Gradually during the second semester of 1914-15 Dartmouth became aware of World War I, but only gradually. There were few of us, I fear, who deigned to enter the Octagon Room to examine the "interesting collection of books and pamphlets on the present war" and there was no definite indication of excessive enthusiasm over the large war map posted in Commons nor over the new course in the war offered by the department of history. We whistled It's a Long Way to Tipperary only because it was on the contemporary equivalent of the hit parade and when Louis Klipfel, a former instructor, was reported killed in action, we were merely sorry. When for a generation one has heard so much about the hysteria that immediately seized us then, he is puzzled to discover that after some months of war in Europe there is no record of any campus emotion about war other than a chaste and rather senile lack of concern.

It was not until April that the Dartmouth Ambulance was proposed and a committee formed to sponsor this project. We held a mass meeting and we gave a play The White Feather for the ambulance fund. The Lusitania went down May 7; Italy declared war May 23; the Nebraskan sank May 26 and on June 5 four Dartmouth drivers ( R. N. Hall, G. B. McClary, P. D. Smith, L. V. Tefft) with two Dartmouth cars sailed for France. But even such a sequence as this was interrupted by the fact that on May 13 one thousand of us signed a petition of the Polity Club which urged upon President Wilson a stand for neutrality, despite "efforts to embroil the United States in a fruitless and unnecessary war." In short, the Campus was the Campus even then—a useful axiom which with its valuable corollaries might yet, if widely understood, solve most problems of collegiate morale.

So the war did not, as Judge Phillips used to say, "bulk largely in our apperceptive mass." What then were the burning issues of the day? Well, most rife was the imbroglio over compulsory chapel, first raised to the dignity of discussion by the Dartmouth, then used as fodder for essays by the Bema, and finally considered by the faculty with the result that attendance at chapel during examinations was no longer required. Also significant to us then was the proposed merger of Prom and Carnival, a heinous conspiracy of the faculty which was vigorously opposed by the class of 1916 in print, and victoriously opposed, for the Prom program that year included thirty dances (16 one steps, 8 hesitations, and 6 fox trots). For a time we were much concerned over the rumor that Dartmouth was likely to go co-educational, that, in fact, an anonymous donor had already provided funds for three female dormitories. In addition, there was the disturbing canard that basketball and hockey were to be abandoned by the College. These matters —and not the war—seem to have been our problems and our porisms in 1915.

The lot of the baseball team was not a happy one. Although the first trip yielded six straight wins, the team came all the way home to be beaten twice by Syracuse and twice by Cornell. We took Norwich, Yale and Williams, but lost to Brown, Princeton, Rutgers, Fordham, and Wesleyan. Baseball insignia were awarded to the following members of 1916: E. T. Doyle, C. J. Eskeline, L. G. Perkins, E. R. Williams. The success of the tennis team also was limited in 1915, but the rifle team was at its best in wins over Harvard and others with the marksmanship of C. M. Rundlett, E. H. Lawson, and E. S. Winters. In handball the finalists were M. W. Huse and B. Studley. Dartmouth teams chose captains from 1916: in track E. C. Riley, in tennis P. J. Larmon, and in gym. W. B. Garrison with G. B. Fuller as manager.

In the Intercollegiate Glee Club Contest at Carnegie Hall, Dartmouth unanimously won first award, with Harvard and Columbia following. In all activities 1916 cornered the key positions. M. Spelke was chosen manager of varsity debating; R. F. Devoe and A. M. Behnke were president and secretary o£ the Interfraternity Council; the Musical Clubs elected as officers: H. L. Cole, L. W. Joy, and K. M. Henderson; the Arts entrusted responsibility to L. W. Rogers, S. W. Harvey, C. T. Green; the College Club chose as directors J. N. Colby and C. M. Woolworth; the Jack'O decided upon F. S. Wilson, F. T. Bobst, R. F. Chutter, and A. Dean and the Bema selected as mentors E. P. Chase, L. W. Rogers, E. L. McFalls, and A. C. Caiman; in the Outing Club the following were supreme: E. P. Hayden, L. F. Pfinstag, L. H. Bell, O. J. Frederiksen, and A. J. Conley. There were six ex officio members of Palaeopitus from 1916 (J. F. Gile, H. W. Marble, R. F. Evans, R. F. Magill, J. B. McAuliffe, L. R. Jordan) but cast an eye at the roster of candidates for the open places: Behnke, Butler, Colby, Curtin, Davidson, Devoe, Emery, English, Everett, Fuller, Hayden, Holmes, Joy, Larimer, Mack, Mensel, Mott, Parkhurst, Pelletier, Perkins, Pfinstag, Pudrith, Rector, Riley, Rogers, Shaw, Sou tar, Tucker, Williams.

Thus, 1915. The first elevator was installed in the Inn; the Coop, was first organized with J. B. Butler as an executive; the long lost Cuba Falls in the town of Wentworth was rediscovered; now it's lost again. And in view of all this the present college generation has the frenetic temerity to condole with us! College life in our day "must have been monotonous"; Hanover was "so isolated"; we had "nothing to do but study." It strikes me that the best reply to this sort of thing is in terms of the old proverb (If youth only knew, if age only could... .) but with very slight emphasis on the age part.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

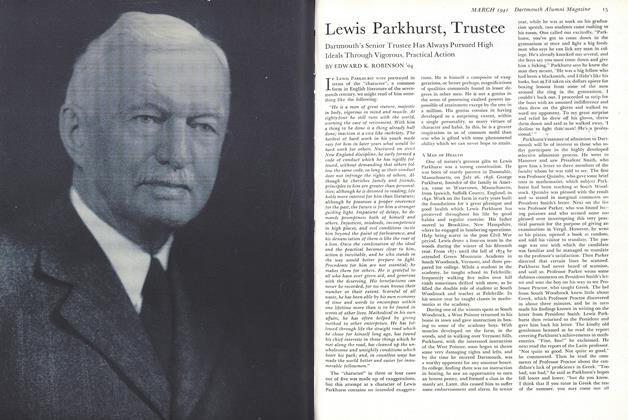

ArticleLewis Parkhurst, Trustee

March 1941 By Edward K.Robinson '04 -

Article

ArticleGreece and Daniel Webster

March 1941 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

March 1941 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1941 By Charles Bolte '41. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

March 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR. -

Article

ArticleA Generation Finding Itself

March 1941