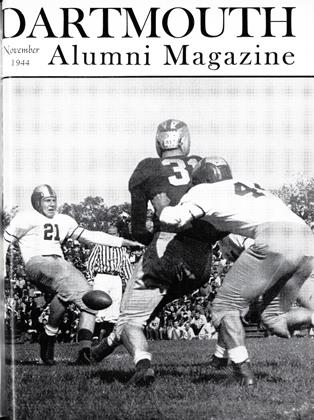

Inexperienced, Injury-Riddled Eleven Still Seeks First Win After Three Starts; Notre Dame Power Jars Indians, 64-0

IT IS THE UNHAPPY LOT of this reporter to begin his incumbency in this department by describing the worst debacle in the history of modern Dartmouth football. I say modern advisedly, for a hurried glance at the records, on this the day after the disaster, discloses that Dartmouth has been even more soundly trounced by Harvard and Yale back in the earlier days of Big Green football. One of Gil Dobie's Big Red teams, if memory serves, also administered a very thorough pasting in the early twenties before the Hawley renaissance. But even that defeat, avenged so thoroughly in subsequent years by Eddie Dooley, Jim Oberlander, and company, was not in the same awe-inspiring category as this fiasco in the. Fenway. To point out that Dartmouth was beaten by the currently strongest team in the country (with the possible exception of the Chicago Bears and the Green Bay Packers) is cold comfort. It is no fun to be beaten by anybody that badly.

The capacity crowd of 40,000 in Boston's Fenway Park on October 14 probably came for three reasons—first, there were many thousand loyal followers of the Green who came to see their boys play football, win, lose, or draw; second, there were many thousands of loyal Hibernians from Greater Boston who wanted to see the Fighting Irish (Dancewicz, Gasparella, Maggioli, and Kelley) in action, a pleasure which has been denied them, for some unaccountable reason, up to this time; third, there were many other thousands of subway alumni of Notre Dame and sundry sports lovers who merely wanted to see a superlative football team in action. All three groups, it is pleasant to record, were happy, although the degree of happiness was roughly in ascending order. Dartmouth's cheering, it might be parenthetically added, was largely contributed by the local alumni and by the drill teams of Marines and Navy trainees who performed between the halves. The rest of the trainees were wisely confined to their quarters in order to study for final examinations which were scheduled to start the Monday following the game. So the trainees, who would have given anything to make the peerade, spent the afternoon listening glumly to the radio and watching the autumnal rains wash the last leaves from the trees.

The game itself was strictly no contest. The boys from the Hanover hills were outblocked, outtackled, outrun, outweighed, and outscored. In fact, they submitted to every sort of indignity except being outfought. On the contrary, they rattled a good many Notre Dame teeth with their hard tackles, particularly in the first quarter when their defensive work was very good indeed. They kept on trying right on down to the closing whistle, despite the ever-widening margin of defeat staring them in the face. They even surged up the field a couple of times in the closing moments of the game, following a brief flurry of pass completions, just as though the entire season depended upon a Dartmouth score at that particular time. In his tribute to the team in the Boston Herald, Arthur Sampson pointed out, "The inexperienced Dartmouth youngsters put up a spirited fight. They fought their hearts out against overwhelming odds. They simply had neither speed nor the power to cope with the wearers of the Kelly Green shirts." That says it clearly and succinctly. The Dartmouth boys were in there swinging all the way. But they just weren't good enough.

An appropriate sample of the afternoon can be gleaned from the opening play of the game. Following Dartmouth's kickoff, Bob Kelley, Notre Dame's great halfback, dashed around Dartmouth's right end for 52 yards to the lg-yard line. Only a great stop by Britt Lewis, Dartmouth safety man, held off a touchdown before the game was a minute old. Notre Dame was held on this sequence of downs by some great defensive work on the part of the Big Green line, with Dartmouth taking over on her own five-yard line. The rest of the first quarter saw only a single Notre Dame score and it looked for a while as though Dartmouth were going to win a moral victory by sheer fighting heart. Even visions of another fifth down upset began to dance before the misty eyes of old Dartmouths at this point. And then came the deluge. Twenty-four points were scored by Notre Dame in the second period alone, and Dartmouth left the field at half time trailing 30-0. In the third period, Notre Dame was held to a single tally, only to have the dam break again in the final quarter when the Irish scored 27 points. This brought the grand total up to a depressing 64-0.

It was one of those days when almost everything the Indians did went wrong and almost everything Notre Dame did paid off. This is, of course, merely another way of saying that they were good and we weren't. Coach McKeever of Notre Dame had an apparently endless supply of backs, all of whom went tearing by, as well as a large and talented assortment of operatives in the line. So well distributed was the Notre Dame power that their scoring was done by nine different backs, with only one of them scoring twice. The second and third team line throttled the efforts of the Green from the T formation with the same murderous gusto that their colleagues on the first team had exhibited.

For Dartmouth, the guards and tackles did yeoman service at times, stopping the bewildering succession of spinners, cross bucks, and quick-opening plays that the Irish produced from behind a stonewall line. Marine Dick Bennett of the Indians, who won his letter in a bigger game during eighteen months in the South Pacific, played his heart out at left halfback before a hometown audience. Little Herb Fritts at right half threw his 160 pounds into the gargantuan Notre Dame line again and again, as did chunky Harry Bonk, who substituted for the injured Hal Clayton at full- back. Halfback Tom Kavazanjian caught a couple of Britt Lewis' passes and brought the Green into one of its three scoring positions. But the glory to Dartmouth was of the anonymous variety, given by boys who stuck to their guns until the last shot was fired, who refused to lie down in the mud of Fenway Park and admit they were licked, and who kept trying all the way.

Striking along the ground and through the air, Notre Dame rolled up 19 first downs to 6 for Dartmouth; at least two or three of the latter were donated to the Green by Notre Dame penalties. The figures for total yards gained by rushing are even more terrifying. Notre Dame gained a tremendous total of 429 yards by this means, while Dartmouth gained a total of minus 18 yards. Read that again. Minus 18. For our total afternoon's work on the ground, we ended up with a net deficit. The huge Notre Dame forwards broke through time and again to throw our backs for a loss before they could get started. On one of the brief occasions when Dartmouth was within shouting distance of pay dirt, they started out with a first and ten on the Notre Dame 15-yard line, only to end up with fourth down and something like 30 to go back on the 35-yard line. Only in the passing department did Dartmouth rival the Irish; the Indians took to the air on 17 occasions and completed 5 of their tosses for a total of 111 yards. The Notre Dame record was 8 out of 13 for a total of 125 yards. These aerial adventures, by the way, brought the Notre Dame yardage to the astounding total of 554 for the afternoon.

All in all it was, in the words of the English poet describing the Battle of Blenheim, a famous victory. But not for Dartmouth.

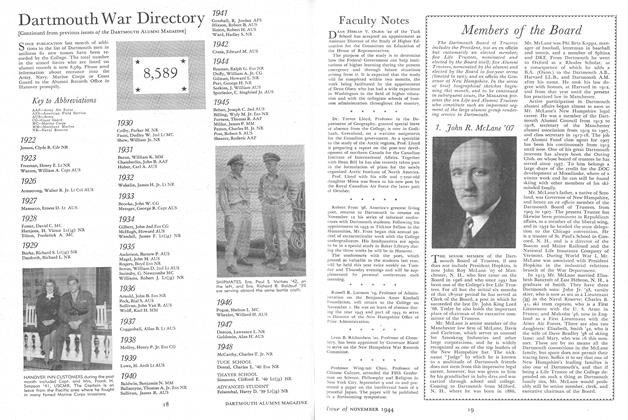

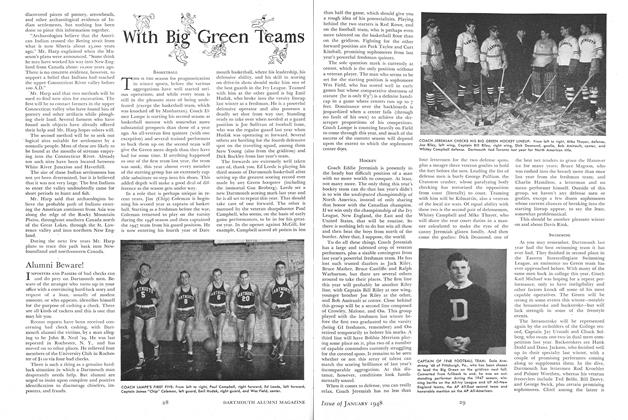

PROTECTION PLUS enabled Notre Dame to make its passes click against Dartmouth. On this second-period play, Boley Dancewicz (arrow) is literally surrounded by teammates as he goes back to toss a 23-yard forward to Steve Nemeth, shown at top right of photo.

