La Grande Semaine des Nations Américaines. Editions FraneeAmérique, Paris, 1930, P. 9.

Director of the American University Union, Paris

THE INVITATION of the editors of the DARTMOUTHALUMNI MAGAZINE to prepare this article—and to prepare it for the present issue—is an honor that the writer highly appreciates. He has written the article with genuine and lively pleasure; a pleasure tempered, however, by the reflection that he is sure to have, under the circumstances, a most exactingly and competently critical circle of readers. He begs in advance the. indulgence of these readers for any sins of omission or commission of which, despite the best intentions, he may be found guilty in the following pages.

BOYHOOD AND YOUTH—EXETER ANDHANOVER

CLIMBING THE family tree is not an exhilarating pastime, and, for present purposes, a few words of genealogical data will suffice. Be it said, then, that Edward Tuck, the subject of this sketch, is the ninth in descent from Robert Tuck, born in Gorlston, Norfolk, England, one of the founders of Hampton, N. H., in which town he settled in 1638, and where his descendants lived until 1807. In that year, one of them, John Tuck, moved just across the state line into Parsonsfield, Maine. There Amos Tuck, son of John Tuck, and father of Edward Tuck, was born in 1810.

No one can well understand Edward Tuck without some knowledge of his immediate forebears and of the New England milieu in which he was born and bred. His grandfather and his father, each in his own way, were typical embodiments of the New England spirit, and it was, in large measure, that spirit that formed him and gave his nature the bent it was to take.

Happily for the biographer, a document still exists—- the Autobiographical Memoir of Amos Tuck (1875)— which brings the reader close to John Tuck, Edward Tuck's grandfather, and to Amos Tuck, his father. It will be noted that certain traits, which the Memoir lifts into relief in painting John Tuck's portrait, were vital in the second generation, and are still vital in the third. John Tuck is presented as a man of alert intelligence and cool judgment; amiable, happy, gay and companionable, but essentially serious, and of firm independent convictions. He was rebellious against the Calvinistic theology then dominant in New England, and, to quote the words of the Memoir, "of a spirit that negatived all repulsive dogmas." The tendency toward freedom in religious thought persisted in his son, who, under the influence of Channing and his associates, was to become a Unitarian. It is further set down that John Tuck never missed a chance of impressing the minds of his children "with the importance of education and good conduct, as superior to the acquisition of wealth."

Amos Tuck was a man of mark, alike by a personality singularly attractive and engaging and by the place he took in the life of his town and of the state. His character and career, familiar to Dartmouth men, call for only passing attention here. Shortly after graduation from Dartmouth, he settled in Exeter, where he became a man of leading influence and of substance, and one of the best lawyers in the state. In Exeter, his son Edward Tuck was born on August 24, 1842. As a hater of slavery, he risked the loss of clients and his political future in the service of the cause he had at heart. Elected to Congress as one of only three "Free-Soilers," he served three terms—from 1847 to 1853. He was called the Voice of the State. It was he who in October, 1853, first proposed the name "Republican" for the party that united under its banner the anti-slavery elements of different parties. There was in him—and in his appearance—a something of ardor and disinterested devotion that rallied around him a circle of loyal friends and admirers. Theodore Parker said "To look upon Amos Tuck is a benediction." A public-spirited citizen, he gave largely in proportion to his means. He was for a long series of years a trustee of Phillips Exeter Academy and of Dartmouth.

Fortune, always kind to Edward Tuck, smiled upon him when it ordained that he should pass the impressionable years of his youth in a town and in a circle where, consciously and unconsciously, he drew in, as the breath of his nostrils, the spirit of New England culture and aspiration, when both were in full flower.

Exeter, then a town of some 3,000 souls, had already, in the middle of the last century, and still has for that matter, a nation-wide reputation as the seat of one of the best schools in America—the Phillips Exeter Academy. It was at this school that Edward Tuck prepared for college. The principal of the Academy and its group of professors and their families gave the town a tone and atmosphere of culture rare in American villages of its size. More than this, New England was never more vitally alert and alive, emotionally, intellectually, and politically, than in the years of Mr. Tuck's boyhood. Exeter, sensitive to all that was astir, felt the heartbeats of New England and of the nation as well. The New England literary movement was at its height when Edward Tuck was a boy at Exeter. He likes now to relate to his friends how, as a youngster, every week, so to speak, brought to the tables of his elders one or another of the works that were to constitute America's most lasting contribution to literature. He remembers when the songs of Longfellow and Whittier filled the air. He was not without personal contacts that made the literary movement a living reality for him. Whittier he knew as his father's close friend. Those about him were listening to Lowell, as he recounted his adventures with literary masterpieces of the past, or laughing with Oliver Wendell Holmes. Young Edward Tuck, taken by his father to visit Emerson, himself heard that "voice oracular" which then held the ear of all that was best in America.

Edward Tuck's life at Dartmouth, whither he went in 1858, passed happily, and, in all that concerned the daily academic round, tranquilly. His mind, however, was active and adventurous, and did not stick to the beaten track. He was face to face, with new ideas and points of view before unknown to him. He rejected this, accepted that, and the point of interrogation had its place in the punctuation of his reflections. He was, in short, finding himself. Indeed, it is perhaps safe to say that his nature had already taken its bent, and that, at graduation, he faced the world with, essentially, the convictions and the compact practical philosophy of life that are his to-day. Two points in his college career may be noted—and then, pastures new.

It should not be forgotten that William Jewett Tucker (class of 1861) and Edward Tuck were close friends in college days, and, for a time, roommates. It was Dr. Tucker's election, years later, to the presidency of the College, and his influence that were to kindle Mr. Tuck's practically ardent devotion to the College. Let it be at once added that the ardor of this devotion was certainly not cooled when, by signal good fortune for Dartmouth, the mantle of President Tucker fell upon the shoulders of Ernest Martin Hopkins, a man after Mr. Tuck's own heart.

In 1862, on graduation, Edward Tnck was Class Orator. His "oration" has been preserved, and the document is of prime interest biographically. The boy is father of the man, and there is much, in that youthful production, of the Mr. Tuck of to-day. The oration is a defense of the liberal arts college which aims to train and enrich the mind, to give perspective and a sense of relative values, to provide the student with touchstones of excellence that will enable him to distinguish —and so to distinguish is the mark of the man of culture —the excellent, alike in letters and in life, from the mediocre and the third rate. Edward Tuck saw clearly that what Dartmouth aimed to give was precisely what he wanted. That he stood second in his class and that he was a Phi Beta Kappa man is proof that he strove to profit by what was offered to him academically. His oration is variously exceptional, negatively by its freedom from the banality often characteristic of such performances, and, positively, by its clear thinking, its play of ideas and the orderly arrangement of them, its good pure English, and, above all perhaps, because it is alive—the genuine, direct expression of what he himself thought and felt. Note the good words, an earnest of deeds to come, with which the oration ends:

"If hereafter our paths of labor ever meet, let us extend to one another the generous and sincere right hand of friendship. Whatever be said of us, let it never be said that, as sons of the same Alma Mater, we could not be both honest and charitable, manly and unselfish, always ready to lend a helping hand to any brother not as fortunate, though as deserving, as ourselves."*

AN INTERLUDEPARIS ANDTHE AMERICANCONSULATE

COLLEGE STUDENTS, in Mr. Tuck's day, aimed, well nigh all of them, at a profession. Mr. Tuck chose the law, returned home to Exeter, and plunged with such energy into Blackstone that his eyes failed him. The Civil War was then at its height, and he enlisted in the United States Navy, only to be refused on the score of the trouble with his eyes. His oculist prescribed an ocean voyage and consultation with a Swiss authority—- oculists of that nation being then in specially high repute. Following the prescription, Edward Tuck embarked—one of two passengers—on the Isaac Webb, a fast old clipper-ship, which made the voyage to Liverpool in only nineteen days! He carried letters of introduction to our Minister in London—there was then no American Embassy in London, nor, for that matter, in Paris—Charles Francis Adams, and to our Minister in Paris, William L. Dayton, both friends of his father, who had known them well in Congress. He arrived in France early in 1864, and remained there for a few months, partly in the Latin Quarter in Paris, partly in a French private school in the little town of Dourdan, where he picked up French enough for conversational purposes. Then followed, in May, a sojourn in Switzerland, where, at Berne, he visited his father's friend, George G. Fogg, the American Minister. Thence he went to Geneva. Oculists were consulted there, and the young patient, almost cured of his malady, was pronounced once more ready for reading, or for study. While in Geneva, in August, out of a clear sky, there came to Edward Tuck a surprising notice from our State Department, directing him to report at the American Consulate in Paris for examination as a Consular Clerk—a situation for which his father, and Professor Patterson of Dartmouth, his father's and his own friend, then U. S. Senator from New Hampshire, were responsible. At the Consulate he was told to prepare for his examination. On the committee that examined the young candidate for the Consular post were our Consul, Mr. John Bigelow, who was to become a life-long friend of Mr. Tuck's, our Minister, Mr. Dayton, and a Consular Agent. One subject set for the examination was the Constitution of the United States. The candidate, by way of preparation, threw himself upon the Constitution as he had two years before thrown himself upon Blackstone, and, thanks to his phenomenal memory, soon had the whole document by heart. He tells, and with relish, how, when quizzed by his examiners, he poured over them such a verbatim deluge of constitutional articles that, to escape the flood, they turned their quiz to other themes, on which, they hoped the wouldbe Consular Clerk might prove less voluble. Mr. Bigelow, years later, remarked to Mr. Tuck that "he was persuaded at the time that he had the whole Constitution written on his cuffs or somewhere."

The examinations passed, the new appointee, with his commission signed by President Lincoln and Secretary Seward, was hardly broken in to his duties when Mr. Dayton died—in January, 1865. Mr. Bigelow replaced him as Minister, and Edward Tuck, at the early age of twenty-two, was made Vice-Consul and for five months Acting Consul of one of our two most important consulates. At the end of this period, the future biographers of Lincoln, John G. Nicolay and John Hay, who had been Lincoln's Secretaries, were appointed to Paris, the one to replace Mr. Bigelow as Consul, the other to be Mr. Bigelow's First Secretary of Legation, John Hay and Edward Tuck became intimate friends, dining out often together, and taking lessons, as was the custom for young Americans in Paris in those days, at the same fashionable dancing-school. It is worth noting that the Consular Reports sent out from our Consulate in Mr. Tuck's time were highly commended in a speech made by our Consul General, Mr. A. Gaulin, in 1929, in which the latter praises "the efficiency displayed in them by the young Vice-Consul, now the Dean of the American Colony in France."

Mr. Tuck, having decided that there was no sufficient future in the Consular Service as a career, resigned his position in 1866, and was on the point of returning home, when John Munroe & Company, then the only American bankers in Paris, offered him a post, anticipating the need of a helping hand during 1867, the year of the Universal Exposition. Mr. Tuck stipulated for time to return to America and consult his father. He did so, and accepted the post. He was then requested to remain temporarily with the New York House of Munroe. The delay was not to his taste. Paris had cast its spell on him, as it has on many another, and he longed to return. His sentiment for the Ville Limiiere was perhaps like that of an American student who, seeking a permanent post in Paris, at the end of a year's studious sojourn, was asked "Why stay in Paris? Don't you love your own country?" "Yes, I love my country" was the reply, "America is my mother; but Paris is my best girl." As in the young man's case, so in Mr. Tuck's, both sentiments were genuine. As it happened, however, Mr. Tuck's services were so much needed in New York that five years were to pass before his next visit to Paris.

NEW YORK JOHN MUNROE AND COMPANY

PUTTING THE thought of Paris in the back of his mind, Edward Tuck set to work with enthusiasm to master all the details of banking and the exchanges. He had a flair for business and a liking for it, and also a capacity for sustained hard work. Ambitious of success, he was ready to pay the price for it. Not content with what his own experience taught him, he read evenings, studying banking, especially currency problems, and beginning a collection of books on those subjects which some years ago he presented to the Chase National Bank. One result of these studious evenings, combined with first-hand knowledge of his own, was a series of articles and letters which he contributed from time to time to The Forum, The London Economist, The Statist,The Nineteenth Century, etc.—articles notable by their vigorous logic and the ease, point, and lucidity of their style. In January, 1871, in his twenty-ninth year, after less than five years of apprenticeship, he was made a partner in Munroe & Company—an exceptional achievement and one not within the reach of the first comer. He had set himself, from the beginning of his business life, to put into practice certain principles and maxims which his father's example and precepts had indelibly impressed on him. These principles and maxims he himself set forth in the following terms, in a letter to President Tucker, which is familiar to every student and graduate of the Tuck School:

"absolute devotion to the career which one selects, and to the interests of one's superior officers or employers; the desire and determination to do more rather than less than one's required duties; perfect accuracy and promptness in all undertakings, and absence from one's vocabulary of the word 'forget'; never to vary a hair's breadth from the truth or from the path of strictest honesty and honor."

Mr. Tuck seems to have personified the qualities the letter commends. In any event, Munroe & Company, then one of the important New York banking firms, promptly recognized in him a man of rare business ability, of perfect integrity and dependability, and one to whom heavy responsibilities could be entrusted.

For the first five years of his connection with the firm, he did not quit New York. In 1871, just after he had been made a partner, he left for Paris on a business trip, and arrived when the Commune had thrown the city into turmoil. He was invited to stay at the home of Mr. George E. Richards, a partner of the House of Munroe. Then and there he met Miss Julia Stell, Mr. Richards' ward, an orphan daughter of a prosperous and successful American merchant and banker whose business interests had made him for years a resident of Manchester and London. After the death of her father and mother, she became a member of the Richards family.

The year 1872 is a red-letter year in Mr. Tuck's life. Miss Stell, some months after meeting Mr. Tuck in Paris, went for a visit to America, whither Mr. Tuck had preceded her. They Became engaged in New York, and she returned to Paris, Mr. Tuck following later. They were married there in the American Church, on April 23 of that year. The marriage proved an ideal union. It brought enduring happiness into Mr. Tuck's life, and gave him as companion a rare woman, distinguished by many superior qualities.

From 1872 to 1881, Mr. and Mrs. Tuck made New York their home, though, in fact, they divided their time between that city and Paris, whither the affairs of the bank continually called Mr. Tuck. In 1881, having acquired a comfortable independent fortune, Mr. Tuck resolved to be done with the confinement of routine business, and retired from Munroe & Company. His retirement can be a mystery only to those who find entire satisfaction in business activity. Mr. Tuck did not seek a new partnership. Banking, however successful, did not have the highest place in his scale of values. He was, in fact, a heretic as regards one article which has, not unnaturally, all things considered, slipped into the American creed—the article which exalts being busy, for the sake of being busy or as the road to wealth, to the rank of a cardinal virtue.

A decision to take up a residence abroad virtually ended, in 1889, Mr. and Mrs. Tuck's New York lifeand what may be regarded as the second chapter in Mr. Tuck's career.

FRANCE

IN speaking of Mr. and Mrs. Tuck's life in France, it will be convenient to disregard strict chronology and simply to give glimpses of the activities that are typical of them. To both Paris was familiar. In 1889, they established themselves at No. 146 Avenue des Champs- Elysees,moving, in 1895, into a spacious apartment at No. 82 of the same avenue, familiarly known to their friends as "82," which was to be their Paris home henceforth, and which is still Mr. Tuck's Paris home. To that apartment belong many souvenirs dear to Mr. Tuck. One of them may be mentioned as sure to interest his compatriots. Monsieur J. J. Jusserand and Miss Elsie Richards were married from there in October, 1895. Miss Richards was the daughter of Mrs. Tuck's guardian, and she, as a little girl, had carried Mrs. Tuck's train at her wedding. Monsieur Jusserand and Mr. Tuck have for long years been intimate friends, and this friendship between the best loved of French Ambassadors to the United States and the American who, as a private citizen, holds a like position in the hearts of the French is pleasant to contemplate.

The Champs-Elysees, then generally regarded by New Englanders as, along with the Milky Way in heaven and Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, one of the loveliest of thoroughfares, showed no signs, in 1895, of the encroachments of business that have since the War changed its tone and aspect. There was ample room then for the leisurely pedestrian, and, between the broad sidewalks, for the stream of broughams, victorias, and fiacres. Mr. Tuck's figure became a familiar one on the Avenue, as, with his dogs, he took his morning constitutional—square-shouldered and of strong frame; tressoigne; clear, gray-blue eyes with a living light of amiable humor in them; a certain bonhommie in his aspect, but a certain dignity, too, that did not encourage easy familiarity. There was indeed, it may here be remarked in parenthesis, a something in Mr. Tuck's appearance—as in that of his father—that struck everyone's attention, a something of essential kindliness, good will, benevolence, and friendliness. The writer recalls an instance of this. On leaving Mr. Tuck's apartment in the company of a French friend who had never before met Mr. Tuck, the friend exclaimed "Ce monsieur porte la bonte sur son visage."

