From Town to Gown

A childhood spent in Hanover allowed one future alum to start his College life earlier than most.

July/August 2007 John W. Norton ’50A childhood spent in Hanover allowed one future alum to start his College life earlier than most.

July/August 2007 John W. Norton ’50A childhood spent in Hanover allowed one future alum to start his College life earlier than most.

WHEN THE TIME CAME FOR ME TO APPLY TO COLLEGE, I DIDN'T HAVE TO think twice about where I wanted to go. I had always assumed Dartmouth would be the place for me, a great place to continue growing. I had spent my life in Hanover but had no desire to get out of town. I didn't apply anywhere else.

Hanover in the 1930s and 1940s was a wonderful place to grow up. The population was about 3,000, nearly doubling with a student body of 2,500. On Fall House Party, Carnival or Green Key weekends, about 2,000 dates were added.

The town was small enough that you could walk or ride a bicycle to most destinations. There were few student cars—no traffic lights or parking meters needed.

My family lived on Choate Road. My father, Max, graduated from Dartmouth in 1919, then stayed on to work for the College. He was graduate manager of athletics, then the Colleges first bursar and subsequently its assistant treasurer.

My sisters and I attended the town's public schools. Our education was enriched by the exhibits of Wilson Museum, the newly painted Orozco murals, concerts in Webster Hall, Dartmouth Players productions in Robinson Hall and research in Baker Library. Climbing Bartlett Tower was a bonus, and intramural and intercollegiate athletic events were great treats. Chinese culture professor Wing-Tsit Chan spoke to us about "Youth and World Peace" at our graduation from Hanover High.

Professors were always part of the landscape. At the annual Christmas pageant in Rollins Chapel, the highlight for me was the procession of the three kings to the manger, led by the singing of English professor Edmund Booth. Something even better happened when I was 12. It was the Fourth of July, and Jim Pressey (son of English professor Benfield Pressey) and I were casually lighting and tossing 1-inch firecrackers from his front steps on Parkway. To our surprise Gordon Ferrie Hull, a distinguished professor of physics and a neighbor of the Presseys, stopped to inquire if we would like to add a little technology to our entertainment. Professor Hull drove us to the physics lab, where he handed us a small wooden box with two electrical terminals and two long wires protruding from the top. Thus armed, we returned to Jims house. We put the box near the sidewalk, placed a firecracker between the terminals, ran the wires 40 feet back to the house and waited for our first unsuspecting pedestrian. Foot traffic was not heavy on Parkway, however, and we soon turned to blowing up cherry bombs. Memory dims, but I believe we returned the box to Professor Hull without its wooden top.

Dartmouth students made the greatest impression on Hanover kids. When we went to the movies at the Nugget theater, for example, we always sat in the back row, hoping the students would start a peanutthrowing war—providing us a free treat as peanuts ricocheted off the back wall. The classic scene of a starlet taking a bath in an old Western film, with the soapsuds at sufficient height to avoid censorship, was inevitably followed by a student voice from an orchestra seat calling out, "How's it look from the balcony?"

We also had plenty of role models from the Dartmouth teams. I would walk over to Memorial Field after grade school, meet my grandfather and watch coach Jeff Tesreaus baseball teams. Hal "Big Chief" Wonson '40 was my idol—a pitcher who could hit home runs. When we kids couldn't muster enough players for a baseball game, as few as three of us could play our version of baseball off the gym steps. The batter threw a tennis ball off the steps, using side arm off the risers for line drives or overhand off the step edge for long home runs. Two or more fielders covered the broad sidewalk leading out to Wheelock Street. The sidewalk partitions demarcated singles close to the steps and extra base hits further out. The batter's success depended on getting the ball to land where a fielder couldn't catch it.

I was at the famous "fifth-down" football game against Cornell in 1940 (in which Cornell scored the only touchdown on a drive during which officials mistakenly awarded them an extra down) and later that week joined the student torchlight parade to the Presidents House to hear President Ernest Martin Hopkins, class of 1901, read the concession letter from his counterpart at Cornell giving Dartmouth a 3-0 victory. Away football games were brought to Hanover byway of the "grid graph." A large footballshaped green board was set up in the gym's west wing. Its center was a translucent panel, marked to resemble a football field. Around this field were signs for downs, yards to go, pass, punt, etc., each with its own light. The operator stood behind the board and received his play-byplay information by telephone. He would light the appropriate sign and then use a flashlight behind the field to reflect the progress of the ball. What fun!

Music provided another connection to students. When I started clarinet lessons in seventh grade, Clay Messinger 41 was my teacher. Later I studied with Norm Rian and Frank Lawlor, each of whom directed the Dartmouth band and helped out with music programs in the Hanover schools. With the College student body depleted by war, mustering a band to play for the Wednesday Navy V-12 parades on campus was difficult. Four or five of us from Hanover High were recruited to play in the band and traveled by train to play at some away football games. The band uniform was not the traditional casual green sweaters and'white flannel pants, but military-style jackets and hats, which was heady stuff for high-schoolers.

With the end of the war the campus was flooded with returning veterans. Many were married, and Hanover was stretched to accommodate them. As bursar for the College, my father was involved in arranging for married students' housing. Two of the Fayerweather dorms were converted and two temporary complexes were built- Sachem and Wigwam Villages. With housing at such a premium, my family welcomed Carol and Bob Allen 45 to an apartment at our house. My father also assisted the wives in finding jobs. His cohorts in the administration dubbed him Dartmouth's "First Dean of Women"—a title he thoroughly enjoyed earning.

