The (mixed) blessings of living in Hanover.

An old adage says that Dartmouth students spend four years trying to get out of Hanover and the rest of their lives trying to get back. Many succeed; 1,266 alumni live in the Upper Valley year-round, and countless others own second homes in the! area. Clearly, Mater doesn't suffer from the empty nest syndrome.

One attraction is Hanover's increasing accessibility to the outside world. Dartmouth is in the center of an uncrowded resort area that lies just two hours from Boston (by highway) and an hour from New York (by either of two well-run commuter airlines). This combination of rural beauty and urban accessibility, says a local filmmaker, qualifies the Upper Valley as a "suburban wilderness."

The College itself is a magnet, of course. Unlike many schools, Dartmouth welcomes the community to the campus for events ranging from a preschool arts program at the Hopkins Center to open lectures by the likes of Saul Bellow. Other public perks subsidized by Dartmouth include programs in film, music, drama and dance, as well as day care and free admission to the Hood Museum.

The place is retirement heaven; the over-65 set is the fastestgrowing age group in town. Rand McNally's "Retirement Places Rated" recently ranked Hanover among the best places in the nation to end up. Factoring in such benefits as medical care and outdoor activities, the guide declared the town's quality of life to be superior to such better-known (and decidedly warmer) retirement havens as Miami, Sarasota and Chapel Hill.

But alumni don't have to wait that long to return. A booming economy with the nation's lowest unemployment rate offers a wealth of opportunity—provided you're willing to setde for less-than-stratospheric salaries.

The influx of professionals and retirees has profoundly affected the economics and character of the Upper Valley. The U.S. Census Bureau says the region is growing about 40 percent faster than the national average. William Hamilton, a trust officer at the Dartmouth National Bank, notes that with few exceptions his clients have moved to the area from out of state. (Few local residents ever amass a fortune big enough to require trust services.) About half the banker's customers are Dartmouth alumni, the majority of whom have a net worth of at least $1 million.

Even the local culture is changing. Not so long ago, Gallo was the most exotic wine on grocery shelves and finding a Sunday Times took longer than reading it. Today, Bordeaux and brie compete for space in the general stores alongside such staples as flannel shirts and fishing tackle.

The area is also experiencing a real estate boom, which creates problems for middle-class settlers. Most lots within site of Baker Tower boast bigcity prices. Speaking about the popularity of Hanover among wellheeled retirees, President Freedman told the New York Times, "Of course we welcome them all, but they have made it all but impossible for junior faculty and younger professors to find affordable housing near campus. As a result, instructors and younger professors are having to live as far as 20 miles away, and this is not good for them or for Dartmouth because it interferes with the growth of a closely knit faculty."

Professors are not the only ones who have trouble coming to Hanover. After all, even paradise has its price. There are other factors to consider as well. The editors have examined a few of them including real estate, taxes, health care and employment prospects.

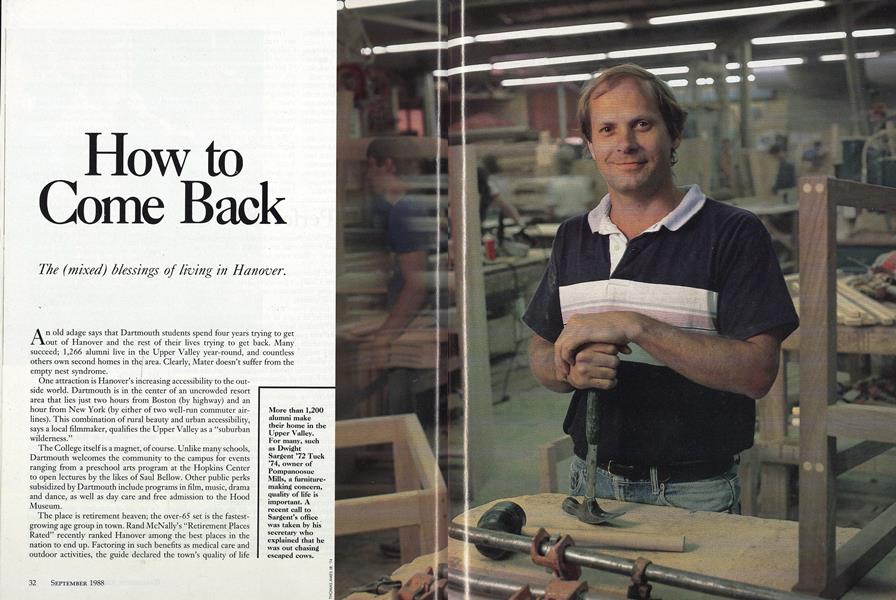

More than 1,200 alumni make their home in the Upper Valley. For many, such as Dwight Sargent '72 Tuck '74, owner of Pompanoosuc Mills, a furniture-making concern, quality of life is important. A recent call to Sargent's office was taken by his secretary who explained that he was out chasing escaped cows.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWelcoming the Loner

September 1988 By Victor F. Zonana '75 -

Feature

FeatureFrom America's Lost Cohort, the Shards of Souls

September 1988 By David R. Boldt '63 -

Feature

FeatureIn the Galactic Search for Intelligence, We May Find Ourselves

September 1988 By Jack Baird -

Feature

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

September 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Sports

SportsFall Sports Preview

September 1988 -

Article

ArticleRush Delayed

September 1988 By Jack Steinberg '88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

MARCH 1964 -

Feature

FeatureNugget to Times Square

January 1974 -

Feature

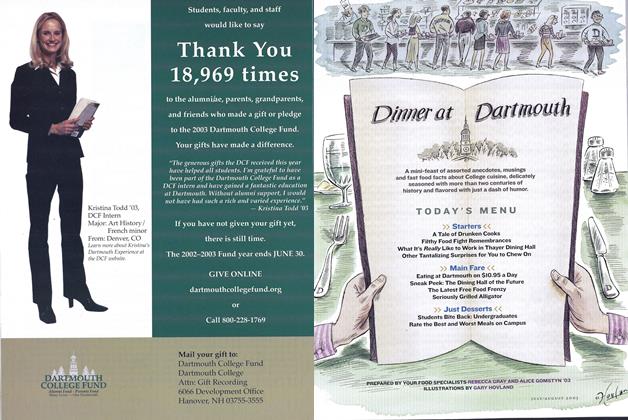

FeatureDinner at Dartmouth

July/Aug 2003 -

Feature

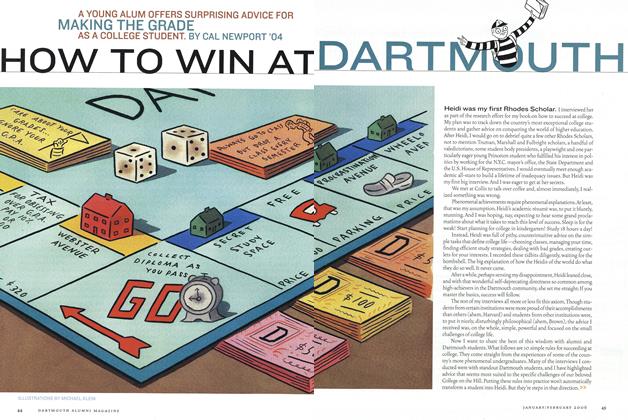

FeatureHow to Win at Dartmouth

Jan/Feb 2006 By CAL NEWPORT ’04 -

Feature

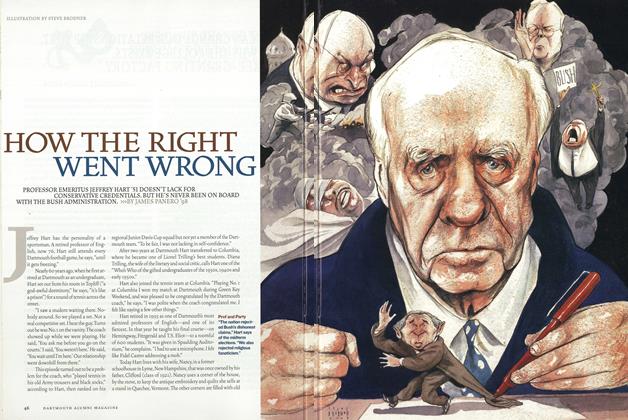

FeatureHow the Right Went Wrong

Jan/Feb 2007 By JAMES PANERO ’98 -

Cover Story

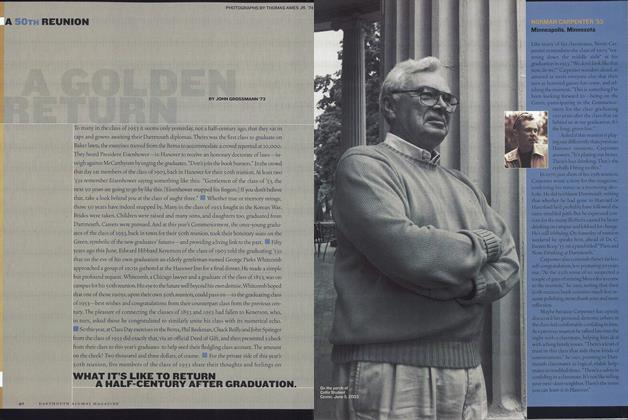

Cover StoryA Golden Return

Sept/Oct 2003 By JOHN GROSSMAN ’73