For Thirty-Two Years Dartmouth Track Has Been Coached by a Champion and Maker of Champions

THIRTY-ONE YEARS AGO this month, a young man working in one of the New York stock exchange houses was asked to come to Dartmouth to coach track. He had an imposing record of competitive track athletics behind him, a case full of medals and cups, and a string of world records almost as long as the pair of legs which had propelled him over the cinder tracks of two continents faster than anyone had ever run before. The coaching job was a completely new type of work for him. He was doing all right in the brokerage business and his prospects were good. He had lived in New York all his life. His friends were there. He was a member of the New York Athletic Club, where he had made many friends. He had never been to Hanover and wasn't exactly sure where it was, although he had heard a great deal about Dartmouth athletics during his own competitive career. But he decided to give the new job a try and took a train for the North Country. He landed on Hanover Plain in the dead of winter, 1910. He is still there.

In his thirty-one years with the College, Harry Hillman has seen more than seven college generations come and go. He has coached intercollegiate champions galore, has prepared more than one Dartmouth track man for the Olympic games, and has seen his most prized pupil crowned Olympic champion. He has also had his lean years, when Dartmouth brought up the end of the procession in the Quadrangular and the Heptagonal games and squeezed through with a meager two points in the indoor intercollegiates and no points at all in the outdoor intercollegiates. But through all those years, Harry has kept trying, doing his best with often undistinguished material, nursing his star milers and high jumpers through pulled tendons and probation, and sending his teams down the Connecticut valley in the spring before the track was completely dry and before they had been out-of-doors for a single good workout. Far and away the oldest coach in the College in point of active service, Harry is also one of its finest gentlemen and sportsmen.

For almost every year hope springs anew in his breast. He hears of a crack schoolboy hurdler from California who has somehow eluded the institutions of higher learning on the Pacific Coast and has signified his intention of entering Dartmouth. Or he learns of a young giant from one of the eastern prep schools who is reputed to have thrown the la-pound shot more than fifty feet with no form at all in his sixteenth year. Or an alumnus from Arlington writes him about the wonderful schoolboy middle-distance runner who won every interscholastic in his senior year in high school and has just been accepted for the next entering class. These boys are reputedly not only able performers in the high hurdles, weights, and middle distances but are also straight A students for four years in high school. Such news warms the cockles of Harry's heart. He already has visions of the sophomore hurdler flashing over the barriers to win the Heptagonal meet in record time. He conjures up in his mind's eye a delightful picture of a two hundred and twenty pound youngster tossing the 16-pound shot out of the lot in the outdoor IC4A games. And the thought of the middle distance runner striding in three yards ahead of the field in the intercollegiate quarter mile and then anchoring a record-breaking mile relay team is almost too good to be true.

As a matter of fact, it usually is too good to be true. The hurdler from California gets a scholarship and comes to Dartmouth all right, only to pull a tendon in his freshman year which removes him from intercollegiate competition for the rest of his career. The unhappy boy spends most of his next four years futilely baking and roasting his leg in the various elaborate contrivances for that purpose which fill the training room in the Davis Field House. The weight thrower looks like one of the best shot and discus prospects in years. Harry is sure that, if he can only work with him regularly for a few months, he can get him up to 48 or 50 feet in the 16-pound shot and maybe higher. The only trouble is that Harry never sees the boy in a track suit. He goes out for football in the fall of his freshman year. He is a whale of a tackle and the football coaches smile delightedly as they think of his 220 pounds filling one side of the green line for the next three years. When the football season is over, the boy is considerably behind in his books. He has to study pretty hard that winter and is just getting under way with his work when the time comes to go out for spring football. Harry knows as well as anybody that football has to pay the way for all the other sports and naturally gets the call. He is a good sport about it. But there goes his weight thrower. And what about the sensational middle distance runner from greater Boston? He runs a 4:20 mile his freshman year and looks wonderful. But he spends his sophomore year on probation and finally drops out of school. (There are naturally no indivious implications toward the scholarship of greater Boston boys in this example. This could, and does, happen to anyone from any place.)

