WHEN I WAS AN UNDERGRADUATE at Dartmouth I commenced my professional career. I couldn't wait to uplift the public! I organized "The Players" and we gave performances in Dartmouth Hall, in Webster Hall and Robinson Hall—sometimes simultaneously. The vogue for the theatre was great on the campus. We even took a company to Boston and New York. We produced everything from Maeterlinck to Synge, including musical reviews. I think we produced twenty plays in all. The one failure was a play I had been inspired to pen. That was my first and last attempt at playwriting.

I left college before completing my fourth year to accept a position as aide to H. Granville Barker, the distinguished actor-producer, who came to this country at the invitation of a group of New York millionaires to revive the "New Theatre," the great Winthrop Ames enterprise on Central Park which was to be our national theatre. Barker was a great man of the theatre, a protege of George Bernard Shaw, a playwright of note, an excellent actor and a truly wonderful stage director. He was, however, committed to repertory, after the continental fashion. Regardless of the success of a play, off it must come and another go on to give variety for the actors and audience.

The moral of this is that it might have been right for London, Berlin, Paris, Munich, Dresden, Vienna and Stockholm but it was no good for New York. New Yorkers, if they liked a play, expected it to run for an indefinite period. And if they didn't like it, a three-day run was too long. Barker, however, was a man of strong will and he had made up his mind that the American public must see it his way or not at all. We finished the season, gave some Greek plays at Harvard, Princeton and a few other colleges, and then Barker returned to England. He had his way but New York didn't accept it.

This taught me a great lesson about communications. I learned very quickly, in a few months to be exact, that if nobody comes to see your elevating play, nobody gets elevated.

I also worked in the box-office during my apprenticeship with a boy called Willie Harris (he is now treasurer for State of the Union at the Hudson Theatre in New York) and I had the opportunity to gather many gems of wisdom regarding the public—gems that Barker had over- looked. And the brightest of these seemed to be the fact that the public is the final arbiter in the matter of a show's success. No producer ever succeeded with an attitude that "the public be damned."

And what does the public want in America today? If we look at our daily papers (with the exception of the ChristianScience Monitor, The New YorkTimes and a few others throughout the country), we are treated to a display of glaring headlines, sensational treatment of stories, "cheesecake" photography, sports, society and the comic sections.

The airwaves are loaded with every conceivable type of show fashioned to please the public taste. These are largely comedy programs; sweet, saccharine serials of home life and love; quiz shows which nobody takes seriously, not even the participants; cowboy and mystery programs. The various popularity surveys undertaken by sponsors indicate that these types of offerings are the most popular with listeners. Broadcasts with a serious purpose are offered occasionally as a public service and fall very low in the popularity ratings.

In the field of literature, 1946 was marked by a best-seller list which many literary critics described as the most mediocre group ever assembled for this distinction. In the words of Time magazine, "a string of novels, most of them with gaudy jackets and tinny texts, sold extravagantly, some of them over 1,000,000 copies apiece."

In short, it appears that the American public has been interested largely in what has been called "escapist" entertainment, charged with limited significance.

Motion pictures, being in business for profit, are produced with a very sensitive ear cocked in the direction of vox populi. The job of producing a picture is a complete gamble (with often more than a million dollars at stake) that the producer has interpreted correctly the public's current likes and dislikes.

In a sense it is a tribute to some producers in Hollywood that they have extended this gamble to the point where they have undertaken subjects on the motion picture screen whicil are considered ahead of the public, if the latter's taste in other media of communication be taken as a criterion.

And, it seems to me, that there is great hope for the future in the fact that the public has responded to some of these efforts in a manner indicating that those who control the various avenues of communication may be underrating people's taste and capacity for appreciating more serious entertainment fare.

Yet I don't see how any fair-minded person can blame motion picture producers for avoiding subjects on the screen which might be "over the public's head." If there were any way of determining how high "over the public's head" one might go, there are, I believe, many producers who are anxious to take the chance. But, in a business where a wrong guess can mean financial disaster, the producer is inclined to follow well-trodden paths in his choice of screen subjects.

For, unlike the press and radio, the screen exists wholly on the capric'es of the theatre-going public. It has no advertising income, no forms of subsidy, but derives its income solely from the nickels and dimes of people all over the world.

Yet the screen is constantly striving to improve its product and has made remarkable strides since its early efforts. Several recent motion pictures, notably Samuel Goldwyn's production, The Best Years ofOur Lives, and Laurence Olivier's HenryV told their stories in a mature and intelligent fashion which has found great favor with the moviegoers. This has encouraged Hollywood and future productions will represent a more mature point of view, a greater willingness to deal with the realities of life.

Another harbinger of improved screen fare is a movement in Hollywood to experiment with films budgeted so low that they may be profitably aimed at a limited audience. These pictures will be shown in small movie houses where they will play extended runs. A case in point is the recent British importation, Noel Coward's Brief Encounter. Exhibited first through normal channels, the picture promised to become a dismal failure. With no stars and a quietly serious story about two middleaged people, the picture had none of the ingredients which spell the wide box-office success which the mammoth movie palaces require in order to meet their overhead. Then a new method of presentation was tried. The picture was booked in small, intimate houses which catered to the intellectual moviegoer seeking more than the usual escapist fare. The picture promises to become a great financial success with this new method of exhibition, indicating that there is room for a "limited editions" approach as well as the customary "best seller" technique of film presentation.

Of all the communication media, the screen is perhaps the freest. Almost any one with talent, a story and/or a cast or director can make a motion picture. Finances are readily forthcoming since banks and investors have learned that motion picture making is an enterprise which rarely fails to the point where the original investment is lost, even though the producer, who is last in line for his money, goes broke.

While the major producing companies are the most important element in picture making, they do not by any means constitute a monopoly. There are several companies organized to distribute the pictures of producers independent of the Big Five. United Artists, for example, distributes only the products of independent motion picture makers. More than seventy independent producing firms exist in Holly wood and more are being established every day. As a matter of fact, there is a growing tendency to break away from the major studios with important actors, directors, producers refusing major studio contracts in order to set up their own producing companies.

Actually the only thing affecting freedom of the screen is censorship. Hollywood has its self-imposed censorship code, administered by the office of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, under the leadership of Eric Johnston. In 1922, the industry wrote its own production code which deletes anything from pictures which might prove to be distasteful or insulting to foreign countries or minorities or particular professional groups; have a bad moral effect on audiences; or impair the morals of minors. Some have argued that the Production Code has been administered in such literal fashion that it, in itself, is an important barrier to freedom of expression. These "may take encouragement in the fact that the Code is not an arbitrary set of laws and that it may be appealed to by the individual producers with some special case. Recently, for example, the Code was amended for the first time in many years to permit the making of a motion picture about international cooperation in the control of illicit drug traffic.

The latest attempt to censor the screen is a much more serious one. It concerns itself with the type of films which should be exported from Hollywood to the foreign market.

Because the motion picture has developed such an international audience, there has recently been a great deal of talk about the impact of the American film abroad and its possible effect on our foreign relations. During the war, the Office of War Information indicated that certain pictures made in Hollywood were giving aid and comfort to the enemy by discrediting our domestic democracy, attacking the morale of people in occupied countries, and even disturbing our own troops abroad. Accordingly, producers were invited to submit their scripts to the OWI for suggestions about avoiding such incidents. In line with millions of other Americans, Hollywood producers cheerfully sacrificed their basic liberty of expression in deference to the exigencies of war.

With war's end, however, vigorous charges were made that Hollywood was now hindering postwar rehabilitation and America's role as a participant therein. It was suggested by some that the State Department or some specially created bureau examine all films designed for export and order the removal of everything which in the opinion of that department might be inimical to America's interests in foreign lands. This worries most motion picture makers and all liberal thinkers who are concerned with protecting freedom of expression. They look upon such possible Federal censorship as an opening wedge which may ultimately affect not only the screen but the radio and the press as well, endangering the basic tenets of a free speech, a free press and a free screen.

