Under the title, "Dartmouth's Courage of Tolerance," the Springfield Morning Union of November 14, published an editorial on the policy of Dartmouth administrative officials in allowing within the college the presentment of points of view not held in general by majority opinion. The Union said:

"With a liberality uncommon in collegiate circles President Hopkins of Dartmouth has declined to oppose William Z. Foster's speaking before a body of students acting under their own auspices. This decision for tolerance is based not only upon his faith in the ultimately triumphant common sense of his undergraduates but upon the belief that intolerance defeats its own objects. It is a fact not well enough appreciated in dealing with such matters that undergraduates tend to become radical under exclusively conventional instruction and, conversely, there is very little doubt that if the student were brought into contact with nothing but radical teachings he would tend to become the most aloof and unyielding of reactionaries.

"When a young man reaches college he seems somehow to shake off the imitative sense that has ruled him thus far and to adopt in its stead a very considerable sense of critical opposition. He is no longer the sedulous ape to both the faults and virtues of his teacher. On the contrary, though he may accept the teacher's views in theory and set them aside for future adoption, in practise he is very strongly inclined to follow his own opinions, which for more or less palpable reasons are usually the direct antitheses of those he mainly receives in the classroom.

"Again, despite the very considerable accumulation of opinions and evidence to the contrary, the undergraduate is habitually the possessor of a very good fund of common sense. For all the fuss that has been made over him, he is really able to swallow very strong doses of radical and unbalanced opinions without being very seriously affected thereby, unless—and here the trouble arises— unless the radical, himself is opposed and punished. Then things take on an altogether different aspect. Once the radical has been stamped with the cachet of "martyr he will sweep all but the most astute of the student body before him. Whether it is the familiar question of the underdog, or of the college man's love of fair play, and dislike of intolerance, it is hard to determine, but the fact remains that he is the exceptional undergraduate who can remain impartial once the radical has been in any way molested or suppressed.

"There is little reason why the undergraduate should be prevented from coming into contact with even the most extreme views. He may be captured by their novelty at first, but if more conventional ideas are sounder it will take him no great length of time to discover the fact and to cast aside the hocus-pocus which he had erstwhile favored. On the other hand, any conclusion which he does not arrive at himself, by his own independent reasoning, is a conclusion very apt to be undermined by the first clever sophist who appears.

"Finally, the intelligent and tolerant man is very loath to suppress men simply because their convictions do not accord with his. Even the most fanatical views are sometimes based upon enough of truth to make them decidedly worth hearing. The fanatic and the opinionated theorist are often our best destructive critics, and it is well to bear in mind that without good big inoculations of criticism a man or a nation may become self-complacent, smug and stagnant."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

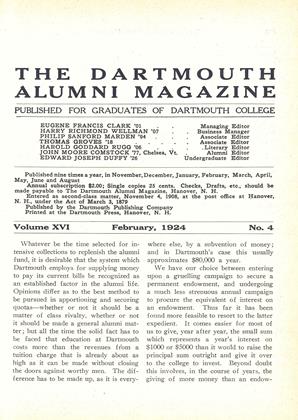

ArticleWhatever be the time selected

February 1924 -

Article

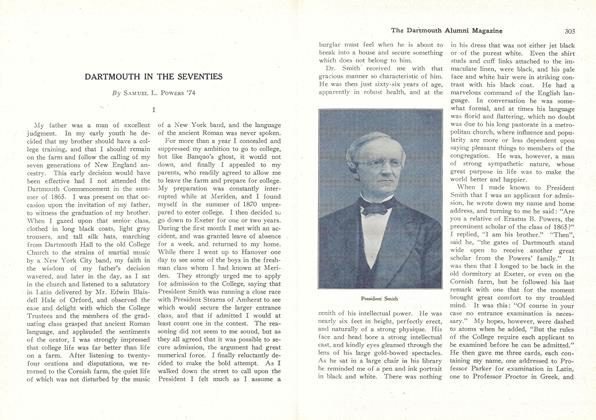

ArticleDARTMOUTH IN THE SEVENTIES

February 1924 By Samuel L. Powers '74 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH JOTTINGS OF A SOMEWHAT DESULTORY READER

February 1924 By Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Class Notes

Class Notes$1000 REWARD PEARL NECKLACE

February 1924 -

Article

ArticleHARRY HARMON BLUNT

February 1924 By Thomas Dreier -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1924