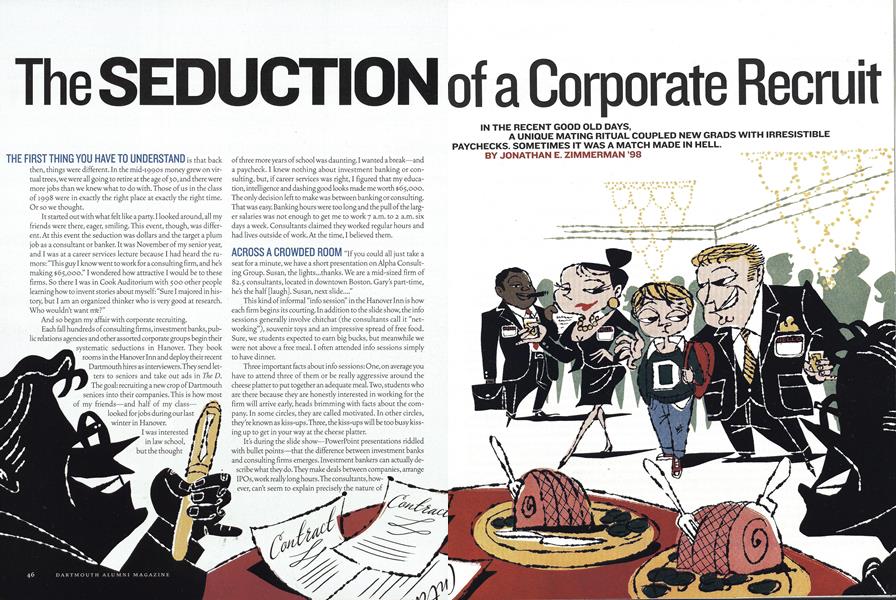

The Seduction of a Corporate Recruit

In the recent good old days, a unique mating ritual coupled new grads with irresistible paychecks. Sometimes it was a match made in hell.

Sept/Oct 2003 JONATHAN E. ZIMMERMAN ’98In the recent good old days, a unique mating ritual coupled new grads with irresistible paychecks. Sometimes it was a match made in hell.

Sept/Oct 2003 JONATHAN E. ZIMMERMAN ’98IN THE RECENT GOOD OLD DAYS,A UNIQUE MATING RITUAL COUPLED NEW GRADS WITH IRRESISTIBLEPAYCHECKS. SOMETIMES IT WAS A MATCH MADE IN HELL.

THE FIRST THING YOU HAVE TO UNDERSTAND is that back then, things were different. In the mid-1990s money grew on virtual trees, we were all going to retire at the age of 30, and there were more jobs than we knew what to do with. Those of us in the class of 1998 were in exactly the right place at exactly the right time. Or so we thought.

It started out with what felt like a party. I looked around, all my friends were there, eager, smiling. This event, though, was different. At this event the seduction was dollars and the target a plum job as a consultant or banker. It was November of my senior year, and I was at a career services lecture because I had heard the rumors: "This guy I know went to work for a consulting firm, and he's making $65,000." I wondered how attractive I would be to these firms. So there I was in Cook Auditorium with 500 other people learning how to invent stories about myself: "Sure I majored in history, but I am an organized thinker who is very good at research. Who wouldn't want me?"

And so began my affair with corporate recruiting.

Each fall hundreds of consulting firms, investment banks, public relations agencies and other assorted corporate groups begin their systematic seductions in Hanover. They book rooms in the Hanover Inn and deploy their recent Dartmouth hires as interviewers. They send letters to seniors and take out ads in The D. The goal: recruiting a new crop of Dartmouth seniors into their companies. This is how most of my friends—and half of my classlooked for jobs during our last winter in Hanover. I was interested in law school, but the thought of three more years of school was daunting. I wanted a break—and a paycheck. I knew nothing about investment banking or consulting, but, if career services was right, I figured that my education, intelligence and dashing good looks made me worth $65,000. The only decision left to make was between banking or consulting. That was easy. Banking hours were too long and the pull of the larger salaries was not enough to get me to work 7 a.m. to 2 a.m. six days a week. Consultants claimed they worked regular hours and had lives outside of work. At the time, I believed them.

