Luck of the Draw

Friends and fellow players remember card master Chip Reese ’73, a poker legend right out of an Elmore Leonard novel.

Nov/Dec 2008 Bryant Urstadt ’91Friends and fellow players remember card master Chip Reese ’73, a poker legend right out of an Elmore Leonard novel.

Nov/Dec 2008 Bryant Urstadt ’91Friends and fellow players remember card master Chip Reese '73, a poker legend right out of an Elmore Leonard novel.

The Best Poker Player Ever Died of a heart attack in his sleep at his home in Las Vegas last December. His name was Chip Reese. He was 56, a BetaTheta Pi and a member of the class of 1973.

"He was arguably the best poker player that ever lived," says Doyle "Texas Dolly" Brunson, who would certainly vie for that title himself if he weren't giving it away to Reese. "He was certainly the best player I ever sat down with," Brunson adds.

Reese grew up in Centerville, Ohio. As with so many great minds, he achieved suc- cess that appears to have been rooted in an early illness. As his sister Nancy Reese Clark tells it, he spent his entire first-grade year bedridden with rheumatic fever, following the advice of doctors, who believed then that even so much as walking around could endanger his heart. His mother helped pass the time by teaching him card and board games of every kind. His great grandmother taught him poker, and they played for pennies. Reese would later call himself "a product of that year." Though he was no cheater, he did admit later that he could see his great-grandmother's cards reflected in her dark glasses.

The following year he started playing poker with a group of fifth-graders and won all their baseball cards. At Centerville High School he won a state championship as part of the debate team and played center on the football team, where he was also a co-captain.

He arrived at Dartmouth a fully formed card-playing talent. He spent so much time winning at cards in the Big Daddy Lipinski Poker Room at the Beta house that Rick Pummill '75 made up a special plaque re-naming it the David E. Reese Memorial Poker Room during Reese's senior year. Pledges were later required to memorize the 15 names on it, most of whom lost money to Reese.

Reese was always in that room, playing rich students and professors, remembers Marc Josephson '71. By the end of his freshman year, classmates recall, he had earned $4,000, roughly the cost of tuition at Dartmouth at the time. Among his frequent victims were two professors of economics, Jim Dobson and Ben Branch. Dobson would later work for the Federal Reserve, but he was no match for the teenaged Reese.

The player taught his brothers a lot about poker. The most valuable thing Josephson says he learned was to avoid the game entirely. "I figured that out very early," he says. "Once I played poker with Chip I learned never to play again."

DanaMartino '74, a fraternity brother and lifelong friend, joined the football squad with Reese their freshman year. Reese didn't last long.

"He took a look at the travel schedules for the football and the debate teams," remembers Martino. "The football team went to Boston and Ithaca. The debate team was going to Hawaii, so he tried out for the debate team."

Knowing how disappointed his parents would be, Reese pretended in letters home that he was playing football, and maintained the ruse through a visit from his parents, asking freshman coach Jack Curtis if he could borrow a uniform and sit on the sidelines for a B-team game. Jack Manning '72, Reese's senior-year roommate, remembers that it worked and his parents were none the wiser.

Reese seemed to care little about the money he won and lost, possibly one of the prerequisites for surviving as a big bettor. At Dartmouth he quit doing laundry, buying new clothes when the old ones got dirty; Martino remembers taking a load out to the dumpster. Once Reese went to the Tally House in White River Junction and ordered everything on the menu, according to Pummill. Later in life he wouldn't bother with dishes either, ordering take-out complete with place settings and silverware. When brothers came to visit him in Vegas he would give them handfuls of hundreddollar bills and tell them to go out and have fun.

Reese rarely had any cash flow problems. In 1984 Pummill had just had his first child, and Reese stopped by on his way to their multi-class 10th reunion in Hanover. Pummill admitted he didn't think he could afford to go to the reunion, with the new baby and all. Reese brought out a briefcase, which he opened to display $5,000 in wrapped, $100 bills.

"Is that enough?" asked Reese.

"I guess so," said Pummill.

"Then you gotta go!" said Reese.

They were on a plane the next morning.

After Dartmouth Reese stopped in Las Vegas, supposedly en route to Stanford Law School.

When A. Alvarez wrote about poker in Vegas for a four-part series in The NewYorker in 1980, he described Reese's ascent: "He had $400 in his pocket when he sat down in a $20-limit seven-card stud game; at the end of the first day he had won $800; the next day he won $1,000; within a fortnight he was $25,000 ahead." At the end of the summer Reese entered a $500 buy-in tournament at the Sahara, which he won, with a $40,000 take, bringing his total haul to more than $60,000.

"He pretty much never left," says his sister. He hired a friend from Vegas to fly home and bring down his stuff and his car.