In the fall of 1946 I was privileged to at last become a Dartmouth student, matriculating as President John Dickey 29 welcomed his first freshman class. About three-quarters of my class was composed of returning veterans, an awesome experience for the rest of us entering directly from secondary schools. Anywhere else I might have found this intimidating, but I was fortunate to be on familiar territory. With the hill winds already in my veins and the granite of New Hampshire in my brains, I was home.

"Hal 'Big Chief' Wonson '40 was my idol—a pitcher who could hit home runs."

JOHN W. NORTON, a retired hospital president and CEO, lives in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

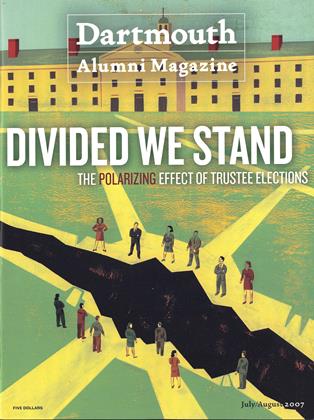

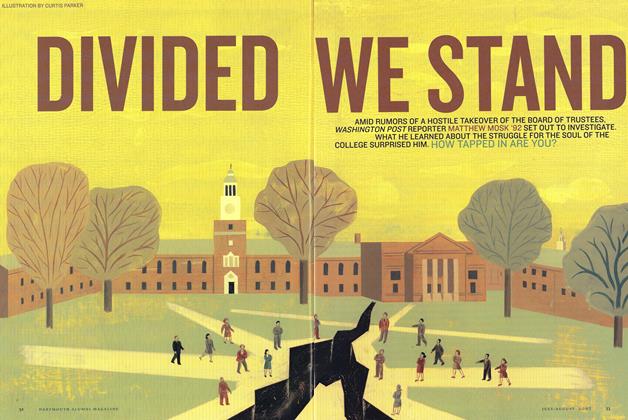

Cover Story

Cover StoryDivided We Stand

July | August 2007 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

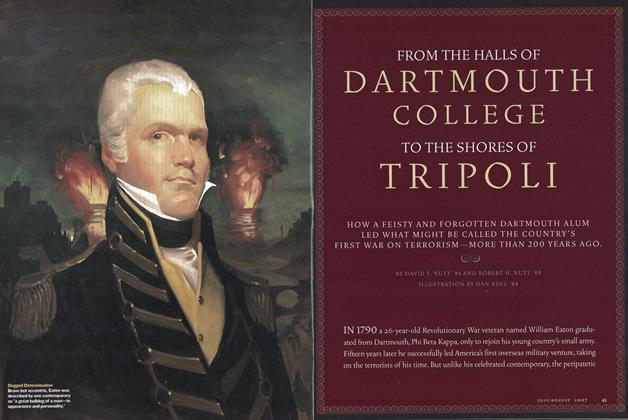

Feature

FeatureFrom the Halls of Dartmouth College to the Shores of Tripoli

July | August 2007 By DAVID T. NUTT ’44 AND ROBERT H. NUTT ’49 -

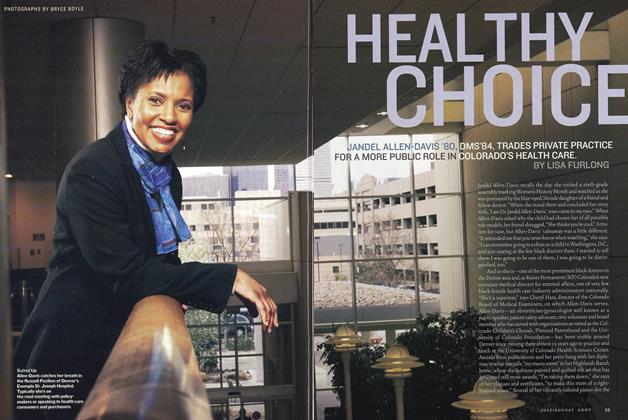

Feature

FeatureHealthy Choice

July | August 2007 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2007 By BONNIE BARBER

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGetting the Picture

May/June 2008 By Andrew Mulligan ’05 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryReminiscing In Tempo

May/June 2003 By Cliff Ennico ’75 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Pursuit of Happiness

May/June 2007 By Daniel Becker ’84 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut of Control

Mar/Apr 2005 By Lance Roberts ’66 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

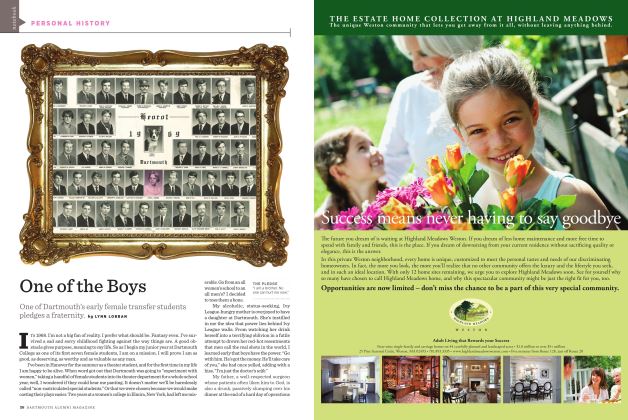

PERSONAL HISTORYOne of the Boys

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By LYNN LOBBAN -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYWhat is Perfect?

Sept/Oct 2000 By Mary Cleary Kiely ’79