From the Halls of Dartmouth College to the Shores of Tripoli

How a feisty and forgotten Dartmouth alum led what might be called the country’s first war on terrorism—more than 200 years ago.

July/August 2007 DAVID T. NUTT ’44 AND ROBERT H. NUTT ’49From the Halls of Dartmouth College to the Shores of Tripoli DAVID T. NUTT ’44 AND ROBERT H. NUTT ’49 July/August 2007

How a feisty and forgotten Dartmouth alum led what might be called the country’s first war on terrorism—more than 200 years ago.

July/August 2007 DAVID T. NUTT ’44 AND ROBERT H. NUTT ’49HOW A FEISTY AND FOR GOOTEN DARTMOUTH ALUM FIRST WAR ON TERRORISM-MORE THAN 200 YEARS AGO.

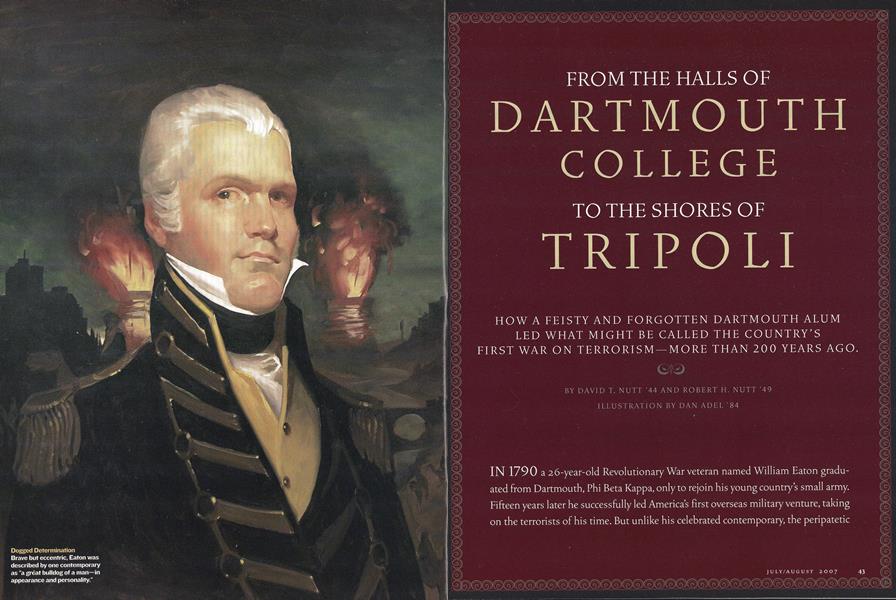

IN 1790 a 26 -year-old Revolutionary War veteran named William Eaton graduated from Dartmouth, Phi Beta Kappa, only to rejoin his young country's small army. Fifteen years later he successfully led Americas first overseas military venture, taking on the terrorists of his time. But unlike his celebrated contemporary, the peripatetic John Ledyard, class of 1776, Eaton is a forgotten man.

His remarkable story involves Muslim terrorists, white slavery, blackmail and political intrigue. Its centerpiece was Eaton's campaign in 1805 to rescue more than 300 American hostages held in monstrous circumstances by the notorious Barbary pirates of North Africa.

With almost no money and under ambiguous orders from President Thomas Jefferson, Eaton assembled a ragtag army of Greek and Turkish mercenaries, Arab tribesmen led by volatile sheiks, 107 camels and eight U.S. Marines. He marched this odd band of warriors across 500 miles of North African desert, from Alexandria toward Tripoli. Along the way he encountered sandstorms, treachery, language barriers, religious conflicts, debilitating thirst and hunger and, finally, injury.

Luckily, his life up to that point had prepared him for the worst. Before he even contemplated college, 16-year-old William Eaton had run away from his Connecticut home in 1780 to join Washington's army. Despite suffering a leg wound, he stayed on till war's end, rising to the rank of sergeant. In 1783 he enrolled at Dartmouth. He was 19; the College was 14. The young veteran earned his tuition by teaching, which delayed his graduation by three years.

