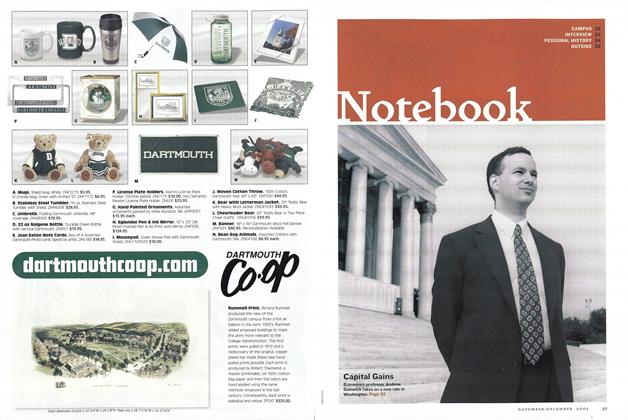

“A Privileged Position”

A Dartmouth prof applies his research inside the Beltway by joining the president’s Council of Economic Advisors.

Nov/Dec 2003 Charles Wheelan ’88A Dartmouth prof applies his research inside the Beltway by joining the president’s Council of Economic Advisors.

Nov/Dec 2003 Charles Wheelan ’88A Dartmouth prof applies his research inside the Beltway by joining the president's Council of Economic Advisors.

With a presidential election looming on the horizon and budget deficits and the costs of rebuilding Iraq clamoring for attention, professor of economics Andrew Samwick has plunged into the world of White House economic policy. In July Samwick, 33, took leave from the College to serve as chief economist on the staff of President Bush's Council of Economic Advisors (CEA), a body created in 1946 to provide the president with "objective analysis and advice" on domestic and international economic policy issues. Samwick, a member of the Dartmouth economics department since 1994, has written extensively on the Social Security system (www. dartmouth.edu/~samwick). He recently spoke to DAW by phone from his office in Washington.

Is it fair to say you're giving advice tothe people who are giving advice tothe president?

That's actually a perfect way to say it. My boss is Greg Mankiw, who is the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, and he meets with the president quite frequently to discuss how the economy is doing.

Are there Democratic economists andRepublican economists?

All economists are more similar to each other than they are to anybody else. But what tends to get reported is their differences. There are some economists who are Republican in their outlook on things like the size of government, on whether efficiency gains from a smaller government are a worthwhile objective to pursue. Then there are Democratic economists, who generally believe that there is more scope for productive government involvement in economic activity. As it pertains to how we would teach, the differences are probably quite small; as it pertains to politics, they tend to get exaggerated.

There is an old saw that Harry Trumanwanted a one-armed economist so hewould never be able to say, "On theother hand...." Is the White House getting conflicting economic advice, andif so, is that necessarily a bad thing?

If Harry Truman were alive today, he wouldn't allow us even that one hand. In the present White House, it seems there is good communication that flows among the three principal entities: the CEA and the National Economic Council, Treasury, and the Office of Management and Budget. There are typically no big disagreements about facts like costs. As you get further away from economic facts and more into politics—like trying to gauge support for something in Congress—you tend to find more disagreement.

So why was the White House interestedin you?

It's the invisible hand—you never have to know why somebody wants you, only that they want you. If I had to pick one thing that would cause my name to appear high on their list, it would be all the work I had done on Social Security.

What's the most intractable economic problem facing the country?

A government is the steward for generations yet to be born; it's their protector in a lot of ways, whether it's the environment or fiscal policy. A good system of accountability for thinking about tradeoffs over time is always the most difficult problem a government faces. Even when I was an undergrad, problems related to moving resources over time—general problems of savings—seemed to be the most challenging.That naturally led to the work I did on Social Security and pensions. It's not so straightforward to figure out that I should restrain consumption today in favor of consumption tomorrow, even at the individual level. It's even tougher as an organization moves from an individual to a family to a local government all the way up to the whole country. It becomes even more difficult for the entire country when there are political elements that weigh in, questioning whether it's more appropriate to save now or make another generation pay later.

Do you find your ideas getting stifledby Washington bureaucracy?

I consider myself to be in a privileged position; the CEAis part of the executive office of the president. That's very close to where decisions get made. There are ample opportunities to have my individual ideas and opinions vetted at the appropriate level and to make their way up, if they're good ideas. It seems like everybody works very hard and everybody looks to do as much work as they possibly can. That's not the traditional picture people on the outside have of the government.

What do you think you'll bring backfrom this job to Hanover in terms ofyour research and your teaching?

When you just stay in academia it's tempting to continue to work on the same sort of things and address the same sorts of questions. I think I'm less like that than other people in general, but coming here has helped me think about some other topics that might be useful to work on. I've written a lot about things the government could do if it wanted to improve the way it handles entitlements. To have the opportunity to come down here and say it directly to the people who make those decisions—I don't think I could have lived with myself professionally if I didn't do that.

How does the culture of the Bush administration differ from that of academia?

The most striking difference, and this is not particular to one administration, is the horizon over which things have to get done. I see many more deadlines, and they are typically quite immediate.

Do you ever get face time with thepresident?

I haven't met the president yet. His time is much too scarce to meet regularly with anyone but the principals from any organization within the executive office.

Andrew Samwick

Charles Wheelan is director of policyand communications for Chicago Metropolis2020, a nonprofit organization advocatingbetter regional policies in the Chicagoarea. He is a former correspondent for The Economist

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Overtreated American

November | December 2003 By SHANNON BROWNLEE -

Feature

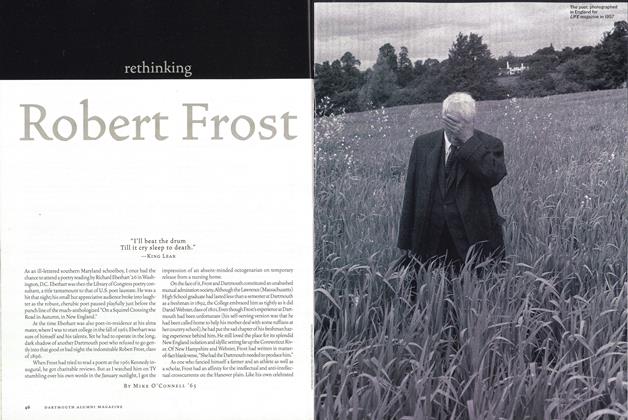

FeatureRethinking Robert Frost

November | December 2003 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Feature

FeatureSimply Seth

November | December 2003 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2003 By DAVID DEAL, DAVID DEAL -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2003 By John Kemp Lee '78, THE KOUROS GALLERY, NYC -

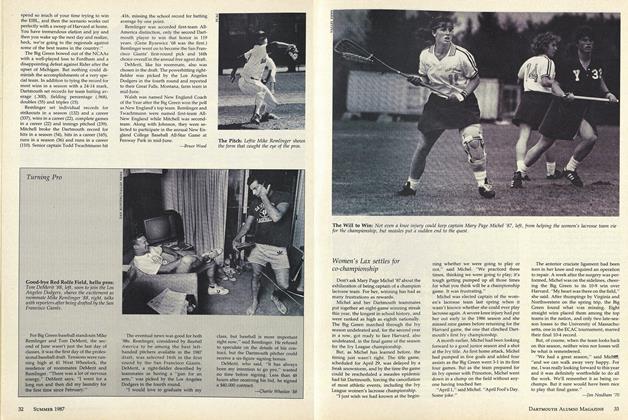

Personal History

Personal HistoryBody Of Knowledge

November | December 2003 By Kirsten Andrews ’97

Charles Wheelan ’88

-

Sports

SportsTurning Pro

June 1987 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

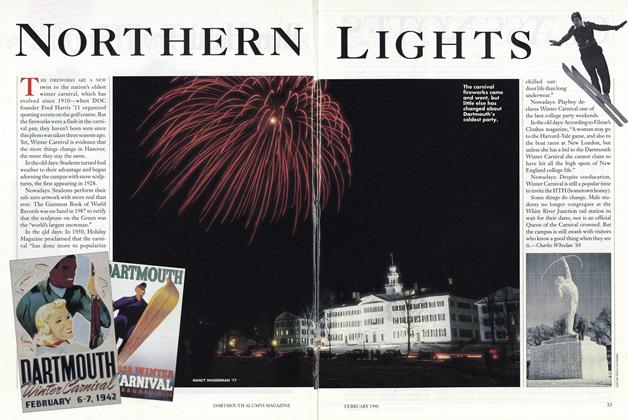

Feature

FeatureNorthern Lights

FEBRUARY 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

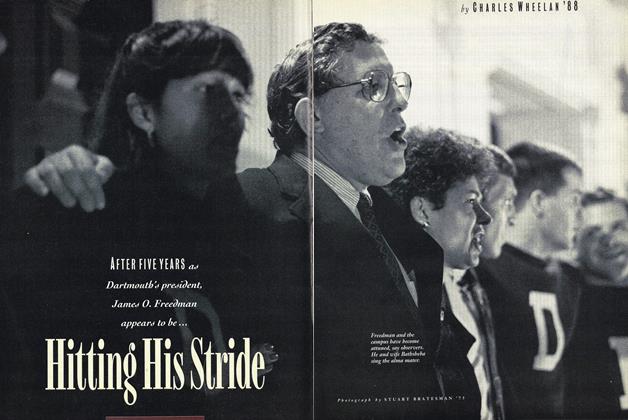

FeatureHitting His Stride

February 1992 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

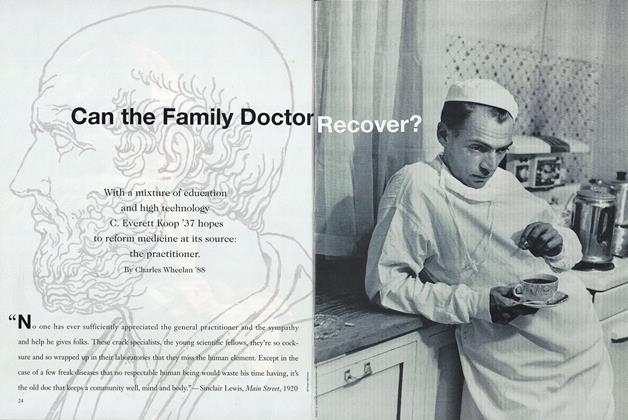

Cover Story

Cover StoryCan the Family Doctor Recover?

NOVEMBER 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionDollars and Sense

Jan/Feb 2004 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleReel Economics

September | October 2013 By Charles Wheelan ’88

Interviews

-

Interview

Interview“It Has Been a Difficult Year”

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2021 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Interview

Interview“This is the Right Fit”

Sept/Oct 2011 By Lauren Vespoli ’13 -

Interview

InterviewQ & A

July/August 2007 By Lisa Furlong -

Interview

InterviewQ & A

Jan/Feb 2008 By Lisa Furlong -

Interview

Interview"Nuanced Decisions"

May/June 2011 By Lisa Furlong -

Interview

InterviewQ & A

Jan/Feb 2004 By Sue DuBois '05