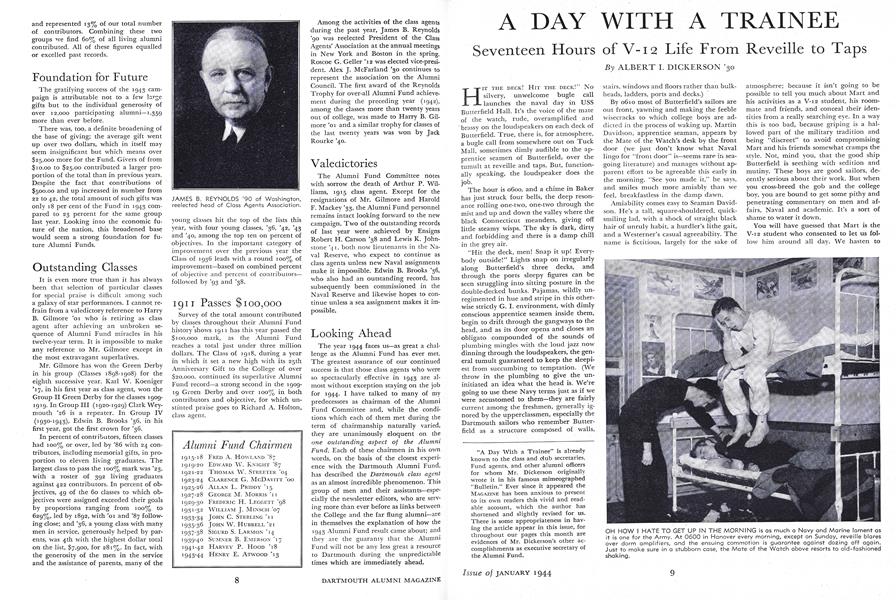

Seventeen Hours of V-12 Life From Reveille to Taps

HIT THE DECK! HIT THE DECK!" NO silvery, unwelcome bugle call launches the naval day in USS Butterfield Hall. It's the voice of the mate of the watch, rude, overamplified and brassy on the loudspeakers on each deck of Butterfield. True, there is, for atmosphere, a bugle call from somewhere out on Tuck Mall, sometimes dimly audible to the apprentice seamen of Butterfield; over the tumult at reveille and taps. But, functionally speaking, the loudspeaker does the job.

The hour is 0600, and a chime in Baker has just struck four bells, the deep resonance rolling one-two, one-two through the mist and up and down the valley where the black Connecticut meanders, giving off little steamy wisps. The sky is dark, dirty and forbidding and there is a damp chill in the grey air.

"Hit the deck, men! Snap it up! Everybody outside!" Lights snap on irregularly along Butterfield's three decks, and through the ports sleepy figures can be seen struggling into sitting posture in the double-decked bunks. Pajamas, wildly unregimented in hue and stripe in this otherwise strictly G. I. environment, with dimly conscious apprentice seamen inside them, begin to drift through the gangways to the head, and as its door opens and closes an obligato compounded of the sounds of plumbing mingles with the loud jazz now dinning through the loudspeakers, the general tumult guaranteed to keep the sleepiest from succumbing to temptation. (We throw in the plumbing to give the uninitiated an idea what the head is. We re going to use these Navy terms just as if we were accustomed to them—they are fairly current among the freshmen, generally ignored by the upperclassmen, especially the Dartmouth sailors who remember Butterfield as a structure composed of walls, stairs, windows and floors rather than bulkheads, ladders, ports and decks.)

By 0610 most of Butterfield's sailors are out front, yawning and making the feeble wisecracks to which college boys are addicted in the process of waking up. Martin Davidson, apprentice seaman, appears by the Mate of the Watch's desk by the front door (we just don't know what Naval lingo for "front door" is—seems rare in seagoing literature) and manages without apparent effort to be agreeable this early in the morning. "See you made it," he says, and smiles much more amiably than we feel, breakfastless in the damp dawn.

Amiability comes easy to Seaman Davidson. He's a tall, square-shouldered, quicksmiling lad, with a shock of straight black hair of unruly habit, a hurdler's lithe gait, and a Westerner's casual agreeability. The name is fictitious, largely for the sake of atmosphere; because it isn't going to be possible to tell you much about Mart and his activities as a V-12 student, his roommate and friends, and conceal their identities from a really searching eye. In a way this is too bad, because griping is a hallowed part of the military tradition and being "discreet" to avoid compromising Mart and his friends somewhat cramps the style. Not, mind you, that the good ship Butterfield is seething with sedition and mutiny. These boys are good sailors, decently serious about their work. But when you cross-breed the gob and the college boy, you are bound to get some pithy and penetrating commentary on men and affairs, Naval and academic. It's a sort of shame to water it down.

You will have guessed that Mart is the V-X2 student who consented to let us follow him around all day. We hasten to point out that he isn't a "typical" V-12 student. For one thing, he's a Dartmouth product (from, incidentally, a Dartmouth family) which puts him in a V-12 minority, although a sizable one. We picked him because we were well acquainted and he wouldn't suspect any sinister motives behind our prying into the private life of a V-12 student. He's far from "average" on several counts. He's in the top five percent scholastically. He's a pre-medical student, one of a relatively small group. His classes are advanced chemistry and zoology courses rather than the big Navy classes in physics, graphics, history and "Naval English." .... But we must get on with the day; it's still 0610, and it's chilly out there on Tuck Mall waiting for the setting-up exercises to start.

