Learning By Doing

Making the grade takes on new meaning for students training to become teachers.

May/June 2004 Julie Sloane ’99Making the grade takes on new meaning for students training to become teachers.

May/June 2004 Julie Sloane ’99Making the grade takes on new meaning for students training to become teachers. BY

TODAY'S LESSON: PRESSURE. "Pressure equals force divided by area," says Chad Butt '04. With the push of a button, PowerPoint slides the equation onto the screen. 'At sea level, atmospheric pressure is 14.7 pounds per square inch." He walks around his eighth-grade classroom, stopping in front of a lanky young man. "Air from the top of the atmosphere down onto Adams head is exerting pressure on him from all directions," Butt says to the class. "Is he going to die?"

Adams potential death-by-atmos-phere sends the class into fits of laughter and whispering. "Noooooo!" they giggle.

"No, he's not. But thank you for being concerned," Butt says dryly.

Here at Frances C. Richmond Middle School, adjacent to Hanover High, Butt is in charge of teaching earth science to 19 students who aren't hormonally inclined to sit still. Talk about pressure.

This year Butt became one of 12 Dartmouth students certified by New Hampshire to teach public school through the College's Teacher Education Program, of- fered by the education department. Although the program has produced 427 certified teachers since 1977, few Dartmouth students realize it exists. Every fall secondary teachers such as Butt simulta-neously take Education 46,47 and 48 with instructor Jay Davis '90. They show up five weeks before the start of fall term to begin an intense curriculum: full-time student teaching at an area public school (which includes daily lesson planning and homework grading); two weekly seminars with Davis; about a hundred pages of required reading every week; and assignments ranging from daily journals to shadowing an inner city high school student. (There is also a parallel sequence-Education 42,43 and 44—for elementary teachers taught by Janet Zullo.)

For 15 weeks the student teachers' lives are radically changed. While many of their peers swear off 9 a.m. classes as "too early," the teachers are up by 6:30 a.m. and in bed by 11 p.m. Davis formally offers wake-up calls to any of his students. "They need to learn that lateness is not an option," he says. "They represent Dartmouth and they have kids counting on them." And forget about the time-honored tradition of all-nighters. "That would have disastrous results in the classroom the next day," says Zac Leghorn '04. There are also small, symbolic differences. This term teaches the students where to buy a cup of coffee in Hanover before 7 a.m. (Answer: Foodstop or Lou's.) They learn to pack tomatoes separately to prevent a soggy sandwich. They find that fitting in something as simple as a daily jog takes precise time management.

In the face of careers in fields such as law and business that bring more cachet and income, Davis calls becoming a teacher at Dartmouth "an act of social defiance," a phrase he borrows from education department chair Andrew Garrod. "Parents say, 'Go to Dartmouth to be a teacher? I'll send you to fill-in-the-blank technical college,' " says Davis. "But I would argue that these are people we most want teaching our children."

Adored by his Dartmouth students, who describe him strictly in superlatives such as "phenomenal" and "amazing," Davis walks and talks in one speed: fast. He is also known for making puns and whistling classical music through his teeth. Before joining the Dartmouth faculty in 2001, Davis was the assistant director of Dartmouth's Composition Center, a coach for Dartmouth's Nordic ski team, and both a private and public school teacher for eight years. He also teaches Education 45: "Principles of Teaching and Learning in the Secondary Classroom" in the spring. That 15-student class is both a prerequisite for the fall student teaching and a course taken by seniors looking to teach at private schools or with Teach For America.

Davis remains a part-time English teacher at Richmond Middle School and has no intention of giving it up. He has an hour break between teaching 13-year- olds and 22-year-olds. There's often an eerie connection with what Davis experi- ences in one classroom and teaches in an- other. On the day he was to teach a lesson on confidentiality at Dartmouth, Davis got a note from one of his seventh- graders saying a boy had asked her out and she had said no. "I think he's going to hurt himself. Please don't tell anybody," said the note. Davis read the note to his Dartmouth students with the name omitted. 'An hour ago I met with this student," he told them. "Pair up and in 10 minutes decide what you would do in my position." (Davis' solution was to ask the girl if she understood why he couldn't keep her secret. She did, and they contacted the school counselor right away. Everything turned out fine.)

The student teachers also find their worlds overlapping. In a small community such as the Upper Valley, they can't avoid running into students and parents at the grocery store or on the Green. Last year one student teacher was leaving his fraternity house as one of his high school students was showing up, interested in buying drugs. He immediately turned her away and contacted Davis. Worried about both the student and his own reputation, the student teacher decided he should inform the school principal.

It isn't all ethical dilemmas. Teacher Lydia Wheatley'03 is also co-captain of the women's hockey team. At the home games this winter, her seventh-grade geography students lined the ramp, yelling "Go Miss Wheatley!" (Her teammates also started cheering for "Miss Wheatley" too.)

At the very beginning of the term Davis teaches a seminar called "What To Do When the Mr./Ms. Is You," helping students understand the transformation from fleece-wearing college kid to adult authority figure. Katherine Anderson '03 was terrified when she first introduced herself as Ms. Anderson to the sixth-graders at Lyme Elementary School. "I looked much more like the students than the teachers in my school," says Anderson, who stayed an extra fall term to get her teaching certification. The students considered me a teacher and an authority figure way before I could."

