A Well-Traveled Story

Student tastes in fiction may be ever-changing, but one stalwart holds true for every generation: On the Road by Jack Kerouac.

July/Aug 2009 Ernest HebertStudent tastes in fiction may be ever-changing, but one stalwart holds true for every generation: On the Road by Jack Kerouac.

July/Aug 2009 Ernest HebertStudent tastes in fiction may be ever-changing, but one stalwart holds true for every generation: On the Road by Jack Kerouac.

HOT WRITERS AND HOT BOOKS come and go on campus, but in the 22 years I’ve taught fiction writing at Dartmouth only one book pops up every year, in fact almost every term, without me ever mentioning it.

it’s that iconic Beat Generation novel On the Road by Jack Kerouac. There are good reasons why this book has staying power with American young people. As long as teenagers have access to cars, On the Road will remain a must read.

Basically the characters in On the Road just drive around and hang out. The book has a bare-bones beginning and no end. On the Road is all middle, a continuous stream. In America from the late 1940s on-ward, “stream” translates into road. On the Road is life as a road trip. This is not a book for people who have settled down to jobs, families and responsibilities.

Part of the lure of Kerouac and On the Road is the story behind his writing of the first draft—on a roll of tracing paper in three weeks. The manuscript is one 120-foot-long page. what’s left out of the story is that it took Kerouac six years of rewriting to make it acceptable to his publisher.

On the Road is a book for young people, especially young men. What separates it from other coming-of-age novels and what gives it enduring appeal is the intensity of the prose, its familiarity to youth and the way it uses the road as a metaphor to signify freedom and connectivity to the landscape and to America itself. In a car moving at high speed the road is exhila-rating and liberating. The occupants are protected from scrutiny by the out-side world, but at the same time they’re sealed off. the result is that there’s a loneliness about the road. One of Kerouac’s favorite words—no doubt derived from his Franco-American Catholic upbringing in Lowell, Massachusetts—is “sorrow.” for kerouac and for his readers there’s sorrow in recognizing the impossibility of achieving both the dream to be free and the dream to belong.

Their elders coach young people to seek success—to be winners—and to calm down, but what young people really want is excitement, meaning and validation of their passions. In the Declaration of Independence Thomas Jefferson talked about the “pursuit of happiness.” i’m sure he never dreamed that youth in future centuries would take the “pursuit” part so seriously and in a conveyance that traveled at 90 miles an hour on a two-lane road.

Truman Capote whined that Kerouac’s prose was not writing—it was merely typing. I think many of my colleagues would agree. Academics are suspicious of kerouac. he’s not high on the required reading list in 20th century American literature. And yet scores of books have been written about Kerouac.

I asked Ann Charters, who wrote the first biography of Kerouac, why he was and remains so popular with biographers. her answer: “Because he kept good notes.”

Most of us writers, myself included, are slobs and do a lousy job of creating a paper trail. By contrast, Kerouac made copies of the many letters he wrote. He put all his thoughts on note cards and filed them by date. He was a fastidious record-keeper of his adventures and he listed his faults along with his virtues.

Capote was wrong about Kerouac. He did write a lot of blather, a result of a theory that he called spontaneous prose. Kerouac spent a lifetime pursuing and capturing those moments when a great idea hits you, say, when you’re in the shower. When he succeeded, however, he produced some startling and beautiful prose, the verbal equivalents of jazz riffs. in On the Road he wrote, “the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes ‘Awww!’”

What Kerouac was after is a feeling, that mixture of excitement and confusion that marks American young people as they try simultaneously to shape an individual identity and to belong to a group of like-minded people.

Joe Blessing ’12, one of my first-year seminar students, summarized kerouac’s appeal in an essay: “while reading On the Road will remain a rite of passage for rebellious [youth], it is this quality of encapsulating American internal conflicts which gives kerouac’s work such power and pathos and for which American culture is indebted to him.”

I think Blessing is right in his critique. Most young people struggle with internal conflicts. These tensions are played out in On the Road. it’s a book that stimulates young people, especially young men, to travel, to depend on one another, to examine their beliefs and passions and to write it all down as honestly as possible.

Scrolling Text Kerouac’s original draft sold at auction for more than $2 million in 2001.

