Slow Medicine

A Dartmouth geriatrician offers insight into a new prescription for eldercare.

May/June 2009 Dennis McCullough, M.D.A Dartmouth geriatrician offers insight into a new prescription for eldercare.

May/June 2009 Dennis McCullough, M.D.A Dartmouth geriatrician offers insight into a new prescription for eldercare.

A JAPANESE FILM I SAW YEARS AGO tells the story of three generations living in extreme poverty on a remote northerly island that afforded its residents neither doctors nor anything beyond the simplest folk remedies. Life was hard. Food was scarce. When an aging grandmother recognized it was her time to die, she broke her teeth with a stone so there could be no arguing about her eating the family’s food. Reluctantly, inexorably, the old woman weakened. Finally her loving and dutiful son was forced to undertake the community’s arduous tradition of carrying his mother on his back to the top of a steep and holy mountain, where she would be laid out with other frail elders to die a peaceful death by falling asleep in the freezing snow. The son’s balance, strength and grip occasion- ally failed. Engaged in their shared ritual, parent and child seldom spoke except to acknowledge their mutual trust and the difficulty of their task.

Those caring for aging parents to- day find their journey up that figurative mountain equally difficult and consider- ably longer, even with the ample benefits and miracles of contemporary medicine. There’s no getting around the inevi- table necessity for physicians and fami- lies alike to undertake the care of aged loved ones during months, or even years, of decline and on through the actual work of dying—truly a carry up the mountain. Yet so often today, despite intending to do the best we can, we face a medical-care system that seems to work at odds with our parents’ stated desires and wishes to die at home, to let go when the time comes, “to avoid the suffering I have seen my friends go through.”

As a geriatrician I know that the canary in the coal mine of our failing health care system is the plight of the old and frail and their families. The vast machinery of modern medicine, which can be heroically invoked to save a premature baby, when visited upon an equally vulnerable and failing great-grandmother may not save her life so much as torturously and inhumanely complicate her dying.

In an opinion piece titled “It’s Time to March,” published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (May 2006), Drs. Knight Steel and T. Franklin Williams, two of the specialty’s wise elders, urge that, since reform within the larger medical profession has failed, specialists in aging should take to the streets with the public in protest. Our system of “fast medicine” is running a lockstep, breakneck course and no one in or out of health care seems to know how to put on the brakes. To maximize efficiency, doctors and nurses are always over-scheduled. Taking time for listening and understanding—much less time for interactions with families— is not paid for by Medicare and hence not usually undertaken in today’s acute- care medical environment. Patients are briskly shunted off for various kinds of expensive but Medicare-covered tests and procedures or quickly put on medications based on rapidly made decisions and standardized protocols developed mostly for the middle-aged.

American medicine is best at managing acute crises and supplying specialized elective procedures such as joint replacements, organ transplants, eye surgeries, cosmetic changes—all of them modern technological wonders. As for the chronic problems of aging and slow-moving diseases, our system has not done so well.

Some elderly patients are fruitlessly subjected to what some critics now call “death by intensive care.” Patients are sedated (thus unable to communicate) and subjected to impersonal medical protocols in strange, disorienting surroundings or stranded in limbo on life- support machines while their families hover in waiting rooms, uncertain how to help.

Much more commonly, elders suffer the accumulating burdens of illness and exhausting medical regimens that deplete all their available energy and time, leaving nothing left for living beyond a “medicalized” life.

Let’s for a minute consider an alternative I call slow medicine. The virtues of slowness, a rebalancing of the unbridled uses of the technologies of speed and efficiency, have been touted in many other areas—slow travel, slow cities, slow design. More than 20 years ago in Rome the Slow Food movement asserted an alternative to the standardized, industrialized, impersonal, high-tech tide of fast food sweeping across the world—local ingredients, pot simmering on the back burner, family and friends sitting at the table.

Slow medicine, a philosophy and approach that most elders and caregivers intuitively grasp, offers a parallel menu:

• Local ingredients—personal knowledge of elders, their circumstances, family and friends;

• Slow simmering—thinking, reflection and careful decision-making about complex and life-changing choices around medical care and locations for living;

• Conversing around a real (or virtual) table—sharing with family, friends, medical and other care advisors in a more reciprocal and coordinated way.

Dartmouth Medical School researchers at the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Utilization (www. dartmouthatlas.org) are showing that more care may not be better (see DAM cover story “The Overtreated American,” Nov/Dec 2003). Indeed, too much medical intervention may lead to a range of poor outcomes for elders. Poorly understood and inadequately considered medical decisions can produce a variety of unwanted outcomes, from the many dangers elders face during hospitalizations, through procedures that leave no energy for rehabilitation, to deaths that are anything but peaceful.

Slow medicine—deeply listening to the patient (for what is said and often unsaid), understanding the patient’s unique context and values, customizing care for the individual’s health history and temperament, and allowing enough time for processing decisions—is just what is called for. American high-tech fast medicine needs to be rebalanced with the ever-present need for committed human caring. Slow medicine offers just that. It is not a plan for getting ready to die, it is a plan for living well through the many years of late life.

DENNIS MCCULLOUGH, a professor at Dartmouth Medical School, was the founding medical director at Kendal at Hanover and is the author of My Mother, Your Mother (HarperCollins, 2008). His related Web site is www.mymotheryourmother.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA World of Difference

May | June 2009 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’04 -

Feature

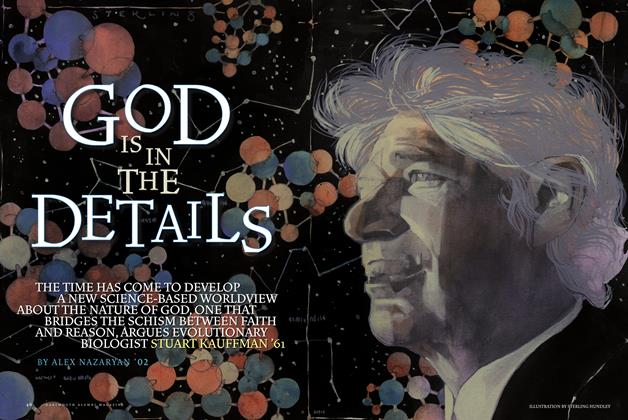

FeatureGod Is in the Details

May | June 2009 By ALEX NAZARYAN ’02 -

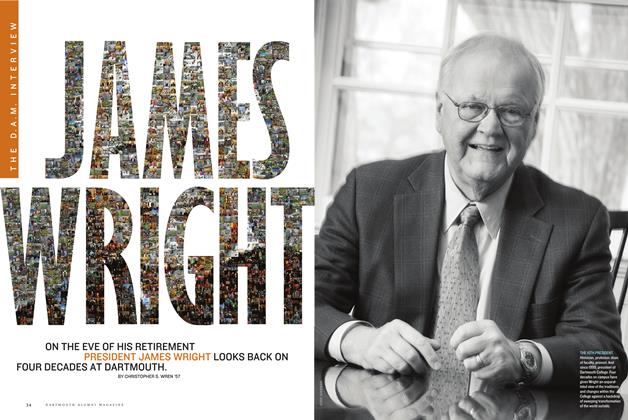

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWJames Wright

May | June 2009 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

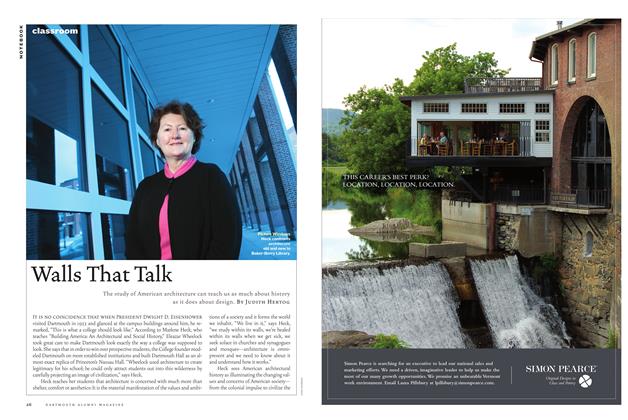

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWalls That Talk

May | June 2009 By Judith Hertog -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

SPORTS

SPORTSIn a League of His Own

May | June 2009 By Brad Parks ’96

FACULTY OPINION

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMillennial Mindset

May/June 2007 By Aine Donovan -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONEggheads vs. Meatheads?

Nov/Dec 2005 By DAVID KANG AND ALLAN STAM -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONA Sorry State of Affairs

Jan/Feb 2008 By Jennifer Lind -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAcross the Divide

July/August 2006 By Lucas Swaine -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Cost of Winning

Mar/Apr 2003 By Professor Ray Hall -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionDouble Trouble?

May/June 2001 By Ronald M. Green