In the early years of their residence abroad, Mr. and Mrs. Tuck made frequent sojourns in America, traveled considerably, and, when in Paris, received hosts of Americans and many distinguished French friends. While they attended properly to their social duties, they were never willing to accept the exacting and unprofitable obligations involved in playing a regular r6le in the organized life of society with a big "S." Though a member of several New York and Paris clubs, Mr. Tuck is not, and never has been, a club man. Never a smoker himself, he does not relish smoky club rooms and long, idle hours, which leave behind them only the smoke and ashes of gossip and small talk.

Mr. Tuck is a "gentleman of leisure" only in the sense that he is the master of his own time. In New York, even after quitting Munroe & Comany, he found himself caught up in the current of "big business." He was one of those who, in 1886, obtained control of the Chase National Bank, of which he became a director. He made the acquaintance of leading men of affairs in various fields, among them James J. Hill, with whom he was associated in the construction and development of the Great Northern Railway. His stake in the development of the Northern Pacific Railway was also large, and had an important influence upon his fortunes. A resident of Paris, he kept in close touch with some of the best business heads in America. His own sound judgment and vision of future developments at home, aided by information received from trustedbusiness friends across the sea, shrewdly directed his financial operations. He could well contemplate with satisfaction his substantial participation in the early organization of such industrial enterprises as the United Gas Improvement Company and the Electric Storage Battery Company. His fortune grew steadily in the nineties, and he was, before the opening of the present century, in a position to transform into munificent acts the sentiment with which he concluded his Class Day oration.

In making the first important benefaction in the long series of his gifts, Mr. Tuck's thoughts turned to home and to Dartmouth. In 1899, on one of his frequent sojourns in America, he called on his old friend of college days, Dr. Tucker, then President of his Alma Mater, and provided for the founding of the Amos Tuck School of Administration and Finance—the first collegiate institution of its kind in America, antedating by ten years that of Harvard. Space forbids a detailed account of the gifts which continued to flow to Hanover. Such an account is, indeed, unnecessary here, for what Mr. Tuck's assistance meant Dartmouth men well know. It meant that Dartmouth could not have attained the enviable place it now holds among American colleges without such generous and timely support as its greatest benefactor furnished.

In his devotion to his Alma Mater, Mr. Tuck did not forget other American institutions. The crying need of a suitable home for the New Hampshire Historical Society in Concord led him to give the Society the imposing structure, so rarely beautiful architecturally, in which it is now housed—and with the building a maintenance fund. The Phillips Exeter Academy and the Exeter Hospital and its Nurses Home were generously remembered. Hampton received from him its Memorial Park and Athletic Field. To the Boston Museum of Art went the precious Houdon bust of Washington. The French Hospital in New York, the New York Diet Kitchen, the Alliance Frangaise in America, and many others have excellent reasons for recognizing his generosity.

In 1898, Mr. Tuck purchased the estate of VertMont for a summer home. The property is about eight miles from Paris, situated in the Commune of RueilMalmaison, a town of some 13,000 souls. The park, with its chateau, its wide lawns, its bright -parterres, its venerable trees, its gardens, its greenhouses and other dependencies, is one of the loveliest in the environs of Paris. Here in summer Mr. and Mrs. Tuck were wont to give innumerable lunches and dinners, and occasional garden parties and dances. The Visitors Book of Vert-Mont, with that of "82," is a roster of most of the American not abilities who have been residents of, or visitors to, Paris, during the last thirty odd years, and of many distinguished foreigners as well. The long line of American Ambassadors have, one after another, been guests at Rueil, and several of them, not forgetting Ambassador Myron T. Herrick, were Mr. Tuck's close friends. The guests at Vert-Mont have included, too, most of the Americans who have been active in the life of the American Colony.

Mr. and Mrs. Tuck delighted in receiving their friends both in Paris aarl in the country. They were accomplished hosts. Mrs. Tuck's quiet dignity and slight reserve, Mr. Tuck's urbanity, prompt wit, and bonhommie happily combined to create a social atmosphere which warmed into genial expansiveness guests of the most different kinds and temperaments. The circle they drew about them had its own individual social nuance. A principle of selection reigned, which was democratic, and not primarily one of social position. They liked to assemble at their table those who were playing an active and representative role in the world of affairs, of art, of diplomacy, of letters, of journalism, or those who commended themselves by their intelligence, social gifts, or general agreeability. Mrs. Tuck kept a good house. If one were to make a flat statement to the effect that nowhere on this planet does one fare better gastronomically than at "82" or at Vert-Mont, he would probably find no contradictors. It would be inexcusa ble to ignore here the fact that there is a cellar, too, at "82," and another at Vert-Mont, to both of which thirsty souls with highly educated palates pay ardent and discriminating hommage.

Mr. Tuck has always been an admirer, and an assiduous reader of Benjamin Franklin. They are, in fact, kindred spirits. Certain resemblances are obviousthat of their careers in France, for instance, though this resemblance should not be pressed too far. Each is American to the core, and yet in each there is the instinctive fondness for the esprit francais. A ceaseless flow of humor—a humor not without its audacitiesis characteristic of both. Their philosophies of life are decidedly comparable. A passage from a letter of Franklin to his mother has been for Mr. Tuck a kind of device: "The years roll by and the last will come, when I would rather have it said 'He lived usefully' than 'He died rich.' " This quotation is engraved upon the fine monument of Aberdeen granite in the Tuck burial plot in the Cemetery of St. Germain, a few miles from VertMont.