ERNEST HEBERT has published eight novels. In 2007 he published an essay collection, New Hampshire Patterns (UPNE).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

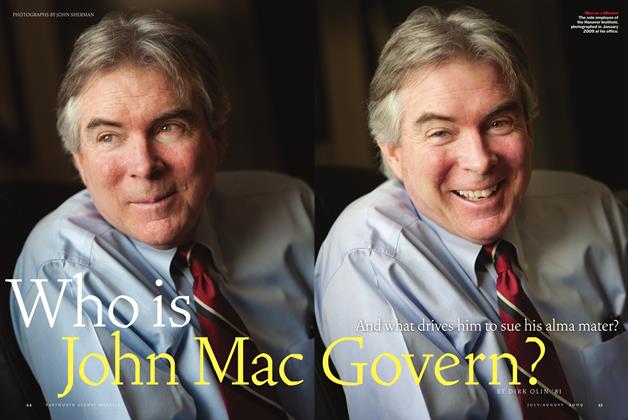

FeatureWho is John MacGovern?

July | August 2009 By Dirk Olin ’81 -

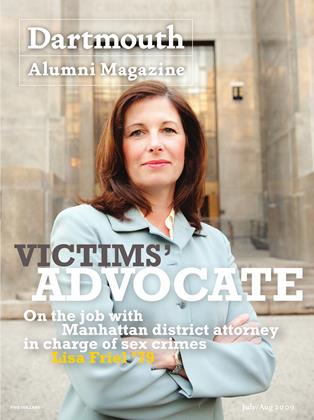

Cover Story

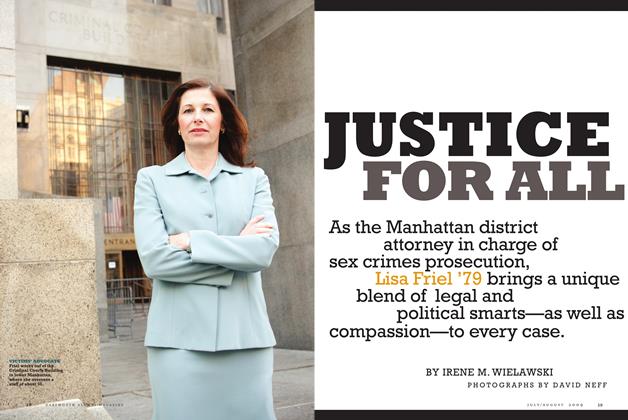

Cover StoryJustice for All

July | August 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

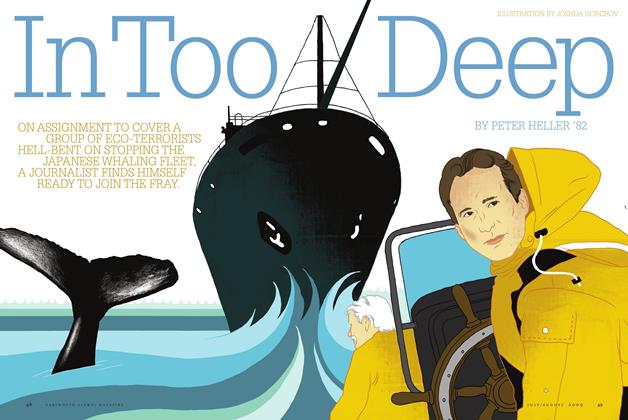

FeatureIn Too Deep

July | August 2009 By PETER HELLER ’82 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Skipper

July | August 2009 By Sarah Tuff -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

FILM

FILMLife’s Big Questions

July | August 2009 By Lauren Zeranski ’02

FACULTY OPINION

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONThe Perils of Innovation

Nov/Dec 2010 By Chris Trimble and Vijay Govindarajan -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONEggheads vs. Meatheads?

Nov/Dec 2005 By DAVID KANG AND ALLAN STAM -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionTrade, Jobs and Politics

Jul/Aug 2004 By Douglas A. Irwin -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAcross the Divide

July/August 2006 By Lucas Swaine -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Cost of Winning

Mar/Apr 2003 By Professor Ray Hall -

FACULTY OPINION

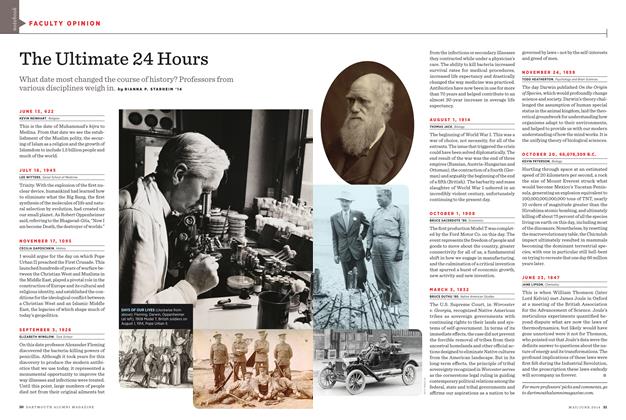

FACULTY OPINIONThe Ultimate 24 Hours

MAY | JUNE 2014 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14