Most of Butterfield's seventy-odd sailors are now out front in bell-bottom trousers and skivvy shirts or pajama tops. A short seaman takes his place on a low grass terrace which is conveniently present and gives the commands that line them up and spread them out. The leader is one of the boys—nobody knows how he got picked, but he's a fair and not too violent leader of calisthenics. The whole thing reminds us unpleasantly of dawn in the almost-forgotten past of a Boy Scout camp in the Tennessee mountains—setting-up exercises are grimly the same, the world over. Feeling a shirker's guilt, we obscure ourself by a pine trunk and watch the Russell Sage platoon doing its exercises to our left, the platoons from Hitchcock, Gile, Streeter and Lord across the way—Tuck Mall filled with neatly-spaced jumping-jacks, in bellbottom trousers, white arms flailing the morning mist. Baker is a massive and lifeless pile to our left, the white tower just a dull outline, the weather-vane lost in the grey dampness. From the direction of Tuck School, a platoon comes at a slow double, pours down the bank, and disappears down Tuck Drive. In a few moments it is back, still at a slow double on the upgrade, but its somnambulistic air is gone. . . . . Butterfield finishes its stint, closes ranks, is dismissed, and pours back through the front door (maybe "port" is the word).

It is 0630 by now. We follow Mart to the bare single room we will call Butterfield 266. It contains a double-decker bunk ingeniously contrived by Dartmouth's Department of Buildings and Grounds from two cots; two small drawer-less desks made to Navy specifications by the local contractor, standing side by side against the opposite wall; two straight chairs; and Butterfield's built-in chifferobes. Walls are undecorated. (In some rooms, Mart says, the boys get by with Petty-girl pictures by insisting they are their sisters.) Under the bed, precisely in line, black shoes, sneakers, rubbers and slippers totaling a half-dozen pairs each are in two groups leading from the ends to a gap in the middle..... Mart is moving a dust mop over the floor. It looks clean to us. "What are you doing that for, more exercise?" "You can't take any chances with these chiefs," says Mart. He does a stern imitation of a Chief Petty Officer picking up an imaginary piece of lint from the spotless floor, holding it up to the light, and saying "See!"

Mart folds his two blankets, smooths the bottom sheet, folds the top sheet back at the exact halfway mark of the bed, puts the blankets at the bottom. We ask why. "Regulations," he says. "We have to make 'em over at bedtime. Maybe it airs them, or something," he adds, dubiously.

The roommate, whom we will call Joe Stern, emerges from the head. He has waited his turn and shaved. Mart disappears with razor to fill the possible vacancy, and Joe goes through the bunkmaking, desk-dusting routine. Joe is short, dark, with alert, humorous eyes. He and Mart get along O. K. He's from Boston, where he has had a business course at Northeastern University, and he finds some of his present courses at Tuck School largely reviews of familiar material. He's bright, and his marks are good. He is quietly friendly—seems to have taken our word for the fact we're just a well-meaning amateur journalist, and not a spy.

"Chow down! Chow down! First chow! Snap it up! On the double!" It's the loudspeaker again. Nobody hurries. Mart, shaven and cheerful, picks up his chemistry text and notebook. "Got an Organic exam this morning. Am carrying a couple of fellows in the course, and don't know beans about it myself. Had the watch call me at four o'clock, but couldn't wake up."

Outside they are forming in loose fours on the sidewalk. The mist is rising. Baker chimes six bells—seven o'clock to you. Laggards drift out. "Detail ATTENTION. Right DRESS. Forward HARCH!" And they are off at a brisk pace. More laggards run to catch up with the rear rank, skip into step. We take short cuts, trail along on the sidewalk, out of step. A detail is forming in front of Middle Mass. It is slow getting off, and our detail has to veer to port in unorthodox fashion to avoid collision. We have lost face, so the platoon leader launches maneuvers. "By-files-to- the-rear: first-file-to-rear HARCH! Second- file-etc." This is a complicated maneuver, with files marching in opposite directions, then miraculously reassembling, very handsome to watch. But this morning the boys are not very wide awake, and they get all balled up. The platoon leader, unflurried, patiently reassembles them and starts again. They wheel, they turn, they reverse. It goes better now. A couple of laggards from Middle Mass melt stealthily into our rear rank. You're not supposed to get chow except in formation.

We come to a halt in front of Thayer Hall. A platoon of Marines is already there, facing us, watching the Navy maneuvers with the natural contempt of Marines. A chief appears on the steps. "Well, sailors, the Marines ate first yesterday, you can come first." Two files of sailors leap for the steps on the double. A howl goes up from the Marines. They got there first. "Break it up! Break it up!" (The chief hasn't had breakfast yet, either.) They didn't break it up quickly enough. "All right! All right! Take 'em out and march 'em around for half an hour." Another howl. The Marines come to attention, about face, and march off, as bitter a detail of leathernecks as was ever strafed by Jap.

TWO-MINUTE SERVICE

We slip in behind Mart in the fast-moving file. We pick up compartmented aluminum trays and utensils, select a dry cereal and as we go down the line, tomato juice, muffins, butter, eggs and toast fall into the compartments. We pick up a waiting cup of coffee and follow Mart to a table. (Other sailors and Marines are doing the same things across the way in the Commons.) It takes about two minutes altogether—a darned efficient feeding operation. We noted that Butterfield had rolled up to the port within two minutes of schedule, as posted in the lobby, in spite of countermarching and all "Is this a typical breakfast?" we ask. "It is the breakfast," Mart replies. "Only sometimes the eggs aren't vulcanized," he adds. "Sometimes they drip." They are a cross between scrambled and omelette, we note, reflecting at the same time that they compare favorably with the eggs dished up rather haphazardly to us every morning by a sleepy girl. By our perhaps lax standards, it is a good breakfast, and plentiful We take the trays to a counter, dispose of utensils, paper napkins, cereal boxes, etc. into proper receptacles, brush remaining food into a swill pail, and pile the trays.

We note that it is 0725 as we head for the front door. Mart, who seems in a hurry to get over to the Inn porch for a last-minute review of his Organic, pulls us to the side entrance. "Regulations," he says. Some blue sky is beginning to show through. There is a sign of sun from the direction of Balch Hill, over the roofs of Dartmouth Row. The Inn porch is empty. Too cold. Inside the warm lobby, Mart sinks into a divan and dives into his notebook. Peggy Sayre and little Fordy appear on the steps, a little sleepily. We explain that we're with the V-12 for a little study before class. "Yes," she says, "and to leave papers on the floor and ashes on the rug." Four Marines on the other side of the lobby, just sitting, seem to think this is a reasonable expectation.

Broad bars of golden sunlight pour between the buildings of Dartmouth Row and slant across the campus. Who would have guessed two hours ago that it would turn into such a noble day? It's almost 0800 as we cross the campus toward the Organic exam in Dartmouth Hall. Standing around in the corridor are sailors and civilians in about equal numbers and a few Marines. There is an execution-chamber air to the scene. "Doc Bolser's a demon on the true-false. Knows all the tricks and will catch you every time." When the hour strikes, the door opens. Exam papers are distributed around the hall in such manner as to make cribbing inconvenient. The men slip into the chairs and go to work. Professor Bolser and an assistant walk quietly about the room, occasionally responding to the summons of a raised hand. One or two finish and leave half-way through the period. Mart stays almost to the end. Outside there is a retrospective knot of students. "A little hairy in spots," someones says. "I'm afraid," Mart says to a companion, "that we didn't do so well." The companion looks up, betrayed and incredulous. "I saw the master sheet after the exam, and most of my answers there on the second page seem to have been wrong," Mart explains. "Gus had the same answers you did," the companion says, as hope mingles with the doubt and alarm on his face. This thought seems to reassure him. ....

As we walk to the gym, the morning is in full glow. There's time for a smoke on the steps. Mart heads for the locker room and we stroll through the Trophy Room. A juke box is going. A Marine drill sergeant in cap, uniform, and sneakers is teaching the polka to someone in a nondescript maroon sweatsuit. Their hands are linked, like a romantic couple iceskating, and they swoop about the floor. The Marine is good In the steamy pool, bare swimmers, or prospective swimmers, splash and kick. One of the chief specialists is in charge—most of them are former athletic coaches. A new arrival sticks a tentative toe in the water. "It's cold," he says, incredibly. The whole place steams like a stew pot The juke box is now playing boogie-woogie. The Marine sergeant is doing a solo. He obviously cuts quite a figure in the ball-room. . . . . By 0915 about a hundred men are out on the dirt floor of the west wing of the gym, engaged in desultory horse-play, waiting for the instructor in Combative Activities—commando tricks, etc. One day they box, another day they wrestle, today they have Combative Activities.

The instructor in Combative Activities and his assistant appear. They are, respectively, the dancing Marine and his polka partner.

Combative Activities start with violent calisthenics. The dancing Marine has the boys flinging themselves wildly in all directions, biting the dust every few seconds. Then come the commando tricks. The Marine calls a man out of the ranks to demonstrate on—the victim is a replica of Firpo on a four-fifths scale. The victim is induced to undertake a certain offensive maneuver, and winds up flying through the air, or with his neck under the knee of the Marine. "You get his arm over your shoulder like this," the Marine demonstrates, "and then you break it." Firpo looks apprehensive In the East wing, another group of a hundred is getting boxing instructions. The gloves haven't come yet, and, in pairs, they are doing jabs, hooks, and parries in unison. The juke box is silent To get the boys to class before the 1010 late bell, these activities have to end by 0950, and they do. Commando feats, mingled with rough horse-play, end. Mart claims that he always picks out the smallest sailor he can find for his partner in these contests, but today, anyway, he's got a rugged opponent. At the moment he is jumping around in pain, his black hair bouncing up and down. He has just had his shins kicked. Now he grins in anticipation. It's his turn. But the period is over.

We go out in the sun and read the headlines about the war in Italy on the gym steps. As four bells strike for the 1000 classes, Mart appears from a quick turn under the crowded showers, wet-headed, dishevelled and cheerful. He seems to know about half of the passersby. The quick trip across the campus is about as close to hurrying as we come all day, because we've got to be at the Natural Science Building by 1010. When we get to Silsby's steps, there is still time for Mart to beg a drag on a sailor's cigarette. The class is Zoology 61, General Physiology, under Assistant Professor Roy Forster, a well- spoken-ofteacher in his middle thirties. Thirty or forty sailors and civilians, including a few Marines, fill the small classroom. A sailor "section leader" calls "ATTENTION." The sailors and Marines snap to their feet. The civilians drag it up more slowly. We are shamefacedly last. "SEATS." The section leader silently checks the attendance The lecture is on catalysis and digestive enzymes. There is a neat, detailed outline of the lecture on the board. The pace is fast, briefly interrupted here and there by a student's question, or the instructor addressing a question to a student about the relation of the material to something that has gone before. When we hear six beils, Mr. Forster is finishing the last sub-head of the last point of his lecture outline.

It's a short haul to the Steele Chemistry Building for Comp Lit 13, and there's time for a cigarette on the steps. The course is Types of American Thought. Herb West calls "ATTENTION," and "SEATS," and then asks the men to spread out into alternate chairs. There's a quiz We chatted with Herb West while his sixty sailors, Marines and civilians scribbled inside about R. Waldo Emerson. Only a few of these, it seemed, were doing unsatisfactory work, including some Marines who decided that they were more anxious to get into combat than study Comp Lit and had concluded that flunking out was the quickest way to accomplish this. (We have reason to believe that this is a very poor notion.) .... Some twenty minutes are left after the quiz, for further lecturing on mysticism, the Over-Soul, and the mooted medico-literary question whether Mrs. Carlyle died a virgin, "which," Professor W. avers, "would explain a lot."

When eight bells strike for high noon, a khaki-clad squad marches briskly along the hillside highway in front of Wilder Hall toward their barracks in North Fayer. This is eight-fifteenths of Dartmouth's army—a battalion of fifteen medics. Their colonel was recently detached, and they are now under the command of the C. O. up at Norwich University, with Dr. Syvertsen and a sergeant locally in charge. General Syvertsen is also admiral of the Medical School Navy, a task force of 33 midshipmen, some units of which are cruising jauntily down this same highway to the USS North Fayer. The fleet, decidedly at ease, is a peril to the army's navigation. .... These midshipmen, in their new blue suits and white caps, all resemble admirals. They don't rate salutes from seamen, but one of them dressed up in his new blues, cap, and overcoat and took a turn down Main Street, with relaxed and sober grace returning a hundred or so shoulder-dislocating salutes. On his return to Observatory Hill, he pronounced the uniform satisfactory.

Mart's long-legged pace toward lunch is unhurried but ground-covering, past russet-ivied Wheeler, the warm red brick of the library, the paler walls of Webster. It is too late for Butterfield's first chow formation, and we march direct to Thayer Hall and proceed with purposeful dignity into the verboten side entrance, against the exit traffic, and into the chow line. ("All you've got to do is act like you were going somewhere.") It looks as if it hasn't worked when a belligerent-faced Chief accosts Mart. It is the same Chief who sent the howling Marines off for a pre-breakfast hike when they failed to break-it-up way back there before breakfast and the rising mist had brightened the day. But what he is asking Mart is, "Who is this guy with you?" He somewhat dubiously accepts our explanation.

The way food falls on our tray from all directions as we slide it down the service bar in front of a battery of white uniforms recalls our childhood pictures of manna pelting down on the Israelites, whom we clearly envisioned, bowed but unprotesting under the downpour of cookies and bananas. Our swift and bewildered progress is briefly interrupted as one of the gals in one of the uniforms inquires if we have permission to eat there. The next time we look at our tray, it has a bowl of potato soup, a couple of rolls, a large helping of macaroni au gratin, chef's salad, raisin pudding, and two bottles of milt on it There isn't much more conversation at lunch than there was at breakfast, as we have a Zoo lab to make at 1230. But even so, Mart seems to hurry neither himself nor us, and as the day wears on, we begin to wonder a little how Mart gets to so many places to do so many things without ever seeming to hurry.

LIFE IN A LAB

Back to the same basement room in Silsby where we heard the enzyme lecture in the morning. Roy Forster's lab schedule (which begins at 0730) is posted on the board. This lab is from 1230 to 1530. The idea is to open up a frog's heart, treat it with something, bring it back to normal again with some synthetic frog's blood, excite it with another juice, subdue it once more, sock it again, etc., getting a magnified picture meanwhile of all these vicissitudes of a tortured heart by means of a lever delicately hooked up to it which makes, on a revolving smoked drum, marks resembling a graph of the stock market from 1920 to 1940. That's quite a sentence but you will perhaps get the idea. Professor F. is opening a clam for purposes of demonstration. But the animal room got too hot the other day, and this clam, and the next one, and the next one, while not exactly dead, are just too tired to respond to any stimulus. Clam after clam proves lethargic, until what might have been a magnificent platter of clams on the halfshell has gone into the garbage can. Wasteful, profligate Science, we sigh.

Meanwhile Mart, eight or nine other pre-medical sailors, a couple of civilians, and one Marine proceed to anesthetize their frogs. They work in pairs and trios. Another sailor and the Marine work with Mart, and their frog, Joe, turns out to be one whose brain was removed last week, with no apparent effect beyond a slight dent in the head. When Dick, the sailor, applies the scalpel, Brainless Joe kicks like hell and has to be put back in the ether jar. Mart and Dick are an efficient pair, and they got Joe's heart hooked up and the marker starts ticking like nobody's business. Mac, the fat Marine, confidently contributes an unbroken stream of conversation which he obviously feels is shot through with wit, while Mart applies enzymes with eye-droppers. "A typical Marine," a neutral observer explains under his breath. "Have you heard the one Mac offers. A groan spreads through the laboratory, and Mac stops and pretends injured feelings. "Oh go on, Guadalcanal, and tell it if you want to," Mart says indulgently, dropping some synthetic frog's blood on the agitated heart. Mac noisily gives his story, which isn't too bad He didn't want to come to Dartmouth. He was at Springfield YMCA College, studying to be a physiotherapist. Claims he didn't even enrol in V-12—just got orders to come to Dartmouth. He isn't glad he's here. He can learn some anatomy and physiology, but Dartmouth offers no physiotherapy. The system sort of miscarried on Mac Benger, a sailor, says he has just heard that the Navy is going to send certain classes of pre-medics to other duty instead of Medical School, as promised. Work stops while the sailors listen to Benger's story. It's a complicated situation—seems the medical school classes are going to be full. Some of the boys, like Mart, had provisional medical commissions, and, on advice of superior Naval authority, had resigned them for V-12 status. Nobody, high or low, seems to know just what is going to happen. The sailors go back thoughtfully to their frog hearts. Most of these kids have been planning for years to be doctors.

A SILSBY ODYSSEY

All the boys are busy, and Roy Forster is still opening clams. To shield ourself from this rapine of the beautiful bivalves, we wander out into Silsby's corridors. Gunfire attracts us to a basement room at the other end of the building. There, in what apparently used to be a sort of janitor's junk room, A 1 Foley of the History Department is conducting a physics lab for a dozen Marines. A machine in the corner is pumping gas for the building's Bunsen burners. Professor Foley takes a sort of pride in, as it were, personally supplying gas to all of Silsby Hall. A half dozen .22 rifles are rigged to shoot into pendulum targets. By multiplying, dividing, or adding, the weight of the bullet, the distance that the impact pushes the target, and the target's weight, you get the muzzle velocity of the bullet. A 1 offers us a shot, but since you couldn't possibly miss, this is no challenge to our sporting instinct and deadly aim. The Marines are doing a lot of plain and fancy weighing and computing. .... In the big lecture room on the main floor, Fergy Murch, director of physics instruction for V-12, the toughest expansion problem of the wartime curriculum, is picking up after a lecture and preparing for another, in an atmosphere dominated by decor of dinosaur fossils.

On the second floor, Professor Meservey of Physics and Professor Waterman of History are presiding over a sunny room which formerly was a botany lab, where sailors and Marines are running little cars up and down tilted panes of glass. It has something to do with the efficiency of the inclined plane. In another place, objects are being weighed in and out of various colored liquids. This has something to do with specific gravity In the thirdfloor room just above this one, Professor Lathrop (Art) is pretty busy helping more bluejackets through a morass of mathematical formulae. Some have been measuring the thickness of a piece of steel by three different and fantastically complicated devices. (We could see at a glance that it was a quarter-inch thick.) Others are whacking away at an elongated coiled doorspring suspended from the ceiling and holding up a weight. It makes undulating vibrations and this, we are told, has something to do with the simple harmonic scale.

In a neighboring room Professor McNair (Geology) is surrounded by aerial photographs, maps, and Marines. This is the course in map-reading. Nobody has any time for us, so we wander down the hall to more aerial photographs, maps, and Marines, under the tutelage of Professor Morrison (Art) and Professor Guthrie (Romance Languages). A bell rings and the class ends. A Marine comes up afterward to ask if there is an advanced mapreading course to take after this one. "Not until you get to Quantico." The Marine Corps is strong on map-reading. Hugh Morrison shows us how you mark the area of a photograph on a map and explains how, if you know the distance between the lens and the film in the camera, and the height of the plane, you can figure the scale.

Back in the basement, Brainless Joe's heart has run the gamut of enzymatic emotion for Mart and Dick, under Mac's conversational observation, and has drawn a beautiful chart. Professor Forster, barely visible behind a heap of discarded mussels, has finally found an ambitious clam which is performing beautifully. The indefatigable Joe has been bequeathed to another team whose set-up was less skillful or whose frog had less oomph. Most of the others are through with the experiment and are beginning to write it up. "This is a fast class," says Forster. "It took the last class all three hours, and even then some of them weren't through." Conversation rises or falls without interfering with work, while Professor F. and your correspondent sit and smoke. Mac dispenses the scuttlebutt of the Marine Detachment.