Though not a devotee of sport, Mr. Tuck likes the open air and walking, making hay on his property when the sun shines, automobiling, and nature. Both Mrs. Tuck and he adored flowers, and their greenhouses and gardens supplied them bountifully—and many of their friends, too—winter and summer, with roses and beautiful blooms of all kinds. They found diversion, as has just been said, in sociabilities; in the theatre, too. They enjoyed their box at the opera, admirably situated in the middle of the "horseshoe," and they put it often, as Mr. Tuck still continues to do, at the disposal of their friends. With no aversion to diversions, the activities that really absorbed them were, however, of another kind.

Soon after their establishment at Vert-Mont, Mr. and Mrs. Tuck began to interest themselves in their humble neighbors of Rueil-Malmaison. There was no hospital in the town nor in the neighborhood. One was badly needed. The care of the sick was a problem. A large part of the population was poor. Mrs. Tuck drew close to the women and to the young girls, and became their trusted counsellor in sickness and in trouble. The situation of the girls presented a second problem. Left much to themselves while their parents were at work, they ran about the streets, exposed to demoralizing influences. Desirous of making a contribution to the happiness and well-being of the working people, Mr. and Mrs. Tuck turned their attention to the two problems referred to. After reflection, they came to a decision, which finally took concrete form. They built the Stell Hospital (Hopital Stell), so named after Mrs. Tuck's mother, accommodating thirty beds at first and later sixty, which 1903, and the School of Domestic Economy (Ecole Menagere), which opened in 1906, to receive eventually seventy pupils—girls of from nine to fourteen years of age. Both institutions were supported by their founder, and their services were gratuitous.

The story of the founding of these two institutions is typical of the way Mr. Tuck went about his benefactions. His philanthropies, taking their point of departure in a recognized need, were not hit-or-miss, burdensome for lack of maintenance, ending with the signing of a check, and leaving to others the difficulties and tribulations involved in transforming generous impulses into serviceable organizations. Before planning the Hospital, an architect was sent to America to study the best examples of hospital construction there, so that the latest medical and surgical appliances and hygienic improvements might be incorporated in the projected building. The result was a hospital, set in a park of about four acres, complete in every detail, cheerful, and homelike within and without. An out-patient department, nursing service, and bread-and-meat card service for the destitute immensely increased its usefulness. The organization of the School of Domestic Economy, as Mr. and Mrs. Tuck planned it, involved complicated difficulties. It was necessary to prepare the girls for the same examinations that faced pupils of the public schools, and, in addition, to find time in the curriculum for the instruction in cooking, sewing, dressmaking, hygiene, etc., which would make of them competent housewives or domestics. The difficulties, after experiment and modification, were overcome, and the School proved a triumphant success.

To the Hospital and its patients, to the School and its pupils, during their studies and after their graduation, Mrs. Tuck gave herself without reserve. In the supervision of both establishments, she evinced rare executive ability, and, together with a firm hand in direction, a tact and essential kindness which won her at once the esteem and affection of all those who collaborated with her.

Some years before Mrs. Tuck's death, Mr. Tuck deeded the School, and the Hospital with its large endowment fund to the Department of Seine-et-Oise, subject to Mrs. Tuck's absolute control and management during her lifetime.

The two institutions just mentioned were not the full measure of Mr. and Mrs. Tuck's solicitude for the people of Rueil. Mr. Tuck presented to the town the land for a public park, and a plot for a school building. In 1910, when the Seine overflowed its banks and flooded the town, he and Mrs. Tuck came to the rescue, housing some eighty of the townspeople left temporarily homeless. More than this, appeals for help from the needy were never made in vain.

On one side of Mr. Tuck's property of Vert-Mont, and adjoining it, was the fine estate of Bois-Preau. On the other side, and at a stone's throw from the gate of his own park, were the Chateau and grounds of Malmaison. The three properties together constituted, substantially, the Malmaison domain of the Empress Josephine, which was divided after her death. Malmaison was a favorite place of sojourn for Napoleon and the Empress. Souvenirs of them are everywhere in Rueil-Malmaison, and they naturally appealed to the imagination of Mr. and Mrs. Tuck. Two years before Mr. Tuck purchased Vert-Mont, Malmaison had been presented to the State and turned into a Napoleonic museum, which for years was poor and struggling. Its successive Curators were frequent visitors at Vert-Mont, and the institution became one of Mr. and Mrs. Tuck's three chief interests in Rueil-Malmaison, the first two being philanthropicthe Hospital and the School—and the third historic and artistic. The chdtelains of Vert-Mont were for years always on the alert for Napoleonic souvenirs as they came on the market, purchased many of the finest for the Museum, and thus contributed materially to the building up of its collections.

Place may be found here for the gist of a good story connected with the latest in the long series of treasures which Mr. Tuck presented to Malmaison—the latest and by far the most valuable. The reference is to the famous Table des Marechaux, ordered from the Manufacture of Sevres by Napoleon himself in honor of the victory of Solferino. It is a circular table, in the top of which are set miniatures, painted by Isabey, of Napoleon and his marshalls. In 1929 it was put up at auction by its owner, the Prince de la Moskowa, a descendant of Marechal Ney. Mr. Tuck wished to save it for Malmaison. By a curious accident, he discovered that his rival for its possession was none other than William Randolph Hearst.

"When I learned that," Mr. Tuck said, "I resolved to have the table, even if I had to go without butter on my bread to get it." He got it— to the tune of 400,000 francs (about $16,000). A tidy sum, but he had no regrets, as those can testify who have seen the smile of profound satisfaction with which he tells the story.

The greatest of the gifts of the Maecenas of Malmaison to the Museum remains to be recorded—kept to the last, though in point of time it ante-dates the gift of the Table des Marechaux. From his own property, Mr. Tuck looked out upon the estate, already mentioned, of Bois-Preau, forty-five acres in extentmeadows, ponds, and streams, and the chateau—all framed and bowered in groves of ancient trees. He reflected that, if the Bois-Preau park and chateau were joined to the park of Malmaison, Josephine's historic domain would be, in large part, reconstituted. More than that, the Museum was now filled to overflowing with souvenirs of Napoleon. The Bois-Preau chateau would serve as a much needed annex. He caressed the idea of purchasing the whole estate. The idea was finally realized. In 1927, Mr. Tuck presented BoisPreau to the French Government, to be adjoined at his death to Malmaison.

In the years that followed close upon the founding of the Hospital and the School, the activities of Mr. and Mrs. Tuck multiplied rapidly. There were the institutions of Rueil, responsibilities in Paris, social engagements, guests coming and going, voluminous correspondence, about one hundred souls in their employ in town and country. Indeed their multifarious occupation would quite have overwhelmed them, but for the good fortune of having a precious collaborator, Mr. Lurton Burke, most affable of men, most competent of secretaries, accomplished bilinguist, and loyal friend, who, now for some twentyfive years, has thrown himself with devoted zeal into all Mr. and Mrs. Tuck's undertakings.

In Paris, as in Rueil, Mr. Tuck was pre-occupied with those for whom Fortune's cornucopia held nothing. RoOm is wanting here even for a bare record of his unnumbered benefactions. The American Hospital and the American Library in Paris have repeatedly had his aid. The University of Paris; the Museum of the Legion of Honor; the AcademiedesSciences; the Comity France-Amerique, and its Institute of American Studies, where he founded a Chair of American Civilization; the American House in the Cite Universitaire, all have been his beneficiaries. Mention should also be made of the very important Maison Maternelle, housing nearly 1,000 poor children, of which Mrs. Tuck was VicePresident. Though Mr. Tuck's mature convictions make even his father's Unitarianism seem a bondage to him, his generosity extends to organizations for social work conducted under Protestant or Catholic, as well as under secular auspices. While most of his uncounted benefactions cannot here be set down, a few are reserved for special attention later. It should not be forgotten that, in addition to his, so to speak, institutional gifts, he has befriended a host of individuals who appealed to his sympathy and merited aid, and he gave endlessly to a miscellany of charities for which friends and acquaintances solicited contributions.

The public in general has no notion of the many services Mr. Tuck has rendered to individuals at critical or difficult moments of their lives. Only his personal friends learn of them, as they crop out casually and from time to time, in conversations with him. A case in point may be cited, not so much for its own sake as because it is typical of many others that will never be known. In a restaurant in Monte Carlo to which Mr. and Mrs. Tuck went occasionally, for many years, he was struck by the zeal and intelligence with which a little omnibus (waiter's assistant) performed his humble duties. The omnibus, promoted waiter and then manager, continued to impress Mr. Tuck favorably. After some years, the waiter confessed his ambition to have a restaurant of his own and asked Mr. Tuck to lend him the funds to launch himself. The funds were forthcoming. To-day, the man in question is the proprietor of one of the choicest small restaurants in Paris, the cuisine of which appeals to the most exacting gourmets. Mr. Tuck still patronizes the establishment occasionally, and, when he does, telephones in advance to reserve his table. On his arrival, the reception is royal. The patron, remembering past kindnesses, waits at the door to receive a cordial handshake; behind him the maitre d'hotel is all smiles; the waiters anticipate every want; the chef makes a supreme effort; and Mr. Tuck's favorite table is held against all comers.

The calamitous World War, which caught France unprepared, forced the French to improvise all sorts of measures and organizations, military and civil. The American Colony, like one man, rallied to their aid. Mr. and Mrs. Tuck, lovers of France of long date, were prompt to act for the care of the wounded and of the refugees from Belgium and from the French front who poured into Paris. Mr. Tuck's friends, Ambassadors Herrick and Sharp, leaned heavily upon his aid in organizing American relief work in France—help that was precious because of his intimate knowledge of French conditions. The H6pital Stell and an adjoining building—seventy beds in all—were offered to the French Service de Sante, and was accepted by the army as Military Hospital No. 66. It was entirely supported by Mr. Tuck. As wholesome, nourishing food was scarce and hard to obtain during the War, Mr. Tuck bought a farm at Montesson, not far from Rueil, on the Seine, opposite St. Germain, so that he could supply the wounded soldiers in the Hospital with the best of meat, poultry, milk, eggs, and vegetables. The garage at Yert-Mont sheltered the ambulances that brought the wounded from the Stations to Rueil, Mr. Burke serving constantly as one of the ambulance men. Over-worked war nurses, ten at a time, were invited to recuperate at Vert-Mont. On Christmas Day, 1914, Mr. Tuck made his appearance as Santa Claus in one of the military hospitals. The Champs-Elysees apartment, its statues and art treasures retreating to corners, was transformed into a packing and shipping depot, which mobilized Mr. and Mrs. Tuck and all the domestics. There countless packages of food and clothes went off to the front or to destitute families in all corners of France. The visits of soldiers, in Paris on leave, were welcome, and no end of personal relations were established. A partial cardcatalogue of the proteges of "82" was kept, and, by the War's end, the number of cards ran into many thousands. It was in such fashion that Mr. and Mrs. Tuck served the France they loved in her hours of dire need.

