WHILE the weather outside is frightful, life in Hanover hits a fever pitch in early February. It is the time of the Great Marathon. Jazzed up with coffee and No-Doz pills, students trudge sleeplessly through murky snow drifts and murkier final exams. Simultaneously they pack snow, scrounge rooms and tickets, and keep telephones jangling. Winter Carnival approaches.

This is mid-point in the College's 185th year. Finals climax its most important aspect, the academic. In retrospect, these have been the notable academic events to date:

¶ The best postwar freshman class, statistically speaking, entered the College; ¶ The growing crop of new teachers was tried, found waiting in some cases, but was stimulating for the most part; ¶ The teaching intern program added more youthful zest to the faculty; ¶ The basement of Silsby Hall proved too small, one pre-Christmas evening, to hold a crowd gathered to hear Professors Gramlich, Hastorf and Berthold chew over "Contemporary Psychology and Its Impact on Religious Thought." This meeting, sponsored by the newly formed Psychology Club, was perhaps the half-year's major academic event. The size and rapt attention of the audience disclosed an interest in "higher education" that is more widespread than popularly supposed.

Viewed in broad perspective, the curriculum remained venerable and complacent. Some young blood was added, some recently new courses took on a permanent air, but there were few experiments and hence no outright failures. Some dim but unmistakable signs of restiveness are discernible.

Just as finals this week mark the college year's academic mid-point, so does Carnival mark its social mid-point. At press time, mystic signs of the North bode ideal skiing, skating and sculpturing conditions. The statues will materialize, as always, in a last-minute splash of water buckets. Outdoor Evening is, as always, ballyhooed "better than ever." The teams are, in truth, better than ever. So if recent measures to fend off invading, free-loading mobs work out, Carnival will be the nation's finest college weekend — as always.

And more decisively than ever, Carnival will serve as a barometer to record the temper of the College's social life. For if there is growing restiveness toward campus academic life, it is no overstatement to say a volcano of controversy is boiling around its social life.

Alumni are now familiar with the first eruption: President Dickey's WDBS broadcast, which was reprinted in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE last month. The speech necessarily challenged a blissful status quo, and its vague terminology called for the broadest inferences. For these reasons, initial student responses ("I'll never send a son of mine to Dartmouth," etc.) generated more heat than light. But they successfully opened up the whole issue of College social life.

President Dickey essentially did two things in his speech.

First, he announced the creation of a Commission on Student Life and Its Regulation. It consists of four teachers including chairman Frank Ryder, one Administrator as executive secretary and three "community" members, plus four administrative and seven undergraduate officers as voteless "associates." Its job is to probe all aspects of campus social life.

Second, the President aired some views on "positive" and "regulatory" problems. He said freshman dormitories, adult-supervised dormitories and better dorm lounge facilities are worth looking into. And he reasoned that since facilities (presumably for self-government and/or supervision) of dormitories and fraternities cannot be equated, "serious misgivings" arise as to whether their privileges can be equated. "I have in mind particularly," he noted, "the privileges relating to the entertainment of women guests and the use of alcoholic beverages."

Students bent a sensitive ear, sniffed the air around Parkhurst Hall, yelled "Crackdown!" They stared hard through the welter of verbiage, and vowed they saw an Administration drive for more rules. (It already has stepped up enforcement.)

They looked in vain for a justification. The President did not renounce his oftstated principle that a Dartmouth man learns maturity best through his freedom to be immature through his mistakes. The President did not say students have proved unworthy of their freedom. He did hint that changed conditions dictate changed rules ("We should review, and where necessary revise ... in the light of our experience during the past eight years") but gave no clue as to why the push should be toward paternalism. He merely observed a decline in student-veterans and an upsurge of student government.

There was - and there remains - a missing link in the controversy. Here is a new policy, offered without a new problem or an unresolved old problem. President Dickey did not say in public what he confesses in private: he is mighty worried about those recurrent campus "incidents" which blacken the College's name. Moreover, the President seems to feel - and now we're claiming to read his mind - that "getting stewed" is considered a virtue by a substantial minority of students, if not by a majority.

It remains for the Commission to discover if there has been a lethal tilt in the balance between freedom and responsibility. If the College's liberal rules have not been matched by responsible conduct, then freedom must be withdrawn lest the flying beer bottles bring down her walls.

The Commission must compare the "New Hampshire Hall Case" with the general degree of responsibility - with, for example, the fact that chronic offenders, rather than "normal" students, take up the serious time of the Undergraduate Council's Judiciary Committee. It also must compare the facts of offenses in fraternity houses with those in dormitories, regardless of the disparity in facilities.

The most important judgment the Commission must make is this: how important is the independence, the sense of self-reliance, which a Dartmouth student enjoys? Upon this decision rests a consequent decision: how much outside pressure should the College absorb to uphold its liberal policy toward its liberal arts students?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Faculty Policies

February 1954 By DONALD H. MORRISON '47h -

Feature

FeatureTestament of a Teacher

February 1954 By ROYAL CASE NEMIAH '23h -

Feature

FeatureThe Teacher of Social Science and the World Crisis

February 1954 By JOHN CLINTON ADAMS -

Feature

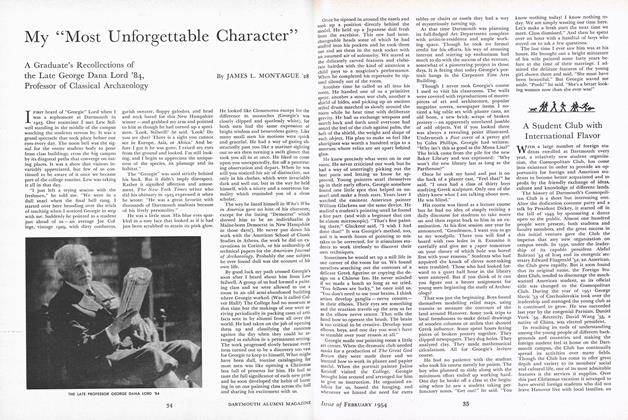

FeatureMy "Most Unforgettable Character"

February 1954 By JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

February 1954 By JOHN A. WRIGHT, JOHN B. WOLFF JR.

DICK MAY '54

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1953 By Dick May '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1953 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1954 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleMilestones

January 1954 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1954 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1954 By DICK MAY '54

Article

-

Article

ArticlePONDER '17 DOWNS TWO GERMAN AIRPLANES

July 1918 -

Article

ArticleBalloting for election of alumni councilors is now in progress

May, 1926 -

Article

ArticleProf's Choice

MAY 1991 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

OCTOBER 1997 -

Article

ArticleMoody Brothers, 1-2 in the Shot

MARCH 1971 By JIM MURPHY -

Article

ArticlePIKE'S ARITHMETIC

April 1926 By Professor Bancroft H. Brown