Davis designs each two-hour seminar for maximum content in minimum time. Class begins with a "wraparound," where students share one story about their teach- ing. "I want to keep a connection with what's happening in their classrooms, but keep a lid on it so it's not two hours of what's going on in their school," explains Davis. Another weekly ritual is "chalk talk," where students use the blackboard to free associate on subjects such as "com- munication with parents." Davis also uses seminar time to pull out the practical and usable lessons from the assigned reading. Students frequently break up into pairs to discuss and then share with the group what stood out for them.

In one such discussion, Leghorn, who taught French at Mascoma Valley Regional High School, brought up the challenges of motivating at-risk students to aspire to more than a job at Wal-Mart, particularly when some of their parents work there. "You want to connect with them, but not to put down what their families do," he says. Teachers, they all agree, walk a fine line in giving advice from their own perspectives while realizing there may be unknown circumstances in a students family life. "If a student seems down about her father, I can't say, 'Oh, I'm sure your dad loves you,'" says one student. "It's possible her father is abusing her." Another agrees. "Why don't they have their homework?" he asks. "It could be because they worked until 10 p.m. last night."

With the school year ending and the inevitable retiring and reshuffling of teachers, Davis' newly certified students are heading out to look for jobs. Butt is in- terviewing for a position at Richmond Middle School and considering a job with AmeriCorps. Wheatley wants to teach in her native Michigan, Leghorn and Ander- son in northern New England. Davis en- courages them to sign on with schools that will assign them mentor teachers. "My overarching passion is preparing young teachers to give what students need without burning out," says Davis. "I hope the class served as a bit of a laboratory where they could learn to keep support and balance in their lives."

No Child Left Behind Chad Butt '04works with some of his eighth-gradersat a Hanover middle school.

JULIE SLOANE is a writer at Fortune Small Business magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Great Disconnect

May | June 2004 By ED GRAY ’67, TU’71 -

Feature

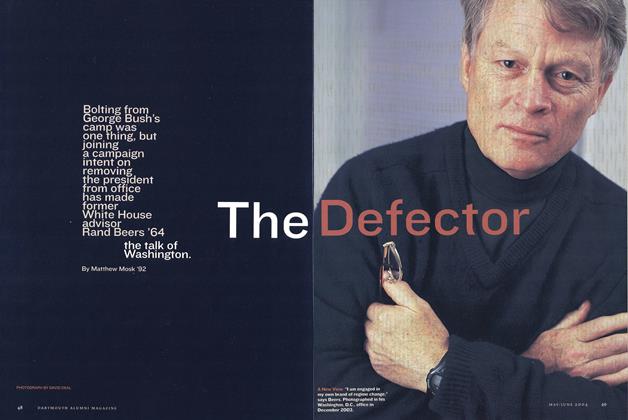

FeatureThe Defector

May | June 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May | June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

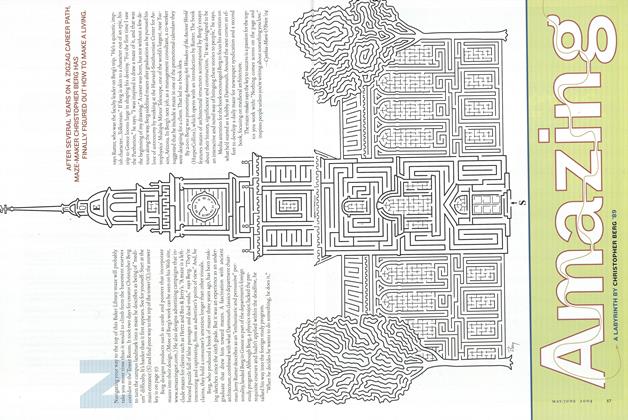

FeatureAmazing

May | June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Sports

SportsStraight Shooter

May | June 2004 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu’71

Julie Sloane ’99

-

Article

ArticleHealing Outside the Hospital

MAY 2000 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Feature

FeatureUnderstanding Failure

Jul/Aug 2004 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Human Condition

Sept/Oct 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Cover Story

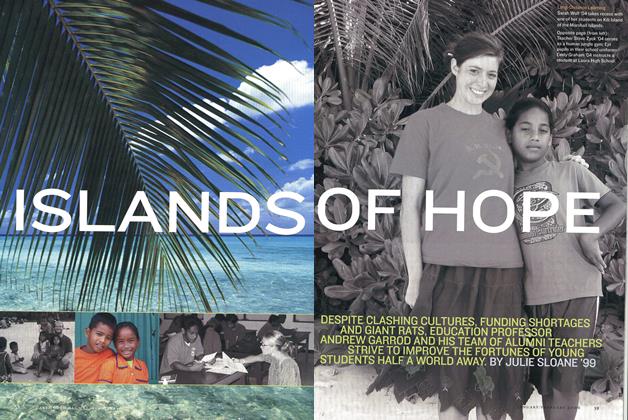

Cover StoryIslands of Hope

Jan/Feb 2006 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCorps Values

Jan/Feb 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Feature

FeatureOh Behave!

July/August 2012 By Julie Sloane ’99

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMGOOD VIBRATIONS

JULY | AUGUST 2025 By EMMA JOYCE -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMHe Says, She Says

Sept/Oct 2008 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMBorder Patrol

May/June 2005 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMFrom the Page to the Stage

Mar/Apr 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

Nov/Dec 2002 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWall Papers

July | August 2014 By LISA FURLONG