Stories in Stone

A former student reflects on his independent study of the rural life with the late professor Noel “Ned” Perrin.

May/June 2005 Andy Rowles ’65A former student reflects on his independent study of the rural life with the late professor Noel “Ned” Perrin.

May/June 2005 Andy Rowles ’65A former student reflects on his independent study of the rural life with the late professor Noel "Ned" Perrin.

LAST NOVEMBER NED PERRIN died before we finished repairing the stone walls in our neighborhood. It all started 40 some years ago, when I was 18 and Professor Perrin was my freshman advisor at Dartmouth. He was 34, married, with a newborn daughter, and living somewhere across the river. He brought a few of us freshman know-nothings out to his old farmhouse in Rice's Mills, Thetford, for a meal. To me, a product of the New York City and Philadelphia suburbs, Hanover seemed remote. Thetford Center seemed completely off the map.

That fall day we walked half a mile up a nearby dirt road to some abandoned farmland that Ned owned. It was made up of side-hill, brushy fields with fallen stone walls that hinted at the farming that took place there before the woods filled in. Eight years later Ned sold me a piece of that side-hill. We walked the edges, decided it was 10 acres "more or less," and worth about $175 an acre.

Done.

He wanted me to have it, and I'm still living there today. At the time I didn't guess that he had a hidden agenda.

My first year at Dartmouth was mostly a disaster. The only course I attended with anything like enthusiasm was a freshman English course on Utopian literature. I liked reading about better worlds more than I liked being a student in this one. The instructor? Well, you know who.

By spring I was ready to quit school, so I went to Ned, my advisor, to maybe get some encouragement to stick with it.

"Why don't you drop out?" was his response. It was unconventional advice for the time, and exactly right. I needed to do something independent to get beyond feeling bored and restless at Dartmouth. It turned out that two years in the Army was a fine education, tuition-free. I lived in exotic places such as Georgia and Texas among other draftees, white and black, city and country. It was concrete; it was not a Utopian idea. There were lessons on race and class unavailable at Dartmouth. Then came the rest of college, the Peace Corps in Micronesia, medical school and eventually a move to Thetford in 1978 with my then wife, Barbara, and our 4-year-old son, Zach.

Afew years later Ned revealed his hidden agenda: "Why don't we trade working on our stone walls?" Ned loved stone walls. Not those perfect walls made of quarried stone delivered on pallets but the ones built from stones delivered, one at a time, to the surface of pastures. He loved gathering stones with his truck, preferably from the top of Bill Hill, elevation 807 feet and conveniently located on his farm. He admired the good ones and the little "chinkers" that lock the rest together. For the next 20 years, whenever we could, we would spend a few hours on the walls. We started around 8. He might arrive at my house in one of his various electric cars, so quietly I wouldn't hear him. Out came the work gloves and pry bar. (We always brought our own pry bars.) We would pick up wherever we left off last month or last year. The home wall owner would make the difficult calls on rock placements, but mostly we just dug em out of the ground and piled them up.

This mentally easy work left us free to take the conversations in many direc- tions. There were marriages to talk about, maple-sugaring techniques, weather ob- servations, Utopias even. We had our fa- vorites. I liked to remind Ned of the time he showed off his chainsaw skills to a lady from Connecticut. He managed to drop a tree onto her arm and she ended up in a cast. To get her home he drove her in her car to the southbound interstate ramp, where she took over, one-armed. A straight shot to Connecticut, he said. Barbara and I gave him a ride home. I don't believe the woman came north much after that. We ended each morning with coffee and something sweet. We both liked local sweets the best and that led to more talk of farming, land conservation, apples and so on. Many conversations went into building those stone walls. Many baked goods, too.

Ned didn't just wait for me. He worked on his own walls all the time. To him a morning spent moving stones around nicely complemented afternoon office hours down in Hanover. He liked to call my part-time doctoring and part-time homesteading a "Dagwood sandwich life," but he cultivated his own Dagwood days. It wasn't just a pretty wall he enjoyed, his walls needed to contain real cows—cows neighbor Floyd Dexter might have bought at Gray's auction and pastured at Ned's. He cared about the uses of land and its products, such as hay, milk, beef, eggs and syrup.

But Ned was a writer and a professor, so he used the pen to laugh at his own amateur farming, and he found real farmers such as Floyd to show him how to go about learning more. He also encouraged people such as me to learn with him and deepen our appreciation of the farms and people of rural Vermont. Ned was able to see the stories in stone walls and add his own walls, his own stories.

