Doctors increasingly need the liberal arts.

THE GREATEST PROBLEMS facing the practice of medicine and medical education can be summed up in two important questions. First, how can we preserve the highest possible standards of health care when physicians and patients may gradually be losing some of their authority to make vital decisions? Second, how should we educate future physicians to function in the new and evolving environment of managed care and health-care reform?

We are well aware of the economic pressures to increase the number of primary-care physicians and to reduce the number of specialists and subspecialists. We are also aware of the reductions in support for graduate medical education, clinical training, and basic researchchanges that have occurred as federal funding authorities have sought to control costs at teaching hospitals.

Once we recognize the growing extent to which economic concerns now encroach upon scientific and educational goals in the practice and teaching of medicine, we begin to appreciate the pertinence that many other disciplines have to medical education. As new economics and new technologies reshape the practice and possibilities of medicine, the field of medical ethics necessarily commands a more central role in medical education. And not only ethics, but many other disciplines in the social sciences and humanities—psychology, sociology, history, anthropology— increasingly assert their relevance.

Yet there must surely be a temptation to avoid the pressure of dealing with so manydifferent disciplines by maintaining, rather than broadening, the current scope of medical education. As former Harvard president Derek Bok wrote in 1983, "It is hard enough to cope with the mounting complexity of the biosciences without having to take account of computers, decision trees, health care regulations, ethical constraints, and the vagaries of patient psychology."

But such a narrow definition of the physician's role, even if its stated purpose is to maintain professional autonomy, in the end would clearly compromise that autonomy by ceding authority to bureaucrats and technocrats. Physicians would be consulted principally for their "scientific" opinions, and fundamental decisions concerning patient care and research—often life-and-death decisions—would be left to others: employers, managed-care bureaucrats, benefits administrators, and government officials. If physicians are to be in a position to make their voices appropriately heard, medical education must broaden its conception of the physician's role.

For these reasons, it is essential that medical education, as an academic discipline, conceive of itself as a form of liberal education. The purpose of medical education is to train men and women in the art of healing and caring. But to heal and to care rethan technical skill; they require a rich understanding of human beings, an idealistic engagement with values, and an exposure to the humane lessons of the social sciences and the humanities, not merely as "window dressing" but as respected parts of the curriculum. At a time when patients are increasingly worried that their best interests may be sacrificed to the imperatives of cost-cutting, the broader perspective that the liberal arts provide becomes especially critical.

the liberal arts more and more if they are to strike a balance between compelling social forces and human will. It will be incumbent upon physicians to call upon the values of a liberal education in shaping medicine's agenda in the next century, in making their decisions with professional integrity, and in explaining with compassion those decisions to their patients.

Medical schools, it should be said, have an important influence on undergraduate education, not least in their admissions policies. In recent years, medical schools have sent gratifying signals that they no longer favor only those applicants who have followed a strict premed course of study, and that they especially welcome applicants who have prepared themselves broadly in the liberal arts.

Medical schools have also sent gratifying signals of their commitment to diversity, reflecting their belief that a diverse student body provides an education in empathy that is essential for establishing compassionate physician-patient relationships. However, African Americans and members of other minority groups remain under-represented in the pool of medical school applicants. And that is why medical schools must continue to make known to prospective applicants their strong interest in training a diverse medical profession to provide care for a diverse society.

The successful recruitment of minority medical students will require sustained efforts at all levels of education, as it will also require continued experimentation with intervention programs among high school and college students. These efforts are especially necessary at a time when some seek to dismantle affirmative action programs in this country.

It is these interrelated concerns—the threat that managed care poses for medical education and basic research, the relevance of ethics and liberal education to the study of medicine, and the necessity of diversity in medical school student bodies—that present some of the greatest challenges, as well as some of the greatest opportunities for progress, today. I am confident that as Dartmouth Medical School ventures forth into its third century, it will remain an integral part of—and benefit from—Dartmouth's liberal arts environment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

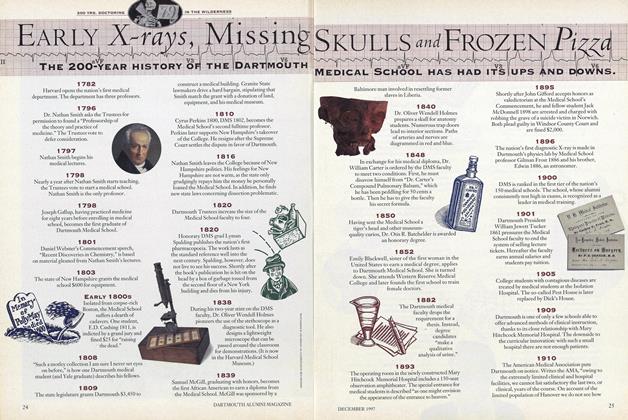

FeatureEarly X-rays, Missing Skulls and Frozen Pizza

December 1997 -

Cover Story

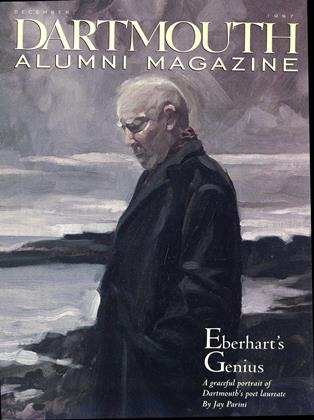

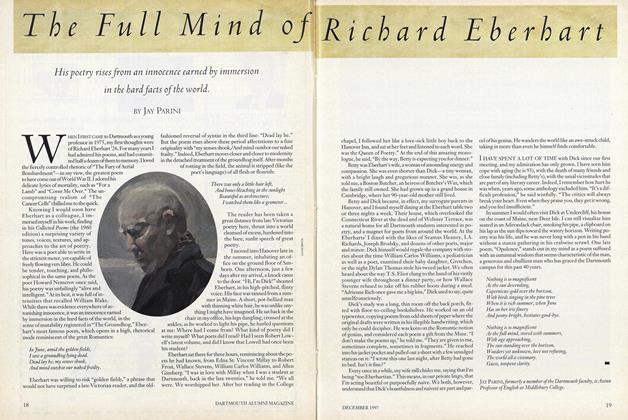

Cover StoryThe Full Mind of Richard Eberhart

December 1997 By Jay Parini -

Feature

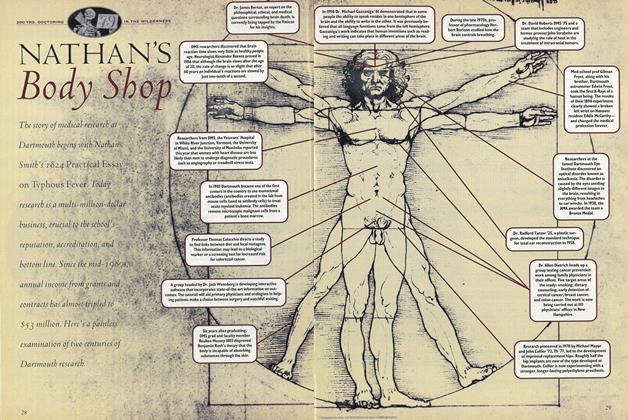

FeatureNathan's Body Shop

December 1997 -

Feature

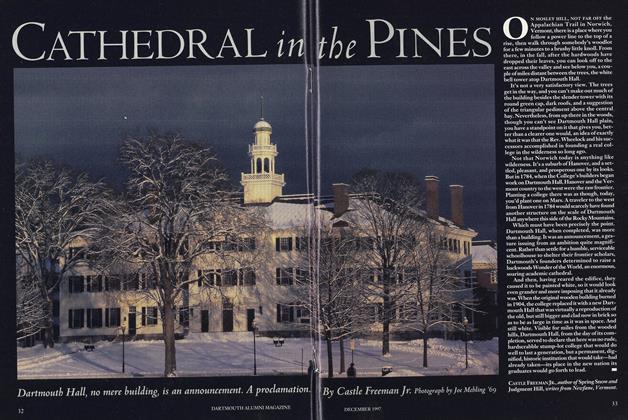

FeatureCathedral in THE PINES

December 1997 By Castle Freeman Jr. -

Feature

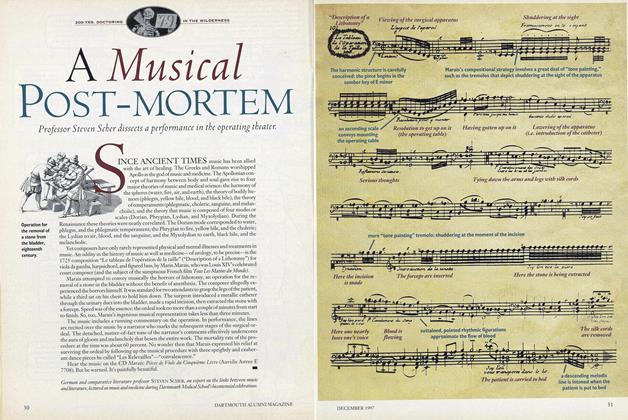

FeatureA Musical Post-Mortem

December 1997 -

Feature

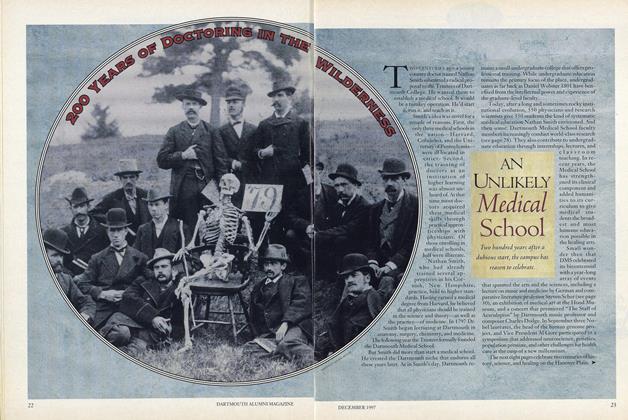

FeatureAn Uulikely Medical School

December 1997

James O. Freedman

-

Cover Story

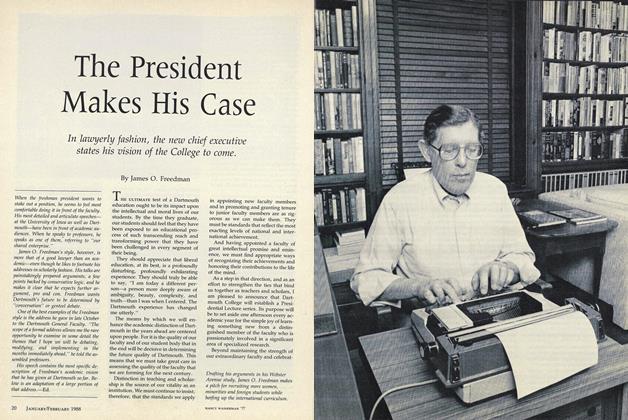

Cover StoryThe President Makes His Case

FEBRUARY • 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleCompared to What

June 1992 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleLessons of the Law

NOVEMBER 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe New Great Issues

OCTOBER 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Education Gap

January 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleStaying Out of the Groove

SEPTEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman