feature

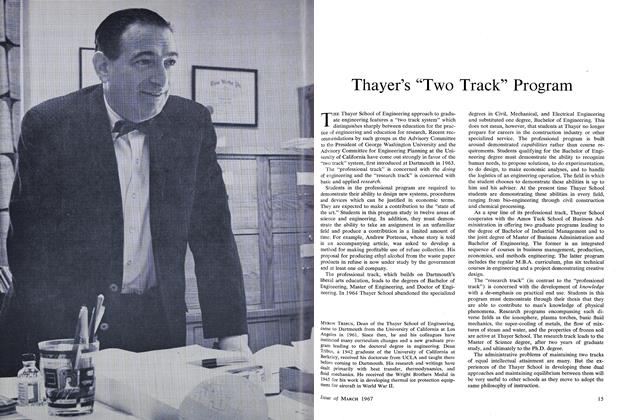

FeatureThayer's Two Track Program

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Debaters Are Arguing Themselves Into National Renown

March 1962 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Cover Story

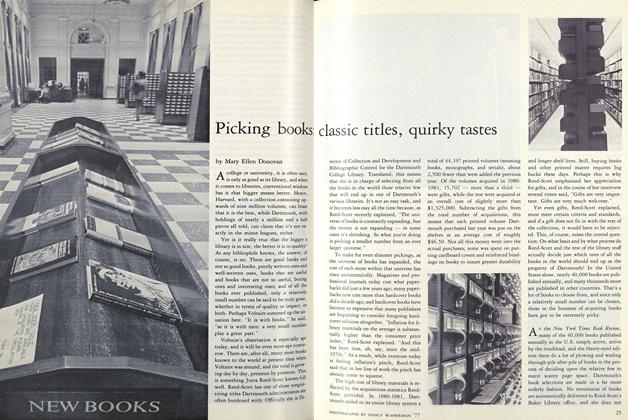

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

MARCH 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureQuebec in the Modern World

JULY 1964 By THE HON. JEAN LESAGE, LL.D.