We were both students of a 20-year pasture improvement course, hands-on, with no instructor. My reward was the pleasure of Neds company and something else that Ned always understood. He put it like this in "Baling the Village," a story in his book, Last Person Rural: "For a little while we were part of the rhythm of the season, the village, and the land."

ANDY ROWLES, a retired family physician,lives down the road from Perrin's farm in Thetford and keeps busy outside year-round.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

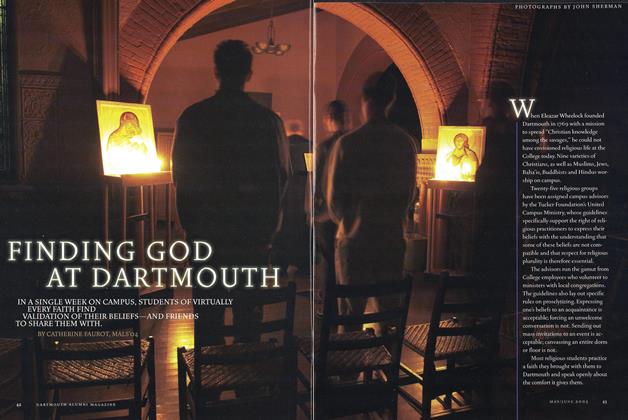

Cover StoryFinding God at Dartmouth

May | June 2005 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’04 -

Feature

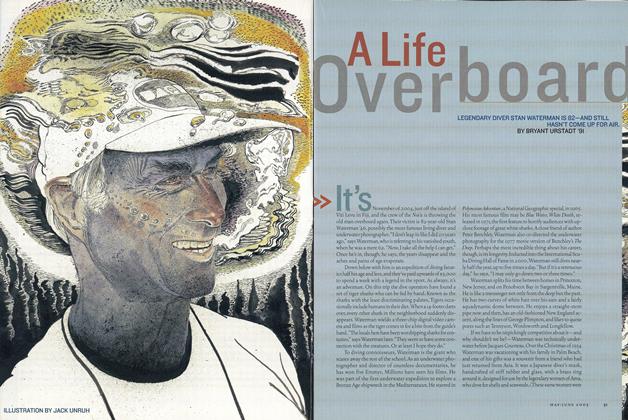

FeatureA Life Overboard

May | June 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

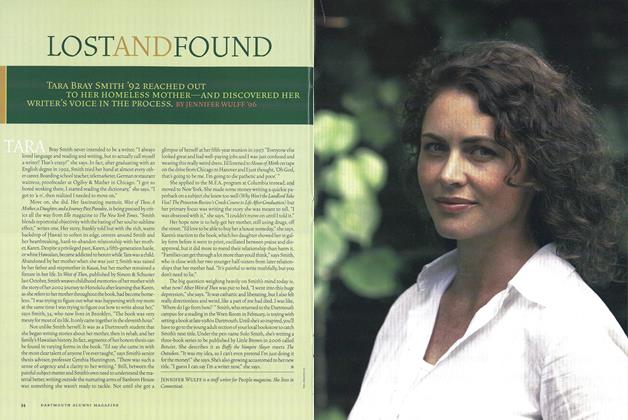

FeatureLost and Found

May | June 2005 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2005 By Olivia Britt '00 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONShiny Bubble

May | June 2005 By JOHN H. VOGEL JR.

TRIBUTE

-

Tribute

TributeThe “Prone Ranger”

May/June 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEHER LESSONS ECHO STILL

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 By DAVID DOWNIE '88 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEA Life Well Lived

Jan/Feb 2011 By Deborah Schupack ’84 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTERemembering Earl Jette

JULY | AUGUST 2025 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

TRIBUTE

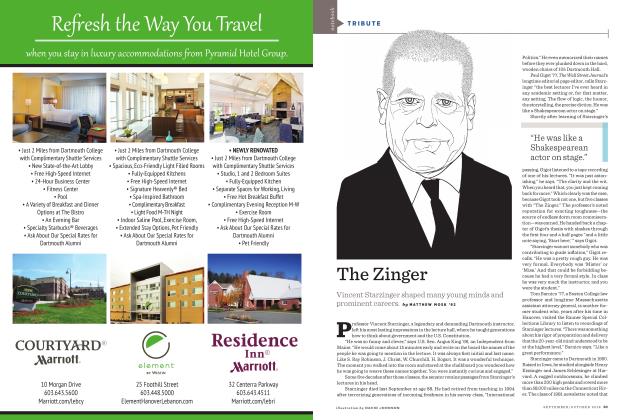

TRIBUTEThe Zinger

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTESage on Stage

Mar/Apr 2008 By Mike O’Connell ’65