A WHILE AGO, when Harvard decided to do something to make the library lives of her undergraduates bearable, a pertinent promotional document was smuggled into Hanover. The sight of it caused some local eyes to stand out so far that you could have knocked them off like icicles, with a cane. It was a chart displaying the relative total undergraduate library expenditures of a number of institutions, in which the rigors of pure intellectual endeavor are ameliorated with festoons of ivy. A cherry red column indicated Harvard's library budget for undergraduates. A little farther along, Dartmouth's column, in modest gray, towered far above all the rest—to represent more than three times the Harvard total of dollars.

There was, of course, a gimmick. When this was explained, the popping eyes plopped safely back into their sockets. Harvard's 175,000 column represented that minor estimated portion of the whole University library expenditure, which could fairly be said to apply to undergraduates as contrasted with graduate students and faculty. Nevertheless, it was one of many reminders that Dartmouth has the largest, and in many respects the finest, undergraduate library in existence.

This is a privilege and a blessing, but it carries with it the obligations of eminence. Harvard's new Lamont Library, successfully opened a few weeks ago as a New Year's gift to the undergraduates of the Yard, is a reminder of another sort. Baker has come of age—21 years. We're still much bigger than Lamont is ever intended to become, and thereby dangles a distinction. Bigness can be a disadvantage, as the dinosaur, despite his extra brain aft, appears to have discovered in due course. Consequently the complexion of the Dartmouth College Library's activities has been altering, over the last few years, in ways that are calculated to adapt it more efficiently to the needs of modern learning and teaching.

The most evident structural change is the Public Affairs Laboratory, which occupies a partitioned half of the large basement reading room in the corner nearest Webster Hall. This is an experiment in maximum faculty-library cooperation for inten- sive use of specific, selected materials having the highest degree of pertinence to the work of one particular course: Great Issues.

Visual aids, chiefly in the form of walldisplays, are stressed particularly at this point in our total operations, but they have been introduced elsewhere increasingly. All up and down the building, sedate teachers and staff members are having a lovely time drawing with colored inks, broad lettering pens, bright-headed map pins, and the kind of red tape that really comes on spools. (In the undergraduate view, there is still too much of the other sort. Just let them wait until they have to use some other libraries we could name!)

Over in the east wing, a recently enlarged and relocated map library is run by a pair of escapists who consider it their business to keep the walls and tables covered with bright, alluring maps and pictures of places where one would passionately like to be, on a day like this: Teneriffe, the Bahamas, Tahiti.

(Not that it's cold. As somebody may have told you, Hanover is having its weirdest winter since 1936 January dawning in a warm drizzle of rain. Under your respondent's window, this midwinter morning, the sprouting irises are six inches high. That buzzing sound on Main Street is the confraternity of sporting-goods dealers, sawing their skis into bows and arrows, for a new start.)

The main emphasis of Library planning, these days, in Hanover, is toward a more efficient and effective use of what is on hand. For the purposes of encouraging a fine faculty to become an even better one, we cannot have too many books—provided they are selected with discrimination. But for the uses of undergraduates, we have to be alert to every means of separating out from the growing bookstock the particular volumes that are most pertinent. To expedite planning along these lines, an Educational Office was set up in the Library three years ago, with George Wood, Professor of Belles Lettres, in charge. It is wide open to new ideas. If you have any, send them to George, or to the undersigned.

The Tower Room Exhibits have been particularly vivid and impish, lately, with posters and other display devices done by a most skillful hand. This is called for, to offset somewhat the steady pressure toward making a recreational room into a study hall. Confronted by this tendency, we are in a fine dilemma. If we insist that the room be put to the use for which it was designed—voluntary reading—we appear to be opposing the primary orthodox business of a Dartmouth education: the required work for a degree. If we encourage more studying, wherever and whenever the young gentlemen of the college choose to devote themselves to so unlikely an activity, anyone trying to make the intended use of the room is in a large measure prevented from doing so. The books are in alcoves. When students with notebooks and other paraphernalia are ensconced in the big chairs, stockinged feet resting on an adjacent shelf at head height, the chance to browse in that particular alcove is severely diminished.

A year or two ago, seeking a way out, we dropped a hint in The Dartmouth. A course for credit, in which a man would devote, say, nine hours a week to exploring among good books at his own adventure, might be the answer. Prerequisite: a sense of responsibility, proved by good grades in other courses. The student would take his chances, for a final grade, on a carefully-kept journal of his reading.

The next thing we knew, a petition for the establishment of such a course landed on our doorstep, with 96 names signed to it. The reason for mentioning it here is this: It would be useful to know what happens to the alumnus who, when in college, faithfully reads only what he is specifically required to read. Is the habit of voluntary reading of good books likely to be acquired after graduation, by those who have put it off so long? May we have some testimony, or confessions, on that score?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesD. N. A. A.

February 1949 By MAX PRYOR, J. FREDERICK PFAU III -

Article

ArticleThe Indian Sharpens Up His Gridiron Tomahawk

February 1949 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

February 1949 By ROBERT P. FULLER, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

February 1949 By HENRY R. BANKART JR., FREDERICK T. HALEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

February 1949 By OSMUN SKINNER, RUPERT C. THOMPSON JR. -

Class Notes

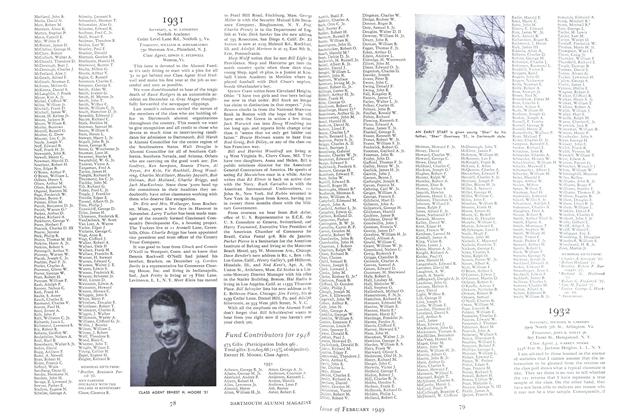

Class Notes1931

February 1949 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI