by John Varney 'op.The William-Frederick, Press, 313 West 35thSt., New York 1950; pages 47; $l.OO.

In the five parts and fifty numbered sections of this poem, the writing of which extended from November of 1948 to May of this year, Varney has struck out a new style in the writing of satiric-critical poetry. The verse is compact, elliptical in phrasing, and, until one gets the hang of it, almost spondaic, the lines seem to move so slowly with their freight of long syllables. The content, too, does not make for easy reading; there are certain recurring symbols which are—some of themelusive in meaning; and the verse is packed with allusions to circumstances in the career of the writers (mostly modern poets) whom it criticises. But the perservering reader will be rewarded by many bits of shrewd observation and flashes of idiosyncratic humor, and will perceive in these lines the alert and instructive mind of their author.

Varney passes in review certain major figures T. S. Eliot, E. E. Cummings, Wallace Stevens with incidental references to others from Yeats and Rimbaud to the present. Against a background of modern philosophy, science, and art, he poses his main figures as exemplars of an inbreeding, too highly self conscious, and essentially decadent though peacockishly seductive art. Yet the characteristics of these writers are only in part selfwilled; they are characteristics of our civilization, of which they are spokesmen. Varney looks forward to a future in which, by means not too clearly defined, art will become at once simpler and more varied, and a center of affirmation and unity for the whole community of mankind, instead of being, as it is now, both product and promoter of a lack of imaginative fellowship between the "levels" into which men have become stratified.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFINIS

October 1950 By Bernard G. Sykes '51 -

Article

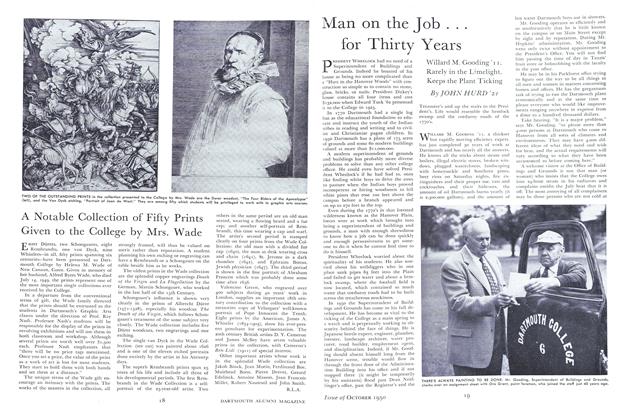

ArticleMan on the Job . . . for Thirty Years

October 1950 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, JULIUS A. RIPPEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

October 1950 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL -

Article

ArticleTHERE'S METHOD Behind the Fall Madness

October 1950 By ROGER K. WOLBARST '43

F. Cudworth Flint

-

Books

BooksSADDLING PEGASUS

JANUARY 1932 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksBEAU-POIL AU MAROC

June 1940 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksBROTHERHOOD OF MEN

July 1949 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksAN HERB BASKET,

March 1951 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Books

BooksTHE WORLD, THE WORLDLESS.

JUNE 1965 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Books

BooksTHE GEORGIAN REVOLT: RISE AND FALL OF A POETIC IDEAL, 1910-1922.

NOVEMBER 1965 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT

Books

-

Books

BooksShelflife

May/June 2005 -

Books

BooksDAEMON IN THE ROCK.

June 1934 By Alexander Laing -

Books

BooksMaverick

May 1980 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Books

BooksFREEDOM OF SPEECH BY RADIO AND TELEVISION.

APRIL 1959 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksNotes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief.

March 1979 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksHIGHLIGHTS OF MODERN LITERATURE.

May 1954 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24