Memories of Thomas Wolfe and Others

THE publication of The Letters ofThomas Wolfe in October of this year has led me to reflect on the circumstances surrounding my reading of Look Homeward, Angel in the fall of 1929. I was then a freshman at Dartmouth. It was my good fortune to meet Tom Wolfe during the year following my graduation from Dartmouth, when I was a graduate student at Columbia University, through the happy circumstance of our both being in New York City and both having the same editors, Maxwell E. Perkins and John Hall Wheelock, at Scribner's. Possibly the most important of all influences which can strengthen the fledgling writer in his determination to persevere, come hell or high water, along his lonely, difficult course is the literary friendship. I remember vividly the great encouragement which I, as a young writer, derived from personal contact widr professional writers and editors, including Robert Frost, Max Perkins, Jack Wheelock and Tom Wolfe, immediately before, during and after that year.

Since boyhood I have been a voracious and assiduous reader. So it came about that, in September 1929, when I was a freshman newly arrived in Hanover, I gravitated toward the Dartmouth Bookstore. There I bought a copy of the August issue of Scribner's Magazine, and found in it an imaginative and poetic story by an obscure North Carolinian named Thomas Wolfe. This story, which was, in fact, a part of Look Homeward, Angel, so impressed me that I watched for and purchased the novel, the early appearance of which had been announced in that issue of the magazine. I bought one of the two copies of the novel which arrived at the bookstore in advance of publication. Published on October 18, 1929, this book made a tremendous personal hit with me.

I must have felt the strong appeal of poet talking to poet, young romantic talking to young romantic, for I typed out a long letter of praise, properly humble, to Thomas Wolfe about his first book. I did not expect, and indeed never received, a reply to this communication, but several years later, when I met and became friendly with Wolfe, he told me that he remembered having received it, and that he had been grateful for it, and had intended to reply but never got around to doing so. That my letter played any part in bolstering the Wolfe ego in a difficult time, I doubt, but I am glad that I expressed my whole-hearted appreciation of this fine book to its author at the time of its publication.

I was encouraged that fall of 1929 by winning first prize in the Dartmouth Undergraduate Poetry Contest. Edna St. Vincent Millay, whose poetry I had long admired, made the announcement following a reading she gave in Webster Hall. I was deeply moved by her sensitive, compassionate and utterly simple rendition of her own poems; when I met her afterward I was entranced by her as a person.

There followed congenial and stimulating associations with friends, writers and non-writers, both in New York and among the faculty and student body at Dartmouth, the winning of other contests, such as the Glascock Intercollegiate Poetry Contest at Mt. Holyoke College, and the publication of some of my poems in magazines here and abroad.

Outstanding among my kindly friends and mentors while I was an undergraduate was Robert Frost. I met Frost through Harold G. Rugg, inspired bookman and bibliophile, then on the staff of Baker Library. In the fall of 1930 there was published a collection of Dartmouth Verse written by undergraduates for the contest of the preceding fall. After sending Frost a copy of the anthology, I received a superb letter from him, which began: "The book has come and I have read your poems first. They are good. They have loveliness - they surely have that. They are carried high." This letter, dated October 26, 1930, and sent from Amherst, concluded as follows: "You'll have me watching you. We must meet again and have a talk about poetry and nothing but poetry. The great length of this letter is the measure of my thanks for the book."

Frost did keep his eye on me as he had promised. From time to time I sent him poems of mine as they were published. In 1932-33, my senior year at Dartmouth, I was very fortunate in being awarded one of the first Senior Fellowships which President Ernest Martin Hopkins, acting on his wisdom, experience, and insight, founded in that year in order to free a handful of talented students at the College from the drudgery of routine class work and comprehensive final examinations. Wonder of wonders, I was free to devote much more time to writing, and my tuition was paid!

Before graduation in that bleak Depression year, 1933, I applied for and was awarded a Graduate Residence Scholarship in the Faculty of Philosophy at Columbia University, for the purpose of taking graduate work in English and Comparative Literature. By late May, 1933, I had evolved a plan for my first book of poetry, Avalanche of April, a celebration of youth and spring in New Hampshire, and had written most of the book. I had sent all this poetry to Frost as it was published here and there in the magazines. Now, on May 21, Frost wrote to me asking "if we could see each other for a talk about poetry at Hanover around Commencement." He did not hint that he was to receive an honorary degree. Coyly he said in his letter: "I have half a mind to re-visit the old college at about that time."

On May 30, Frost wrote: "I can say with all my heart that this last you send me is fine poetry, high and exciting. Till we meet!"

At Commencement, Frost and I had our talk. As I recall, he told me that I was now ready to have my book published. I graduated with the Class of 1933, reading the Class Poem. Frost was presented with an honorary degree. Most generously he gave me a photograph of himself inscribed to me as his "friend in the art," and an inscribed copy of his first book. I was immensely pleased to have the prized sheepskin and these two handsome gifts.

THAT summer Avalanche of April was tentatively accepted for publication by Scribner's, the first publisher to which it was submitted. Meanwhile, John Hall Wheelock, the Scribner editor with whom I was corresponding, had submitted parts of it for publication in Scribner's Magazine, then under the editorship of Alfred Dashiell. Wheelock, distinguished poet as well as editor, in writing to me, showed the finest kind of literary and human sensitivity and discrimination.

Soon after arriving in New York for the year at Columbia, I called on Wheelock at his office. Our acquaintance grew into friendship, and through Wheelock I met Max Perkins, the Senior Editor at Scribner's, and Tom Wolfe, by that time an important Scribner author.

Wheelock, tall, gentle and soft-spoken, was the soul of courtesy and consideration. I had long been familiar with his poetry. Perkins, a former newspaper man, wore his hat in the office; it was always tilted backward at an abrupt angle. He had a bland and blond surface over a somewhat steely New England core. He was wise, warm, and sympathetic. He had ice-blue eyes, a finely-chiselled face, and sensitive, aristocratic hands. Wolfe resembled an exuberant black bear, a young bear, inquisitive and friendly and frolicsome. When I first met him he was restless, very shy, utterly sincere, and vulnerable, unsure of himself, for his second big novel, Of Timeand the River, had not yet been published; he was still a one-book writer. As I recall, Wolfe was then working with Perkins after hours at the Scribner office, editing the vast manuscript from which Of Time and the River was to be quarried. My attitude toward Wolfe was one of hero-worship.

Wolfe was then living in Brooklyn. I saw him a number of times during that year. He had heard that I was a poet, and apparently that meant something to him. In my copy of the first edition of LookHomeward, Angel, he wrote: "For Kimball Flaccus, from Tom Wolfe, who would have been a poet if he could, and who thinks the poet's life is the best life in the world. Good luck!"

Occasionally I joined Perkins and Wolfe for a drink at the Chatham in the cocktail hour, or lunched with Wheelock, or was invited to dine at the Perkins home, in the East 40's, where Elizabeth, one of five lovely daughters, quite captivated me. I dined with Wolfe at a Hungarian restaurant in midtown, then went with him to a Newsreel Theater in Times Square. It was a habit of his at that time to attend this theater frequently.

As I look back on that year of graduate study in New York, I recall that it was a blend of hard, formal study, such writing as I had time for, and social relaxation, which included dining out with friends such as the Perkinses or the jolly family of Olin Downes, music critic of The NewYork Times. I attended Sunday teas given by Mrs. Downes, a gracious hostess, and cocktail parties held with princely prodigality by that assiduous host to literary people, Charlie Studin. The late Irwin Edman of the Columbia Philosophy Department invited me over to his apartment for a talk and a glass of sherry. I saw writers from out of town - Witter Bynner from New Mexico, Alex Laing from Hanover, Lennox Robinson from Dublin. I saw occasional plays, attended some operas, concerts, art exhibitions.

Inevitably I was attracted to the literary and social life of New York as a kind of supplement to or relief from my formal studies. Enthused as I was about the forthcoming publication of my first book, which had been scheduled to appear the following autumn, I was undoubtedly then more interested in creative writing than in scholarship.

In a mood of rebellion, I wrote a letter to the editor of the Saturday Review ofLiterature urging that more attention be given to contemporary American Literature. It duly appeared; and I sent a clipping of it to Tom, who replied as follows under date of February 22, 1934:

Thanks very much for your letter and for the clipping from the Saturday Review. It is good of you to include my name in such a distinguished company, and I thank you for doing it. We must get together some evening soon when we are both free. Mr. Perkins enjoyed our meeting at the Hotel Chatham, and I think it would be nice if we could get together about that time. We could go to the Chatham for a drink, get him to come with us for dinner later if he can arrange it, and if he couldn't, you and I could have dinner together.

This week I am going to be pretty busy trying to finish something from which I hope to get a little badly-needed cash. Perhaps you could call me up one day next week, and then we could arrange a time for meeting.

I finished my research task and the thesis, which was approved. I passed my examinations and received the M.A. degree. In a surge of creative enthusiasm in the spring of 1934 I wrote the "Epilogue" in Avalanche of April; it was published in Scribner's Magazine under the title "Elizabeth" and was rushed to the Scribner Press just in time to be included at the end of the book.

That summer I was given the privilege of creating the typographical design of Avalanche of April. There followed the correcting of proofs, then the thrill of holding an advance copy of my first book in my hand. Max Perkins wrote to me in New Hampshire on August 23:

I am still struggling nightly with Tom Wolfe, and yet we have not far from half the book in type, and although it needs some work here and there because of the curious way in which Tom proceeded with the writing of it, it has some most magnificent writing in it. In reading this book I have almost concluded that one of the greatest things about his writing is that he gives grandeur and nobility back to man. He shows him also with all the ignobility and degradation mixed in. But the people are heroic, nevertheless. Here is old Gant, a drunkard and a bum, and yet unquestionably, as you especially see in this new book, especially at the time of his death, a truly heroic character. The trouble with these proletariat books is that they give nothing of that, and yet Tom makes you believe that it truly is there, - that there is grandeur in human character.

"The book" to which Perkins referred was Of Time and the River, which was to be published by Scribner's the following spring. It then seemed and still seems to me that Perkins in this paragraph highlighted with rare critical acumen the main source of the Wolfean magic and power - humanism, for want of a better word.

MY OWN book was published on October 5, 1934, about the time I sailed to Ireland on a travelling fellowship from Dartmouth College. My purpose was to study contemporary Irish literature, particularly the drama. On November 15, Jack Wheeiock wrote to me in Dublin:

Tom Wolfe speaks of you almost every time I see him and is always intending to write you and thank you for the copy of your book which you so kindly inscribed for him. He is very much impressed by the poems, likes them tremendously, and if he were not so busy with the details of getting his new book into shape for probable spring publication, he would have written you long ago—perhaps he has written you by now.

Under date of March 21, 1935, Jack Wheelock sent me word that at last OfTime and the River had been published, with great critical acclaim, and that Tom was en route to France:

Tom sailed for France, a few days before the publication of "Of Time and the River." We have seldom published a book that has had such a reception, with full front-page reviews in the Times, Herald-Tribune, SaturdayReview of Literature, and others, on the day of publication. It is now in its fifth printing, although not yet two weeks old, and we are bombarded by letters of an almost religious fervor, not only from readers but from booksellers and reviewers. I was fortunate in finding an odd copy of the first edition for you, and sent it forward yesterday, at the $3.00 price.

Perkins and Wheelock did not know the details of the Wolfe itinerary. On April 24, Wheelock wrote:

Tom left early in March for Europe, and has been in London and Paris. He is now, as far as I know, in Germany or Russia, and plans to return to this country early in May, so that I fear it's too late to look him up. The only address that he gave us in London was care of the American Express Company, and I suppose it's possible he may return to London for a day or so before he sails.

My own year in Europe turned out to be something of a wanderjahre, for in addition to acting in some plays at the Gate Theater, in Dublin, I travelled to England, where I saw A. E. Housman, T. S. Eliot, Charles Morgan, and A. E. (George Russell), and went also to France, Italy, and Spain. By May 1935 I was back in Dublin, about to leave on a motor trip to the west coast of Ireland. Perkins wrote me on May 10:

Thanks ever so much for writing. I was mighty glad to hear about you. It must have been a mighty fine year. I hope before you get this you may have encountered Tom somewhere. He is wandering around Europe himself, though he should have returned by now to work on his next book. He has had a very fine success indeed, and I believe he will have an equal one in England.

After Of Time and the River was published, Wolfe was attacked on the ground that his work was formless and verbose. As Wolfe wrote in a famous letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald, it is easier to be a taker-outer, that is, a refiner and polisher, than a putter-inner, that is, a creator. He, Wolfe, went on record in that letter as a putterinner, and proud of it.

In my opinion the most appealing aspects of Wolfe are his sincerity, lucidity, and humanism. For all his repetition and wordiness, Wolfe was never obscure, never insincere, always compassionate. His writing has the quality of heightened speech, in which the speaker loves words, loves the person addressed, loves life itself, and has such a consciousness of the passing moment, of time, indeed of mortality, that he stammers, reiterates, embroiders, retracts, changes and renews his utterance in a desperate effort to communicate, to be understood. There is in Wolfe none of the tendency which appears in so many literary men and women today to draw behind a veil of fancy verbal manipulation and psychological shadow-boxing. Wolfe shouted and whispered and crooned while certain of his literary contemporaries were merely grunting and tossing off wisecracks. Like D. H. Lawrence, Wolfe said yea to life when his detractors were busy saying nay in a nagging chorus. Wolfe loved America; what matter if at times he stammered or became incoherent in the expression of that love? Not for Tom Wolfe the hot-house atmosphere of the ivory tower, or the hectic double-talk of the Marxian proselytisers.