The death of Mrs. Tuck, in November, 1928, bringing to an end a happy companionship and a partnership in good works of more than half a century, left Mr. Tuck very lonely. He" sought solace in watching over the charities that had been dear to Mrs. Tuck, and in carrying on his own philanthropic activities. To pay tributes to Mr. and Mrs. Tuck had become, one might almost say, a cult in France. During her lifetime, Mrs. Tuck had been variously honored. She was made Chevalier and then Officier of the Legion of Honor. To her and to Mr. Tuck jointly had been accorded the Prix de Vertu of the French Academy, never before accorded to foreigners. Her departure meant the disappearance of a beneficent force. The French expressions of grief at the loss of one who to them was the Ambassadrice de la Bonte were moving by their number and sincerity. Though Mrs..Tuck's death brought to her personal friends, American and French—and not least to her humble friends of Ilueil— a poignant sense of personal sorrow and loss, it left to them the inspiration of a life well lived.

For many years Mr. Tuck gave much attention to collecting objects of art, which he assembled in his Champs-Elysees apartment. This collection became gradually a most important one. In 1921, Mr. Tuck deeded it to the City of Paris, subject to the possession and enjoyment of it, in his own apartment, during his and Mrs. Tuck's lifetime. In 1930, he decided to turn it over at once to the Petit Palais, to which it had been destined. The collection is altogether extraordinary by the high artistic quality of every piece in it. It includes Boucher tapestries and furniture; Sevres and Chinese porcelains; paintings, not numerous but of the finest, among them five primitives; two cases of eighteenthcentury Battersea enamels and one of French enameled watches of the same period. Need it be said that Benjamin Franklin was not forgotten in this collection. He is represented by a terra cotta bust by Houdon, a portrait by Greuze, and si statuette by Gaffieri. The gift went straight to the heart of art-loving Paris. The following words of an eminent French critic and savant, Seymour de Ricci, who knows whereof he speaks, will indicate its importance: "It is one of the greatest gifts ever received by any city from a private individual. . . . What has been accomplished by this one great donation could hardly have been achieved in many years by the local authorities, even with great expense and still greater labor."

Mr. Tuck does nothing by halves. Counselled by experts, at a cost of no end of personal visits and the most meticulous patience and care, he himself supervised the arrangement of the collection in the Gallery of the Petit Palais, lowering the ceilings, dividing the gallery into salons, covering the walls with the choicest eighteenthcentury boiseries, and installing a perfect system of indirect lighting. As a result, the collection presents an ensemble unequalled in any museum in

In 1906, to escape the sunless Paris winters, Mr. and Mrs. Tuck took an apartment in Monte Carlo, which has the mildest climate on the Riviera, and where henceforth a part of each winter was to be spent. The apartment is a very aerie, with landscapes of a dream at the four points of the compass—the town below, going down in winding streets and terraces to the blue Mediterranean, which stretches off southward to the horizon; east and west, the great rock of Monaco, capes and bays, gay villas on points and mountain slopes. From the apartment windows that look to the northwest, the eye, climbing to the top of a ridge of some 1,500 precipitous feet in height, rests finally upon what appears to be a lofty ruinous tower. It is in fact the ruin of the Trophee d' Auguste, rising above the little mountain hamlet of La Turbie—one of the most imposing and significant of Roman monuments outside the Eternal City, erected in 5 8.C., a majestic emblem commemorating the definitive victory of Rome over forty-four Alpine tribes, which, finally, opening all Gaul to Roman peace and civilization, constituted the first page of French history. This trophy, daily before his eyes, struck Mr. Tuck's imagination. He visited and revisited it in walks and drives; strolled amongst the blocks of masonry and fragments of colossal statues and columns that surrounded it; and pondered over it. He sympathized with the longing of archaeologists and historians to see Augustus' great monument sufficiently reconstituted to give the beholder of to-day an idea of its former majesty and beauty. Evidently, a reconstitution of it, even partial, would be no small task. Mr. Tuck resolved, nevertheless, to undertake it. The great work, now approaching completion, goes on apace, enlisting for its accomplishment the combined toil of archaeologists, engineers, and a company of laborers. The vast blocks are being reset in their places; the inscription—happily recorded by Pliny—is being restored; great columns, which for centuries lay prone on the mountain top, are taking once more their lofty stand on the Trophy's vast base. Such is the latest of Mr. Tuck's undertakings.

Perhaps the most extraordinary feature of Mr. and Mrs. Tuck's career in France is the affection that went

tin the midst of the work on the Trophy, the original estimate of cost, which had been accepted and provided for by Mr. Tuck, was found insufficient, and he was so informed by the Chief Architect of the Historical Monuments, who was supervising that work. By way of reply, Mr. Tuck sent him verses 28-30 of the XIV Chapter of St. Luke (French Version), which read, in English, as follows:

'For which of you, intending to build a tower, sitteth not down first, and counteth the cost, whether he have sufficient to finish it? Lest haply, after he hath laid the foundation, and is not able to finish it, all that behold it begin to mock him, Saying, This man began to build, and was not able to finish."

