I cannot sing the old songs I sang long years ago, For heart and voice wpuld fail me,

And foolish tears would flow.

Not my foolish tears would flow; but others'.

Sixty years ago the songs of the colleges were many. H. R. Waite of Hamilton College collected more than three hundred, and published them in his Cartnina Collegensia in the hope that "their happy influence may remain When for us the song be ended. And the singer is no more."

Of those that were peculiarly college songs few are now sung, or even known, by the modern collegian. They were of their day; but the best that can be said of their successors is that they, also are of their day. The backs go terring (yes, I mean terring) by, Williams true to purple, Amherst, brave Amherst, Thy honor shall be ever dear, Old Dartmouth Green without a peer, s-erve their present purpose. Fashions will change. The historic association and the fortissimo chorus will doubtless preserve the five hundred gallons of New England Rum to a time when the remote generation of undergraduates will inquire what is meant by rum. Richard Hovey was not a physiological chemist; and one admirer of his poems could wish that he had said stiff-legged and boneheaded in plain language rather than boast of the granite of New Hampshire in their muscles and their brains.

Singing merely as a joyful exercise is less popular than in the middle of the last century. It has gradually gone out, because there are more diversions and because of the tendency towards the highly trained and the professional. There are football songs, fraternity songs, glee club songs, comic opera songs, songs by grouped classes, all occasional and sometimes forced; but getting together and just singing, sincerely, ingenuously, and raucously is what the man said in town meeting of the grade over the "mounting", "a leetle scurce."

It is not so much the contrast of the present and the past that interests us now as the characteristics of this earlier period of song.

The barbarism of many of these old songs is startling, and attractive to us human beings who are as superficially civilized as the red-jacketed monkey of the organ grinder. They abound in meaningless mouth-filling sounds belonging to a period when ideas had not been associated with vocal noises. Perhaps they had their inspiration from the animalism of the Barbary Coast, or are inherited from those who were held in contempt because they did not speak the Greek language, the barbaroi. Consider a few specimens.

In introducing some metrical remarks about Boston City where all the girls they are so pretty, of the following tenor or bass, Shool, shool-i-rool, shool-i-shagarack, shool-a-barb-a-cool. The first time I saw psilly bally eel, Dis cum bibble lolly boo, slow reel, the indulgent editor explains "that the words have some of the classic quality of the immortal. Mother Goose, when the student feels that he has been wise long enough and is determined to let up and be foolish for a while just for the variety of the thing." So that is it,—a relief from being wise. With this idea in mind it is evident that whoever bursts forth with co-ca che-lunk-che-laly, hi-ho-chick-a-che-lunk-che-lay distinctly declines to tell any one in mournful numbers that life is but an empty dream; and the refrain upidee, upida upidee-ida gives hope that the surly youth who bo.re mid snow and ice The banner with the strange device, did not miserably freeze to death after he might have done so much warmer and better. B-a-ba, b-e- be, b-i-bi, ba-be-bi, B-o-bo, ba-be-bi-bo, b-u-bu, ba-be-bi-bo-bu comes to us from this far past as tender and moving as going up stairs and gently bumping down again. And there was and is plenty of time in college to go through with every consonant in the alphabet and have much fun with the c's and the g's. Swee-de-le-wee-dum-bum is surely the fife and drum of the old New England Training Day, and Swee-de-le-wee-chu-hi-ra-sa introduces the devilish instrument which after three lessons makes you the life of the party.

Who can blame the fres'hman whom examinations have made'pale for consoling himself with the mouth-filling fol-de-rol de rol-rol-rol, adding eel-i-eel-i-eel as a veiled and delicate tribute to Elihu Yale. And is there any more fitting compliment to a girl described as a fine girl and a charmer than fol-de-riddle-ido, fol-de-riddle-oh? Bingo hits something with a good Yankee bang, even an old rooster purchased for fifty cents. But. ju-vallera, ju-vallera, ju valle- valle-valla-ra ought to have a revenue stamp upon it and be marked im-ported with the ictus on the im; no person born on American soil could have invented that slogan. One can' easily imagine Holmes' young oysterman inspired by the fisherman's daughter that was so straight and slim breaking forth With a rook-che-took-che-took- che-took-che, Whack fol-101-diddle-101-a-day; that is what he would say. And the gallant young sophomore must have heard him and let out a competitive With a whack row a fiddle dee dee and a whack row dow row dow.

The maidens always did inspire to nonsense (before girls' colleges were numerous), so As I was walking down the Sitreet and a pretty girl I chanced to meet, why shouldn't I after a few introductory heigho's exclaim Rig-a-jig-jig and away we go three times and follow up with eleven heigho's? Vi-vallavalla-ralla-ra, we brand at once as im-ported and pass on.

In China there lived a little man, His name it was Chingery-ri-chan-chan; His feet were large and his head was small, And this little man had no brains at all. Chingery-rico-rico-day, Ekel-tekel. Happy man! Ruan-a-desgo-canty-o, Gallopy-wallopy-china-go. A confused and unworthy refrain, but illustrative of rattling vacuity.

There are doubtless plenty who would be willing to .warble to the tune of Villikins and his Dinah this requiem to one Loomis who wrote a big treatise on angles and lines with chapters on spheres surveying and sines,

Sing tangent, cotangent, cosecant, cosine, Sing tangent, cotangent, cosecant, cosine, Sing tangent, cotangent, cosecant, cosine, Sing tangent, cotangent, cosecant, cosine,.

These words are well adapted to song and it may be that they have meaning; certainly as much meaning as tooral-i- ooral-i-ooral-i-ay in memory of that unhappy couple of lovers, Villikins and his Dinah.

It shocks one to read from the early days of Beloit,

From evening late till morning free I'll drink my glass crambambuli, Cram-bim-bam-bam-bu-li, Crambambuli

Crambambuli was something awful. There is a legend that it was blazingrum; and rum must be very strong to blaze.

But what can equal the horror, the tooth-gnashing, fire-encircling, jazz-dancing, bone-grabbing horror of Woman pudding and baby sauce, Little boy pie for a second course,- He swallowed them all without any remorse, The King of the Cannibal Islands. Hokee, pokee, winkee wung Polly makee komoling kung, Hangary, kangery, ching-a-ling-ching The King of the Cannibal Islands.

The source of this love of uncouth and meaningless sounds of the mouth must be sought in the deepest twisted fibres of humanity. Gou gah, chu-chu, eeny meeny miny mo, kaf ousa-lum: ta-ra-ra- ra boum-de-ay. Sing polly wolly doodle all the day, bou-lah, calloo callay, O frabjous day, glory, glory, hallelujah (usually without meaning to the singer) show the need of all classes to break out into vocal noise. Can it be due to the practice of rhythmic and mouth-filling sounds on the way up to articulate speech!

Another closely related characteristic of many of these lyrics is the babbling of vain repetitions. Empty words have been taken as signs of empty minds, but perhaps in this instance they are only signs of temporarily emptied minds. Or, as in the case of fugues and so many anthems and oratorios, they indicate not so much paucity of fresh words as superabundance of music with no place in which to put it.

So say we all of us, So say we all of us, So say we all. So say we all of us, So say we all of us, So say we all.

illustrates well the need of room for the music.

But why any youth with a leg with which to run or to kick a football should nine times request in the tune of Greenville to have it sawed off, ending with an imperative and fortissimo "short", needs further study of adolescence. The fugue to the good old tune of Antioch in which the bass chases the other parts and the other parts chase the bass to tell how thoroughly the wondrous wise man in our town scratched and scratched and scratched out both his eyes has in its time made many young persons merry, though perhaps detracting somewhat from the devotional solemnity of Joy to the world the Lord has come.

It's a way we have at Old Si wash (or any other institution of learning) four times, To drive dull care away three times; Mary had a little lamb, little lamb, little lamb: Drink it down, drink it down, drink it down, down, down: Balm of Gilead, Gilead, balm of Gilead, Gilead are more of numerous instances. It seems hardly worth while to relate three times that Old Noah after building his ark drove the animiles in two by two, before specifying the elephant and the kangaroo, or at the last of thirteen similar stanzas to insist thrice upon a permanent position of the nose upon the face for no more substantial reason than that it don't look well out of place.

But now I am a man, But now I am a man, For once I was a sophomore, But now I am a man.

may be no more than a proper balance.

A rapid glance over the pages of this interesting book discloses sentiment and folk lore and fun of a simple day that is gone. Fair Harvard remains with us, and in its pleasantly sentimental setting is most suitable for mellow but not boisterous reunions, after the unfamiliar listener has shaken off the impression that he is hearing Moore's Believe me if all those endearing young charms. And in its company is Drink to me only with thine eyes, not a latter day song of abstention as might be supposed, but Ben Jonson's "immortally careless rapture" of a different and slightly more lasting intoxication than that of wine. Good old Integer Vitae and Gaudeamus Igitur are followed by Lauriger Horatius and many rhyming Latin verses and even Greek which belong to the dear dead days beyond a modern undergraduate's recall.

And there is the rythmic music of Maid of Athens,

By those tresses unconfined, Wooed by each Augean wind

(as once sung at Norwich depot while waiting for a vacation train by sophomore Lomarx of 1872. This joke is only for those whose knowledge of classical mythology runs to the seven labors of Hercules.)

By those tresses unconfined, Wooed by each wind, By those lids whose jetty fringe Kiss thy soft cheeks blooming tinge: By those wild eyes like the roe

Pretty words they were then; probably are now.

One Gladden, '59, contributed at least four songs to the Williams collection, among them a chorus, Ho, boys ho! Merry are we, ho, ho, and this stanza which it is difficult to forgive,

But now we're going home at last To the girls we left behind. And our work will be "eliptical" (a liptickle) But of quite another kind.

(Italics and parenthesis are in the original.) And this same Gladden later wrote the beautiful hym,

O, Master let me walk with thee—

The songs collected by Harry Smith, '69, as peculiarly those of Dartmouth are a barren lot, and I think that those who were in college at about that time would testify that only few of them were ever sung, but fortunately there was no royalty required for singing the other two hundred and ninety or So. Dr. Holmes' Young Oysterman may have been written while he was professor of Anatomy and Physiology here, 1838-1840. but lacks appropriateness unless there is affirmative answer to another old song,—Did you ever see an oyster walk up stairs? This region has never offered great opportunity to a practicing oysterman. But there is charm in the verse. Her hair drooped 'round her pallid cheeks like seaweed 'round a clam, and it gives opportunity for comparison with Byron's treatment of the tresses unconfined.

The author of I'm dreaming now of Hadley, South Hadley, South Hadley, had evidently been listening to the mocking bird. Inevitably one wonders whether the direction of dreams at Amherst has moved to the north in these later years.

That Gymnasium Song with its refrain,

Marching along with shouting and song; March of the muscle and march of the mind; The age is awaking though tradition is strong We've sifted the past and we've left it behind.

marks an, epoch; for Amherst was a pioneer in the required drill of the college gymnasium.

And from far out in the middle west comes the happy relief from Rosalie the Prairie Flower. One may well have doubts about Rosalie;

Fair as a lily, joyous and free, Queen of the prairie, home was she. Every one that knew her felt the gentle power Of Rosalie the Prairie Flower.

But only by artificial means could she continue fair as a lily on the prairie. And that far-reaching gentle power! Would she make home happy? We, the plain people prefer Hoosier Sal who gets Rosalie's tune.

Sweet as a posy, brave as a lamb, Peaceful and happy as a fresh water clam, Every one that knew her said there was no gal That could compare with Hoosier Sal.

The Lone Fish Ball is, we are assured, founded upon a Boston fact;

The waiter roared it through the hall,. We don't give bread with one fishball.

It seems that the man with a mean appetite had previously felt his cash to know his pence and found he had but just six cents, which enabled him to buy one fish ball, but caused him embarrassment when he demanded bread with it. Little incidents like this often afford side lights on history. To enter a Boston restaurant today with only six cents in hand and pocket would require great moral courage.

In Shucking of the Corn the lack of unity calls for an informing note similar to that upon Cocachelunk,—that it is a kind of nonsense song; A little of it reads thus,

Oh! what's the matter Pompey ? Oh ! what's the matter now ? The hens they are a cackling And so's the brindled cow.

For we're going to the shucking, We are going to the shucking We are going to the shucking of the corn; And I'll meet you in the morning As sure as you are born.

Her mother (Sallie's mother) took in washing, Her name was aunty Simms; She had fourteen little children.

(At this point, although it is not in the authorized version, brother Bones should inquire in a deep and husky voice, "And wat did she do wid all dose fo'teen little chillen?" To which the whole company replies)

Oh, she'used them for clothes pins

The pith of this merry conceit is of course that Aunty Simms should have fourteen little children contemporaneously of a size fitting for clothes pins. Rabbits and guinea pigs take notice.

This one of several songs by Dr. Holmes for the class of '29,—but 1829 and Harvard,—catches the eye;

Where are the Marys and Anns and Elizas, Loving and lovely of yore? Look in the columns of Old Advertisers— Married and dead by the score.

Marys and Anns and Elizas a century ago! What are the names today?

The tunes selected still further throw light upon the simplicity of the times. There's music in the air (more often than in the tenor) was an antique when I was a boy in school. Some twenty different sets of verses—lyrics perhaps— were sung to the tune of Sparkling and Bright. Who knows it now? Benny Havens O, and Cocachelunk are numerically popular. There is multiple use of Villikins, Those evening Bells, Lauriger, Landlord fill the flowing bowl. Ellen Bayne and Angelina Baker-are unknown persons and tunes.

Many of the tunes we may believe will break out for generations as sophisticated youth weary of pleasures that affect nothing above the level—the anatomical level—of the neck revert to the hay-ride, the congregation on the moon-lit veranda or the clustered boats on the lake, and sing because they can't help it, Ben Bolt, John Brown, Susanna, The Suanee River, Massa's in the cold cold ground, Old Lang Syne, Annie Laurie ("Each heart recalls a different name, but all sang Annie Laurie")

Voice after voice caught up the Song Until its tender passion Rose like an anthem rich and strong Their battle-eve confession.

Good Night Ladies.

Although the book of songs was published only three years after the close of the Civil War very few of the war tunes were chosen for college songs. Perhaps the revulsion from that heartbreaking period made Tenting on the Old Camp Ground, Shouting the Battle Cry of Freedom, Marching through Georgia and the others utterly distasteful for the time.

There is more than a superficial meaning to the numerous adaptations of hymn tunes to merry or somber college verses. The college boys knew them, lit is difficult to think of undergraduates of the present time coming naturally to these tunes, not selected for their beauty but for their familiarity. There was old China divorced from Why do we mourn departing friends and joined to something about Mechanic's early doom, The Morning Light is Breaking, Greenville, Kind words can never die, Old Hundred, Marching along, (from the Sunday School,) Pleyel's hymn, Antioch, I'm going Home, and the tune of Where O where are the Hebrew Children.

I have perhaps poked a little fun at these ephemeral but blameless ditties. But I will add a few more serious words which have place here as the product of reversed suggestion. As one of the shy and musically uncultured millions I record my mild and ineffective protest against the hundreds of vulgarians or the other hundreds of disdainful critics who are scaring us simple folk from the songs and hymns which we the multitude love, by coarse gags or by supercilious disparagement. The hymns and songs of the people are scattered through the centuries and are simple, melodious, and rich in those sentiments which are the moving forces of humanity.

There is nothing finer than some of the ancient hymns of the mother church which for ages preserved the faith, as for instance, Querens me sedisti lassus Redemisti crucem passus Tantus labor non sit cassus; verses which Samuel Johnson could not repeat without tears.

There were noble hymns which in their simple harmony they sang in the churches a century or more ago, Majesty, And on the wings of mighty winds Full royally he rode; Rainbow, The sea grows calm at his command, And tempests cease to roar; Victory, Now shall my head be lifted high Above my foes around. Although revived only for old folks' concerts their charm remains whenever they are heard. Hymns of the English writers too numerous to quote are inspiring by their words and music. Whittier's, Dear Lord and Master of mankind, The ninety and nine who went not astray, and even What shall the harvest be, are merely instances of simple themes that hold their places in simple hearts. And why tell the world that Handel's Messiah with its resounding fugues, its pastoral symphony, its air, He shall feed his flock, its vibrating King of Kings and Lord of Lords is not good music (if it is not)? Every year the common folks crowd the largest halls to hear it.

And it is the simple songs that we love, Drink to me only with thine eyes as superbly sung by Werrenrath, The harp that once through Tara's halls the soul of music shed, Now hangs as mute on Tara's walls as if that soul were dead. O Bay of Dublin my heart you're troublin, The Lorelei, Robin Adair, Soft o'er the mountain Lingering falls the southern moon, The Woodland Lullaby are instances merely taken at random. One of our cherished athletes whose performance entitled his opinions to great respect and whose friendship I am proud to retain, confessed to me that he believed in purity in athletics but not too damned much purity. Adopting his discriminating creed let us believe in musical culture for the masses, but not too—ahem—reprobated much culture. Let the people sing the songs they love, which are sweet and wholesome in their sentiment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Oldest Building on the Campus

April 1925 By Professor Herbert D. Foster '85 -

Article

ArticleTo what has been written

April 1925 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1925 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1917

April 1925 By Ralph Sanborn -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1925 By Perley E. Whelden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1925 By Whitney H. Eastman

Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72

-

Article

Article"WHAT EVERY PROFESSOR OF SIXTY SHOULD KNOW"

January, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleSCRAPS OF PAPER

December, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Sports

SportsMERE FOOTBALL

NOVEMBER, 1926 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleFACULTY MEETING

DECEMBER 1927 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72

Article

-

Article

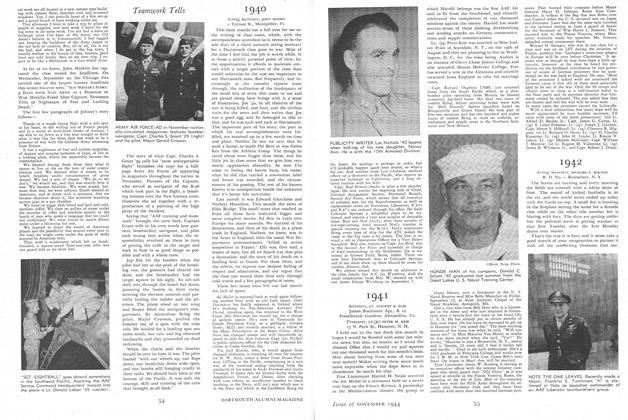

ArticleOn the job

November 1944 -

Article

ArticleMore new presidents

MARCH 1988 -

Article

ArticleVox

February 1975 By D.A.D. -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH BACK TO THE LAND

November 1940 By Robert R. Rodgers '42 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1961 By TOM DALGLISH '61 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1931 By W. H. Ferry '32