The letter which Tom had long intended to write thanking me for the inscribed copy of Avalanche of April finally came to me in the form of an inscription covering both endpapers of his volume of stories, From Death to Morning, published in 1935. Dated December 5, 1935, it is presented here in full:

DEAR KIMBALL:

I have been very very late in saying this - but will you excuse it on grounds of travel, activity, and general procrastination? - and let me say it now - I am happy to inscribe this book to so fine a poet as you are - and just as I believe and have faith that if there is anything good in a book - as I hope and believe there may be in this one, one which has been panned by the critics - that good is indestructible — so am I also certain that a book with such genuine poetry as yours can not be obliterated by fools who attacked you on the grounds that there was nothing in your book about the steelworkers in Pittsburgh. It may amuse you to know that one critic writing of one of the scenes in this book which describes the movement of negro troops through a pier said - "Yes, negroes are here - but where are Booker T. Washington, Joe Louis, and W. T. Dußose" - which reminds me that I also failed to say anything about Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and the Queen of Sheba -

Regards as always, TOM WOLFE

In this letter, Wolfe showed how generous he could be in praise of younger writers. Needless to say I was tremendously pleased and encouraged by his praise of my work. His From Death to Morning and my Avalanche of April, published a year apart, had both been attacked by Left Wing critics, although both books had favorable reviews as well. But the fact remains that books of a non-Leftist nature published during the "Red Decade" of 1930-40 had to run the gauntlet of certain hostile, prejudiced reviewers who used their positions of critical vantage for purposes of propaganda. Tom summed them up as "fools" but they were an alert and unscrupulous gang, as were the Leftists in other areas of the literary world, including Broadway and Hollywood. Many of them have since recanted and have supposedly been washed and absolved of their sins.

THE last time I saw Tom was on September 26, 1936. We met by accident on the train from Grand Central Station to New Caanan, Connecticut, where Elizabeth Perkins was to be married that day to the artist, Douglas Gorsline. Tom and I had a chat, in the course of which he told me that he was suffering from severe headaches and insomnia. He looked very tired and drawn, almost tormented. My own heavy schedule of full-time teaching plus graduate work kept me for several years from seeing as much of my friends, including Tom, as I wanted to, and he, of course, was laboring under a bone-breaking writing schedule, as was his habit.

On June 8, 1937, I sent him a letter saying that I had enjoyed reading a piece about him in The New Yorker, and he replied as follows:

DEAR KIMBALL:

Thanks very much for your letter. I am glad you liked the piece in the New Yorker.

No, I haven't moved yet, but I am going South for the summer in a few weeks. I have rented a cabin on top of a hill near home in western North Carolina. It is very beautiful country and my estate, which includes fifteen or twenty acres of land, only costs thirty dollars a month.

Yes, I am still turning it out in large bundles and I plan to take a big manuscript with me this summer. I have another big book in the process of articulation - not articulate enough yet, however, to see print.

It is good to hear that you sold a poem to Scribner's. I sold a story to the Saturday Evening Post which may not contribute much to glory, but adds a very welcome replenishment to a bank account that needs it.

I wish you all good luck. I hope that some day we shall have another book of poems from you.

Meanwhile, with all good wishes to you all, I am,

Sincerely yours, TOM WOLFE

It was evidently with very pleasant anticipation that Tom looked forward to returning to his native state, if only for a few summer months. His admission that

his current manuscript was not yet articulate enough to see print is an indication that he was indeed critical of and discriminating about his own work. And this terribly busy man had the graciousness to express the hope that I, a young and relatively unknown poet, might someday publish another book of poems.

Thomas Wolfe died on die morning of September 15, 1938, at Johns Hopkins Hospirtal in Baltimore, of complicating infections following an illness which had begun in Vancouver, British Columbia, in July. He was heading north, perhaps to Alaska, "the Big Land," when he became ill. I was staying at Tamworth, New Hampshire, when I read in a Boston newspaper on September 16 that he had died. That day I wrote an elegy entitled "Letter to Thomas Wolfe," in which my feelings of loss and grief were expressed. Wolfe had been a good friend to me, and his liking for and belief in my work had given me great encouragement. My last letter to him, the poem mentioned above, was never stamped and addressed and carried through the mails. Who knows whether he has received it or not?

But it reached and continues to reach young people; it was first published in Scholastic magazine, and published again in my second volume of poetry, TheWhite Stranger, in 1940.

As I write this I am teaching at Greensboro College in the Piedmont Plateau region of North Carolina. Some of my students, mountain born, come from the high country around Asheville. They tell me that Wolfe is now lovingly memorialized in his native town where he was once hated and reviled. Other students, perhaps from the coastal region of the state, or from the Piedmont, say they have not heard of Wolfe. But all are now curious. They ask me to tell them about this writer, for they heard that I was acquainted with him. So I drop the discussion of Herman Melville in my course in American Literature, and try to convey to these students something of Wolfe, the man, his physical size, his curiosity, his restlessness, the vast scope of his vision of America. I tell them the important thing is what he wrote. They are impressed; they are interested. They want to know more about this Southern writer who finally is becoming accepted and valued in the South. I tell them that Jonathan Daniels has written a piece in his Raleigh, North Carolina, newspaper recently, accusing the state of having shamefully neglected its greatest writer in the five or six years of his fame, while he was still alive, and pointing out that Wolfe never received an honorary degree from North Carolina or any other college or university.

I tell ray students that Wolfe thus far has found his way into only a few textbooks including the one we are using, but their sons and daughters will have him in Freshman English as sure as they are going to be born, for he was one of the great, zestful, robust, lyrical interpreters of American life in the 20th century.

Thomas Wolfe

A major literary event this fall was the publication of The Letters ofThomas Wolfe by Scribner's. For Kimball Flaccus '33, one of Dartmouth's best known men of letters, this volume has recalled his years of friendship with Wolfe; and in the article printed here he writes of the undergraduate years at Dartmouth and the post-graduate year in New York that led to their meeting. Included in the article are three hitherto unpublished letters from and one inscription by Thomas Wolfe, which appear by permission of Edward C. Aswell, Administrator C.T.A. of the estate of Thomas Wolfe. Excerpts from letters from the late Maxwell E. Perkins and from John Hall Wheelock appear by permission of Charles Scribner's Sons.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

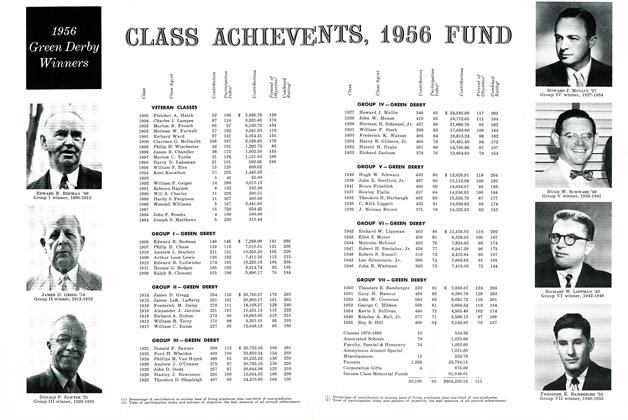

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVENTS, 1956 FUND

December 1956 -

Feature

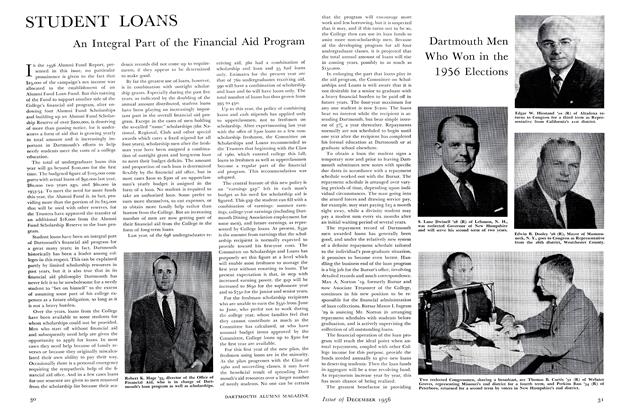

FeatureSTUDENT LOANS

December 1956 -

Feature

FeatureTHE 1956 ALUMNI FUND

December 1956 By William G. Morton '28 -

Feature

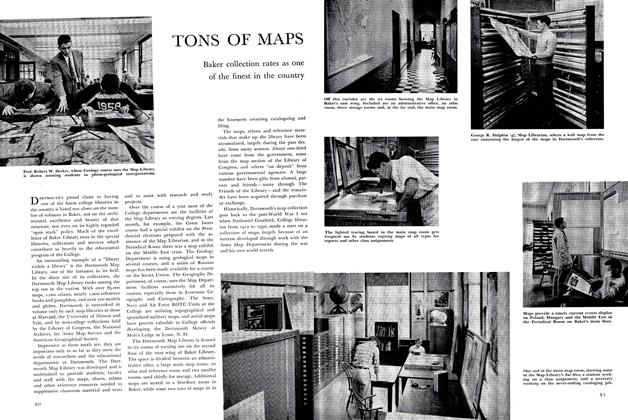

FeatureTONS OF MAPS

December 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

December 1956 By RICHARD C. CAHN, LT. (JG) EDWARD F. BOYLE, RICHARD CALKINS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1946

December 1956 By THOMAS H. GILLAUGH, ANDREW J. MURTHA

KIMBALL FLACCUS '33

-

Article

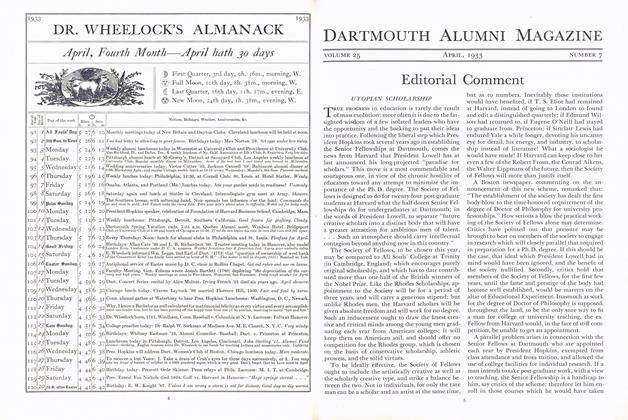

ArticleUTOPIAN SCHOLARSHIP

April 1933 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Article

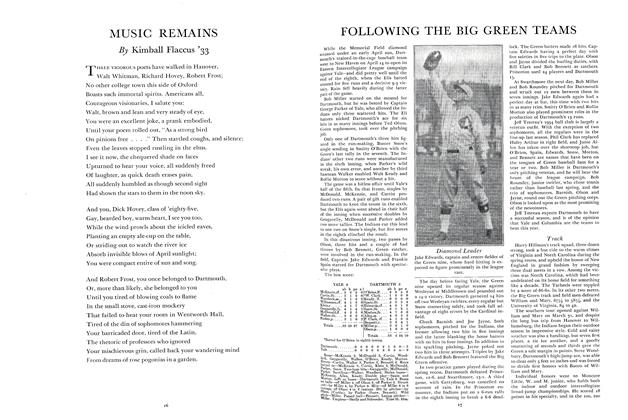

ArticleMUSIC REMAINS

May 1934 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Article

ArticleBlind Man's Buff

August 1946 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Article

ArticleThree Aleutian Love Poems

November 1946 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Feature

FeatureTHREE POEMS

January 1958 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Article

ArticleTwo Poems of England, Long Ago

NOVEMBER 1970 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWHY a Hopkins Center at Dartmouth?

October 1961 -

Feature

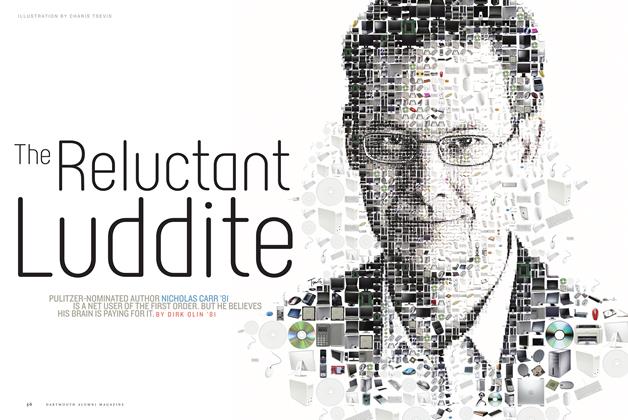

FeatureThe Reluctant Luddite

Sept/Oct 2011 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Vote

MARCH 1995 By Nancy Elliott '43A -

Feature

FeatureThe Dictionary's Function

May 1962 By PHILIP B. GOVE '22 -

Feature

FeatureScotching the Myth About Alumni Sons

MAY 1967 By RAYMOND SOBEL, M.D. -

Feature

FeatureMurder on Wheels

June 1992 By Valerie Frankel '87