"A culture without art can hardly he called a culture at all."

President Dickey frequently referred to Dartmouth's educational mission not as "the liberal arts" but as the "liberating arts." "The liberal arts become the liberating arts," he explained, "when taught, learned, and practiced—as they were created—as the witness of a man by personal struggle pressing toward his richest, earthly destiny. The liberal arts are the product of the straggle, man by man, for the liberation of man's mind and spirit."

President Dickey's confidence in the liberating quality of the liberal arts was based upon his conviction, first, that "as the chromosomes of civilization, the liberal arts bring the best of the past to the service of the present; and, second, that...they liberate the best in a man into an expanding future." I would argue that the fine arts engage us even as they enable us to liberate the best that is within us, and thereby transcend ourselves.

Such transcendence is what an artist achieves when the creative and expressive process becomes so all Transcendence is what a Dartmouth student described when she said: "Art is about control, but it is also about letting go of control. You need to have disciplineto get into the studio, to learn from your teachers, to look at the masters, and to decide what you like and don't like. But, ultimately, you need to let go." It is in the act of letting go that the possibility of transcendence arises, and the artist breaks through to a more rarefied level of creative achievement.

Artists—whether they be performing artists like those celebrated in the Hop, visual artists like those exhibited in the Hood, or writers like those whose works one finds in Baker Library—transcend themselves in still another way. Their efforts—original though they are—make them a part of the tradition in their field.

Artists inherit a legacy—often an intimidating one. In attempting to be worthy of that legacy, they often experience what the critic Harold Bloom has called "the anxiety of influence." Nevertheless, when artists see themselves as part of a continuing traditionfound sense of inspiration and empowerment. In joining and extending that tradition, they become a part of something far larger and more noble than them- selves. Similarly, when drama devotees attend the theater, they participate in a process of performance that is at once timeless and contemporary, at once profoundly personal and deeply communal.

Artists transcend the self in still another way, and that is in the sharing of their work with others. The arts are, above all, an expression and a communication of aesthetic delight. I was deeply moved to see a photograph, almost two years ago, of the conductor Zubin Mehta, the tenor Jose Carreras, and an Italian opera company getting off a plane in Sarajevo wearing flak jackets and helmets. In the burned-out ruins of Sarajevo's National Library, Mehta conducted Sarajevo's orchestra and chorus in a performance of Mozart's Requiem, his Mass for the dead. As Mr. Mehta said at an open rehearsal, "We have come for you to bless us more than we to bless you. And he hoped for the day when they might return to play Mahler's Second Symphony, TheResurrection.

The arts enable persons to speak out, "to resist," as Mehta did in Sarajevo, as Athol Fugard did in South Africa, as Ariel Doifman did in Chile, as Ibsen did in Norway, as the Maly Drama Theater did in Soviet Russia. In those cases, the transcendence of the self—the liberation of the self—is nothing short of heroic. The world that the playwright creates on stage reminds us, implicitly or explicitly, that our world need not always be the way it is.

The arts remain one of our surest means to uplift the spirit, to enlighten the soul, and to school the heart and mind. Even as we seek to minister to society's material needs, we must forever recognize that the fullness of human potential can be realized only if we appreciate the fullness of human accomplishment. We must forever remember that a culture without art can hardly be called a culture at all.

That is why it is essential that a liberal education fully embrace the visual and performing arts. That is why the Hopkins Center and the Hood Museum play such an essential role in Dartmouth s commonwealth of liberal learning. And that is why I am pleased that the College's new degree requirements ensure that a student does not graduate from Dartmouth without experiencing the arts in some significant way. For to see the world as artists see it is to live more humanely and more generously.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWha is There to Teach About Art?

May 1996 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

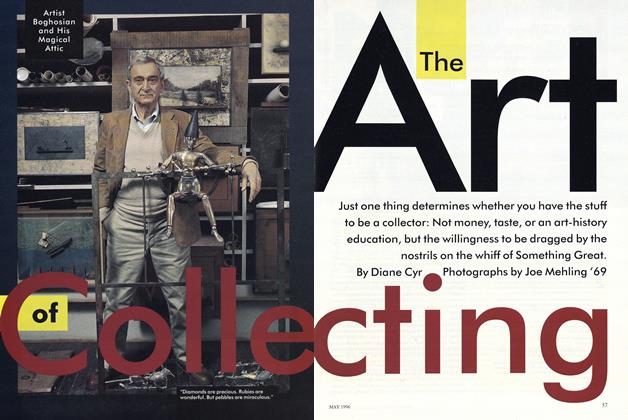

FeatureThe Art of Collecting

May 1996 By Diane Cyr -

Feature

FeatureA Mini-Seminar On Two Hood Pieces

May 1996 -

Feature

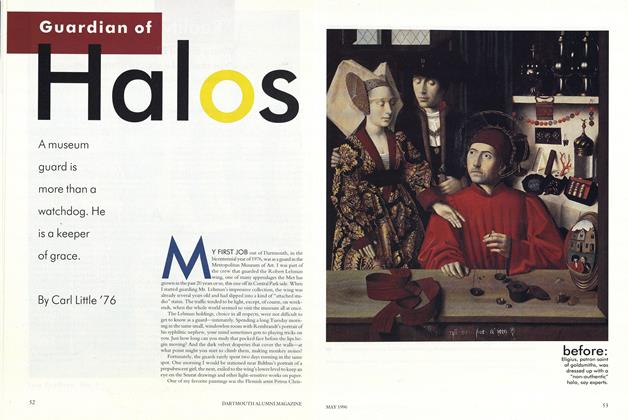

FeatureGuardian of Halos

May 1996 By Carl Little '76 -

Feature

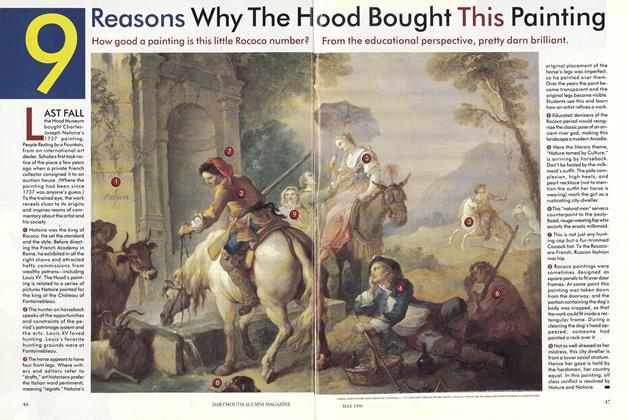

Feature9 Reasons Why the Hood Bought This Painting

May 1996 -

Article

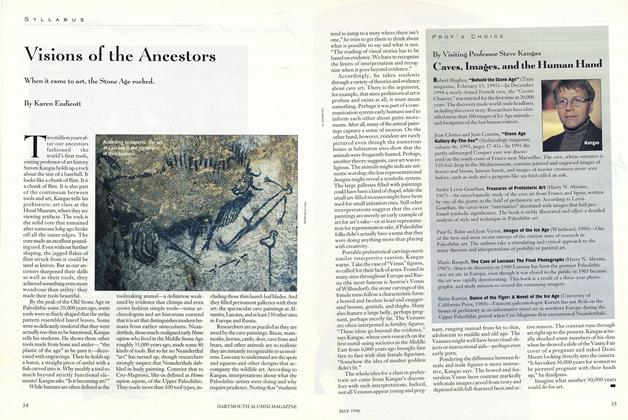

ArticleVisions of the Ancestors

May 1996 By Karen Endicott

James O. Freedman

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorPresents Accounted For

June 1994 -

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIs "The College" a College?

December 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTHE PASSIONS OF SCIENCE

December 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleMY HEROES

MARCH 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Lifelong Pursuit of Education

Winter 1993 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleIndustry Specialists Needed

December 1941 -

Article

ArticleAnother Jungle Journey

MARCH 1959 -

Article

ArticleOff to a Good Start.

DECEMBER 1982 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Article

ArticleSki Team Outlook Good, If There's Any Snow

January 1951 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleMaynard Wheeler '61 Offers "Vision of Hope" to Peruvians

June • 1985 By David Wank -

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN REPORT

APRIL 1970 By JACK DEGANGE