Consider, for example, a Hollywood which makes pictures expressive only of the policy of the party in power. Is this not likely to weaken a democracy whose strength lies in the ability of the people to disagree with its government and to express this disagreement?

Those who argue for censorship of American films going abroad do so entirely on the basis of content, arguing that motion pictures are a great educational force and that there are many things about American films which even if they are true in American life, should not be dramatized to our sister nations via the screen.

Let us see what would happen if their purpose could be achieved. First, in selecting the elements which might be irritants abroad, we would have to delete from our pictures about America such things as racial prejudice, unemployment, poverty, crime and all the other unattractive aspects which vex our nation as well as all other nations in the world.

Then, what will the average censored product from Hollywood look like in Europe, Asia and Africa?

Obviously, we shall have to return to the early days of motion picture making when the screen told stories set in some Never Never Land, with no relation to life and no recognition of the practical realities of modern living. We shall tell stories of high romance and adventure set in periods so far removed that these could not conceivably be a reflection of America today. We shall have to make musical comedies which will depend entirely for their appeal on pretty girls and pleasant songs. We might add to these, bedroom farces and other light fare which by their very meaninglessness will be unlikely to tell our neighbors anything about us which might be disturbing—which will tell them, as a matter of fact, nothing at all about us.

In the meantime, how will this affect our movies at home? There can be little doubt that the motion picture screen on occasion has been a tremendous moral force in the education of our own American public. The gangster film, for example, displayed the underworld in all its brutal highlights, contributing thereby to a general public revulsion which criminal authorities have credited as an important factor in the ultimate destruction of prohibition era gangsterism. A picture like the Oxbow Incident was a forceful antilynching argument; Grapes of Wrath and Tobacco Road carried the news forcefully to people all over America that there are in our country little islands of poverty, filth and depression amounting almost to a national crime.

With federal censorship, the American moviegoer will have to be penalized to the extent that he will see no more films of this type. It has already been indicated that no picture can be profitable with returns from the domestic or foreign market alone. So if "escapist" films are considered safest for foreign export, then this will be the character of the program at your neighborhood movie.-It may be that time will bring about changes in the economic structure of the motion picture industry which, by a reduction of costs, will permit the making of pictures especially for the home front and others particularly for export. Until that time Hollywood must, if it is to survive, make its pictures to please all markets.

It should be obvious to anyone who has had experience in mass media, who really wants the people to know and does not believe in a "Celluloid Curtain," that the effect of showing all types of films must be to lead the people of the world to the conclusion that democracy does work, that only a strong democracy can afford to make this self-critical product for entertainment under a capitalistic system.

Would it be better to show ourselves to our allies and erstwhile enemies as perfect men and women with none of the failings of other peoples; to show us as a nation of Supermen with none of the ordinary faults of a developing society; to show the United States as a sort of an Erewhon, a Utopia where nothing ever goes wrong?

This, by no means, is an argument that only films of the type of Grapes of Wrath should be sent abroad. Hollywod is aware that it must increase its efforts to make pictures which show more of the desirable and admirable aspects of our democratic system. Yet it must be recognized that it is because of our honest and uncompromising position in portraying ourselves and exhibiting every kind of picture that we have earned and kept the goodwill and support of the greatest audience ever assembled by any medium of communication.

Efforts to improve Hollywood's product cannot be helped by censorship of any kind. Censorship as it exists today with pressure groups and local and state censorship boards is obviously not justified by any constitutional concept of freedom. It should be limited to considerations of bad taste, not material content. I would heartily welcome the system used in England the segregation of films into two classes—those for adults and those for children. This would allow greater freedom of expression by preventing children from seeing adult subjects.

