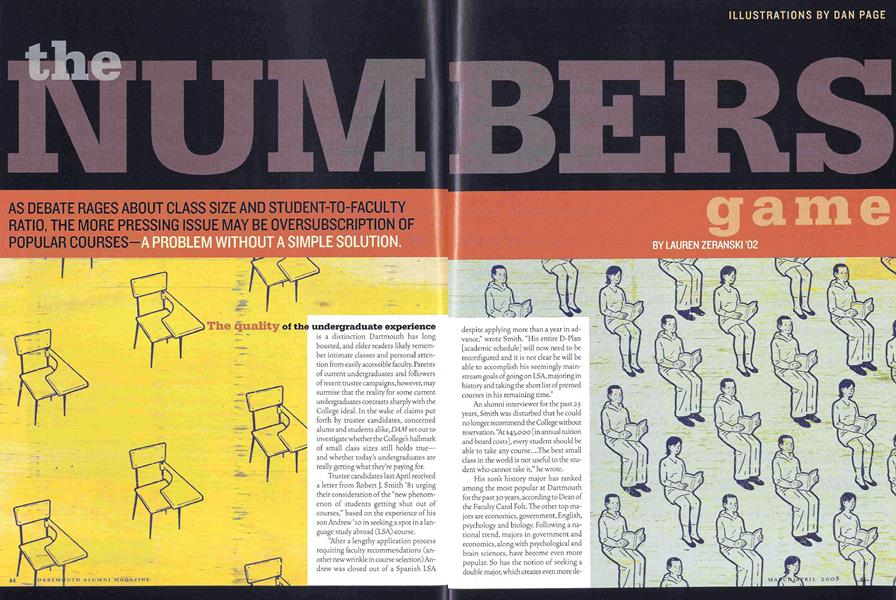

The Numbers Game

As debate rages about class size and student-to-faculty ratio, the more pressing issue may be oversubscription of popular courses—a problem without a simple solution.

Mar/Apr 2008 LAUREN ZERANSKI ’02As debate rages about class size and student-to-faculty ratio, the more pressing issue may be oversubscription of popular courses—a problem without a simple solution.

Mar/Apr 2008 LAUREN ZERANSKI ’02AS DEBATE RAGES ABOUT CLASS SIZE AND STUDENT-TO-FACULTY RATIO, THE MORE PRESSING ISSUE MAY BE OVERSUBSCRIPTION OF POPULAR-A PROBLEM WITHOUT A SIMPLE SOLUTION.

The. quality of the undergraduate experience is a distinction Dartmouth has long boasted, and older readers likely remember intimate classes and personal attention from easily accessible faculty. Parents of current undergraduates and followers of recent trustee campaigns, however, may surmise that the reality for some current undergraduates contrasts sharply with the College ideal. In the wake of claims put forth by trustee candidates, concerned alums and students alike, DAM set out to investigate whether the Colleges hallmark of small class sizes still holds trueand whether todays undergraduates are really getting what they're paying for.

Trustee candidates last April received a letter from Robert J. Smith 'Bl urging their consideration of the "new phenomenon of students getting shut out of courses," based on the experience of his son Andrew '10 in seeking a spot in a language study abroad (LSA) course.

"After a lengthy application process requiring faculty recommendations (another new wrinkle in course selection) Andrew was closed out of a Spanish LSA despite applying more than a year in advance," wrote Smith. "His entire D-Plan [academic schedule] will now need to be reconfigured and it is not clear he will be able to accomplish his seemingly mainstream goals of going on LSA, majoring in history and taking the short list of premed courses in his remaining time."

An alumni interviewer for the past 25 years, Smith was disturbed that he could no longer recommend the College without reservation. 'At $43,000 [in annual tuition and board costs], every student should be able to take any course....The best small class in the world is not useful to the student who cannot take it," he wrote.

His sons history major has ranked among the most popular at Dartmouth for the past 30 years, according to Dean of the Faculty Carol Folt. The other top majors are economics, government, English, psychology and biology. Following a national trend, majors in government and economics, along with psychological and brain sciences, have become even more popular. So has the notion of seeking a double major, which creates even more de demand—and subsequent closeouts-for certain courses.

Another factor in class size and enrollment is that teaching mandates dropped from five classes per year to four under President James O. Freedman-when President Jim Wright was dean of the faculty—and later to three for science faculty. This reduction put us in line with the teaching loads at our peer institutions," says Associate Dean of the Faculty jane Carroll.

"We may have aggravated the class availability problem by cutting the class load over the last two decades, but the solution is not to increase the teaching load," says trustee T.J. Rodgers '70. It is well documented in the literature that the teachers who also do research do a better job of teaching. We simply need to hire more faculty in the departments that are oversubscribed."

IT'S NICE TO BE POPULAR

Introductory courses in government are capped at 50. Last year some of these listings had at least that many hopefuls on the waitlist. Upper-class seminars capped at 16 had as many as 57 students waiting. Oversubscription for seminars, according to government chair William Wohlforth, is "very, very acute. It's nice to be popular, but it's a very unpleasant task to have to kick people out of your classes. It wears you down. It's not fun." One of the reasons overenrollment causes such a huge cry, says Wohlforth, is that, People really want or need to take a class, and others get in who don't care as much, and that's a shame."

Government course offerings were increased from 84 to 87 in 2005-06 and to 92 this year, temporarily, due to enrollment pres sures. Enrollment caps are decided by individual faculty in conjunction with the department and are based on the best pedagogical way to teach course material. The average percentage of government courses at or slightly above caps in the past two years was 30 percent—not a bad rate. "Of course, the reason you hear horror stories is that certain classes or types of classes get huge pressure," says Wohlforth. "Sixty percent of courses on international relations, for example, were at or above caps in 2005 to 2007. And that figure does not tell you how many students were 'bumped,' that is, just could not get into a class. Often these bump lists can exceed 100 students for one class. And if a student is interested in, say, international relations, they can get bumped from preferred classes many terms in a row, which leads to some disgruntlement."

To alleviate this concern the department adopted a matching system for seminars, requiring students to explain their interest in particular listings before enrolling them. While tenure-track positions in government grew approximately from 20 to 25 since 2000, Wohlforth points out that this increase "does not necessarily mean more courses. Because of new hires we have dramatically reduced the use of [visiting professors]."

SUPPLY AND DEMAND

In economics, with 453 students registered as majors, minors or modified majors, students get closed out of as many as 20 percent of their course choices, a rate that far exceeds the 3.5 percent of closeouts campuswide, as estimated by Folt.

Nonetheless, lines out the door and long waitlists in the econ department were the subject of an October article in The Dartmouth, which also described the fall's last-minute addition of two extra sections of developmental economics.

Due to student interest and applicable research by newly hired faculty, the department added a two-course developmental economics sequence, Econ 24 and 44. Sections of Econ 24, in keeping with department guidelines, should be capped at 35 students. The department anticipated needing four sections, and at least two sections of the related upper-class research seminar. The dean's office allocated economics two fewer sections than requested, one less of each course. "More students showed up in one section of Econ 24 in fall 2007 than we expected for the entire year in all Econ 24 sections combined," recalls professor Eric Edmonds. Folt gave emergency approval for additional sections to accommodate more students, including seniors hoping to take Econ 44 as their major culminating experience.

Edmonds, who by College standards should be teaching four classes a year,will now teach six. "If sections had been added in anticipation of student demands we could have staffed them with other faculty," he says. "Our estimates were low, but we'd been given one less Econ 24 class than we anticipated needing. The additional sections added after the start of the term allowed us to keep class sizes down—if still too large-but there is a cost to the students of having one faculty member with so many classes and students."

The College has a formula that usually helps avoid such overbooking among faculty. For every full-time employee (FTE) in the humanities and social sciences, four courses are allotted; in the sciences, three courses are allotted per FTE. A humanities department with 20 FTEs would be allotted 80 sections. Edmonds believes there is a problem with this system. "The economics department is suffering because we have too few courses offered. An intermediate economics class is considered empty when it has only30 students in it. I feel a bit jealous of others and bad for my students when I walk past a classroom [in another department] with one faculty and two students on my way to teach 40-plus students in one of my sections."

Like government, the economics department has devised some strategies to cope with increasing demand. Waitlists may be long, but to ensure that students with greatest need are able to enroll, the department now sends e-mails reminding majors and minors to sign up for outstanding requirements, listing which terms courses are offered and urging registration by deadline.

Econ chair Patricia Anderson, who recommends that students practice greater planning and flexibility during enrollments, says there are two aspects to every waitlist: students who are bumped who never try to enroll again and others—usually 10 or 15 for the more popular classes—who elect to stay on the waitlist. Upperclassmen and particularly department majors and minors receive priority, and their large numbers often preclude others from enrolling in popular courses. Sixty freshmen "convinced they were going to be majors" were recently bumped from a mid-level microeconomics course more appropriate to upper classes, she says. Demands from older students force younger students, with more time to complete requirements, to wait their turns before enrolling in intermediate and upper-level courses.

"Our administrative assistant does a great job of getting people in who need to be and we're flexible with our caps, so it's very rare that someone doesn't let a senior in who needs the course," says Anderson. Increased course offerings have helped to ease bottlenecks. This year economics will offer 103 sections, up from 89 in 2002-03. "I would love to add sections up the wazoo every time we have a waitlist," she says, "but then we need faculty to teach them and hiring is a slow process."

A STUDENT ODYSSEY

For many students navigating the terrain of course selection—first and alternate choices, college, major and minor requirements, and off-term and study abroad options—is daunting. In a 2006 oped in The Dartmouth, "Oversubscription Odyssey," AlexTonelli '06 described repeated registration frustration. He isolated 16 courses of interest for that winter term but was closed out of 12, spanning four departments. Finding a course in his government major with only 80 students, Tonelli petitioned to enroll and, after "sitting on a windowsill in an African American studies course [due to crowding] switched into a lecture [in the department of Asian and Middle Eastern languages and literatures] that boasted 114 people. It would seem that those claiming government and economics are the only troubled departments haven't tried to take an Arabic course recently," he wrote.

Tonelli now says,"l did major in one of the most popular departments and I did minor in French with no difficulty. But getting courses with popular professors in most departments is difficult."

Plenty of classmates weren't as deliberate or assertive in planning courses, remembers Tonelli, and that compromised their education. "The worst thing was when other students said, 'Screw it, I don't care,' and then just disengaged," he says. "They'd settle for something else, breeze through it, probably do worse than they would in a class they were interested in and then waste that opportunity."

Still, more than 90 percent of seniors surveyed in 2006 by the Colleges office of institutional research (OIR) were satisfied with the overall quality of instruction and class sizes. "I've had difficulty enrolling in classes before the term starts," says Travis Green '08, a self-designed natural and artificial intelligence major who is also Student Assembly president, "but after talking to the professor...magic happens and a spot opens." He admits that sometimes classes "simply can't get any bigger and profs can only squeeze so many people into one room before the class does n't work anymore."

It's not as though students don't have plenty of course choices. In a table provided by OIR of all courses offered between summer 1998 and spring 2007, minor fluctuations appear from year to year and term to term, but overall course offerings have increased, a trend Jim Wright hopes to continue. Summer 2006 had 27 more courses than summer 1998 (up 16 percent), 86 more in fall 2006 than fall 1998 (up 14 percent), 45 more in winter 2007 overwinter 1999 (up 7 percent) and 23 more in spring 2007 over spring 1999 (up 4 percent). During this time the undergraduate student body grew from 4,057 to 4,085, an increase of 0.7 percent.

"We've added more and more small classes and kept the same relative number of large classes," says Folt, who cites the median/ mean enrollments in social sciences courses (history, sociology, anthropology, geography, economics, government, education, and psychological and brain sciences) as 20/27 in 2005-06, compared to 26/34 in 1986-87.

RATIOS AND FACULTY HIRING

Dartmouth's student-to-faculty ratio has improved from 12-to-1 to 8-to-1 in the past decade, the only period for which Dartmouth has data. According to self-reported numbers from other institutions, this places Dartmouth sixth in the Ivy League, better than only Brown and Penn, both at 9-to-1. Student-to-faculty ratios at Princeton, Yale and Harvard are 5-to-1, 6-to-1 and 7-to-1, respectively. Given that Dartmouth, unlike other Ivies, employs teaching assistants (TAs) only in its math department—where they teach only 10 to 15 of the more than 1,500 courses offered by the College—one might assume this positive distinction is the reason Dartmouth lags behind its peer institutions. That is not the case. According to the universal standard for calculating the student-to-faculty ratio, as set forth by U.S. News & World Report, TAs are not counted.

There is, however, another factor at play. The other Ivies have graduate programs in the humanities and social sciences, says Sheila Culbert, outgoing senior assistant to President Wright. As a result they offer more courses and employ more faculty faculty who will also teach undergraduates and count in the undergraduate studentto-faculty ratio analysis. "Our student-to-faculty ratio looks worse than Harvard's, but it could be better if you look just at resources allocated to undergraduates," she says. Other schools count a lot of resources that are there for graduate programs. They should be using FTEs for their undergraduate program, but that's just too complex for U.S.News & World Report," she adds.

Since 2000,43 new tenure-track faculty positions have been added and filled in arts and sciences. If the College has more faculty and a better student-to-faculty ratio than ever before, why then this increase in course oversubscription? The issue is multifaceted.

"The student-to-faculty ratio alone does not allow you to determine if there are class-size problems," explains Trustee Rodgers. "You must look at individual departments. For every department that is fortunate enough to enjoy a student-to-faculty ratio well below the average for the College there is necessarily another department that suffers a student-to-faculty ratio well above it. These imbalances occur because we make lifetime tenure commitments to professors in departments whose enrollment may decline over the years. It is cold comfort to an economics student denied a course that the German department has tiny classes."

Obviously Dartmouth needs more professors. With that in mind, $75 million of the $711 million "academic enterprise" imperative of the current Campaign for the Dartmouth Experience has been earmarked to endowing 25 new positions—five distinguished professorships at $5 million each and 20 professorships at $2.5 million each. In addition, last fall President Wright spoke of simultaneous goals to increase course offerings and increase the percentage of classes with fewer than 20 students to 70 percent of all classes. "I would encourage Dean Folt and her colleagues to work with faculty to determine a strategic plan for growth," he said in his annual report to faculty.

Exactly how the plan will be devised, given the Colleges failure to track enrollment and closeout data uniformly across departments, remains to be seen. There is a critical need for such a strategy as the College prepares to fill those 25 new positions in addition to replacing the 20 to 30 professors each year who retire, relocate or fail to receive tenure or reappointment. Combine those numbers with the Colleges high standards for professors and mix in the length of time necessary to recruit, hire and move these faculty to Hanover and you're looking at a year-long process for each position.

Some faculty openings, such as planned retirements, are predictable. Faculty who are denied reappointment or tenure typically remain on campus for an additional year, giving departments time to search for replacements.

When any faculty position opens department members meet with the associate dean of the faculty to discuss their qualifications for the ideal candidate. The department then begins recruiting, advertising in professional journals and asking faculty to attend meetings and consortia and network with colleagues in the field. Typically, "well over 100 applicants for one position" are considered, says Folt. The departmental hiring committee reviews all applications, settles on a short list and then discusses these candidates with the associate dean.

Select candidates are invited to Hanover to present their work and meet with faculty and students. The deans office negotiates hiring details. For senior-level hires at the associate professor or professor level the Committee Advisory to the President (CAP) evaluates the candidates scholarship and teaching history prior to making an offer. The CAP is composed of the president, dean of the faculty, provost and six faculty members voted in by the entire faculty and representing each division—sciences, social sciences and humanities.

Faculty with tenure at their previous institutions do not automatically receive it at Dartmouth. The CAP evaluates tenure eligibility and makes recommendations that must be approved by Wright and the trustees. New faculty at the junior or assistant professor level have up to six years to teach and research before preparing a tenure packet for review by the CAP.

Filling faculty openings is only half the battle. Hardest of all, says Folt, is predicting raids by other institutions. "We have a great faculty known for their scholarship as well as for their teaching. They are very attractive to other institutions, so what we do here is try to ensure that we have competitive salaries and faculty support programs in place, and we work hard to match outside offers if we need to."

Dartmouth's rural location poses an additional barrier in bringing new faculty to campus. Hanover, says Folt, "can provide dualcareer couples with a bit more of a challenge regarding spousal employment."

When asked whether Dartmouth lags in hiring needed faculty, board of trustees chairman Ed Haldeman '70 responded: We could have improved the [student-to:faculty] ratio even more by being less rigorous. Whatwe are seeking is very special. Avery small minority of professors nationwide are great teachers and do great primary research as well. For sure we want to increase the size of the faculty, but to expand the size of the faculty and risk quality is not a great idea. What we've been trying to do is all these things simultaneously."

MISPLACED PRIORITIES?

Critics of the current College leadership argue that faculty hiring has not been rigorous enough and has been far outpaced by administrative growth. "Even a period of unusually vocal student agitation over class size and course over-enrollment [hasn't been] enough to break the trend we've seen over the last decade of significant growth in the size of the College administration," says trustee Stephen Smith '88. "Over the last 10 years, a period of low inflation, the amount spent on administration has doubled, going from $13,742,000 in 1996 to $30,536,000 last year."

According to the 2006 McKinsey Report executive summary, from 2001 to 2006 Dartmouth filled 111 new administrative and support positions and cut 25. New hires were largely in development (38 FTEs), student life (28.5) and the dean of the faculty's office (14). In its assessment of Dartmouth's administrative functions, management consulting firm McKinsey considered the compound annual budget growth rate of 1.1 percent appropriate to the number of students and similar to growth at peer institutions.

Even so Smith believes these numbers indicate misplaced priorities. "The administration would likely protest that it has expanded the faculty and increased financial aid," he says. "Indeed, it has. My point is that if we didn't waste so much money each year on needless bureaucracy we would have even more money to spend on faculty hiring and financial aid."

College administrators refute this charge and point to the specifics of the hires made in various departments. The 28.5 FTE student life hires comprise newly created positions as well as increased hours for pre-existing positions, says Gordon Taylor, executive officer, dean of the College office. The offices of residential life and student-life hired 14 of them in response to student demand and a greater number of residence halls. Others were added because of NCAA student-athlete and U.S. government requirements and needs in Safety & Security, health services and campus maintenance.

The expansion of Folt's staff by 14 FTEs included the incoming transfer of an office supporting premajor advising, student research opportunities and student fellowships. New hires were added to support faculty research grants in order to comply with new federal mandates and computer support for faculty information technology and teaching needs. A new associate dean also came aboard to support growing international and interdisciplinary academic programs.

In development most of the 38 FTEs hired support the current Campaign for the Dartmouth Experience, which began in 2002. To understand why so many development positions were added, "context is really important," explains Carrie Pelzel,vice president of development. Before the Colleges last major development campaign in 1990 the development office decided to significantly increase staff. Ultimately $568 million was raised, against a goal of $425 million. Annual gift revenue was raised to $l00 million from $50 million, a level sustained since that campaign. "You have to invest money to raise more money and permanently elevate the level of gift support for the institution," says Pelzel, pointing out that the cost to raise a dollar of funds averages between 10 and 12 cents. The current campaign's goal is $1.3 billion and a doubling of annual gift revenue.

Several of these new development positions were intended to be short-term and downsized after the campaign ends in 2009. However, according to Pelzel, it is "not clear how many will be terminated. This is a revenue-producing enterprise. Even though you invest more in people, you end up raising hundreds of millions more for facilities, endowments and, we hope, permanently raise the level of gift support." The president, provost, executive vice president of finance and administration and Pelzel will look at institutional demands and fundraising goals before deciding whether or not to slim down her office.

WHAT LIES AHEAD

Ironically, as Dartmouth grapples with how to ensure a higher percentage of small classes, many of its peer institutions, as detailed in a December New York Times story, are talking about expanding their student bodies to offer exceptional learning opportunities to qualified students now being turned away for lack of space.

Current Dartmouth strategies—from escalating faculty hiring, counseling students to better plan course selection and their majors, and more closely tracking closeouts—are focused on restoring Dartmouth's tradition of small classes that accommodate all students who want them, but it is not entirely clear how the College will get there.

There will always be some professors, courses and time slots more popular than others. There will always be a certain number of closeouts, and no one wants faculty burnt out from teaching too many sections. But class size and oversubscription remain, for Haldeman, "an acute problem we need to continue working on."

"I would love to add sections then we need faculty

Critics of the current College leadership argue that faculty hiring has not been rigorous enough and has been far outpaced by administrative growth,

LAUREN ZERANSKI is a frequent contributor to DAM. She lives inNewton Center, Massachusetts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Spoil Sport

March | April 2008 By Brad Parks '96 -

Feature

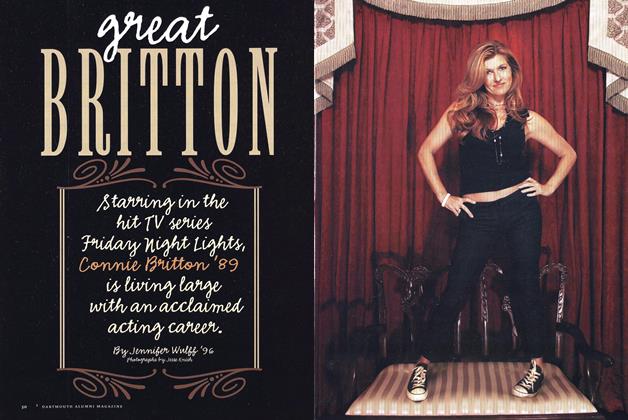

FeatureGreat Britton

March | April 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Interview

Interview“The Timing is Right”

March | April 2008 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONDesigner Genes

March | April 2008 By Ronald M. Green -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLiving Room Learning

March | April 2008 By Jane Varner Malhotra '90 -

HISTORY

HISTORYDéjà Vu All Over Again

March | April 2008 By Marilyn Tobias

LAUREN ZERANSKI ’02

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Future as Past

June 1980 -

Feature

FeatureA VETERAN MOVES ON

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1970

JULY 1970 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureDid Webster Really Say It?

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureTHE UNSUNG HERO OF THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE

FEBRUARY 1969 By Susan Liddicoat