At Dartmouth Eaton earned a reputation for eccentricity and bravery. The Eaton file at Rauner Library includes a story that has him disarming a thief "wielding a dirk." In another he "scourged" an uncouth man who had insulted a fair maiden. Always a man to reckon with, Eaton hated injustice.

During one absence to earn tuition money, he displayed some uncertainty about his future, writing to Dartmouth President John Wheelock: "I shudder to find myself so near an active stage in my life, and so little qualified for usefulness."

Nevertheless, in his small class of 31 Eaton was one of 13 to graduate Phi Beta Kappa. During a brief post-graduation clerkship in the Vermont House of Delegates, Eaton found the first of several patrons, Gen. Stephen R. Bradley, a U.S. senator from Vermont, who in 1792 used his connections to get Eaton an appointment as a captain in the U.S. Army. So, while most of his classmates became ministers or doctors, Eaton was back in the Army.

His decision quickly foreclosed the courtship of his Haverhill, New Hampshire, girlfriend. When she rejected the would-be soldier, the usually gallant Eaton replied, "I prefer the field of Mars to the bower of Venus." That same year the 28-year-old Eaton found a wife who understood the soldier's life. He married Eliza Sykes, the young widow of a Revolutionary War general from Brimfield, Massachusetts. Despite frequent absences the young officer managed to sire three girls and two boys.

While serving as an officer under Gen. "Mad Anthony" Wayne during the campaign against Ohio Indians in 1794, Eaton came to idolize and emulate his charismatic 47-year-old leader. "When in danger he is in his element and never shows to so good advantage as when leading a charge," Eaton wrote. "He endures fatigue and hardship with a fortitude uncommon to men of his years....I have seen him in the most severe night of winter sleep on the ground like his fellow soldier."

The combative Eaton excelled at making enemies. Nevertheless, his complete lack of guile, along with his total honesty and openness in dealing with both subordinates and superiors, sometimes helped him. When he reported a shady land deal offered him by a colonel, blowing the whistle brought him first a court-martialhis conviction was later expunged—and then a prestigious appointment from his next patron, President John Adams' Secretary of State Timothy Pickering. In 1798 Pickering rewarded Eaton's diligence, loyalty and efficiency by naming him consul to Tunis. His 15 minutes of fame were on the horizon.

Eaton was appalled by the circumstances he found on the coast of North Africa. Pirates from the Barbary states—Algiers, Morocco, Tunis and Tripoli—routinely captured and ransomed ships and took prisoners, at least some of whom were sold into slavery. Pasha Yussef Karamanli, the barbarous ruler of Tripoli, was, according to Eaton, an "elevated brute." Europe's maritime countries paid millions in gold to prevent interception by Barbary pirates answering to Yussef and other despots.

Long before it was a popular position, Eaton believed that any slavery was evil. In a letter to his wife he wrote, "Barbary is hell So alas, is all America south of Pennsylvania; for oppression, and slavery...."

Eaton reckoned that a military solution was needed. "There is but one language which can be held to these people," Eaton wrote, "and this is terror." President Jefferson agreed. "I know nothing will stop the eternal increase from these pirates but the presence of an armed force," he wrote to Secretary of State James Madison. But the president was hard put for funds. His administration still faced $75 million in Revolutionary War debts, and in 1803 the debt increased when the country acquired the Louisiana Purchase from France for $15 million.

Ever the soldier, the new consul in Tunis was called on for diplomatic skills beyond his blunt, straightforward approach to problems. The biggest of these was the crisis triggered by the imprisonment of 307 crewmembers of the USS Philadelphia, which in October 1803 ran aground in the harbor of Tripoli, several hundred miles down the Mediterranean coast to the east of Tunis. Pasha Yussef capitalized on the ships plight, forcing the sailors into slave labor.

At the time Eaton was in Washington, seeking reimbursement of $5,000 he had borrowed to ransom a 12-year-old Sardinian girl of noble birth and for funds he had used to commission and arm a merchant vessel in order to suggest a U.S. naval presence to thwart rampant piracy. Jefferson decided that Eaton, no matter how patriotic, had overreached. He denied Eaton's claims.