"He was never going to end up anywhere but in Las Vegas," says Martino. "He knew from the beginning this was all he ever really wanted to do."

By September he had amassed $1000,000, and law school was shoved aside. Over the ensuing months he started playing the top players in Las Vegas, including Doyle Branson, who would become a lifelong friend. Reese quickly became well enough known to merit a nickname: "The Ivy Leaguer."

"I first played with him when he was 22," says Brunson, who was 18 years older. "It was obvious right away that he was a real talent. He did naturally what it took me years to learn." As examples Brunson points to Reese's understanding of the chemistry at a table, and how to "cool off" a player "chasing" him.

Brunson asked Reese to contrib- ute the chapter on seven-card stud to Brunson's bestselling poker bible, SuperSystem. They spoke almost every day and entered into a number of business ventures together, including funding searches for the Titanic—"We almost found it," says Brunson—and for Noah's Ark. These (mis)adventures never produced anything other than a desire to get back to the cards.

In time Reese married Noralene Boyer and they had two children, now teenagers. (The couple divorced shortly before his death.) Known as a dedicated father, Reese reportedly once walked away from an $8000,000 loss to go to his sons T-ball game.

For years Reese managed the card room at the Dunes, which later would become the Bellagio. As manager he hired dealers, chose the games being played, attracted the big players and made sure they stayed happy. Writer Alvarez, finding him about that time, described him thus: "His hair is blond and unruly, his plumpness is turning to fat and his round face appears jolly until you see his eyes. He dresses in extravagantly colored velvet track suits.' (His sister points out that the garish colors of his clothes were not so much a stylistic choice as a byproduct of being colorblind.) In later years, as judged by numerous You Tube videos of Reese competing in various games, he seemed to have left the fat, the track suits and at least some of the hair behind. And maybe even the hard eyes.

Reese's specialty? Unlimited cash games, where a player would sit down with $100,000 or $200,000 in chips and bet in $4,000 and $100,000 increments. Reese typically joined such a table with $500,000 on hand. Pots frequently grew into the millions. For years Reese played in "The Big Game" in Bobbys Room at the Bellagio, generally considered the biggest table in town. It's a table where professionals and amateurs with big bank rolls gather.

"There is a mystique about 'The Big Game,' " says Steven Lipscomb '84, who got to know Reese while managing the television production of the World Poker Tour, which Lipscomb founded. "And a big part of that mystique was that Reese and Brunson were at that table."

Lipscomb feels that much of Reese's strength as a player derived from an innate and practiced understanding of human psychology. "After playing with you for 10 or 15 minutes he had a pretty good idea of what you had in your hand," says Lipscomb. "He picked up on everything, the subtle 'tells,' such as how you held your.cards, how you moved your chips to make a bet. It was sheer, raw intuition, and his instincts were impeccable."

Many big shots, or "fish" as professional poker players call them, would show up just to play Reese, wanting a game with the best. Former Dartmouth roommate Manning remembers sitting by Reese as he played corporate raider Carl Icahn, and watching another game with Bill Gates, whom Reese told would never win in poker if he didn't take any risks. Reese also played many games with Larry Flynt, the publisher of Hustler magazine and a poker fanatic.

Another well-heeled amateur was Gabe Kaplan, better known as "Mr. Kotter" from the 1970s sitcom WelcomeBack, Kotter. Reese would from time to time visit a spa in La Costa, California, with Martino and other friends, and Kaplan lived nearby. Kaplan played Reese frequently. And lost frequently. "He was one of Reese's regular 'pigeons,'" says Martino, using the insider's term for a player with more money than skill. Martino remembers being dispatched by Reese to pick up a brown paper bag full of cash from Kaplan at his home. "It was a sack full of $100," says Martino.

Reese did go broke more than once in Vegas in his first years, learning the ins and outs of the various forms of poker. When he felt he could make a steady living, he invited Martino down, as Martino wanted to try life as a player. Martino never made it as a professional, but in 2004 he gave up a 20-year career as a lawyer when Reese helped land him a job as a dealer at pokers headquarters, the Bellagio. Martino often dealt to Reese, though Reese always seemed to have bad luck when he did.

The gambler made plenty of money in his long career. He lived in a 13,000-square-foot house in Las Vegas, the most outstanding feature of which was his "office," and people talking about it always put that word in quotes. It had a desk on a raised dais and, more importantly 20 television sets, each tuned to a different sporting event. (Reese was also an avid and successful sports bettor.) He also owned homes in Santa Monica, California, and on Flathead Lake, Montana.

"Chip bought that last home after I got married," says Manning. "I had a party up at my place in Montana for a week and Chip came up. He hooked up with some gamblers from New York and pretty much played for a week. He won somewhere between $275,000 and $300,000 and bought a house on the lake with it."

The unlimited cash games, though more profitable, didn't get TV coverage. As poker blossomed into a televised sport with the World Series of Poker games, his kids urged him to join so they could see him on TV. So he did, and won the series' H.O.R.S.E. tournament in the summer of 2006. The H.O.R.S.E. tournament includes five rounds of five different styles of poker—hold em, Omaha, razz, seven-card stud, and eight or better hi-lo stud—and is considered the ultimate test of a player. Reese beat professional Andy Bloch in a final game that lasted seven hours and 286 hands. The grand prize was $1,716,000. His lifetime winnings at tournaments alone were more than $3,400,000.

Last March about 40 of his friends from Dartmouth gathered in Las Vegas to remember both Reese and his good friend and classmate Chuck Thomas '73, who died just months before. It was a weekend full of some of Reese's favorite activities, including ribs at the Sahara; a dinner at the South Point hotel, where guests got up and spoke about Reese; plenty of golf, which Reese enjoyed playing and betting on; and, of course, poker.

"I can't tell you how much enjoyment I got out of knowing Chip, hearing about him, visiting him. He was an exciting part of my life," says Manning, who attended the event. "I think we all felt that way."

Reese's strength as a player derived from an innate and practicedunderstanding of human psychology.

Bryant Urstadt is a contributing editor to DAM. He lives in New York City.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

COVER STORY

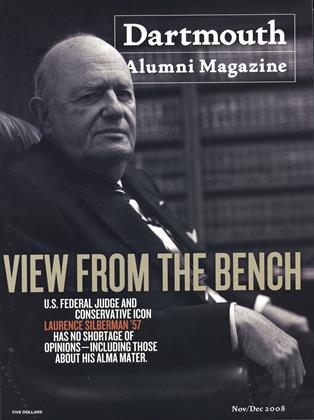

COVER STORYView From the Bench

November | December 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

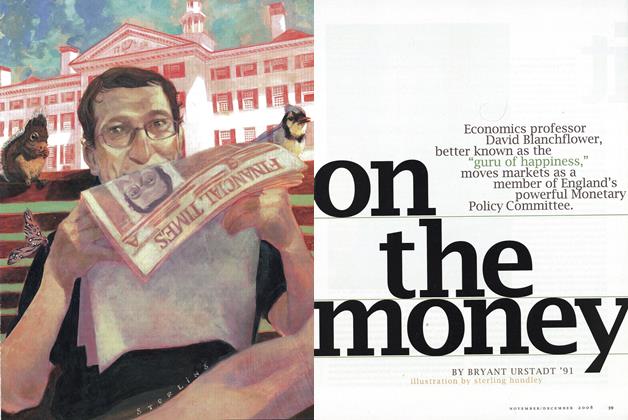

FeatureOn the Money

November | December 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

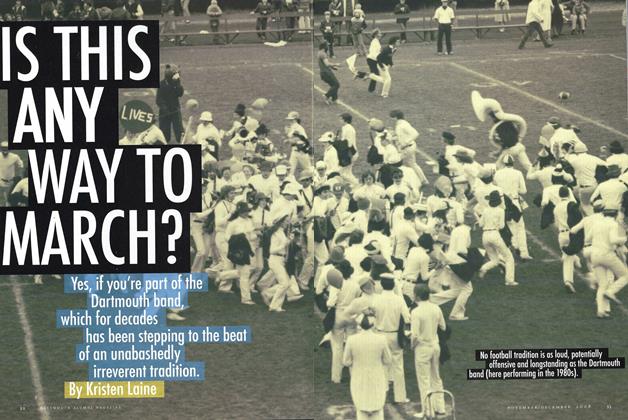

FeatureIs This Any Way To March?

November | December 2008 By Kristen Laine -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2008 By TIM FITZGERALD -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2008 By Bruce Beasley '61 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

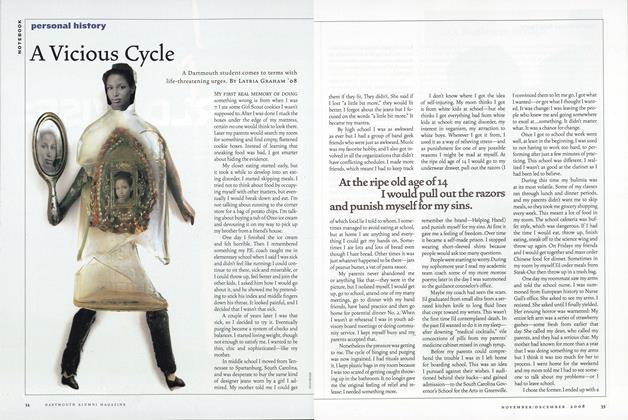

PERSONAL HISTORYA Vicious Cycle

November | December 2008 By Latria Graham ’08

Bryant Urstadt ’91

-

Feature

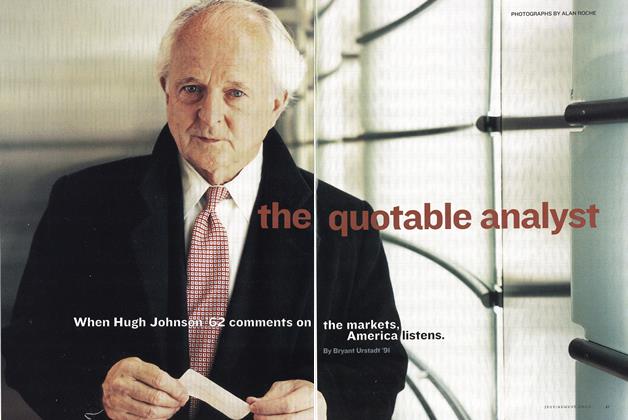

FeatureThe Quotable Analyst

July/Aug 2002 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

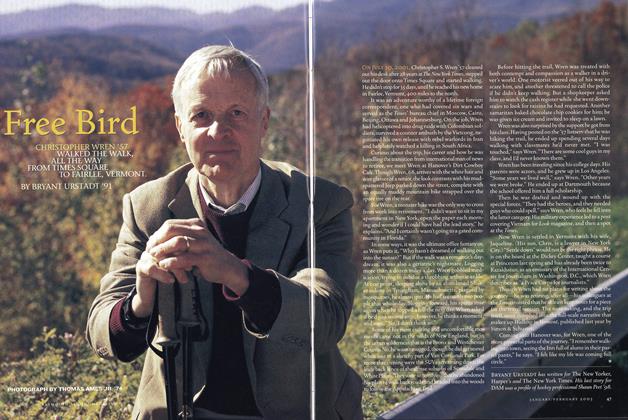

FeatureFree Bird

Jan/Feb 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryVoices Crying (and Laughing) in the Wilderness

Sept/Oct 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSShrimp, Sirloin, Sass

July/August 2006 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

FeatureCold Warrior

Jan/Feb 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

FACULTY

FACULTY“This Is Gonna Work”

Sept/Oct 2009 By Bryant Urstadt ’91

TRIBUTE

-

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEHer Lessons Echo Still

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 By DAVID DOWNIE '88 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEA Go-To Guy

Nov/Dec 2004 By David Shribman ’76 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTE“Why Blue?”

July/August 2011 By James D. Fernández ’83 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEChristian Existentialist

Nov/Dec 2007 By Jeffrey Hart ’51 -

TRIBUTE

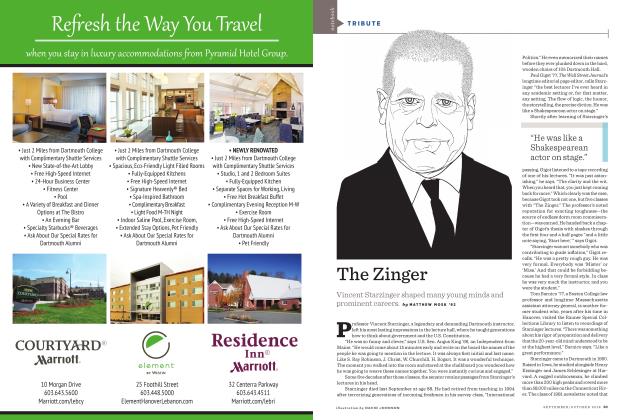

TRIBUTEThe Zinger

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

TRIBUTE

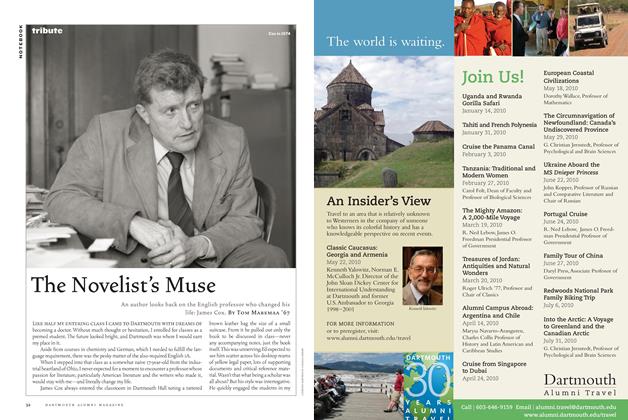

TRIBUTEThe Novelist’s Muse

Nov/Dec 2009 By Tom Maremaa ’67