The nations are lined up for the marathon of modern history. Spain and Portugal speed out in front and build a commanding lead. The pack approaches the bend of the 17th century and here comes France. Holland has reached her stride and is dropping behind. The lead changes hands several times: first France, then England. And now, into the stretch, it's England, England, England.

Germany is pulling fast. Now comes America. England is holding her pace but the lead is vanishing. America and the Soviet Union - yes, even the French and Germans, sidelined for a moment with injuries - are moving fast. England is still there, though, moving swiftly, surely, the same pace, even a bit faster. But now she is surpassed. America, the Soviet Union, Germany, Japan - they hurtle ahead.

Faster and faster they go and England is falling farther and farther behind. It is a gloomy sight. Discouraged, some of her organs stop working. Even the spectators begin to ridicule her, the once-proud titan of the race.

So it is. Great Britain's economic advance was more rapid in the 30 years after World War II than at any time in the Victorian period, when her lead - and her mettle - was commanding in every respect. Indeed, the gains made in the neither happy nor glorious quartercentury of Elizabeth's reign are startling. The standard of living is higher, the base of wealth broader. Macmillan's unfortunate phrase still holds: the British never had it so good.

"Far from being sick," writes Bernard D. Nossiter, the Washington Post's London correspondent, "the place is healthy, democratic, as stable a society as any of its size in Europe." To be sure, there are problems - the unions, the Asians, Ulster - but the greatest problem is lodged in the greatest resource, the mind and the spirit of Britain.

Nossiter's argument, deftly made, is that Britain's problem is not in her pocketbook but in her psyche. The nation according to Nossiter is not on the decline; it is, in fact, on the rise, though others are on the rise, too, and at a faster pace. It is not because, as myth would have it, British businessmen have (1) lost the sparkle of entrepreneurship, if indeed they ever had it; or (2) devoted .too little attention to capital improvement.

Rarely do those whom the Times (in a less democratic age) called "the best people" direct their energies into industry. Few soil their hands with money if there is an opportunity to toil in the Foreign Office or Broadcast House. Besides, as Nossiter adds, British industry does not welcome the well-educated.

Not to worry, Nossiter counsels. The tendency of Britons to covet leisure over goods will pay off in the end. Britain's future is far from the ignoble strife of industry; it is in the gentler arts, in words, music, banking, education. "The day that the last mine, mill, and assembly line close should be an occasion for national rejoicing, not despair," he writes.

Perhaps. The arts and the printed word are the current repositories of Britain's strength. But it wasn't always that way - Manchester and Birmingham and Wolverhampton weren't built on Shakespeare alone, and one wonders if they could survive on Stoppard.

BRITAIN:A FUTURE THAT WORKSBy Bernard Nossiter '47Houghton Mifflin, 1978. 275 pp. $9.95

A reporter for the Buffalo Evening News, David Shribman was infected by Anglophilia asa Reynolds Scholar in 1976-77.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCrime and Punishment

December 1978 By Tim Taylor -

Feature

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureParadise Lost or Paradise Regained?

December 1978 -

Feature

FeatureGOOD NEWS

December 1978 -

Article

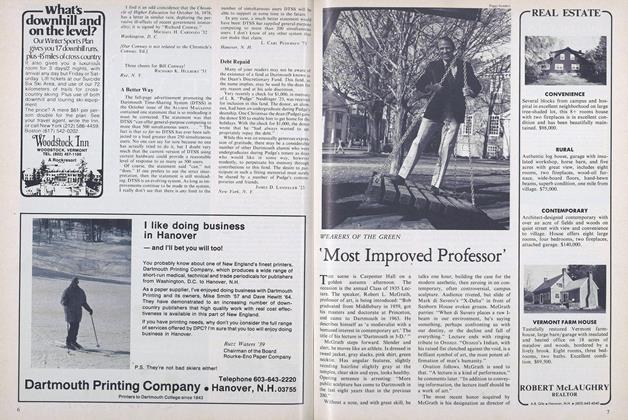

Article'Most Improved Professor'

December 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleStraight Shooter

December 1978 By D.M.N.

DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

SEPTEMBER 1983 -

Article

ArticleA Son's Reflections

January 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

FeatureLap After Grim Lap, Note After Sparkling Note

April 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleDiplomacy's Medium

December 1979 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Books

BooksDisorderly Houses

October 1980 By David M. Shribman '76 -

Books

BooksBecoming Yankees

SEPTEMBER 1981 By David M. Shribman '76

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

May 1929 -

Books

BooksA Study of Student Life-the Appraisal of Students Traditions

May 1935 -

Books

BooksAn Overlooked Early Collection From the Rocky Mountains

May 1936 -

Books

BooksMICHELANGELO, THE MAN

June 1935 By Hugh S. Morrison -

Books

BooksNEUROLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY FOR GENERAL PRACTICE

May 1951 By NIELS L. ANTHONISEN, M. D. -

Books

BooksELEMENTARY THEORY OP FINITE GROUPS.

February, 1931 By Robin Robinson