Eaton chafed at the rebuff. But in March of 1804, when news of the hostage-taking finally reached Washington, the government was in shock. Action was critical to establish the young country's international credentials.

Despite their differences, Eaton quickly gained Jefferson's permission to return to the Barbary Coast as a "naval agent" with a small force of warships. Both hoped that a threat of force would convince the pasha to free all the hostages taken from the Philadelphia and ultimately put the pirates out of business.

Diplomatic chicanery and the antipathy of more than a few high-ranking naval officers eventually hamstrung the mission. Eaton's lack of finesse did little to advance its success. The Navy brass heading the task force appointed to support Eaton's mission disliked the plans and found many reasons for delay. After all, Eaton was Army, not Navy.

During his time as consul Eaton had, however, become friendly with Pasha Hamet Karamanli, the legitimate ruler of Tripoli driven into exile by his younger brother, the violent Yussef. Together, Eaton and Hamet plotted to assemble an army in Alexandria and march on Tripoli. When Eaton presented this plan to Jefferson on a second trip to Washington, the president did not discourage it, but he could not assure Eaton of anything close to the $100.000 in cash and munitions that was needed. Meanwhile, those 307 Americans were suffering in captivity.

Back in the Mediterranean, Eaton once again borrowed—from several sources and against sketchy assets—in order to fund his army of mercenaries in Alexandria. He petitioned the Navy for 100 Marines (back then Marines constituted a small combat force that traveled aboard U.S. Navy vessels), but had to settle for eight. They joined nearly 400 men, mostly Arabs, Turks and Greeks, to make the onetime New England schoolteacher the enterprising leader of the first overseas military venture by the still young United States of America.

If assembling the army was difficult, keeping it together was close to impossible. But after six weeks of near disasters from hunger, thirst, threatened desertions, cultural impasses, religious friction, unruly camels and the infamous siroccos of the rugged North African desert, Eaton's checkered crew reached the coastal city of Derne. Well short of Tripoli, this was an important and well-defended port in what is now Libya. Eaton demanded that the local governor surrender. The answer: "My head or yours." Eaton drew his sword.

Remarkably, his makeshift militia needed only a few days of shelling before capturing Derne. Initially, two Marines were killed. There were a series of counterattacks and Some 60 of Eaton's men were lost. Finally, despite a serious wound to his left wrist, "General" Eaton, as his troops elected to call him, saw the American flag fly for the first time over foreign soil. What's more, Eaton was convinced his small army could conquer all of Tripoli and restore its rightful ruler, Hamet, who would treat the United States as a true ally.

While Eaton's army was struggling across the desert a new emissary from Washington, Tobias Lear, had been named consul general to the Barbary States. Without informing Eaton, Lear, who at one time had been secretary to George Washington, negotiated a treaty with Tripoli. It paid the pasha $60,000 in ransom for the Philadelphia hostages. (Yussefs original demand had been for $1,690,000, more than Jefferson's entire military budget.)

Soon after, Eaton's army of mercenaries and Marines was disbanded and the disappointed "General" left for home, furious at his country's capitulation on the cusp of victory. His triumph at Derne had, however, enchanted the press and he received a hero's welcome on his return. Massachusetts rewarded him with 10,000 acres (in Maine, then part of Massachusetts). Derne Street, in the heart of Boston, was given that name to honor Eaton's battle. But despite months of negotiating, the government in Washington never fully reimbursed Eaton for all the debts he had incurred in fighting the country's first war on terrorism.

Jefferson lauded Lear's success and downgraded Eaton's enterprise. "The ground he [Eaton] has taken [is] different, not only from our views, but from those expressed by himself on former occasions," wrote Jefferson in an early example of presidential spin.

