A Review of "The Unconquered," Last Novel of Ben Ames Williams '10

December 1953 KENNETH ROBERTS '34hA Review of "The Unconquered," Last Novel of Ben Ames Williams '10 KENNETH ROBERTS '34h December 1953

ON November 3, 1953, in the ancient whaling city of New Bedford, Massachusetts, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presented the World Premiere of Ben Ames Williams's novel, Allthe Brothers Were Valiant. That was Ben Williams's first book. It was published in 1919. Thirty-four years had to pass before the admirable qualities of his story were fully recognized and again brought to life in dramatic color-film, to stand with those other great and simple tales of sailors and the sea, Captains Courageous and Treasure Island.

In 1953, Houghton Mifflin Company published Ben Williams's last work, The Unconquered, and it seems to me that this great book is in danger of encountering the same delayed recognition that haunted All the BrothersWere Valiant for a third of a century. There has been a sort of literary fashion among egghead book reviewers to damn Ben Williams's magnificent array of novels with faint praise or downright misrepresentation. Critics who can find something admirable in William Faulkner's tortured, clumsy, endless sentences, or in T. S. Eliot's baffling, obscure words, are greatly given to implying that Ben Williams's novels are without imagination: that he writes to a standard. Of each one of his books these superior reviewers are inclined to say that it's "standard Williams, with the familiar faults, the familiar virtues."

Nothing could be farther from the truth. Of all novelists, Ben Williams was least standardized. He turned from one style of writing to another with a rapidity that,annoyed magazine editors and book publishers, and with a complete disregard for the results of those changes on his own fortunes. His early stories of Maine, eagerly awaited by the editors of the Saturday Evening Post, were succeeded in bewildering rapidity by tales of whaling, of Newspaper Row (Splendor), of the Revolution, of the War of 1812, and of the South at war and during Reconstruction, of which The Unconquered is the climax. The editors of the Post and other publications now found that they couldn't publish Ben's books unless they changed the shape of their magazines to conform to those which printed the works of Charles Reade and Charles Dickens. They had on their hands an author who sprawled all over the place who knew important things about important periods, and was insistent on telling all he knew.

They were pained by this kaleidoscopic change of pace on the part of a contributor who had seemed to them as dependable in the production of standard-length fiction as Kipling or Robert Louis Stevenson. They attempted to reason with him. He was, they pointed out, kicking over the traces. Inevitably he would tangle with the whiffietree and break a leg.

Ben only laughed at them and went on writing what he wanted to write long books, far too long for magazine serialization: books carefully conceived, tirelessly studied, endlessly imagined and rewritten, but by eggheads brushed off as unimaginative.

No imagination in Ben Williams's books? Oh, come now!

I was having trouble with a woman character, when I was writing Oliver Wiswell, and I complained to Ben about it. "I'll tell you what I thinks the matter," Ben said. "I don't believe you know enough about her. Get to know her well, and she'll come to life all right. Drop the book for a while and spend a few weeks writing about her. Write about her father and mother, and her days as a child and as a young woman 30,000 words, maybe, just about her. Then throw 'em away and go back to the book."

I cannot conceive how anyone, even an egghead, can think there's no imagination involved in the creation, in The Unconquered, of the character of Lucy that wholly lovable young lady who, seeing the faults of the South through eyes as clear as those of her Kissing Kin were befogged, cried out that she hated the South and everything about it. She appealed to her father, "But Papa, can't we go live somewhere where people aren't always killing people and being proud of it?" Her father, cut from the same cloth, agrees ruefully: "To kill a man anywhere in the South isn't very serious; not if you've any excuse at all... and of course you don't need an excuse to kill a nigra."

Who dares to say that imagination is lacking in the Mechanics Institute Massacre in that shocking series of scenes describing the cold-blooded murder, the bludgeoning to a pulp, of masses of Negroes and "nigger lovers" by the sterling citizenry of New Orleans, abetted and aided by a police force that would have commanded the respect and admiration of Jacob Malik and General Nam Il? No imag - well, really!

It was the finest sort of imagination that brought infuriatingly to life Lucy's alley-cat of a mother, who, "with her many words held them all for a while in silent misery." Dear, delightful Enid, lecherous, dirty-minded, mealy mouthed, a Southern belle to end all Southern belles: a brainless idiot, gaily amused and proud at the thought that her Negro maid had, thanks to the precocity of her 14-year-old son, become pregnant. Equally revolting is that same charming little Peter, a murderer and a monster at a period when reefers and hot rods were half a century away.

Perhaps the bigness and the quietness the terrible quietness —of The Unconquered is the quality that baffles egghead critics. All the sentences are crystal-clear, and the words are simple, as Ben Williams intended them to be. Those faults are common to all the world's great writers, but glaringly absent from the works of too many American recipients of the highest literary honors. Ben once explained to me his reasons for thinking he would never be elected to the American Institute of Arts and Letters, a society which ostensibly exists to honor those whose work in literature has been outstanding and no author was more deserving of election than Ben Ames Williams, with his thirty-eight splendid novels. "I have persisted in consciously trying to do something I wasn't sure I could do," Ben wrote me: "I have never settled into a groove: never used words that an ordinary person has to look up in a dictionary: never, if I could help it, let vice triumph over virtue. My case, I'm sure, is hopeless. Don't bother to propose me for membership, ever again."

His case was hopeless, but that fact did nothing to detract from the stature of his books or the integrity of his monumental labors: it merely emphasized that the American Institute of Arts and Letters had unfortunately fallen short of the goal announced when it was founded in 1898 by such American literary giants as Henry Adams, Mark Twain, Bret Harte, John Hay, William Dean Howells, Henry James, Henry Cabot Lodge, Charles Eliot Norton, Theodore Roosevelt, and Woodrow Wilson.

No such level-eyed, completely truthful study of the poisonous effect of slavery, war and mob politics on the South has ever been written or even attempted; but in The Unconquered Ben Williams captured it completely.

The "unconquered" are the conscienceless rebel remnants of the Civil War who, like so many peoples, past and present, preferred to destroy enemies, friends and themselves, rather than live at peace with their neighbors. Their story is woven from cotton, grafters, swamps, quick profits, cottonseed oil, nigras, nightingales, Northern soldiers, Basin Street bordellos, toddies, scoundrels and rogues: from mistresses yellow and white, Southern gentlemen who make the flesh crawl, plantations abandoned by whites too lazy or too proud to do their own work: from the all-pervasive "moisture of New Orleans, like greasy dew," the barred windows of the Creole aristocracy: from Northern adventurers greedy for loot, political tricksters, bigoted abolitionist churchmen, and countless other Southern materials, most of them repulsive but never threaded so profusely into any canvas that purported to portray events below the Mason and Dixon line.

Ben, a Mississippian by birth and a State-of- Mainer by choice, thought he'd be banned excommunicated from the South for writing all the knowledge he had acquired by virtue of his researching ability, which was that of a great reporter, plus his inherited judicial temperament, and an acquired New England distaste for poseurs and for concealing curtains of magnolia blossoms.

The South, he thought, couldn't accept with equanimity such a description of post-war conditions as: "Louisiana and New Orleans are bankrupt, their obligations selling at twenty-five cents on the dollar. There are only four paved roads in the city, and prolonged bad weather makes our other streets all but impassable. We've the finest harbor in the world and not one good wharf. Open ditches stinking with foul waste are our only drainage. Our streets are lined with gambling dens and the houses of harlotry. Epidemics regularly kill their scores and their hundreds. New Orleans is controlled by a corrupt, ignorant and bloody-minded gang. The public buildings are in disrepair, the levees are crumbling. The police force is recruited from the ranks of thugs and murderers, and if there is an honest public official in the city, I don't know him. We have no clean water to drink; swarms of flies; no screens; filthy slaughterhouses! The city is fouler than a well-kept cesspool."

"When this book is published," Ben told me, after he had passed the half-way mark, "I'll never be able to go back to the South again." He was wrong, because present-day Southerners admire qualities that once were anathema to most of them; but even though he had been right, he would have kept on without softening or concealing any part of the dreadful picture he had to draw —of murder as a political weapon, for example: of "thousands and thousands of Negroes, huddled in closed and shuttered rooms like frightened animals in their dens, whispering their fears in trembling tones": of the appalling ignorance of blacks and whites alike; of the seeming gentleman who confessed horribly that never once in his life had he done any single thing as well as he could. Never once!

The masterly transition of the Maine-born Captain Page and his lovely bride from the "greasy moisture," the poisonous atmosphere, of New Orleans to the clean, clear, heartening hills and forests and farms of Maine in those days before every roadside was contaminated and defiled by monstrosities placed upon them by cheap and greedy people, brings a catch to the throat and tears to the eyes of those who have known unspoiled New England in the spring, in the winter and in the autumn.

"Autumn was a time of beauty blazing bright, yet quick to fade and vanish in a shower of falling leaves. It was the time to make the house secure, to fill the shed with wood and the cellar with supplies; salt pork and bacon put down in crocks of brine, potatoes in their bin, apples in their barrels, beets and pumpkins and squash for the humans in the house and the creatures in the barn. With October a third gone, beauty filled the world; ten days later the trees were bare, stripped for the winter's battle against cold thai burned like fire."

No review, restricted as such inadequacy must be, can do justice to this book

I'm proud of my personal bookshelf-of those thirty-eight fine novels by Ben Ames Williams, with All the Brothers Were Valium on the left, to guide on, and The Unconquered as a giant flanker on the far right separating Ben's books from those of Booth Tarkington and Mark Twain, of Kipling and Stevenson and John Marquand mighty proud; and so, I am happy to say, is Dart, mouth.

THE UNCONQUERED. By Ben Ames Williams '10. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1953.689 pp. $5.00.

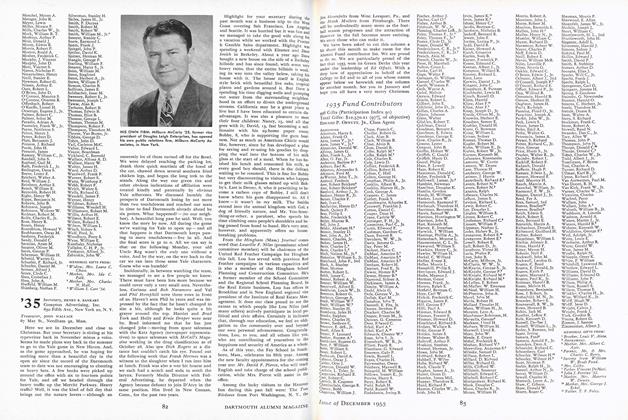

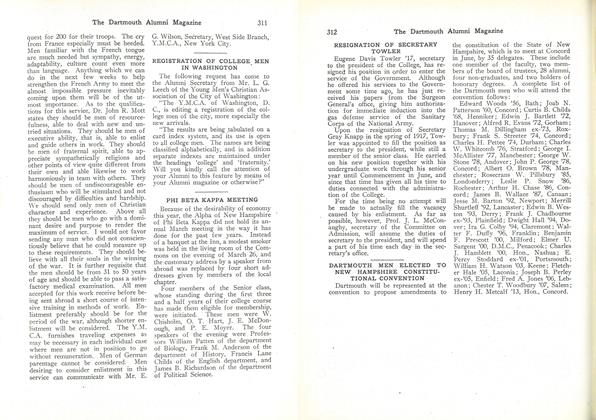

FELLOW NOVELISTS: Kenneth Roberts '34h (left) and the late Ben Ames Williams '10, who were close friends, shown at Mr. Roberts' home in Maine. The two snapshots were taken only a few moments apart, as the writers relaxed on a summer day.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleBIGNESS

December 1953 By DAVID E. LILIENTHAL -

Article

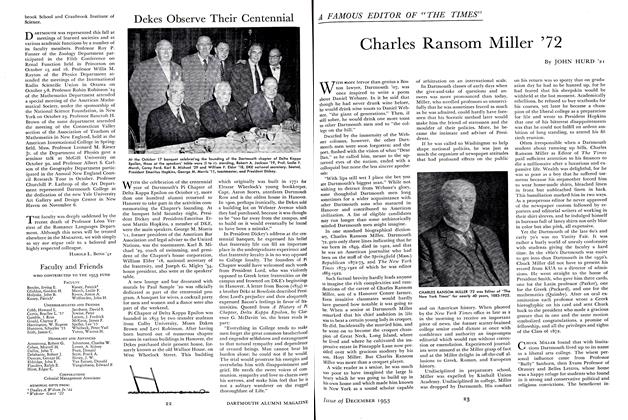

ArticleCharles Ransom Miller '72

December 1953 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, w. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1953 By HENRY R. BANKART, JOHN WALLACE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

December 1953 By Lambert & Feasley, Inc., PETER B. EVANS, CHARLES S. MCALLISTER -

Article

ArticleA True Dog Story

December 1953 By A. I. Dickerson

Article

-

Article

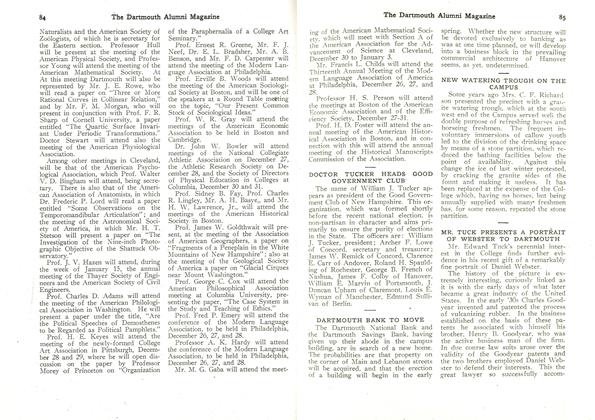

ArticleDOCTOR TUCKER HEADS GOOD GOVERNMENT CLUB'

-

Article

ArticleRESIGNATION OF SECRETARY TOWLER

April 1918 -

Article

Article1938 Enrollment

October 1938 -

Article

ArticleAdmissions Assistant

January 1946 -

Article

ArticleThayer School expands arctic research

OCTOBER • 1986 -

Article

ArticleButton Cops 2nd Emmy with Philly Promo

FEBRUARY • 1988