But September faded into October; leaves had but few traces of green, and freshmen had already learned to pick their way from dormitory rooms to the reserve desk in the library. The first days of October were milestones in the lives of many sophomores. Those were the days of fraternity rushing, pledging, papersigning and informal initiations. One man measured the length of Main Street with a dead fish; another wandered through the outlying towns looking for a lighthouse. All were building up to the formal initiations and the day when they could learn a grip, attend meetings, and buy a sister pin for the girl back home. Class attendance was punctuated by football weekends, Monday morning quarterbacking, and skepticism at Richards Vidmer's inevitable selection of Dartmouth at the losing end of every game. But around all the football talk and cutting through the clear, crisp air of autumn, there was the dark cloud of war in Europe. Professors could point to the continent as illustration of their class discussions. A Dartmouth undergraduate was called to join the Canadian Royal Air Force—others were expected to follow—and war came closer than ever to home. Everyone declared himself against going to war. Polls indicated that Dartmouth College would not fight under any circumstance, except that of invasion of the United States. But no one was sure that America could stay out of it. One question was on everyone's lips. "Is the world of 1939 too closely connected to allow any great power to remain neutral?" Everyone prayed that it wasn't.

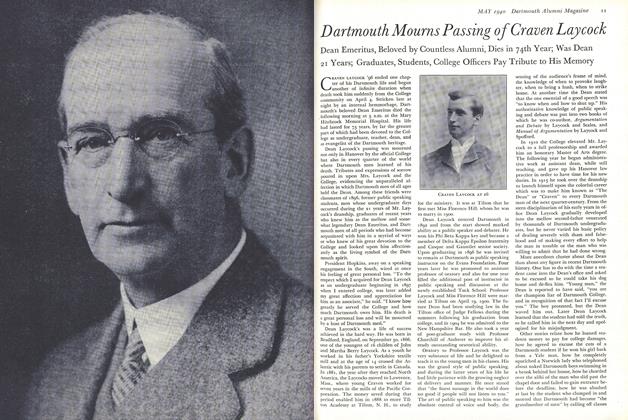

By November all the leaves were off the trees and a chill wind blew across the plains, whipping the fallen leaves into floating tunnels. The Dartmouth passed through its first one hundred years as a college newspaper, gave a banquet, and invited past editors of the paper to attend. Editors were assured by three out of every five people who passed them on the street that "the first hundred years are the hardest" and learned that the hundredth year was no cinch. A houseparty came in with the Cornell game, lasted two and a half days and died a natural, and not altogether painful, death. It was the month of Dartmouth Night, the night when members of the Dartmouth family met in Webster Hall and in Dartmouth clubs strung out across the forty-eight states. It was made even more important because it put Dean Craven Laycock on the rostrum from which he addressed the College he had so long served with full and unselfish devotion; for many, it was the last time they were to hear the twinkling-eyed Dartmouth figure speak. It was the last time they were to hear him stand up in front of the student body and introduce himself with the words "Good to see you." It was good to see him.

Few will forget that November was the month in which Earl Browder was invited to speak before a Dartmouth audience by a small group of students. The groups who asked him will never forget it; the groups who stood in the middle and watched the verbal shots zoom over their heads will never forget; and the groups who balked at the proposal couldn't possibly forget it, try as hard as they might. There is always someone standing around who remembers. Harvard started the ball rolling; then Dartmouth started its own. First the Communist leader was coming, then he wasn't. The C.0.5.0. put the clincher on it and Browder was out. It made for good discussion fodder and developed more streetcorner orators and social thinkers, in the most conservative sense of the word, than anything that has hit the campus since the crusade for shorts back in 1929.

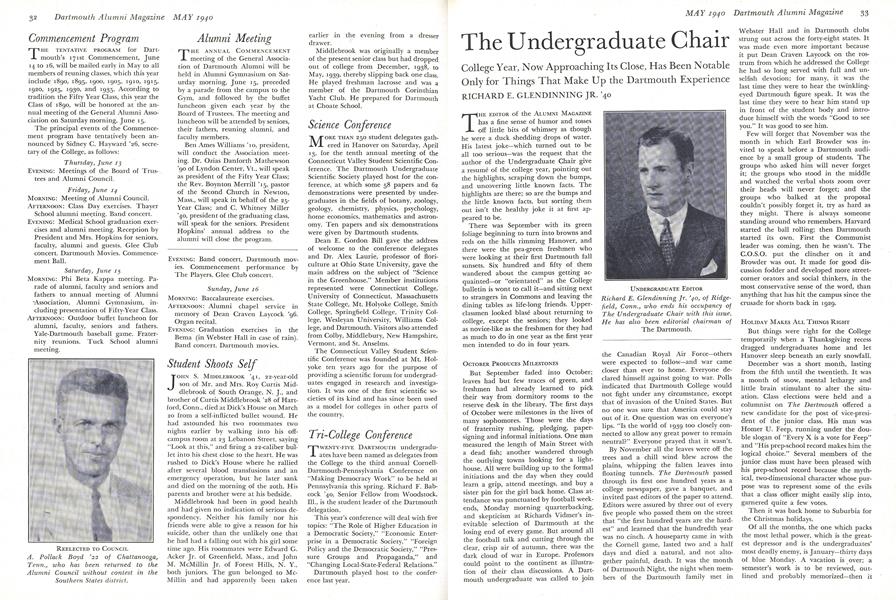

UNDERGRADUATE EDITOR Richard E. Glendinning Jr. '40, of Ridgefield, Conn., who ends his occupancy ofThe Undergraduate Chair with this issue.He has also been editorial chairman of The Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Mourns Passing of Craven Lay cock

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleI Found Seven Latinos

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleJohn M. Mecklin, Teacher

May 1940 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

May 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN, RUSSELL B. LIVERMORE -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

May 1940 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, H. WARREN WILSON

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND THE PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN

December, 1912 -

Article

ArticleMessages Received on Dartmouth Night

March 1936 -

Article

ArticleDemocrats: Young and Old.

APRIL 1966 -

Article

ArticleStriking a Note

July/August 2012 -

Article

Article'25 Committee Reports

October 1945 By Lloyd D. Brace, Chairman. -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

June 1934 By S. C.H.