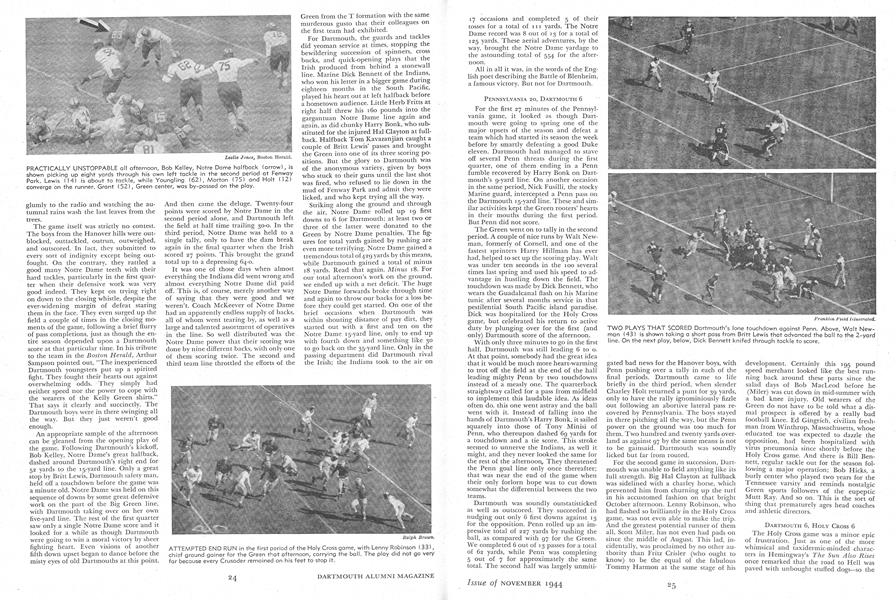

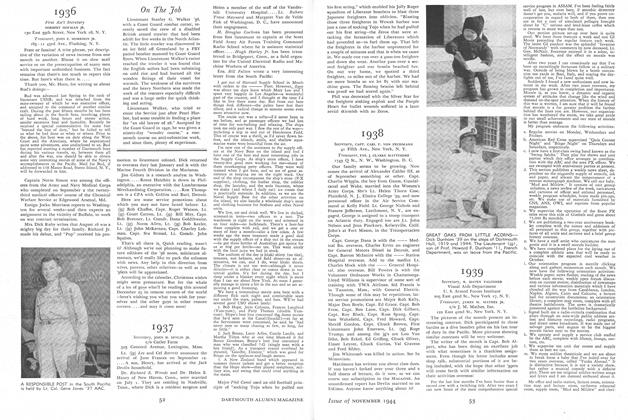

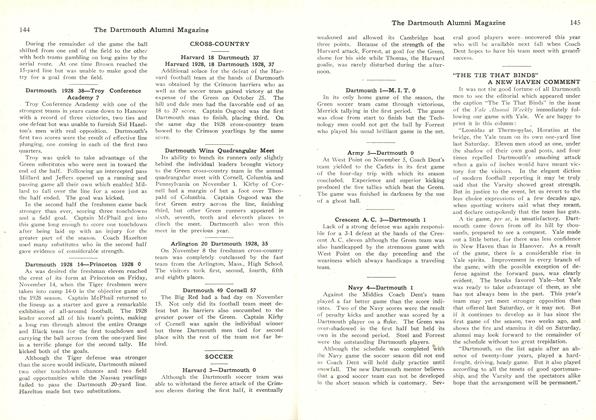

PRACTICALLY UNSTOPPABLE all afternoon, Bob Kelley, Notre Dame halfback (arrow), is shown picking up eight yards through his own left tackle in the second period at Fenway Park. Lewis (14) is about to tackle, while Youngling (62), Morton (75) and Holt (12) converge on the runner. Grant (52), Green center, was by-passed on the play.