CURRENT PROSPECTS

At the present time, Harry is nursing along one of the greatest middle distance prospects that ever came to Dartmouth. The boy's name is Don Burnham and his home is in Lebanon. His father is Doctor Arthur W. Burnham, who graduated from Dartmouth in 1912 and the Dartmouth Medical School in 1914. Harry has had his eye on the boy ever since he was a freshm an in Lebanon High School. Many great schoolboy runners are burned out in prep school because their coaches enter them in everything from the hundred-yard dash through the half mile. Harry has taken no chances with this boy, but has kept in touch with his father and his coach all through his four years in high schoolwatching, encouraging, and above all allowing him to run only one or two races in a single afternoon. Don has already been elected captain of the 1944 crosscountry team, where he should further build up his resistence for the grueling pace of intercollegiate competition. So Harry is keeping his fingers crossed. The boy is a brilliant student, so there is no possibility of ineligibility. He was awarded the New Hampshire scholarship on the basis of his fine record in high school. The only thing that might happen to him is to pull a tendon. So cross your fingers, too, you old-time Dartmouth track men. Harry has another potential champion on the way.

But life at Dartmouth hasn't been all headaches and heartaches for Harry Hillman. Not by any means. Some of the star prep school high jumpers, hurdlers, pole vaulters, and quarter-milers have steadily improved under his training. They have managed to avoid pulled tendons, charley horses, and that old devil probation and have been a credit to themselves, to Harry, and to the College. They have come through in the dual meets, the Quadrangular, the Heptagonal, and the intercollegiates. Other boys with less natural ability have plugged along for four years, not setting the cinders on fire, perhaps getting their letter and perhaps not, but making the trips and learning something from Harry. And not only about track. About sportsmanship, about trying as hard as you can, about finishing the race even though you are hopelessly behind and your heart is pounding and your legs feel like jelly and you would rather lie down and die than dive for that last hurdlethose are some of the things that almost eight generations of Dartmouth men have learned from Harry Hillman.

There is another coaching experience which Harry enjoys more than any of the others. That is to take a boy who has never run, jumped, or thrown a javelin in his life before he came to college and develop him into a great track man. Harry doesn't believe in miracles or silk purses out of sow's ears and this doesn't happen very often. But it still happens. Every year a motley assortment of gangling or pudgy youngsters come out for track, boys who have never done anything more athletic in high school than play ping-pong or go to the Junior Prom. They talk to Harry or to Ellie Noyes, the able freshman track coach and Harry's right hand man. These aspiring freshmen are never summarily told that they can never do anything in track and that they had better devote their talents, if any, to the business board of The Dartmouth or the technical staff of the Players. Rather are they encouraged to come out and try to do the particular event for which they seem best suited. The varied character of track athletics is such that many different types of ability and physique can be used. Youngsters who look so frail that they might collapse at the end of fifty yards may develop into cross-country runners, capable of pounding endlessly up and down hills without even drawing a deep breath. Other boys who look too fat or muscle-bound to tie their own shoe laces may have just the proper coordination to become javelin throwers and shot putters. The chances of any boy becoming a champion in any of these events are, of course, problematical, to say the least. But miracles sometimes happen. And Harry is the man to make them happen if it is humanly possible to do so.

EARLY LIFE IN NEW YORK

Harry Livingston Hillman was born in Brooklyn, New York, on September 8, 1881. He attended Brooklyn High School for 4 years, after which he went into business. His first job was wi th Scribner's Magazine, after which he entered the world of banking and finance which was to occupy him until he came to Dartmouth. He worked for the National Bank of North America for several years and was in line for a department headship when that imposingsounding institution collapsed in the panic of 1907. He then went into Wall Street, where he was employed by a stock brokerage concern for several years. When he was ready to come to Dartmouth in 1910, he was given a farewell banquet and a solid silver service set by his friends in business and the New York Athletic Club. On January 10, 1941, Harry will celebrate the beginning of his thirty-second year in the service of the College.