Eaton retired to Brimfield and found solace in strong drink and gambling, only to return to brief notoriety when Aaron Burr tried to enlist him in his conspiracy to annex Western territories. Once again Eaton blew the whistle, going straight to Jefferson. Unfortunately, politics trumped justice and Burr went free, much to the dismay of both Jefferson and Eaton. Jefferson, however, didn't see fit to reward Eaton for his loyalty. Meanwhile Eaton lost all the wagers he had placed on Burr being convicted. He returned to Massachusetts, where he died in 1811, at 47; disillusioned and still in debt.

Until the recent publication of several books, Eaton's heroic leadership in a dangerous international adventure had been pretty much relegated to the dustbin of history. Seventy years ago DAM printed a brief summary of Eaton's career in which William Krieg '35 summed up Eaton's legacy: "Had Eaton shown less independence of spirit and an ability to bridle his tongue, he might have received at the hands of a grateful country the credit due, when, as an infant nation scarcely 10 years old, it was endeavoring to play the treacherous game of European power politics. But the headstrong Eaton, with his caustic criticisms, made enemies in influential quarters who kept him in hot water during most of his career."

Since 9/11 Americans have taken up greater interest in the Middle East and the history of U.S. involvement there, and Eaton's feats are more relevant than ever. Three authors have dusted off the Eaton story to produce three books: The Pirate Coast by Richard Zacks (Hyperion, 2005), Power, Faith and Fantasy by Michael B. Oren (Norton, 2007), and Reviewing Victory in Tripoli: Flow America's War with the Barhary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation by Joshua E. London (John Wiley & Sons, 2005). The scope of Oren's book extends well beyond Eaton, but the other two provide extensive details of Eaton's covert operation. According to The New York Times, Zacks gives Eaton "a fully deserved hero's treatment."

With that, the feisty diplomat is perhaps finally earning a place in history beyond that line in the Marines Corps hymn. IS

HE FAMOUS LINE—"TO THE SHORES OF TRIPOLI"—IN THE MARINE CORPS HYMN COMMEMORATES EATON'S DARING 500-MILE EXPEDITION ACROSS THE EGYPTIAN DESERT

DAVID T. NUTT, a retired marketing executive and freelance writer, livesin Watchung, New Jersey. His brother ROBERT H. NUTT of Norwich, Vermont, is a longtime DAM contributing editor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

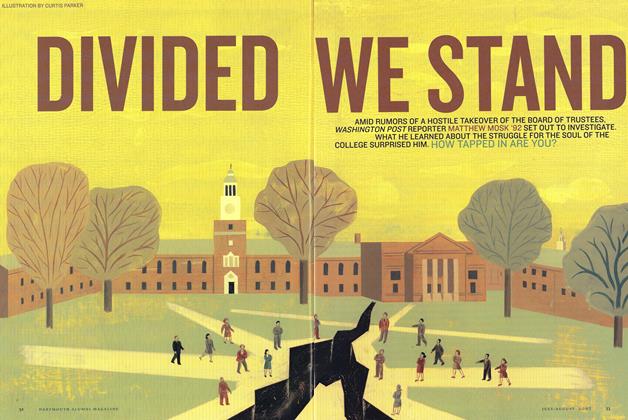

Cover StoryDivided We Stand

July | August 2007 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

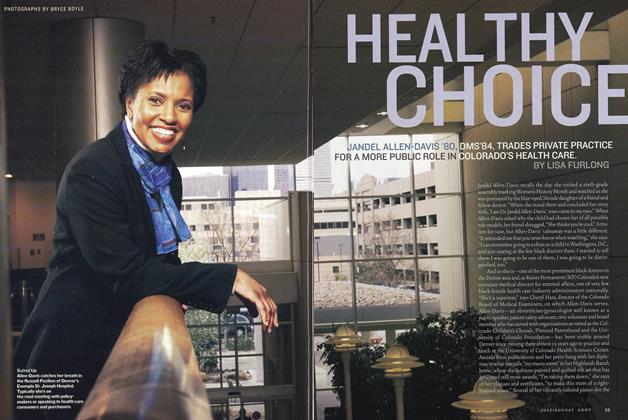

FeatureHealthy Choice

July | August 2007 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2007 By BONNIE BARBER -