In place of federal censorship, it would be valuable to establish an adjunct of the State Department which will serve to keep producers informed of the world picture. If certain Hollywood pictures present a fake portrayal of postwar America, this is due either to ignorance or even stupidity on the part of some producer. I know of no producer so venal that he will deliberately embroil or embarrass this country in its conduct of foreign affairs. tiVy cK

Most producers are aware of their; responsibility in speaking to the world today. Many of them are worried about it and are groping for the knowledge and information which will help them avoid any serious errors. The government has through its various public relations channels long serviced the newspapers and radio stations along these lines, relying upon the judgment and goodwill of the publisher or broadcaster for assistance in spreading the word. Hollywood too may be depended on if it is similarly treated.

As a matter of fact, Hollywood recently organized the Motion Picture Export Association which is an attempt at self-regu^ lation in culling from films sent abroad any pictures which might be glaringly offensive to other nations or embarrassing to our diplomatic activities.

Censorship and the right of all people to know are contradictory terms. If we are to maintain freedom of expression, not only for the screen but for all communication media, then we must rely upon a wellinformed group of propagandists and the word is used here without any of its acquired connotations—to disseminate information through their respective media and an alert public to discredit any of these when they have failed to do the task honestly and effectively.

I have great respect for the public, especially as it operates in a democracy. When it doesn't like a thing it ultimately gets around to doing something about it. It will play an important role in shaping our film future for no medium is as sensitive to the people's displeasure as the motion picture screen.

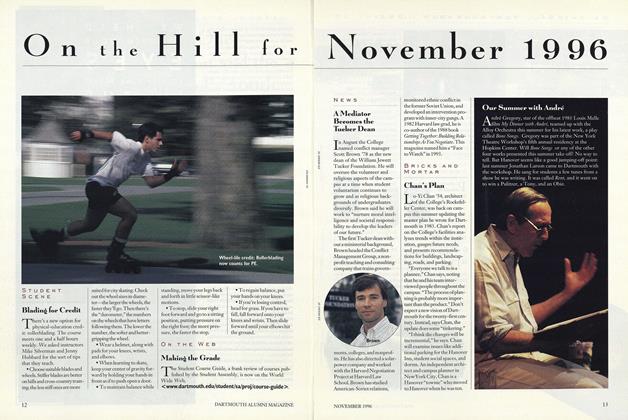

ONE OF AMERICA'S BEST KNOWN MOVIE PRODUCERS: Walter Wanger 'l5, widely recognized as a progressive influence in the motion picture industry, poses before a portrait of his daughter Stephanie.

Among leaders of the motion picture industry, Walter Wanger '15 is outstanding not only as a producer but also as a progressive influence. The fact that he was elected President o£ the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for six consecutive years indicates that Hollywood is aware of his special talents and of his intelligent grasp of the role of the movies in our national life. Mr. Wanger has constantly fought for a greater sense of responsibility on the part of the movies, and has urged more courage in dealing with contemporary events. Mr. Wanger has been connected with the motion picture industry since shortly after World War I, in which he served as a member of Fiorella LaGuardia's aviation unit on the Italian front. After top production jobs with Lasky, Paramount, MGM and Columbia, he established his own company, Walter Wanger Productions, in 1934 and now has his film headquarters at Universal Studio, Universal City, California. Mrs. Wanger is the screen actress, Joan Bennett. Since Dartmouth days, when his theatrical interests got their start, Mr. Wanger has kept in close touch with the College. He served as President of the General Alumni Association in 1944-45. Dartmouth's course in motion picture writing was established with Mr. Wanger's help and he has also been a generous contributor to the Irving Thalberg Memorial Library of the Motion Picture, one of the best collections of scripts in existence.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCharles Edward Hovey '52

April 1947 By ALLAN MACDONALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleA Challenge Still Unanswered

April 1947 By BUDD SCHULBERG '36 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1947 By Charles Clucas '44 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1947 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

April 1947 By JOHN H. DEVLIN, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR.