THOUGH our older American colleges were modelled at their foundation on the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, they have in these latter years moved very far from the English universities in the matter of undergraduate instruction. This has been due partly to necessary adaptation to changed conditions, partly to Continental influences, and in a measure to a somewhat purposeless drift in educational matters. All of us have glibly subscribed to the dictum that Mark Hopkins and a log are the essential factors in the ideal college, but only here and there has a voice, proclaimed that we were getting as far as possible from that ideal. Meanwhile, granting that Mark Hopkins were legion in these days, we should have him pretty well separated from the student at the other end of the log by walls of brick and stone. Besides, the dictum is faulty in that it implies a passively receptive pupil. It says nothing of his tools and his labor.

Yet the time seems to have come when we are again to emphasize books and the man in their relation to the individual student. That, I take it, is what makes the experiment undertaken this present academic year at Princeton peculiarly interesting and significant. Though harking back to older ideals the movement is not reactionary ; though taking a leaf out of English experience it is not imitative ; it is rather an effort to emphasize the two educational factors which have been most neglected in our colleges hitherto.

The student has been so occupied in hearing lectures and in getting up subjects for recitation, when employed with intellectual work at all, that he has had little time for the serious business of study. The " reading man," as known in the English universities, has not indeed been altogether unknown, but he has been somewhat of a phenomenon. Plenty of men have taken a high stand at graduation without having the least notion that they might reasonably be expected as educated gentlemen to know how to grapple with a subject for themselves. An effort to make the individual student feel a sense of responsibility for his own intellectual salvation, read recommended books for himself, and consider his course as something more than passing examinations in a certain number of hours' work per year, is one of the two main purposes of the Princeton system. The second is closely related to this. It contemplates the utility of establishing personal c onnections between faculty and students. Obviously, the undergraduate is not capable of carrying on independent studies without direction, encouragement, or external spur. Just as obviously, he can best be aided by some older man of scholarly training, who has studied his inclinations and deficiencies and who has earned his confidence. To accomplish this, the association must be regular, informal, and intimate. Teacher and student should be as far as possible comrades in study.

Most Americans who have observed the inner workings of Oxford or Cambridge would agree, I suppose, that the English system, at least for undergraduates who are trying for honors, is strong at precisely the points where our American instruction has been weakest. To President Woodrow Wilson, long before he was made the head of Princeton University, came the thought of remedying American defects by the infusion of English excellencies. His energy and enthusiasm have made possible a trial of the plan on a scale commensurate with its importance. We shall thus soon be able to judge its practicability by the results which it accomplishes, though there should be no haste to bring in a verdict against the scheme if it does not immediately bring to pass all the reforms that could be desired. We must recognize the common human frailty of both teachers and students, as well as the difficulty in at once solving the many problems of detail which naturally arise. To the possibly biased view of one actually engaged in the work, however, it appears that the plan is working admirably after only a half year's trial.

The Princeton system is not based, it will be observed, in any sense on a wholesale borrowing of English methods. All the essentials of the American college — an institution unique in the educational world - are preserved unaltered, while certain seemingly useful features have been Shafted from an older stock ; or, if you choose to look at the matter historically , these elements have simply been restored to an importance which they once enjoyed, at least theoretically. The general scheme involves the constant association of every member of the faculty with a larger or smaller number of undergraduates as individuals. Over their studies in his department and over their general progress, as far as practicable, each teacher will exercise constant supervision. He will do his best to act as their counsellor and friend, not as a matter of routine, but of personal interest. He will teach them, as far as he can, to have thoughts and opinions of their own, to base their judgments on proper grounds, and to express their knowledge and convictions intelligently.

The reader will see that this individual intercommunication necessarily takes a great deal of time, that it is even extravagant from a commercial point of view. The proper economical way, of course, is to throw instruction broadcast in a large lecture hall and to trust whatever good angels youth may have to help the student seize and correlate the crumbs of knowledge as they fall. But commercial economy is often intellectual extravagance. If the desired results are attained, Princeton will be justified in adding to her faculty by fifty per cent (about fifty men all told) in a single year. Most of these gentlemen give the greater part of their time to the task of individual conference. They are, in short, those preceptors whose collective title has given the system its popular name. The title is confessedly a makeshift, born of a desire at once to indicate their peculiar office and to avoid the connotations which the word tutor has acquired in this country. They are for the most part men in whom the enthusiasm of youth is not altogether dead, who have, however, had from four to eight years' experience in teaching, men presumably of some cultivation and considerable scholarly equipment. They have the rank and salary of assistant professors, and they are therefore sufficiently worshipful members of the university circle.

Of course, the ordinary routine of lectures and recitations must still go on, since some subjects and certain aspects of every subject can best be taught in these more formal ways. To this work the full professors and the comparatively small number of assistant professors, aided by a corps of instructors and assistants, devote the greater part of their time. Lectures, according to the theory, are designed for the general guidance of the student rather than for his instruction in matters of specific knowledge. They are intended to explore the subject which he himself is studying, to point out its divisions and its relations to other branches — in short, to lead and inspire the undergraduate in his chosen path. The professors are also the examining and grading board, each one concerning himself with the courses under his direct charge and acting with the advice of the preceptors who may be connected therewith. Every professor also does preceptorial work in his own courses, usually with men from other departments who may be electing work in his.

The preceptor, meanwhile, takes part in all the strictly undergraduate courses of the department. He may have students in six courses in the same term, so that his activity is not limited to any one field. He must be at home, or must make himself conversant, with every subject which is likely to come up in the curriculum of the department — an ideal somewhat difficult of attainment. At the same time, he will not be so sorely tempted to pose as omniscient as is the man behind the classroom desk. If he is at all wise, he will rather act the part of a fellow disciple of his pupils, relying upon the methods learned in regions which he has particularly studied to guide his little band of students through lands hitherto known to him only as to the casual traveller. He will not cultivate his chosen fields of thought less assiduously, we hope, because of these excursions. Indeed, he will be aided in the concentration 'necessary for productive scholarship by the fact that in many cases he is giving a graduate course or some course for selected seniors on his own account. He must, it seems to me, stand guard very earnestly against mental dissipation, for that way lies danger both to himself and, in the long run, to his students.

In any given course the professorial lecturer and the preceptors form a little council. Under the chairmanship of the professor they meet at more or less frequent intervals to discuss matters of common concern, such as the general scope of the course, the division of time between various parts, and the amount of reading to be required. Each man has a voice in the settlement of such questions and usually has very definite opinions to offer. After the semi-annual examinations the same body becomes a court of judgment on the paper which has been set by the professor and the grades which have been given the students. The jurisdiction of this council is not extended, however, to matters of detail. When plans are once laid, the lecturer and the preceptors are left equally free to do their work according to their own inclinations.

The actual working methods of the system at Princeton may perhaps best be illustrated by looking first at a preceptor's relations to the courses in a single department, and secondly at a student's relations to the courses which he follows in the several departments of his choice. For convenience, I will discuss the first point with reference chiefly to the instruction in English, with which I happen to be most familiar. Considerable latitude has been given each department with reference to detail, so that a good many statements which may be exactly true of one subject may be in a measure false of another ; yet the general conduct of courses is everywhere similar.

Possibly the most sweeping reform with reference to the study of English, which the new system has introduced, is the abolition of courses in rhetoric and composition. The growing belief that the prime requisite of. good expression is having something to say has led to this step. The student is to be required to write in all courses, or in almost all, not only in the department of English, moreover, but wherever he will be aided in the definition and correlation of knowledge by the process of expression. He will be taught to formulate his ideas clearly, and he will not be allowed to go on with his work till he has succeeded in doing so. Thus no one department will shoulder alone the responsibility of teaching an inarticuate freshman to express his ideas as he acquires them, but all his preceptors will be actively interested in his progress. The student will not be asked to write beautifully about nothing at all, but plainly and logically about something that he has learned.

The preceptor in English, according to present arrangements, meets men of all four classes. He gets acquainted with a group of freshmen and lays his plans to follow them through their course, in so far as they take work in the department. He divides them into little groups of from three to six men, or in some cases instructs. them . individually, and arranges convenient hours for them to meet him each week, usually in his study. He tells them what to read, after considering their tastes and needs, discusses the books with them, and carefully corrects the written reports which they make. In the case of upper classmen, especially, he finds that a wide latitude of method is necessary to get the best results in various courses treating language or literature. Frequently he discovers at the end of an hour that he has been discoursing on some subject which has proved to be in need of ordered exposition ; at other times he uses Socratic questioning; sometimes he finds it necessary merely to direct an impromptu debate; or again he reads with his students from the works of the author under discussion.

In the course of a week the preceptor devotes between twelve and fifteen hours to such stated meetings, though he finds that students are very likely to drop in at other times for advice or suggestion. On this account twelve regular hours weekly are enough for him to undertake, and anything beyond that number should be regarded as merely a temporary defect. As a rule the preceptor restricts his conferences to the morning hours of the four middle days of the week, though he sometimes devotes part of one or two evenings to these exercises. Thus he meets all his charges at least once a week and tries to keep informed as to their mental health. He soon comes to know his students so well that he can detect any marked change in their attitude towards their work, and he could without difficulty foil most attempts at " bluffing " or outright dishonesty. But, as an undergraduate remarked, " that sort of thing won't go when you meet a man in his study." Indeed, this personal association of gentleman with gentleman is the best guarantee of honest work that could be devised. The feeling for integrity of character which has made the honor system in examinations possible at Princeton and elsewhere must eventually extend its sway over academic life as a whole. In the furtherance of this reform the preceptor is certain to be an important agent. By the time he has followed his students through four years of college work he will either have won their entire confidence or merited their contempt - at all events he will know as he is known. The traditional barriers will have disappeared, and with them most occasion for dishonest practice.

From the student's point of view the preceptorial system doubtless appears in a rather different light from that in which it is held by the instructor. At the end of the first half year of its existence it probably seems to many an ingenious plan for the promotion of hard work. "All through my course," said a senior to the present writer, " I had been looking forward to this year with the thought that I should have next to nothing to do, and here I am sweating away as I never have done before." " Anyhow," remarked another in exculpation of some deficiency, " all of us are working three times as hard as we used to" Allowing for the enthusiasm of defense, it is safe to say that the average number of hours of work per week on the part of the Princeton undergraduate has been measurably increased ; and the result could scarcely fail to be the same wherever the system might be introduced.

Let us take the case of an upper classman and consider the plan of his work with reference to departments and instructors. He has elected, let us say, the department of history. He may perhaps be taking three courses in history and political science, one in English literature, and one in some modern language, with a schedule amounting to fifteen hours a week, three hours for each course. Two hours out of every three scheduled he devotes to lectures or recitations, the third to a preceptorial conference. Thus each week he has five hours of work with his preceptors, and with three different preceptors. To the historian he will be peculiarly responsible, since he is presumed to be more interested in the department that he has elected than in any other. He may with propriety be asked to give extra time in the preparation of reports in his chosen subjects, for he is considered as actually a member of the department in question. In years to come, or we may hope so, he will be so well acquainted with his departmental preceptor that no friction will arise through misapprehension or misapplication.

In every case the preceptor arranges for an hour of conference with the individual student according to their common convenience. The student is thereafter expected to attend at the appointed place of meeting each week, but he is not marked as absent if he does not come. It is part of the plan to encourage individual responsibility that he be left free to come or not according to his inclination, or at least without compulsion from the central university offices. The matter must be settled between his preceptor and himself. He knows that he may be debarred from taking the final examination if he does not attend to his work properly, and that his preceptor's report will be of considerable weight in making up his semi-annual grade. With that in mind he may be left to such discretion as his experience suggests. Indications thus far make it appear that he is capable of carrying on his studies in this independent way, provided he has competent direction.

It is on part of the preceptorial system to reduce good students and weak ones to a common level. Indeed, the cultivation of personal relations with his instructors and the habit of working for himself are likely to prove powerful incentives to the bright man. He will see more reason for working if he can be made to look at his courses as subjects of living interest rather than mere tasks. The dull student, on the other hand, will have the help of personal direction, will be able to learn what he probably never has learned,—how to study. The preceptors are in no sense of the word coaches, though all admit that it will be necessary to fight against the temptation in that direction. Yet much legitimate help can be given students, both the dull and the brilliant, in the way of stimulating and directing their endeavors. On the whole, the bright man is likely to Have rather better opportunities than heretofore for intellectual expansion, while the level of mediocrity will probably be somewhat raised.

Not all courses and not all departments have as yet been brought under the preceptorial system at Princeton. One treatment does not serve for every subject. The natural sciences everywhere, with their laboratories and organized experimental work, have long had the equivalent, at least theoretically, of the methods just applied to the humanities. For them probably no change of plan would be advisable. Elementary courses in the languages also fail to follow the general scheme to the fullest extent, since the work of the conferences does not differ essentially from that of the recitations, merely emphasizing conversation, composition, or rapid reading. There are at present a good many anomalies, indeed, which experience must help to straighten out. There is, moreover, no tendency to worship any undeviating theory, or at least the fetich, if adored, is recognized as being not without stain.

Yet a half year's trial has persuaded most observers, I think, that the plan conceived by President Wilson and enthusiastically adopted by Princeton, is a sign of excellent omen for the collegiate work of America I for one am convinced that it has come to stay and that it is likely to solve the problem of undergraduate instruction in our larger institutions. The day for a final judgment has not yet come, but the future of the system is most promising. Already the Princeton undergraduate has invented the verb " precept" and the substantive " preceptee "as a part of his vocabulary, which shows perhaps better than could be done by formal statement how naturally he has entered into the spirit of the endeavor. We may hope that he speaks with an insight prophetic of the future of collegiate instruction. The principle of really independent study under suitable direction is one which might be extended to good purpose, moreover, in the work of our graduate schools. Less inelastic machinery and more close contact with books and men are the great needs of our higher institutions of learning.

Gordon Hall Gerould, '99, Preceptor at Princeton University

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ADMINISTRATION OF THE MODERN COLLEGE*

February 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE practical workings of the preceptorial system

February 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE RHODES SCHOLARSHIPS

February 1906 By Julius Arthur Brown '02 -

Article

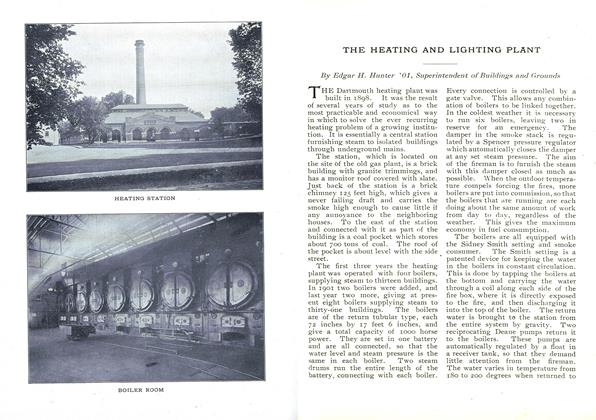

ArticleTHE HEATING AND LIGHTING PLANT

February 1906 By Edgar H. Hunter '01 -

Class Notes

Class NotesSECOND ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES.

February 1906 -

Article

ArticleWASHINGTON'S BIRTHDAY EXERCISES

February 1906

Article

-

Article

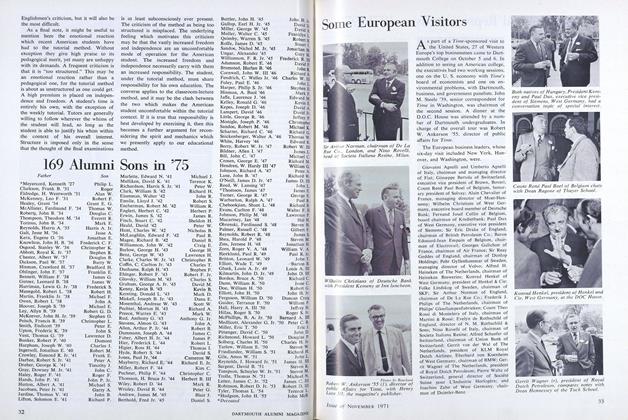

Article169 Alumni Sons in '75

NOVEMBER 1971 -

Article

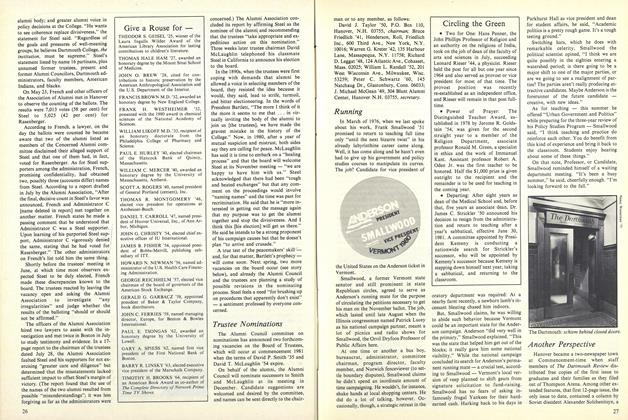

ArticleGive a Rouse for

September 1980 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

NOVEMBER 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Ambulance

January 1941 By Lloyd K. Neidlinger, Max A. Norton -

Article

ArticleGreece in the Centennial Year

January, 1931 By Professor Charles D. Adams -

Article

ArticleA DECADE OF RENEGING

February 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40