ACROSS A CROWDED ROOM -if you could all just take a seat for a minute, we have a short presentation on Alpha Consulting Group. Susan, the lights...thanks. We are a mid-sized firm of 82.5 consultants, located in downtown Boston. Gary's part-time, he's the half [laugh]. Susan, next slide...."

This kind of informal "info session" in the Hanover Inn is how each firm begins its courting. In addition to the slide show, the info sessions generally involve chitchat (the consultants call it "networking"), souvenir toys and an impressive spread of free food. Sure, we students expected to earn big bucks, but meanwhile we were not above a free meal. I often attended info sessions simply to have dinner.

Three important facts about info sessions: One, on average you have to attend three of them or be really aggressive around the cheese platter to put together an adequate meal. Two, students who are there because they are honestly interested in working for the firm will arrive early, heads brimming with facts about the company. In some circles, they are called motivated. In other circles, they're known as kiss-ups. Three, the kiss-ups will be too busy kissing up to get in your way at the cheese platter.

It's during the slide show—PowerPoint presentations riddled with bullet points—that the difference between investment banks and consulting firms emerges. Investment bankers can actually describe what they do. They make deals between companies, arrange IPOs, work really long hours. The consultants, however, can't seem to explain precisely the nature of their work. They will say that they "create value-added studies and analyses for clients in a wide range of industries." Or they "provide a necessary outside perspective on the cutting-edge management issues facing todays Fortune 500 companies." Or they "use a system of proprietary and industry-specific frameworks and tools developed during years of experience to provide synergistic and complementary strategy-formation aid to their clients." Whatever they do, every consulting firm in America apparently has a unique, warm, friendly corporate culture in which you'll get paid a lot to work on really interesting problems for a few hours a day with the attractively suited people making the presentation.

After taking questions, the speakers hand out "info packets" full of glossy brochures that explain why you'd want to work for this consulting firm. Often, the packets include a squeezable "stress ball," a Frisbee or pens stamped prominently with the company's logo. These objects quickly become a way of ranking the companies. Beta Consulting gave out umbrellas, while Delta Consulting only gave out pads of paper. Clearly, Beta is the better place to work.

THE FIRST DATE My first interview was with a company that, for the purposes of anonymity, I will call D&C. It was a small Washington,D.C., firm, and rumor had it they paid New York City salaries. I wanted to do a good job in this interview as I felt it would set the tone for the rest of the recruiting season.

Too nervous to sit around my house, I left 45 minutes before I needed to be at my interview even though I lived only 10 minutes away. I lived at the bottom of a hill; since it had snowed the night before, that hill took quite a bit of conquering. Dress shoes don't exactly grip. By the time I arrived in the warm lobby of the Hanover Inn I was thoroughly soaked from both snow and the sweat of exertion.

The elevator ride to the third floor allowed me time to adjust my tie. The doors opened, I took a deep breath, found Room 315 and stepped into the reception area of a nice suite. The firm's human resources person was happy, genial and really good at making conversation. There was a smattering of the younger and more attractive associates (generally recent alums), the other students interviewing that day—and food. The food spread was really impressive, with sandwiches, cookies and drinks. Despite how attractive these trays are, they never get touched. Think about it. When you're about to go into an interview, do you want cookie crumbs between your teeth? Do you want to risk spilling fresh-squeezed orange juice on your only suit?

The interviewees sit in the reception room like a group of people waiting for elective surgery. One at a time they disappear with their interviewers. Interviewees are summoned in one of two ways. In the first, the interviewer walks the interviewee to the interview room. The other option is my favorite. The phone rings in the greeting room, the human resources person answers it, turns to the interviewee and says, "So and so is ready for you now. She's in room blah blah blah." I liked this because I felt as though I was the relief pitcher called from the bullpen to save the game. Either way, the interviewee ends up in another nice hotel room, this time alone with the interviewer and a huge four-poster bed.

The bed became a strange recurring presence during interview season. Imagine being locked in a cozy room alone with a very attractive consultant (since the consulting firms tended to send the most beautiful to interview) and a huge bed. Of course nothing ever happened, but the bed was almost uniformly considered an unwelcome and uncomfortable presence.

The interviewer offers more food and drink, which of course the interviewee declines, and then the interview begins.