Ambrose, the Ambitious Clam, and Jolting Joe, of the missing mentality but the magnificent heart, are still going through the motions when Mart departs. It is our first return to Butterfield since 0650. It is almost 1530, afternoon liberty time. Mart has a fiancde in town and we decide to give him a break. A duenna for Competitive Activities, Zoo lab and Comp Lit is one thing, but during liberty a duenna is another matter. As Mart signs out "Town" on the liberty book on the Mate of the Watch's desk, we decide to find out what other trainees do during afternoon liberty. Allen's soda counter is full, and strollers cover Main Street. The second and third floors of Robinson Hall are teeming with activity. Pingpong balls give out a racket as of small-calibre machine guns from the Little Theatre, where the chairs have all been taken out and a battery of tennis tables installed. There's even a half-table rigged against a wall where a solitary fellow can play against himself. In the Arts Room, Marines are playing pool. Cribbage, chess, poker, other card games are being played in the small rooms which used to serve various publications and activities. A pile of cases of empty coke bottles besides the coke machine testifies to the consumption since morning. From the quarters formerly occupied by Germania on the top floor, jazz pours. Jive-loving, foot-beating gobs cluster about the victrola, while the more passive type read popular magazines on divans. Down the corridor, we open a sound-proof door and step into a different world, the door closing behind us. Deeply carpeted, luxuriously furnished, this former headquarters of the French Club now houses the Carnegie-bestowed Capehart machine and musical library. Brahms is being played a small group at the Capehart. Across the room, a solitary little sailor is pretending to read The New Yorker.

We have a date with Mart at 1750 at Butterfield. We have a feeling that otherwise, around chow time, he would stroll by one of the dining halls as a chow formation marched up, and dive into the rear rank. Since we caught on to this, we've found it a frequent performance. Two sailors will be sauntering down a sidewalk. A chow formation marches down the street. The sailors vanish. You blink, and there they are, marching briskly, in step, in the formation. Neat; time-saving Mart, sitting on the straight chair in But- terfield 266, is thoughtful. "I'm just trying to figure out the angles." .... "What angles?" .... "The angles about the medical school situation. I spend most of my time in the Navy trying to figure out the angles." .... "But you're all set for NYU in January, aren't you?" .... "I think so. You never know." .... We get a picture of 2000 boys, out of colleges and high schools, enmeshed in the massive operations of the United States Navy, entangled in a multitude of strange regulations, being carried along in a vast new educational experiment which has to be worked out more or less as it goes along— -2000 boys of the country's largest V-12 unit, sitting in straight chairs in Dartmouth dormitories, figuring out the angles. .... "You ought to get in about the double adjustment these high school kids have to make," Mart says. "What double adjustment?" .... "Well take these high school kids. The Navy regulates everything they do. It tells them when to get up, when to eat, when to go to bed, what uniform to wear today, how to brush their teeth. Everything is regulated. But with their class work it is just the other way. In high school they've sort of been led by the hand. They get in a college classroom and find they are on their own. Some of them are having a hell of a time getting adjusted to it."

"Chow down! Chow down! First chow! On the double!" It's the brassy loudspeaker again, but a slightly more dulcet voice. The sailors drift toward the ladder with the same absence of haste. The low sun over Tuck's pines fills the Vermont sky with a golden radiance and envelops the curved dark green masses of Tuck Mall's elms with a soft gold mist. Under Butterfield's pine, it is the assistant platoon leader this time who is assembling the formation on the side-walk. "Snap it up, mates, snap it up." Madden, like all the platoon leaders, is one of the 150 V-ig trainees from the fleet who were designedly dispersed through the dormitories, just as the 400 trainees from Dartmouth were. The assistant leader's toga had not fallen lightly on his shoulders. His face wears the vaguely belligerent mask of one who once worked hard at the role of tough and worldly sailor. "This," says Mart, moving toward the formation, "sometimes gets a little tough to take." There is laughter and chatter in the group. "Knock it off, mates, knock it off Dress it up." They "dress right," spacing themselves an arm's length. "Square your hats." (This means make them round, and jam them down on your forehead where they bother you. The boys like to wear them lightly on the back of the head.) Some of the boys, with a mechanical and impersonal obedience, round out the more rakish angles they've creased in their hats, and shove them down over their eyebrows. Madden doesn't seem to bother them much—just something you have to take, like getting up in the morning, an irritation only when you're in the wrong mood. "Right FACE Forward HARCH. HUP-two-three-four. HUP-two-three-four. HUP HUP.

While the Butterfield platoon stands at ease in front of Thayer Hall, we talk to the chief on the steps. He's a taciturn Texan—a high school principal from Beaumont. "Oh yes," we say, trying to think of something about Beaumont, "there's a major league farm club there, isn't there?" "Yep, the Tigers" (if that's it—we forget) he confirms. "Also, Harry James came from Beaumont." These chief specialists, mostly former coaches, have been especially indoctrinated for the V-12 program. They have charge of the dorms and help with the physical training program. They, and the yeomen, pharmacists mates, etc., form the Ship's Company. . . . . We have distracted the chief, and there is a gap in the chow line. He gives the high sign, and Butterfield jumps for the steps in two fast-moving files. Again we fall in behind Mart

Tonight it's scallops, and darned good, topped off by ice cream-sherbert squares. Don Mayberry sits down with us. He's Butterfield's platoon leader, a well-built, confident, goodlooking fellow—good features, curly hair, the sort of face you used to see on the cover of The Americati Boy, but maturer. Went to St. Paul's, been in the Navy since 1940, came to V-12 from a destroyer escort in the Caribbean, where he was bosun's mate, second class. "Was it hard getting into V-12 from the fleet?" . . . . "No. I didn't think I wanted to be in. My commanding officer called me in and asked me if I wanted to try for it. He knew I wanted ultimately to be an officer. My father looked into it, and I decided to make a try for it. It wasn't hard." We ate fast, because our watches showed that the Nugget's 1815 show had already started. "Have you found out anything interesting today?" Don is now drawing us out. We parry. (As the reader has seen, the day's revelations wouldn't even agitate the responsive heart of the late Brainless Joe.)

"I told Don you were making a special investigation for the Secretary of the Navy," Mart explains on the way out. "He was pretty upset about the way the formation got balled up on the way to breakfast." We recall the unflurried way Don had straightened out the confusion, put the detail through its paces. "I should think he would be a good platoon leader," we offer. "He is," says Mart. "He's responsible for seeing that we do all the things we're supposed to do. Dirty job, but he does it well. He has to give us hell sometimes times, but the way he does it, the boys don't mind. Maybe it's because he does all the things himself. Just a natural officer, I guess." .... It is really a stinking movie. Joan Crawford and Fred Mac Murray in one of those spy thrillers of the "underground." As we get out, just before 2000, the moon is coming up. We offer to leave so Mart can study his physics, but he insists he doesn't need to.

It would be easy to continue with the talk of the next few hours: Mart lounging on his lower bunk; sundry visitors drifting in; Joe Stern, the roommate, coming in later, climbing with Life into his upper bunk, listening with twinkling eye when Ike from next door (who, like Joe, came from Boston and Northeastern University and who seems to regard us as a visiting big shot) tells us in the most earnest manner how easily he does his work and how admiringly his professors regard him. We ask for a pipeful, and as Ike dives next door for his Granger, somebody mutters it's the first time anybody ever got anything from Ike People go up and down the corridor, past the open (by regulation) door. Nobody seems to be studying. Mike, a sharp-faced, brighteyed little freshman bluejacket from the Fitchburg High School, comes in with a paragraph for English (they do paragraphs, these days, instead of themes) for Mart to criticize. There's the other youth who deeply feels the injustice of the unbroken series of E's he has received from Professor McCallum.

"What did you get," asks Mart, "on that one I wrote for you last week?" (Mart keeps himself in cigarettes writing paragraphs for freshmen.) "C-plus," says the freshman. Mart is insulted and incensed At 2250 there is a warning, and at 2300 the loudspeaker's brassy blast gives: "Lights out! Knock it off! Lights out!" We say goodnight. The campus grows quiet, softly silver under the radiant moon.

OH HOW I HATE TO GET UP IN THE MORNING is as much a Navy and Marine lament as it is one for the Army. At 0600 in Hanover every morning, except on Sunday, reveille blares over dorm amplifiers, and the ensuing commotion is guarantee against dozing off again. Just to make sure in a stubborn case, the Mate of the Watch above resorts to old-fashioned shaking.

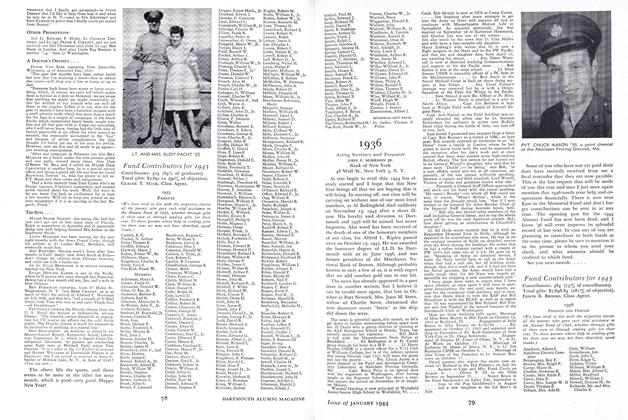

VERSATILE FUND EXECUTIVE. Albert I. Dickerson '30, who as executive secretary is key man in Alumni Fund successes year after year, and who in addition can turn out such articles as this about a day with a trainee.

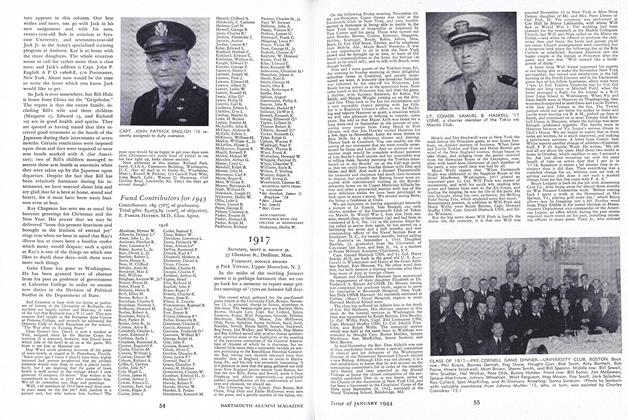

STANDING IN LINE is one inescapable part of being a V-12 trainee and gradually becomes second nature. These sailors are waiting their turn for noon chow at Thayer Hall.

INSIDE THAYER HALL the trainee becomes a part of this bustling scene. Two lines speed up cafeteria service for sailors and marines, who pronounce both organization and food good. A second mess hall for the V-12 Unit is operated in the former Freshman Commons.

STANDING WATCH, a dormitory duty assigned in turn to all hands, gives the "Mate" control of the loudspeaker system, whose clarion call sounds worst at dawn, best at chow.

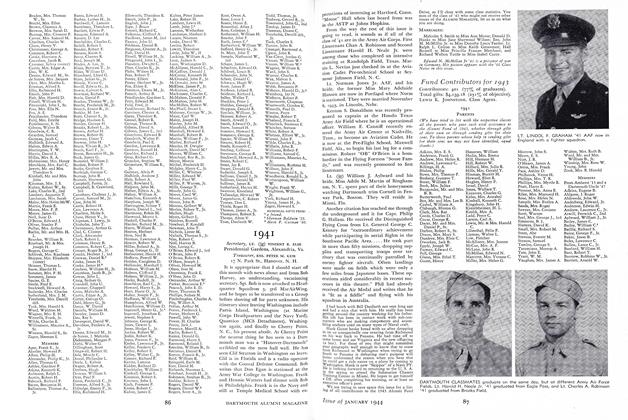

LABORATORY SESSIONS bulk large in the academic work of V-12 trainees. In the above scene, Dr. Roy P. Forster, Zoology professor whose clam-opening abilities are celebrated in this article, demonstrates apparatus for measuring the velocity of a nerve impulse. Mixture of civilians and trainees in this pre-med course is typical of today's classes.

IMMEMORIAL CUSTOM OF BULL SESSIONS in student rooms shows no signs of abating under V-12. Arrival of the weekly Dartmouth Log, above, seems to have caused a temporary halt in the discussion of all things under the sun, but particularly the war and women.

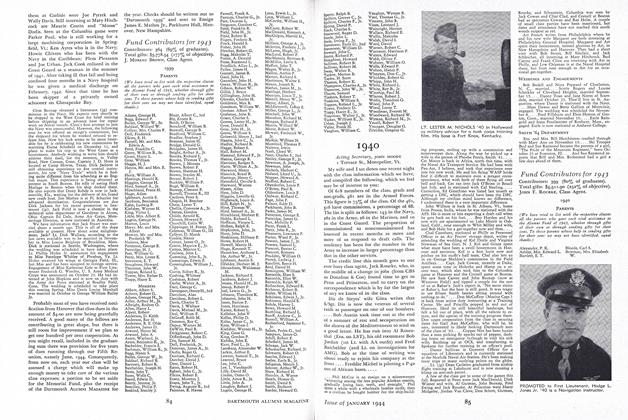

Lt. (jg) LEWIS K. JOHNSTONE '41 produced one of leading class records after taking over as Fund Agent on short notice.

"A Day With a Trainee" is already known to the class and dub secretaries, Fund agents, and other alumni officers for whom Mr. Dickerson originally wrote it in his famous mimeographed "Bulletin." Ever since it appeared the MAGAZINE has been anxious to present to its own readers this vivid and readable account, which the author has shortened and slightly revised for us. There is some appropriateness in having the article appear in this issue, for throughout our pages this month are evidences of Mr. Dickerson's other accomplishments as executive secretary of the Alumni Fund.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

January 1944 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

January 1944 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

January 1944 By JOHN MOODY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

January 1944 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FRANCIS T. FENN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

January 1944 By JOHN E. MORRISON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

January 1944 By LT. (jg) VINCENT R. ELSE, ENS. PETER M. KEIR

ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30

-

Article

ArticleHanover Holiday Plus Alumni College

May 1937 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Books

BooksAN ACCOUNT OF CALLIGRAPHY PRINTING IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

March 1940 By Albert I. Dickerson '30 -

Books

BooksNEVER SAY DIET.

November 1954 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Books

BooksAn Authoritative Obituary for "Well-Roundedness"

June 1962 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Article

ArticleValedictories to Retiring Class Agents

April 1942 By Harvey P. Hood II '18, Albert I. Dickerson '30 -

Cover Story

Cover Story24th Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1939 By Luther S. Oakes '99, Edward K. Robinson '04, Fletcher R. Andrews '16, 2 more ...

Article

-

Article

ArticleA GRADUATE MANAGER OF NON-ATHLETIC ORGANIZATIONS

January, 1912 -

Article

ArticleMRS. HERBERT D. FOSTER DIES SUDDENLY IN HANOVER

August, 1926 -

Article

ArticleW. J. T.

NOVEMBER, 1926 -

Article

ArticleDrama Editor

November 1955 -

Article

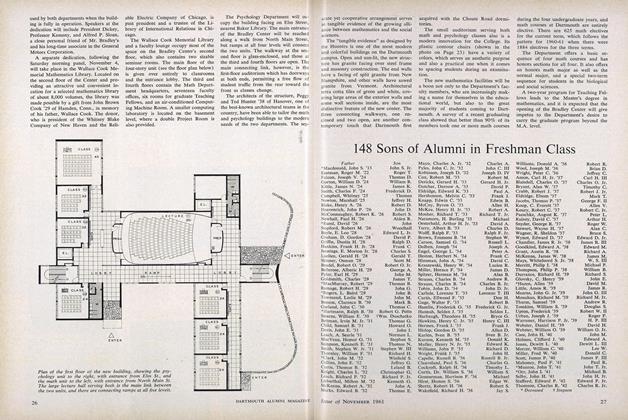

Article148 Sons of Alumni in Freshman Class

November 1961 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

July/Aug 2009