On May 2, 1908, Miss Hazel Quantin became Mrs. Hillman. They have two fine children, Madeleine and Harold. Madeleine is studying art in Boston and co bines these artistic talents with a very solid golf game. Of Harold more anon.

Harry looks back upon his ten years in the banking and brokerage business with affectionate nostalgia. But the most significant events in his life have taken place on and about the cinder track, where he has been carrying on for almost forty years, man and boy. Early in his business career, he joined the Thirteenth Regiment of Coast Artillery of the New York National Guard. He served in the regiment for ten years and came out as a first lieutenant. This was the start of his track career and he began to practice running and hurdling several nights a week after banking hours. His competitive activities in the metropolitan meets brought him to the attention of the Knickerbocker Athletic Club and afterward of the New York Athletic Club. He is a life member of the latter organization in recognition of the sterling services rendered in his early manhood.

By the time the Olympic Games of 1904 rolled around, Harry was the leading hurdler in the United States and indeed, as it proved, the world. In those games, he showed his heels to the best athletes of all nations in no less than three events—the 400-metre flat, the 400-metre hurdles, and the 200-metre low hurdles. Since the revival of the Games, America has had very few athletes who were able to win three different events. No nation, with the possible exception of incredible little Finland, has turned out many triple Olympians. Three Olympic records were set that year by the young New York bank clerk, some of which were to remain on the books for many years. Harry's St. Louis record in the 200-metre hurdles still stands, not only because of the superlatively fast time but also because the event was discontinued in subsequent games.

Two years later, Harry was again chosen for the American Olympic team, this time to compete in Athens, the homeland of the original Games. In those days, American Olympic teams were not the small armies which they have subsequently become. Some 35 athletes represented the United States in 1906 and Harry has a picture of them, lined up in front of a large body of water, presumably the Aegean Sea. On the boat going to Athens, in mid-Atlantic, Harry was temporarily incapacitated by an improbable accident which he succinctly describes as "being hit by a wave." Details are lacking as to where and under exactly what circumstances this accident took place, but in any event it was sufficient to put him out of competition for the duration of the trip.

Harry's third Olympic competition came in London in 1908 (they had the games oftener in those years), when he ran second in the 400-metre hurdle race. The race was won by a friend of Harry's whom he had persuaded to try the event. Competition was more informal then and the American athletes perforce did not take themselves as seriously as they do now.

These three Olympic trips were the high points in Harry's competitive career. He continued running for some years after the London games and added to his already formidable list of metropolitan, American, Canadian, French, and miscellaneous military records. The latter were established when Harry was a member of the Coast Artillery. In the World War, he served in the Air Service as a first lieutenant. With Lawson Robertson, longtime track coach at Pennsylvania, Harry established the most bizarre of all his track records—the three-legged race. This curious event is performed by two runners who have their inside legs firmly strapped together and who perform thus literally on three instead of the customary four legs. Harry and Lawson were terrific in this race. They managed to ring up world rec- ords for the following distances—4o-50-60- 70-80-90-100-110-120 yards—which presum- ably are still on the books. The most incredible feat of this pair of three-legged partners was to negotiate the 100-yard dash in an even 11 seconds. When you remember that ten seconds for that event is considered excellent time for a sprinter running in the manner to which human beings have been accustomed for some time, you will appreciate the coordination involved in this performance. Indeed, that indefatigable collector of anthropological oddities, Robert E. (Believe-It-Or-Not) Ripley was so struck by this joint record that he incorporated it in his first cartoon and afterward in his book.

Sometime in his post-Olympic competit ive career, Harry was chosen to go to New Zealand, Australia, and Japan for a six month junket, during which time the touring athletes were supposed to compete with the local talent in the various countries. Unfortunately for his acquainta nceship with the lands "down under," Harry still found it necessary to work for a living. The trip had to be passed up.