Consulting interviews are one of two types, the "personality fit" or the "case interview." The personality fit consists of talking about your resume and yourself. This requires some idea of why you want to do consulting, or at least a good answer to that question. A consultant I knew told me to think of these interviews as the "airplane test." The interviewer is asking himself if he could sit next to you on a flight from Boston to L.A. without wanting to use the emergency exit.

Case interviews can be subdivided into two types: the brain teaser and the business case. The brain teaser requires doing a lot of math in your head. In one interview I figured out how many laundromats there are in the United States. I started with the population and made estimates based on percentages I invented for people who don't own washing machines, don't live in buildings that have washing machines and don't dry clean all their clothes. I was within 10,000 of the real number, which totaled into the hundreds of thousands. When I expressed happiness at how close I was, my interviewer said only: "But you were off."

I preferred the business case interviews because there was no math involved. Here's an example: "A major European company wants to open a bunch of stores to compete with Home Depot. They want to know why Home Depot has been so successful. What do you tell them?" "People want to buy home goods and Home Depot provides them more cheaply than their cometitors," you say. The interviewer says, "Good, but tell me how Home Depot can do that?" "Well, they can do it because they buy in bulk, they can spread costs around," you say. "Very good," the interviewer says.

I'll spare you the rest.

WAITING BY THE PHONE After the interview the interviewee returns home to wait around for the firm to call him that night to tell him if he will advance to a coveted second-round interview the next day. Second-round interviews are essentially the same thing as the first round, only longer and often with more difficult cases. The calls were amusing in my house because a roommate and I interviewed with many of the same firms. It was not uncommon that an interviewer would call to reject one of us ("Sorry, you seem like a great guy but we just aren't sure your analytical skills are on the level we are looking for") and call back 10 seconds later to accept the other. We liked to disturb the caller by having the rejectee answer the second phone call sounding profoundly depressed.

GETTING SERIOUS Two weeks into my interviews, the process took on a life of its own. At first I was having three or four first-round interviews a week. With second-rounds added in, it became one or two interviews a day. Since I only owned one suit, keeping it clean was a task. The hectic interview schedule forced me to wear the suit to class on numerous occasions. Most faculty didn't seem to notice. A few, particularly English professors, scowled and made disparaging remarks about the "so-called profession of consulting." My fellow recruits and I took such comments in stride, realizing that much of the disdain stemmed from the fact that we would be paid more in our first year after college than a first-year professor with a Ph.D. would get teaching in a tenure-track position at Dartmouth.

I wish I could claim that with the constant practice I got better at interviewing, but I cannot. I am not good at doing math in my head. I knew that in each interview I would eventually be outed as the mathematically impaired history major that I was. I devised ways to delay the inevitable. I would talk as much as possible about my resume, and whenever the interviewer looked at his watch I would begin another story to avoid the line "So why don't we try a case, which usually signaled my downfall. During one long day I blew two first-round cases before ending up in a second-round interview with a difficult case. After working through all the theory and setting up the basic problem I arrived at an answer of 365 divided by 15. The interviewer smiled and said, "Right, so what is it? I responded, "It's 365, divided by 15." "Yes," she said, "but what number is that?" at which point I exhaled deeply and said, To tell you the truth, I have no idea. This is my third interview today and if you want to know what 365 divided by 15 is, you're gonna have to give me a calculator." Strangely, this worked. That night I was offered a final-round interview with the same firm.

The mystical final round is the most coveted interview of all. The lucky interviewee is flown, at the company's expense, to the firm in question and put up overnight at an establishment such as the Ritz Carlton in Boston or the Plaza in New York. A final-round interview is actually six or seven interviews spanning a day. Most are personality-fit interviews, but a few are reserved for cases.

Many final-round interviews include lunch, and occasionally dinner, with employees of the company. These meals are painful, awkward experiences, similar to dining with a blind date who has brought along her parents. Conversation tends to be stilted. The experience, however, can be educational. If the employees check their watches every five minutes or answer their cell phones at the table, the interviewee can get a sense of how many hours a day the work really requires. If the employees drag the lunch out for hours, the interviewee might want to make sure this company has enough clients to keep it afloat.

