A Go-To Guy

Remembering President Emeritus David McLaughlin ’54, Tu’55 (1932-2004).

Nov/Dec 2004 David Shribman ’76Remembering President Emeritus David McLaughlin ’54, Tu’55 (1932-2004).

Nov/Dec 2004 David Shribman ’76Remembering President Emeritus David McLaughlin '54, Tu'55 (1932-2004).

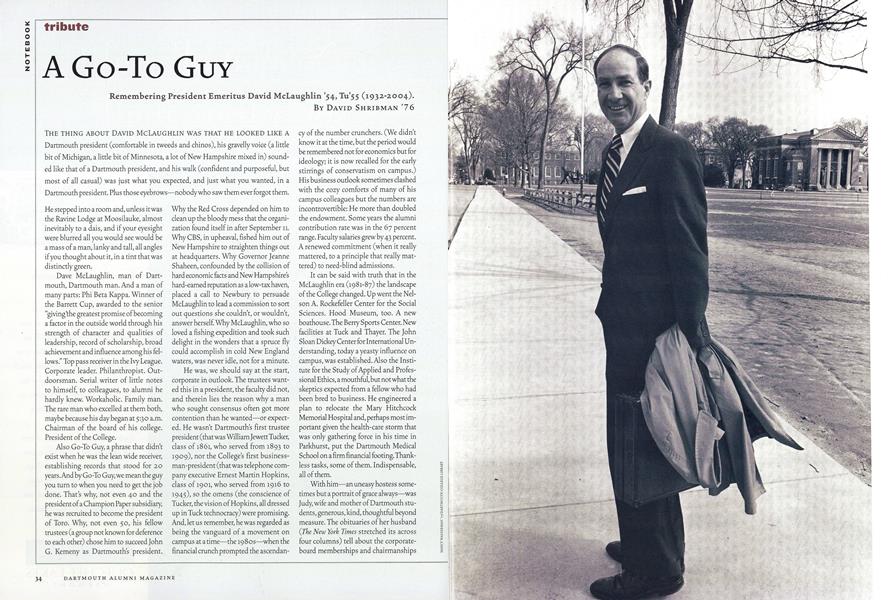

THE THING ABOUT DAVID MCLAUGHLIN WAS THAT HE LOOKED LIKE A Dartmouth president (comfortable in tweeds and chinos), his gravelly voice (a little bit of Michigan, a little bit of Minnesota, a lot of New Hampshire mixed in) sounded like that of a Dartmouth president, and his walk (confident and purposeful, but most of all casual) was just what you expected, and just what you wanted, in a Dartmouth president. Plus those eyebrows—nobody who saw them ever forgot them.

He stepped into a room and, unless it was the Ravine Lodge at Moosilauke, almost inevitably to a dais, and if your eyesight were blurred all you would see would be a mass of a man, lanky and tall, all angles if you thought about it, in a tint that was distinctly green.

Dave McLaughlin, man of Dartmouth, Dartmouth man. And a man of many parts: Phi Beta Kappa. Winner of the Barrett Cup, awarded to the senior "giving the greatest promise of becoming a factor in the outside world through his strength of character and qualities of leadership, record of scholarship, broad achievement and influence among his fellows." Top pass receiver in the Ivy League. Corporate leader. Philanthropist. Out- doorsman. Serial writer of little notes to himself, to colleagues, to alumni he hardly knew. Workaholic. Family man. The rare man who excelled at them both, maybe because his day began at 5:30 a.m. Chairman of the board of his college. President of the College.

Also Go-To Guy, a phrase that didn't exist when he was the lean wide receiver, establishing records that stood for 20 years. And by Go-To Guy, we mean the guy you turn to when you need to get the job done. That's why, not even 40 and the president of a Champion Paper subsidiary, he was recruited to become the president of Toro. Why, not even 50, his fellow trustees (a group not known for deference to each other) chose him to succeed John G. Kemeny as Dartmouth's president.

Why the Red Cross depended on him to clean up the bloody mess that the organization found itself in after September 11. Why CBS, in upheaval, fished him out of New Hampshire to straighten things out at headquarters. Why Governor Jeanne Shaheen, confounded by the collision of hard economic facts and New Hampshire's hard-earned reputation as a low-tax haven, placed a call to Newbury to persuade McLaughlin to lead a commission to sort out questions she couldn't, or wouldn't, answer herself. Why McLaughlin, who so loved a fishing expedition and took such delight in the wonders that a spruce fly could accomplish in cold New England waters, was never idle, not for a minute.

He was, we should say at the start, corporate in outlook. The trustees wanted this in a president, the faculty did not, and therein lies the reason why a man who sought consensus often got more contention than he wanted—or expected. He wasn't Dartmouth's first trustee president (that was William Jewett Tucker, class of 1861, who served from 1893 to 1909), nor the Colleges first businessman -president (that was telephone company executive Ernest Martin Hopkins, class of 1901, who served from 1916 to 1945), so the omens (the conscience of Tucker, the vision of Hopkins, all dressed up in Tuck technocracy) were promising. And, let us remember, he was regarded as being the vanguard of a movement on campus at a time—the 1980s—when the financial crunch prompted the ascendancy of the number crunchers. (We didn't know it at the time, but the period would be remembered not for economics but for ideology; it is now recalled for the early stirrings of conservatism on campus.) His business outlook sometimes clashed with the cozy comforts of many of his campus colleagues but the numbers are incontrovertible: He more than doubled the endowment. Some years the alumni contribution rate was in the 67 percent range. Faculty salaries grew by 43 percent. A renewed commitment (when it really mattered, to a principle that really mattered) to need-blind admissions.

It can be said with truth that in the McLaughlin era (1981-87) the landscape of the College changed. Up went the Nel- son A. Rockefeller Center for the Social Sciences. Hood Museum, too. A new boathouse. The Berry Sports Center. New facilities at Tuck and Thayer. The John Sloan Dickey Center for International Un- derstanding, today a yeasty influence on campus, was established. Also the Insti- tute for the Study of Applied and Professional Ethics, a mouthful, but not what the skeptics expected from a fellow who had been bred to business. He engineered a plan to relocate the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital and, perhaps most important given the health-care storm that was only gathering force in his time in Parkhurst, put the Dartmouth Medical School on a firm financial footing.Thankless tasks, some of them. Indispensable, all of them.

With him—an uneasy hostess sometimes but a portrait of grace always—was Judy, wife and mother of Dartmouth students, generous, kind, thoughtful beyond measure. The obituaries of her husband (The New York Times stretched its across four columns) tell about the corporate- board memberships and chairmanships (too many to list), the philanthropic work (no account included it all, in part because a lot of it was done in secret), the times he was summoned to bail out a company or a charity or some politician who thought a man from the New Hampshire forests might not get bogged down in the trees. The facts you need to know are these: McLaughlin grew up in Grand Rapids, went to Dartmouth as a member of the class of 1954, served six years as Dartmouths president, died in August on a fishing trip.

But the remarkable traits of McLaughlin had nothing to do with the facts at all. The remarkable traits couldn't, and can't, be quantified, or captured in an account, all these years later, of the controversies over the alumni magazine's sense of independence, or the furor over the destruction of the campus anti-apartheid shantytown, or the angry debate over ROTC, or the faculty's document contending that McLaughlins leadership style "places the College in real jeopardy," or, for that matter, in a list of his accomplishments (drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles, and many decades later by the Aspen Institute, and given five honorary degrees and appointed to three college boards) or any discussion of the way he enhanced the undergraduate residential system.

The remarkable traits instead are these: He believed in the liberal arts, he believed in the power of an education to transform a life and the world, he believed in friendship and the transforming force of fellowship, he believed in his College because he believed it fostered them all. "He walks the campus," Walter Burke '44, who headed the search committee that selected McLaughlin president, said shortly after the choice was announced, "in a way few people can." He walked the campus, and the College Grant, too, and David Thomas McLaughlin, 14th president of the College, dead in Alaska at 72, left footprints. We see them still.

DAVID M. SHRIBMAN, who completed adecade as a trustee of the College in 2003, is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette He won the Pulitzer Prize in 1995.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

November | December 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

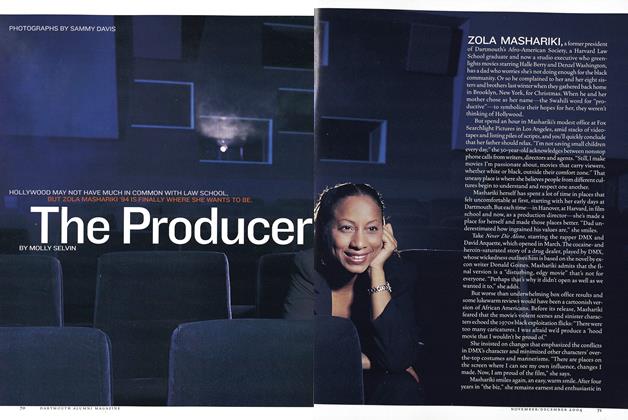

FeatureThe Producer

November | December 2004 By Molly Selvin -

Article

ArticlePresidential Range

November | December 2004 -

Sports

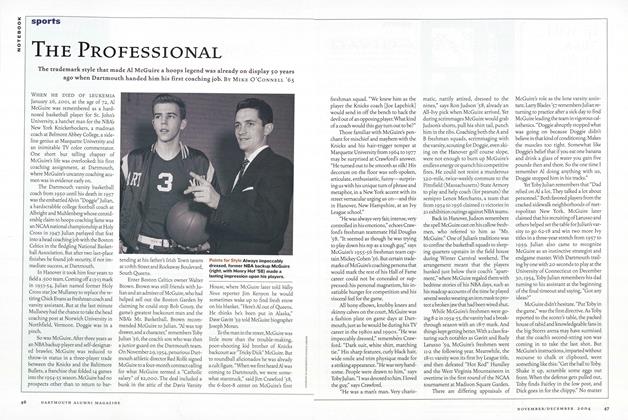

SportsThe Professional

November | December 2004 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Interview

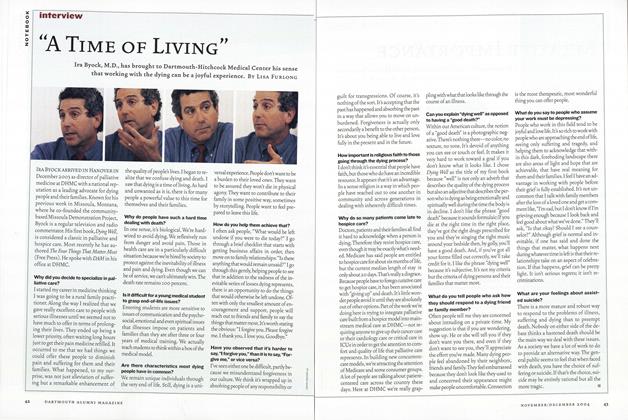

Interview“A Time of Living”

November | December 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionHarpooning a Liberal

November | December 2004 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83

David Shribman ’76

TRIBUTE

-

TRIBUTE

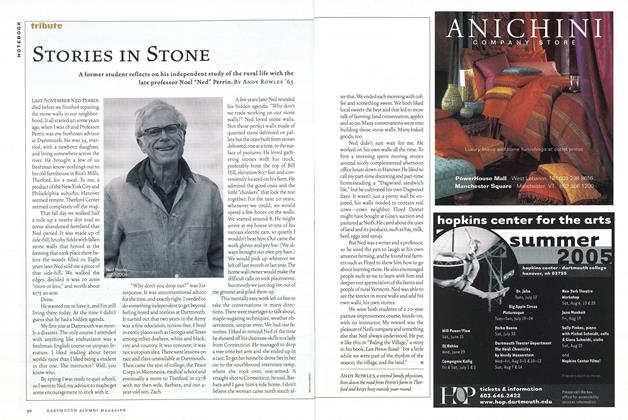

TRIBUTEStories in Stone

May/June 2005 By Andy Rowles ’65 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELuck of the Draw

Nov/Dec 2008 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTENo Quieter Bed

Sept/Oct 2005 By James Zug ’91 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEFishing With George

May/June 2010 By Jim Collins ’84 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTESage on Stage

Mar/Apr 2008 By Mike O’Connell ’65 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELate Fall Practice

Nov/Dec 2006 By Sara E. Quay