Harry has had two careers in athletics, either of which would be enough for the average man. When his competitive days were over, he was able to take up the ever-fascinating task of teaching succeeding generations of college boys the tricks he had so laboriously learned for himself. In addition to his work at Dartmouth, which we shall discuss in detail below, he has served as associate coach in charge of the hurdlers on three Olympic teamsP aris in 1924, Amsterdam in 1928, and Los Angeles in 1932. He also served as trainer on the American Davis Cup tennis team in 1935 and spent the summer with the team abroad. Harry looks back upon the Olympic coaching trips as pleasant interludes in the midst of the years in Hanover. Coaching Olympic teams in these days is not a very arduous job. If a boy is good enough to make the team, he already knows all there is to know about his speciality. Harry wisely realized that any attempt to do anything drastic about the hurdling form of an Olympic runner in the brief weeks between the time the team was selected and the time they competed would be somewhat gratuitous, not to say disastrous. His chief job was to keep his high-strung charges in good spirits and above all to keep them from going stale before the final crucial test. The phenomenal success of the American hurdlers in these recent games may very well be due in part to this judicious Hillman policy of laissez faire.

FATHER AND SON

.While we are on the subject of Olympic teams, it is notable that Harry's athle tic career has another unique element —well, almost unique. In the history of modern Olympic sport there have been, as far as our researches can determine, only two instances of father and son competing on American teams—not, we hasten to add, on the same teams. The first was the father-son combination of Joe and Ray Ruddy, who were swimmers on two generations of Olympic teams. The other was Harry Hillman and his son, Harold. Harry was a three-time Olympian and Harold was chosen for the American ski team which would have competed last winter, barring the interference of World War 11. Harold is an excellent all-round athlete, playing golf in the low 70's in the summer and doing everything that has ever been done (and many things that haven't) on skis every winter. The only thing that Harold has to show for his Olympic prowess is a sweater and a certificate testifying that he made the team. But there is no mistake about his doing that.

GOLFING AMBITIONS

We have been nosing about the periphery of Harry's amazingly versatile career too long before getting down to cases and the main point at issue, namely, his work as coach of track at Dartmouth these thirty-one years. It is characteristic of Harry's modesty that he should want to talk more about his golf game than about all of his services to the College in this period. He will celebrate his sixtieth birthday this year and is very anxious to signal that event by breaking 80 on the Hanover course. In the interest of accurate reporting, we must regretfully inform our readers that he has not yet done so, even though he has made two different holes in one. But 80 remains unbroken and Harry says the only way he can win a golf game any more is to talk his opponent out of it.

In his three decades with the College, Harry has left the mark of his careful coaching and his personality upon almost eight generations of Dartmouth men, as well as upon followers of track and field sports all over the country. There is no question of his superlative skill as a coach. Men in a position to know have said that, given the material and the weather the big-time track coaches have on the west coast, Harry could turn out teams that would be the equal of Southern California and Stanford. In that connection, although most people don't know it, Harry was actually offered a job at one of the far-westem institutions some years ago. Given that situation, he could unquestionably have turned out teams which would have come east and run away with the outdoor intercollegiates with the same ridiculous ease as the coast teams have evidenced in recent years. But Harry liked it at Dartmouth.

And he has done all right by Dartmouth, any way you look at it. Character building is fun and it is fun to take gangling kids who never participated in athletics before and make good high jumpers and hurdlers out of them. But it's also fun to turn out the champions—to watch your boys hitting the tape first in the intercollegiates, to have them throw the shot and the discus farther than anyone else in the east can throw them, and to watch them jump farther and higher than the boys from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Harry has had his share of that too. A good many champions have worn the green during his years at Dartmouth.

