One of the results of the selective process of admissions is beginning to be apparent in that there is a distinct diminution of the numbers admissible to the freshmen classes of the future. This is due solely to the fact that the "mortality" in the classes already in college is so low —that is, that so few under the present system are being separated from the college because of delinquencies either of character or scholarship—that the established total number of 2000 students can be kept to only by a drastic reduction in the numbers admitted to the succeeding freshman class. It is the determination of the College to adhere to the general limit of 2000 undergraduates because that seems to be the largest number capable of accommodation and instruction with the present plant and teaching force; and unless there is a serious depletion of the ranks already in college by the departure of students during the year, it naturally leaves only about 500 sure places for the incoming freshman class; practically not over 550.

That the classes already in college so generally retain their strength is confidently ascribed in the main to the effectiveness of our current system of selection in yielding the sort of men capable of such good work. Naturally it is gratifying, although it entails a certain embarrassment in that the narrowing of the scope of the incoming class makes it necessary to deny admission to many who have apparent qualification, but who must be refused because of the pressure on the available space. The familiar recent figure—say 650 freshmen—now has to be cut by 100 or so in' order to keep the total undergraduate strength down to the stipulated 2000; and in cutting thus there is bound to be a plenitude of cases in which there is material for regret. The normal freshman class of the future, if the 2000 limit is retained and if the upper classes maintain their present ability to sustain their numbers throughout *the four years of their course, will number around 500. In fact, roughly speaking, that would also be the approximate number in each of the four classes. Everything depends on the ability of each successive class to maintain its membership unimpaired by losses; and, as has been said, this ability has shown such a marked improvement within the past year or two that next fall's entering class will necessarily be smaller in numbers than recent predecessors. As a testimony to the efficient working of the selective process it appears to be entirey satisfactory and convincing.

Breaking his custom, which is to avoid the use of "form letters" for any purpose, the President has been compelled by the great and increasing number of instances in which promising applicants have had to be refused registration to resort to such a letter explaining the situation to such applicants and their families. In it he explains that "hundreds of applicants are being denied enrollment at Dartmouth, not because they are not capable scholastically, or because they are not desirable and attractive prospects in other ways, but simply because they do not rank with other men who, according to the data available, seem to be better prospects." That means only that an applicant now has to be rather more than pretty good if he hopes to be enrolled— he needs to be extra-good. He has to take his chance among some 1500 or 1600 rival applicants for only 550 available places. If he falls short, it does not by any means necessarily imply that there is a positive deficiency in his caseindeed there are pretty sure to be some 300 men out of the rejected thousand who'm the College would be glad enough to take if only it had the room, and would have accepted gladly enough two or three years ago, but whom it must now weed out because others of the 1500 applicants strike the authorities charged with the task as being even better qualified. Rejection, in fine, is no disparagement in these circumstances. In hundreds of the cases it is merely hard luck, for which the College is as sorry as any one elseespecially because it makes no claim to omniscience and is certain to make mistakes here and there among the men it does choose on the face of their apparent records.

The long and short of it is that a Dartmouth freshman class must at the moment be limited to 550 men at the outside, with every prospect that the limit will be somewhat lowered as time goes on. The system now used for selecting candidates for admission seems to be producing a steadily better quality of students, so that fewer are falling by the wayside as they go along. This reacts to curtail the size of subsequent classes, and the picking and choosing must therefore be more rigorously done than ever.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S 158TH COMMENCEMENT

August 1927 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICIAL FITNESS V.

August 1927 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D., -

Article

ArticleJUNE MEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

August 1927 By J. R. Chandler '98, Clarence G. McDavitt '00 -

Article

ArticleTRUSTEES HOLD MEETING IN HANOVER

August 1927 By Hanover, N. H.,, E. K. Hall -

Sports

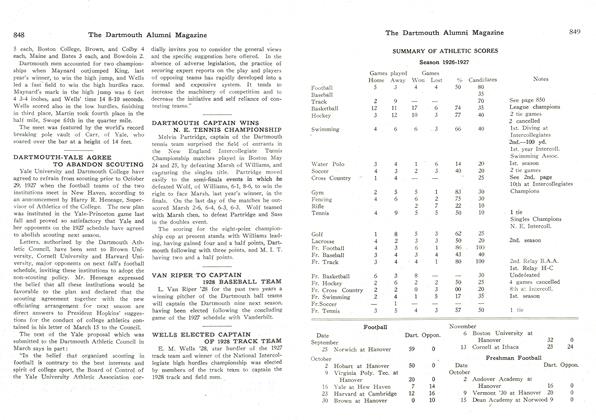

SportsSUMMARY OF ATHLETIC SCORES

August 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

August 1927 By Herrick Brown