Despite the scriptural protest, the sum needed was forthcoming. out to them from the French. Extraordinary, certainly, but natural and explicable, too. Their love of France and the French was a part of them. When they gave, their hearts went with the gifts, and increased inestimably their value to the recipients and the appreciation of them in France. On the occasion of the unveiling, in 1930, of the tablet set up in the Maison des Nations Americaines of the Comite France-Amerique, to commemorate Mr. and Mrs. Tuck's benefactions to the City of Paris, Mr. Tuck thus expressed his feelings for Paris and for France: "I am particularly grateful for including with me in this honor the beloved companion of all my life. . . . If we have accomplished anything useful to France, we have had, in doing so, the greatest satisfaction, an intimate and inner joy which has been our recompense. You know the affection which my wife and I shared for the City of Paris, where we have passed such happy years. . . . Permit me, without eloquent phrases, to tell you, in concluding, that I love with all my heart your beautiful France, and that I am proud to have remained faithful to the noble thought, which animated, already in the time of Louis XVI, the first message of the Government of the United States, when it pledged to your heroic country an eternal friendship."!

In 1916, the French Academy, as has already been said, conferred upon Mr. and Mrs. Tuck jointly the Prix de Vertu. The presiding officer of the Academy then spoke of them as "those two Americans for whom France is a second and dearly loved country, and who for thirty years have done good here without ostentation, without advertising, without seeking honors." In 1926, both their names went up upon the great marble tablet in the Louvre, among the names of generous donors to the national museums of France. The next year, tribute celestial in the midst of tributes terrestrial. At a meeting of the Academy of Sciences, Madame Flammarion, widow of the famous Camille Flammarion and herself an astronomer, announced the discovery of a new planet, which she had christened Tuckia. And there were tokens of gratitude in the form of medals—the medal, one to Mrs. Tuck and one to Mr. Tuck, of the National Museums of France; the Century Medal of the Banque de France; the Medal of the Historic Monuments of France; and the large gold medal of the Ville de Paris.

Rueil-Malmaison did not forget its best friends. Square Tuck and Avenue Tuck-Stell were named in their honor. Its Municipal Council, declaring that the Commune's gratitude for their inexhaustible kindnesses was profound and that the town's memory of them would be imperishable, made them honorary citizens, and announced that a gold medal would be struck in their honor in 1932.

Last, but not least, there are the tributes from the Legion of Honor, the order founded by Napoleon for the recognition of distinguished service to France. Made Chevalier of the order in 1906, Mr. Tuck was promoted regularly, becoming successively Officier, Commandeur, and Grand Officier. Then, came the crowning honor, the highest France can confer upon a private citizen. In 1929 he was made Grand' Croix, a decoration that has been conferred upon only ten other Americans since America, was a nation. In the midst of this heavy shower of honors, Mr. Tuck continued the even tenor of his way, pre-occupied with things he was doing or planning to do.

This sketch may conclude with the thought of Edward Tuck, now in the tranquil evening of his life, accompanied by memories of a dear companion of the past and of good deeds done, cheered by the affection of a host of friends, finding still in his pilgrimage a tempered happiness, and lending still—and with pleasurea helping hand to fellow pilgrims in need of aid.

BRONZE HAUT-RELIEF AT THE MAISON DES NATIONS AMERICAINES, PARIS

JULIA STELL TUCK1850-1928 Wife of Edward Tuck, Co-worker of good deeds, Officer de la Legion d'Honneur

THE HIRED MAN Taken at Bois-Preau, the estate adjoining Vert-Mont

AT THE PETIT PALAIS Beauvais tapestry and carved tapestry-covered seat, in the Edward Tuck collection

AT VERT-MONT Mr. Tuck in the salon of his chateau. Mr. and Mrs. Tuck are shown together in the photograph on the table

CHATEAU DE VERT-MONT The country home near Paris

Ambulances ofHopital Stellat Vert-Montin war time

Concert at Vert-Mont for the woundedof Hopital Stell, 1916

VIEW OF THE "GRAND QALEBIE," PETIT PALAISShowing several of the priceless art treasures donated by Edward Tuck to the French people

MR. AND MRS. TUCK Taken some years before Mrs. Tuck's death in 1928

BEAUTIFUL ESTATE Showing pool and gardens at Vert-Mont

COMFORTS OF HOME Visitors are shown this spring on the Vert-Mont estate, whimsically christened "American Bar"

OPENING THE TTJCK ROOM Petit Palais collection formally dedicated. Former President Doumer and Mr. Tuck are shown in center

LA BELLE JARDINIERE BY BOUCHER A treasure of the Tuck collection in the Petit Palais

IN THE HALL OF CHINESE PORCELAINSTuck collection, Petit Palais Galleries, Paris

A DISTINGUISHED FRANCO-AMERICAN ENTENTE EEADLNG FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: GENERAL PERSHING, GENERAL GODNAUD, SENATOR EDGE, MR. EDWARD TUCK, M. TARDIEU, M. CHARLES DUMONT, M. BRLAND, M. LAVAL. AND SECRETARY STIMSON AT THE AMERICAN EMBASSY IN PARIS

NEW HAMPSHIRE HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Concord Foundation established and housed by Mr. and Mrs. Tuck

* Dartmouth College; Sketches of the Class of 1862. By Horace Stuart Cummings, Washington, D. C., 1909.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Greatest Benefactor

June 1932 By Russell R. Larmon -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1932 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

June 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Sports

SportsIron Man

June 1932 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

June 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

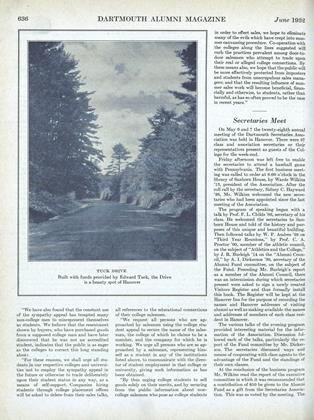

ArticleSecretaries Meet

June 1932