Here is a partial list of the outdoor intercollegiate champions who have carried Dartmouth to glory on the track and in the field in the past three decades. Many others not mentioned have won indoor titles. Mind you, this is a partial list and includes only those men who have won outdoor ICAAAA titles: Bud Whitney 'l5 in shot, Mark Wright 'l3 in the pole vault, Russ Palmer 'lO in the high jump, Tony Geniawicz '37 in the shot (twice), Roy Brown '33 in the high jump, Zack Jordan '2O in the pole vault, Jack Donovan '3B in both high and low hurdles, Earl Thomson '22 (remember him?) in both high and low hurdles, Gus Braun 'l5 in the high hurdles, Monty Wells '2B in the high hurdles (notice all the hurdlers), Phil Nordell 'l6 in the broad jump, Harry Worthington 'l7 also in the broad jump, Carl Buck 'l3 in the pole vault, Jake Enright 'l3 in the high jump, Bill Marden 'll in the hammer throw, Mel Metcalf '32 in the javelin, Jake Shelburne 'l9 in the shot, and Tom Maynard '29 in the high jump. That's quite a record for you, what with the long cold winters, and one thing and another.

Seven members of this group were also competitors on various American Olympic teams. Bud Whitney, Mark Wright, Jake Enright, Roy Brown, Harry Worthington, Mel Metcalf, and finally Earl Thomson, have all worn the red, white, and blue emblems on their jerseys. The most famous of the Dartmouth Olympians was unquestionably Tommy Thomson, who topped the high timbers in world record time in the 1920 games. He was competing for Canada in those games and his victory was chalked up to the British Empire. But a lot of the glory went to Dartmouth and to Harry Hillman for turning this big, raw-boned speedster into the superlative hurdler he became. To those of us who were undergraduates in the early '2o's, the story of Thomson clipping dimes from high hurdles without breaking his stride had already become a legend. This biggest and best of all the big green timber toppers has been carrying on as coach of track at Annapolis for many years. He and Harry have a good visit every year at the outdoor intercollegiates.

In recent years, Dartmouth track and its genial mentor have been in the limelight for another reason. The fabulous records established on the famed indoor board track are known to every track fan in the country. This springy board surface, encircling the cavernous lower level of the gymnasium, is the apple of Harry's eye. It has brought forth lyrical outbursts from many of the most famous distance runners of our day. The specifications and history of that oval have been described several times before in this journal, so your correspondent will content himself with pointing out that the track was Harry's idea. It was also Harry's idea to invite the great group of distance runners who have bounded about this track in the past few years faster than anyone ever ran the same distances before. Those of us who saw Glenn Cunningham turn out the famous 4:04:4 mile will never forget the thrill of the barrel-chested Kansan piling the four fastest consecutive quarter miles in history one upon the other—and finally come dashing across the finish line with the speed and stamina of a whippet tank. That was a big moment for Harry. He had said this was the fastest indoor track in the world. Nobody was going to dispute him after that.

We have been hearing a lot about sportsmanship in college athletics recently. And rightly so. Here is an incident which illustrates the sort of sportsmanship Harry practices as well as preaches. Some years ago, in one of the big indoor meets in Boston, Dartmouth had entered a pretty good relay team. In fact, the team was so good that they managed to win their race by a handsome margin. In the process of winning, however, one of the Dartmouth runners inadvertently fouled an opposing runner by jostling him during a scramble for a turn. Harry was apparently the only one on the floor who saw the foul, which was as palpable as it was unintentional. The officials didn't see it. They immediately awarded the race and the medals to the Dartmouth team as the unquestioned winner. Harry went up to the Dartmouth captain, who wasn't running in the race. He asked him if there hadn't been a foul. The boy said he didn't know, but he would ask his teammates. The boy who had committed the foul said that he might have jostled the other man illegally but he certainly hadn't done it on purpose. That was all Harry wanted to know. He reported the incident immediately to the officials, insisted upon Dartmouth forfeiting the race, and made the boys give the medals back on the spot.

CUTS HIS OWN HAIR (?)

When Harry was getting ready to come to Hanover in 1910, one of his friends in New York asked him if he had bought his pair of clippers. Harry asked him why and the friend seriously informed him that there were no barbers up there in the north woods. He would have to cut his own hair and had better buy a good pair of clippers before leaving New York. Harry thanked his friend, bought the clipp ers, and has been cutting his own hair with them ever since. At least that's his story and he will stick to it.

This tall tale is typical of the many incredible yarns that Harry will spring with a perfectly straight face and with an air of ingenuousness which completely belies the sly humor lurking behind his guileless exterior. Harry is a great joker, practical and otherwise, famed even in the Hanover community which is a fertile field for some of the most ingenious and gargantuan practical jokes ever perpetrated. Harry and Jeff Tesreau are the chief in Stigators of these whimsies, aided and abetted by Tommy Dent and Sid Hazelton. They will go to fantastic lengths to spring a sound bit of innocent chicanery upon one another. On one occasion, Jeff managed to shoot himself a deer. Harry swears that Jeff spent the day sitting on a log and smoking his pipe while the other men did the work and beat the forest in good safari style. The only one who saw a deer, however, was Jeff. The creature came loping over a hill and stopped directly in front of Tesreau on his log. All he had to do was to pick up his gun and it was all over. Jeff hung the deer in his garage and some of the boys, including Harry, planned to abduct the carcass. Some of the other conspirators turned state's evidence, however, informed Jeff of the threatened abduction, and left Harry to hold the bag. Jeff waited in the garage with a shot gun loaded with salt, ready to protect his property. The denouement of the story came when Harry, too old a hand at this sort of game not to smell a rat, himself failed to appear and left Jeff to hold the fort with saltfilled shotgun.

Jeff has another wonderful yarn to tell about his pitching days with the New York Giants. The periodic invasion of Flatbush to play the Brooklyn Dodgers has always been a trying ordeal for the New York athletes. Jeff says that every time he was called upon to pitch in Brooklyn he was subjected to insulting remarks delivered in a voice which swelled even above the stentorian chorus of the other Brooklyn fans. These remarks, directed alike at Mr. Tesreau's qualifications as a pitcher and a gentleman, did not render his pitching chores any more pleasant. With the passing of the years, Jeff no longer pitched for the Giants. He came to Hanover as coach of baseball, where he has remained ever since, turning out championship teams with gratifying regularity. His first day in town, he heard a voice in the gymnasium which brought back memories of other days. He couldn't for the life of him remember at first where he had heard that voice before. Then he remembered. Rising loud and clear over the jeers, boos, firecrackers, and cowbells of the Brooklyn crowd, he remembered this voice chanting, "Take the big fellow out. He can't pitch." Then the owner of the voice came around the corner. It was Harry. With this inauspicious beginning, a great and beautiful friendship ripened with the years. Jeff and Harry are still at it.

Other legendary stories cling like an aura about Harry's greying head. At least once every year, he sends the assistant manager of track out to find a particular variety of oil for the hammer. The boy returns in a state of great anxiety after a period of search which varies with his degree of conscientiousness and acumen to report that no such oil is to be found. On more than one occasion, Harry has been known to substitute for his opponent's golf ball a pellet made of soap during an important golf match. And the running fire of chatter with which he intersperses his own and his opponent's shots in a golf game are alone worth the price of admission.

At the present time, Harry is embarking on a new career—that of radio commentator. Sponsored by some of the local and regional merchants, he has been giving a weekly program of sport reminiscences over Station WNBX in Springfield, Vermont every Friday night. He says it's been fun, but he didn't realize you could say so much in half an hour. He also reports some very pungent comments on the content of the program and the Hillman radio delivery from the boys in Allen's drug store.

But Harry is more than a genial perpetrator of practical jokes and a delightful companion on the golf course. He is more than a coach of track and cross-country. By virtue of his thirty-odd years in the service of the College, not only as coach of track but also as trainer of twenty-two Dartmouth football teams under five different coaches, he has become a symbol of Dartmouth athletics. From the opening of college until the cross-country season subsides under a blanket of snow in late November, and from the first faint signs of melting ice on the track in the spring until the team goes to the intercollegiates the last week-end in May—rain or shine, hot or cold, still or windy—Harry stands at the north end of the outdoor track in his leather jacket vand his old baseball cap, telling the boys to use their arms, keep their knees up—and finish hard. He has seen the misty outlines of Mount Ascutney loom up beyond the south end of the track on many thousands of afternoons, as the sun and wind have added a few more wrinkles to the comers of his eyes and a few more layers of tan to his cheeks. We hope he can be out there for many thousand more afternoons.

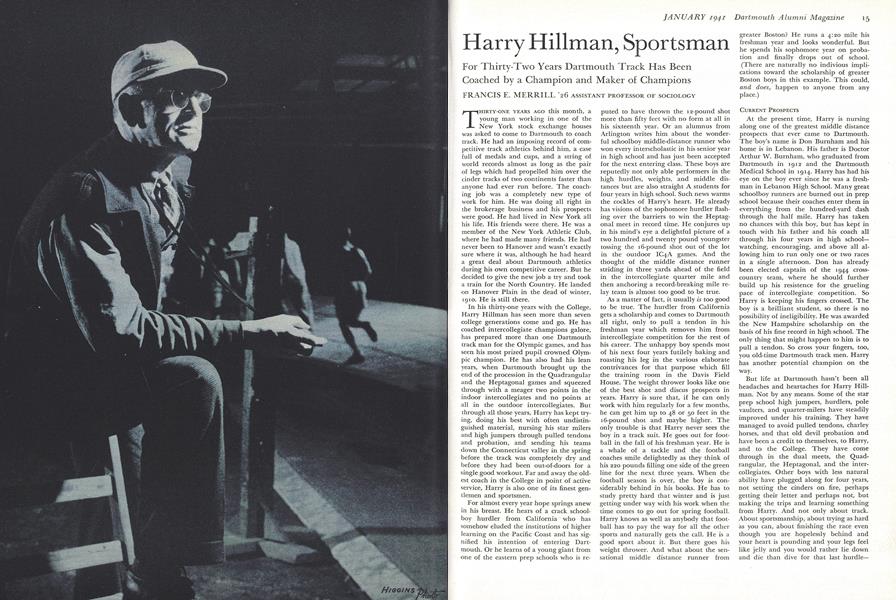

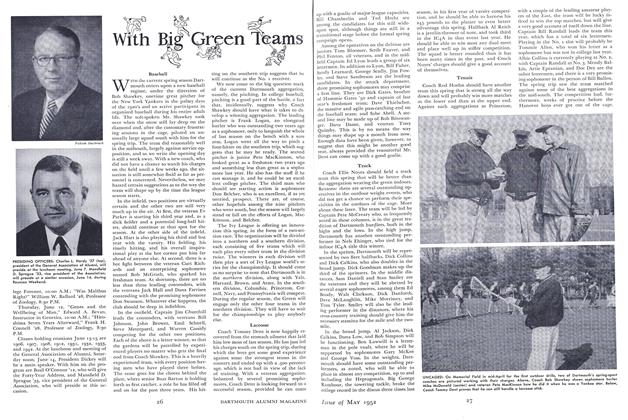

BEGINNING OF HARRY HILLMAN'S TRACK FAME WAS IN THE DOING, NOT TEACHING Left: Hillman crosses the tape to win a match race with Melvin Shepard at Celtic Park,Long Island, in 1907. Right: Hillma?i poses with Lawson Robinson, with whom he setthe existing world's record in the three-legged race.

DR. HOWARD N. ("BUSH") KINGSFORD IS AN OLD CRONY OF HILLMAN'S

COACH AND PROTEGE Hillman discusses fine points of the gamewith Don Burnham '44, promising middledistance runner.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThat Men May Understand

January 1941 By HAROLD ORDWAY RUGG '08 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

January 1941 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleALUMNI TRY THEIR WINGS

January 1941 By Everett Wood '38 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1941 By Charles Bolté '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

January 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR, ROGER C. WILDE -

Article

ArticlePreservation of Democracy

January 1941 By CLYDE C. HALL '26

FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26

-

Sports

SportsINTERLUDE

December 1944 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsTHE TACKLES

October 1948 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsLacrosse

May 1952 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Sports

SportsGolf

May 1952 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Sports

SportsRugby

June 1952 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Books

BooksHUSBANDS & WIVES: THE DYNAMICS OF MARRIED LIVING. "

January 1961 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26