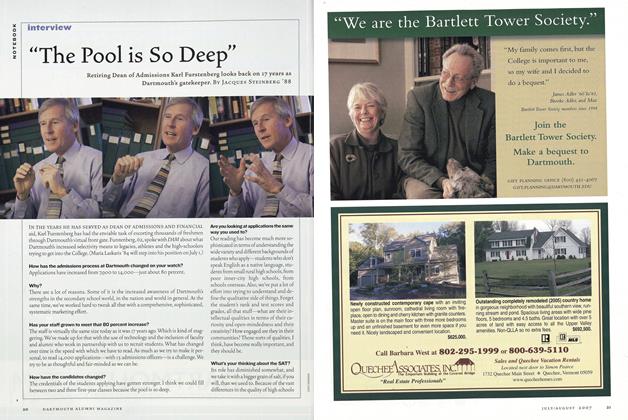

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“The Pool is So Deep”

July | August 2007 By Jacques Steinberg ’88

Features

-

Feature

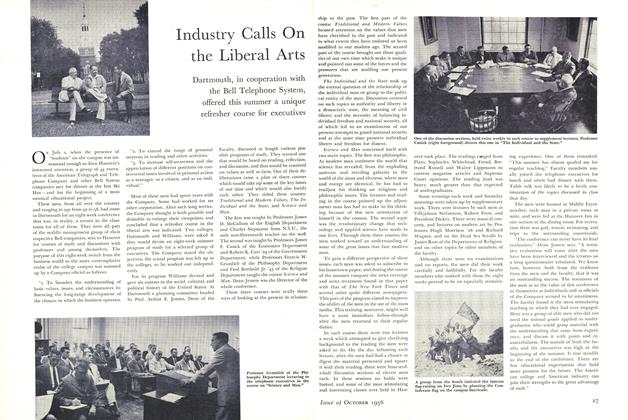

FeatureIndustry Galls On the Liberal Arts

October 1956 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May/June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

FeatureOn a Scale of 1 to 10...

DECEMBER 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeatureConscience or Compromise

July 1961 By HARRIS BONAR McKEE '61 -

Cover Story

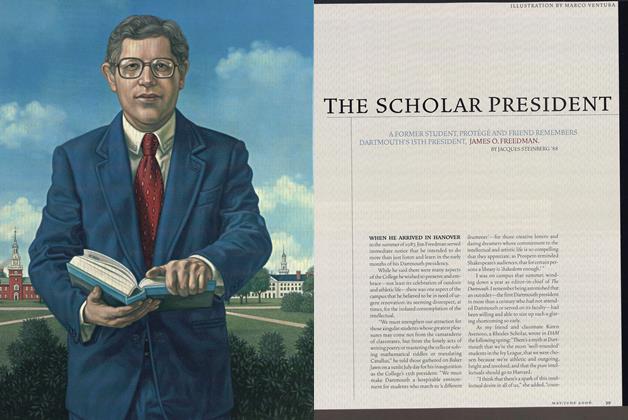

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

May/June 2006 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

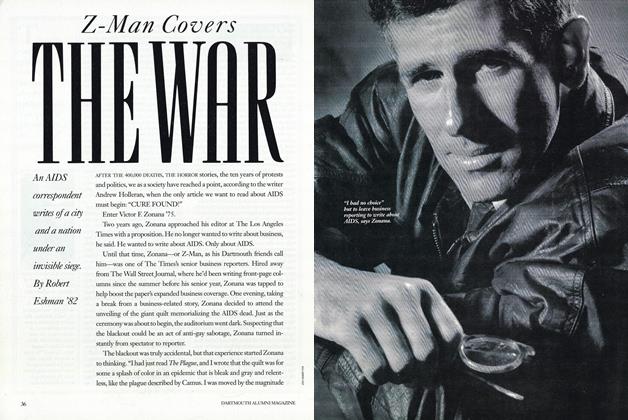

FeatureZ-Man Covers The War

FEBRUARY 1991 By Robert Eshman '82