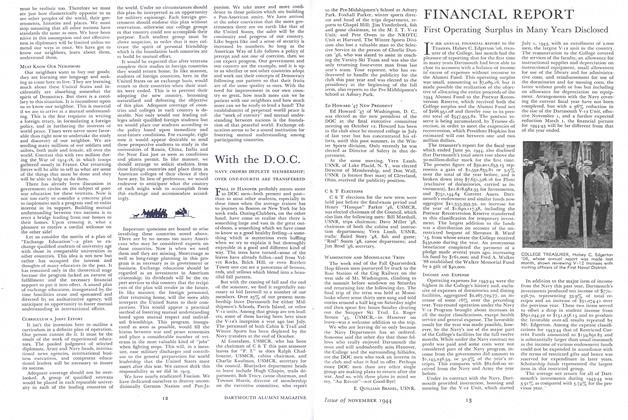

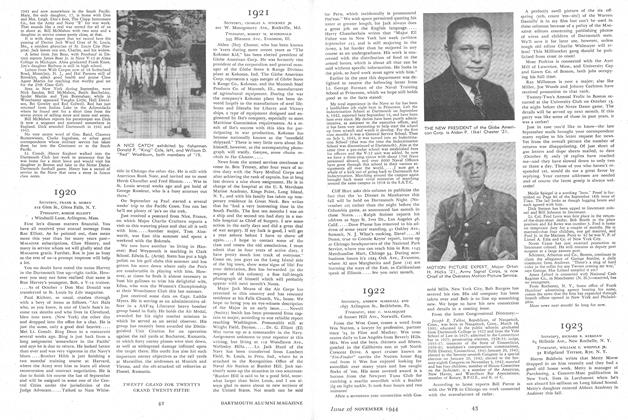

ATTEMPTED END RUN in the first period of the Holy Cross game, with Lenny Robinson (33), chief ground gainer for the Green that afternoon, carrying the ball. The play did not go very far because every Crusader remained on his feet to stop it.

The Magazine editors take very greatpleasure in introducing this month asSports Editor and staff colleague, Prof.Francis E. "Red" Merrill '26, whose writing skill and comprehensive knowledge ofthe Dartmouth athletic scene bring thisdepartment to a new high level. The neweditor is Assistant Professor of Sociology onthe Dartmouth faculty, a former memberof the Dartmouth Athletic Council, and aclose follower, ever since his own varsitytrack days, of all Big Green teams. Prof.Merrill has taught here since 1935 and wason special leave for two years, from October 1941, to do war work with the OPMand the BEW in Washington.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleEXCHANGE EDUCATION

November 1944 By JOHN H. CHIPMAN '19 -

Article

ArticlePLANS FOR SERVICEMEN

November 1944 By WM. STUART MESSER -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