WE HAVE TO TALK I ended up working for a small Bostonbased consulting firm. I got the job apparently because each person I interviewed with thought that someone else was doing the case interview. I finally learned what consultants do: anything a client is willing to pay them enough money to do. I worked on a variety of projects for Fortune 500 companies. For the leading U.S. manufacturer of microfilm-related products I established just how many microfilm reader-printers there are in the libraries of America. (During one research interview, a librarian at a U.S. military base in Rhode Island told me that my job sounded "boring.") For a billiondollar, multinational corporation I figured out exactly how many engineers to fire from the American sewage subsidiary it was downsizing. That made me feel great about my job. And in the crowning jewel of my consulting career, I produced, for a manufacturer of wigs, a business model that showed them how many American men are bald and, of those, how many could be expected to buy toupees, take hair-replacement drugs or have hair-replacement surgery. I called this the Rugs, Drugs or Plugs Model.

Sometimes I liked my job. Sometimes I found it challenging and occasionally rewarding. I learned a lot about how to operate businesses. But there was none of the glamour promised by the recruiting brochures. Instead, I stared at spreadsheets for long hours in a windowless cubicle. I found I missed books and complete sentences. I lasted less than a year.

I did, however, make $65,000.

Jonathan E. Zimmerman lives with his wife, May a Lodish '98, inBaltimore. He is currently a law clerk for Thomas Penfield Jackson '58 onthe U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

"An important fact to know. about info sessions: The kiss-ups will be too busy KISSING UP to get in your way at the cheese platter."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Golden Return

September | October 2003 By JOHN GROSSMAN ’73 -

Feature

FeatureO Julie!

September | October 2003 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

September | October 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Outside

OutsideGetting the Ax

September | October 2003 By Lisa Gosseling -

Student Opinion

Student OpinionLet the Hype Begin!

September | October 2003 By Kabir Sehgal ’05 -

Article

ArticleBack Where It Belongs

September | October 2003 By Alice Gomstyn '03

Features

-

Feature

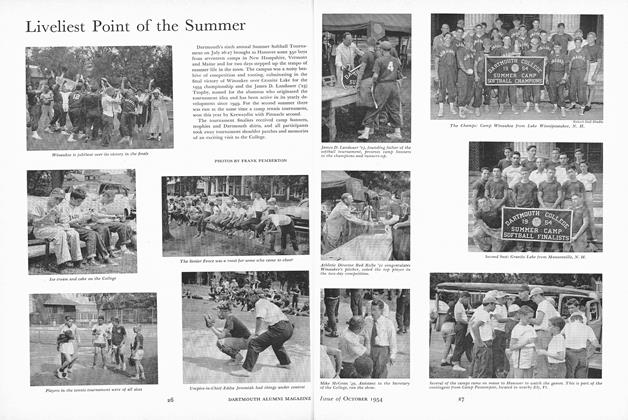

FeatureLiveliest Point of the Summer

October 1954 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Hear 1970 Called "Great Year for Dartmouth"

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Feature

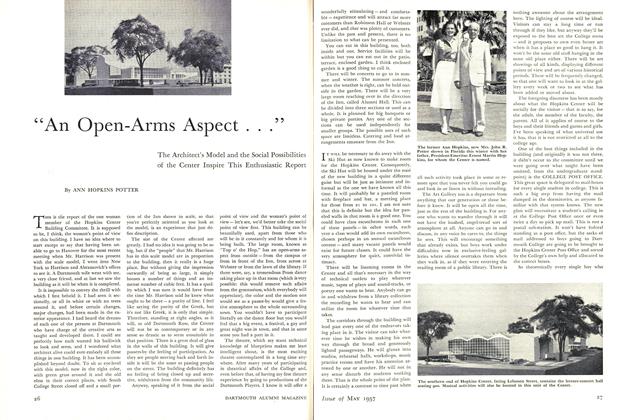

Feature"An Open-Arms Aspect ..."

MAY 1957 By ANN HOPKINS POTTER -

Feature

FeatureNo Ordinary Joe

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2018 By EMILY ESFAHANI SMITH ’09 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Master's Reply

MARCH 1995 By Giegerich '51 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Overtreated American

Nov/Dec 2003 By SHANNON BROWNLEE