Homeless Ethics

In "The Faces of Homelessness" (Lexington Books), Marjorie Hope and James Young '40 assert that many homeless people share the Puritan belief in the value of work and money. Here the authors describe a "bag lady" in New York's Port Authority Bus Terminal. She confides that the police are after her because she does not have a bus ticket.

When we sympathized with her, and said we considered that unjust, her eyes widened in surprise. Almost belligerently, she declared that this was the way it should be. "You pay for your ticket, you can sit in this place. You don't pay, you got no right to be here."

The Battle of Van Heusen

The latest fiction by attorney Bruce Ducker '60, "Failure at the MissionTrust" (Freundlich Books), is subtitled "A Novel About the Morality ofBanks." The narrator, Howard Adler, finds himself in the midst of amerger of two banks. Employees from one wear white shirts; those inthe other, blue. Seeking to describe the result, Adler turns to the languageof warfare.

When I was in the fifth grade, I sat for the full year under a print called the Battle of Poltava. I loved that painting. It was a giant battle panorama, with hundreds of figures. I don't know who did it, but I used to stare at it for hours. I didn't learn much else in the fifth grade. What had happened was this: Charles XII, king of Sweden, decided to invade Russia. He set siege to the city of Poltava, in the Ukraine. But he hadn't counted noses. The czar had an army that outnumbered his three to one, and he sent them to Poltava and kicked the stuffing out of the invaders. Sweden hasn't been heard from since. In the painting, the Russians wear white tunics and the Swedes wear red with white sashes. You have to wear different colored shirts in hand-to-hand combat in order to know who the enemy is. I studied that picture for hours, looking for some smart Swede off in a corner, changing shirts.

Recognizing Sin

Dinesh D'Souza '83, managing editor of the Heritage Foundation'sjournal "Policy Review," feels that Saint Augustine's "Confessions"has relevance to the modern reader. This is from "The Catholic Classics(Our Sunday Visitor).

To the modern reader, Augustine's self incrimination for his sins seems a bit excessive. He is constantly beating his breast over a petty theft during his childhood or for taking a mistress. Although we do not condone stealing or engaging in illicit sexual activity, such things are commonplace in our time, and we have a hard time getting worked up about them. But does that reflect something about Augustine or about ourselves? The value of the Confessions today is that it illuminates the meaning and omnipresence of sin when so many of us have ceased to take it seriously. Watching Augustine agonize over his lust and avarice, we are tempted to sneer at his lack of sophistication or chuckle at his righteousness, and yet there is a strange glimmer in our soulsthe glimmer of recognition of the fall of man, of our own sins, of our need for redemption, of the saving grace of Jesus Christ.

Schooling an Empire

London's Westminster school launched the education of some of theeighteenth century's finest wits including William Cowper, CharlesChurchill and Robert Lloyd, who helped found a brilliant literary society.In "The Nonsense Club" (Oxford University Press), Lance Bertelsen'69 describes the school's place in the midst of a fast-changing England.

Surrounded by neighborhoods ranging from town houses to tenements, open to a massive literary stimulus in the form of the daily, weekly, and monthly productions of the London press, Westminster School represented a kind of crucible for the complex negotiations of eighteenth-century English society. A heterogeneous mixture of boys ranging from the sons of lords to the sons of apothecaries, Westminster students experienced with unique immediacy the rituals of power and the counter-rituals of irreverence, the paradoxes of birth and rank within the dominant ideology of liberty, and, particularly for boys of the middling sort, the confusing pressures of social aspiration and traditional deference in a society whose people were becoming more so phisticated as the circle of real power became more exclusive.

Pre-Scarsdale Majors

After graduating from Dartmouth in 1968, Lewin Joel migrated fromaccounting to law to modeling to teaching. In his first novel, "Beauty"(Simon and Schuster), Joel's protagonist, Lynell Alan, thinks back onthe College during the late 1960s and early '70s.

For all of their pride in their deserved reputation as animals, most Dartmouth men were intensely interested in something: maybe it was only women and beer, maybe physics and chemistry, or track and football. Most at least had something, and most had goals, dreams. They wanted to be doctors, lawyers, or bankers. They wanted to find "Miss Right" ("a gorgeous nympho"), eventually get married and have a family, live in Scarsdale or Grosse Point or Westport.

From "The Faces of Homelessness"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

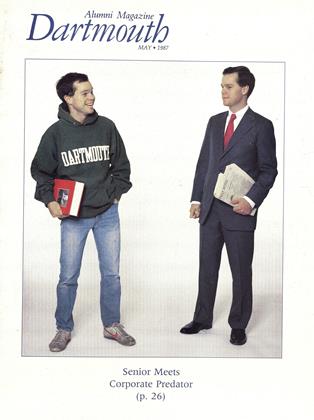

Cover Story

Cover StoryLooking for Mr. Goodjob

May 1987 By Jock McDonald '87 -

Feature

FeatureA Spanish Galleon's Real Treasure

May 1987 By R. Duncan Mathewson III '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Uncompetitive Society

May 1987 By Richard D. Lamm -

Feature

FeatureThe Official Dartmouth Reunion Guide to Greenspeak

May 1987 -

Sports

SportsA Fast-Balling Junior Mulls Going Pro

May 1987 By Jim Needham -

Article

ArticleStan Brakhage '55: "The Picasso of Cinema"

May 1987 By Lee Michaelides