November 1944 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

November 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

November 1944 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS

Francis E. Merrill '26

-

Article

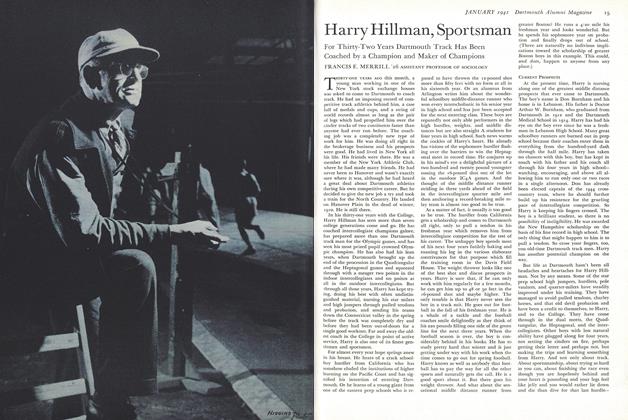

ArticleHarry Hillman, Sportsman

January 1941 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Sports

SportsYALE 6-DARTMOUTH 0

December 1944 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

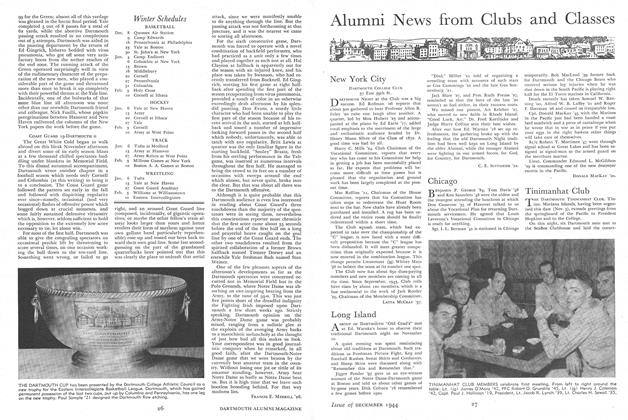

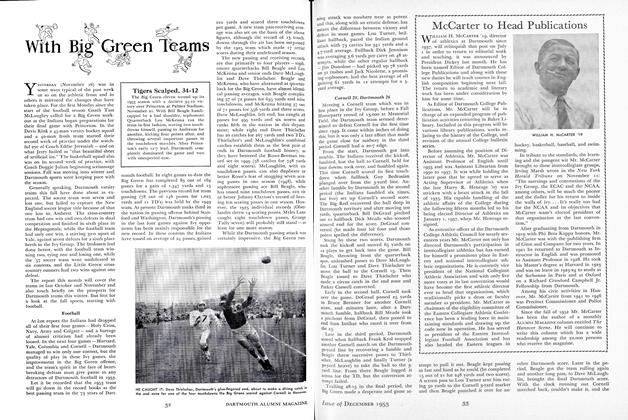

SportsWith Big Green Teams

June 1945 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

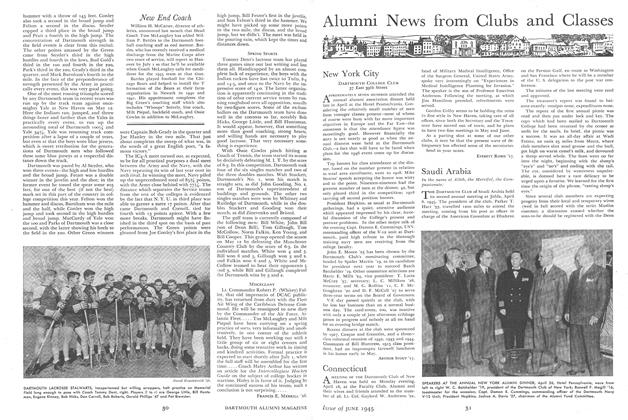

SportsLACROSSE

July 1947 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsHOCKEY

January 1948 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsDARTMOUTH 27, HARVARD 7

December 1950 By Francis E. Merrill '26

Sports

-

Sports

SportsHarvard 3—Dartmouth 0

December 1924 -

Sports

SportsThe Outlook

December 1932 -

Sports

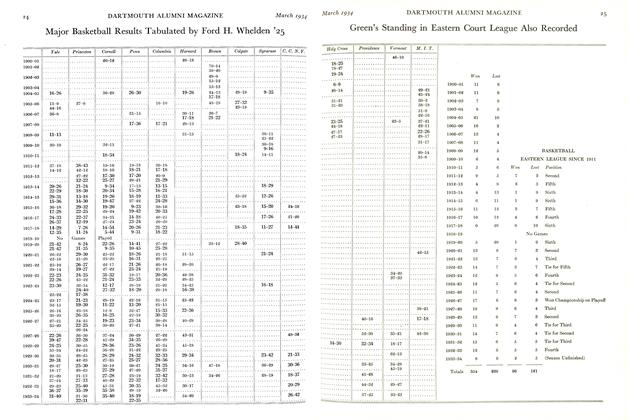

SportsMajor Basketball Results Tabulated by Ford H. Whelden '25

March 1934 -

Sports

SportsCornell 28, Dartmouth 26

December 1953 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Sports

SportsSKIING LAURELS IN DANGER

January 1943 By Elmer Stevens Jr. '43 -

Sports

SportsSWIMMERS FINISH THIRD

April 1943 By J. E. Leggat '45